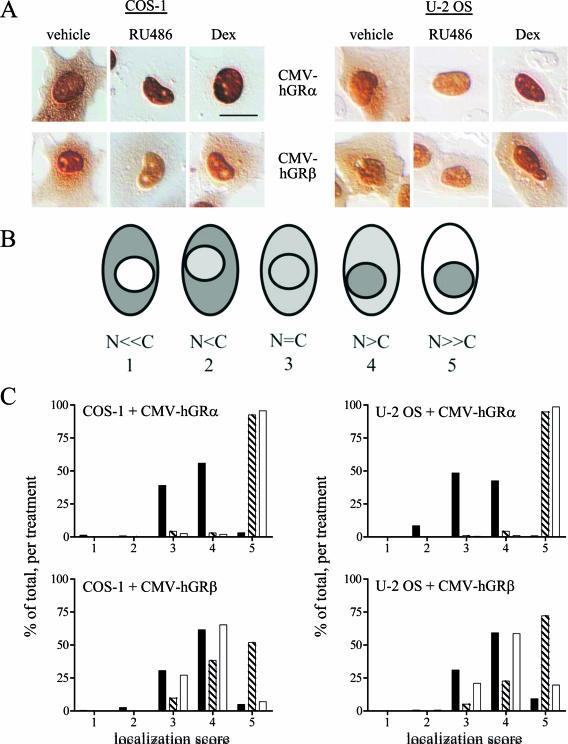

FIG. 2.

Wild-type hGRβ translocates into the nucleus in response to RU-486. (A) COS-1 (left) and U-2 OS (right) cells were transiently transfected with CMV-hGRα or CMV-hGRβ plasmids, which express wild-type hGRα or hGRβ, respectively, and treated with ethanol vehicle or 1 μM RU-486 or dexamethasone (Dex) for 3 h before being processed for immunocytochemistry with the GR#57 antibody, which recognizes both hGRα and hGRβ. (B) Schematic illustration of the scoring system used to quantitate the localization of the receptors with different treatments. A number value was assigned to each cell based on the relative amount of cytoplasmic and nuclear receptor as indicated (N, nuclear receptor; C, cytoplasmic receptor): N ≪ C, 1; N < C, 2; N = C, 3; N > C, 4; N ≫ C, 5. (C) Frequency histograms of the resulting localization scores are plotted (n ≥ 130). Black bars indicate receptor localization with vehicle treatment; striped bars indicate 1 μM RU-486; white bars indicate 1 μM dexamethasone. Both ligands caused statistically significant changes in the frequency histogram of hGRα, reflecting its nuclear translocation: the percentage of cells scored as 5 is higher for the RU-486 and dexamethasone treatments than for the vehicle treatment, while there are more vehicle-treated cells scoring at 4 or below. In contrast, only RU-486 caused nuclear translocation of hGRβ: there was little difference in the number of vehicle-treated cells versus dexamethasone-treated cells at any score, while the number of RU-486-treated cells with a score of 5 was greater than the number of vehicle-treated cells with that score. Bars, 25 μm.