Abstract

In the hippocampus, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) regulates a number of synaptic components. Among these are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing α7 subunits (α7-nAChRs), which are interesting because of their relative abundance in the hippocampus and their high relative calcium permeability. We show here that BDNF elevates surface and intracellular pools of α7-nAChRs on cultured hippocampal neurons and that glutamatergic activity is both necessary and sufficient for the effect. Blocking transmission through NMDA receptors with APV blocked the BDNF effect; increasing spontaneous excitatory activity with the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline replicated the BDNF effect. BDNF antibodies blocked the BDNF-mediated increase but not the bicuculline one, consistent with enhanced glutamatergic activity acting downstream from BDNF. Increased α7-nAChR clusters were most prominent on interneuron subtypes known to innervate directly excitatory neurons. The results suggest that BDNF, acting through glutamatergic transmission, can modulate hippocampal output in part by controlling α7-nAChR levels.

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was first described as a component that regulates development of neuronal structure and function both in the peripheral and central nervous systems (Thoenen et al., 1987; Thoenen, 1995; Lewin and Barde, 1996; Cohen-Cory and Lom, 2004). Subsequently it became clear that BDNF also has acute effects at the synapse, serving as an activity-dependent regulator of synaptic plasticity and participating rapidly in synaptic transmission (Schinder and Poo, 2000; Poo, 2001; Blum et al., 2002; Kovalchuk et al., 2004; Bramham and Messaoudi, 2005). Developmentally, BDNF has numerous synaptic actions including maturation of GABAergic signaling and stabilization of newly formed synapses (Huang et al., 1999; Alsina et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2002; Bramham and Messaoudi, 2005). Many of these effects have been demonstrated in the hippocampus where BDNF is released from both the dendrites and axons of pyramidal neurons (Haubensak et al., 1998; Hartmann et al., 2001; Balkowiec and Katz, 2002).

BDNF can regulate the level of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) containing α7 subunits in the hippocampus and other systems (Kawai et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2004). These α7-nAChRs are expressed at relatively high levels on interneurons in early postnatal hippocampus (Jones and Yakel, 1997; Zhang et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2001; Adams et al., 2002; Kawai et al., 2002). Due to the high calcium permeability of α7-nAChRs (Bertrand et al., 1993; Seguela et al., 1993), they can both depolarize the cell and influence a variety of calcium-dependent events (Broide and Leslie, 1999; Berg and Conroy, 2002). As a result, the distribution and regulation of these receptors can profoundly impact network function.

Here we examine the effects of BDNF on dissociated rat hippocampal neurons in culture and show that BDNF increases both surface and internal pools of α7-nAChRs. The BDNF-mediated increases are dependent on glutamatergic activity and are confined to distinct neuronal subtypes. Glutamatergic neurons show no α7-nAChR increase with BDNF treatment. Within GABAergic neurons, those showing the greatest increases are interneurons that directly innervate pyramidal neurons. The results suggest that BDNF acts through glutamatergic signaling to selectively elevate α7-nAChRs on interneurons positioned to inhibit glutamatergic cells.

Results

BDNF Up-Regulates Both Surface and Internal α7-nAChRs

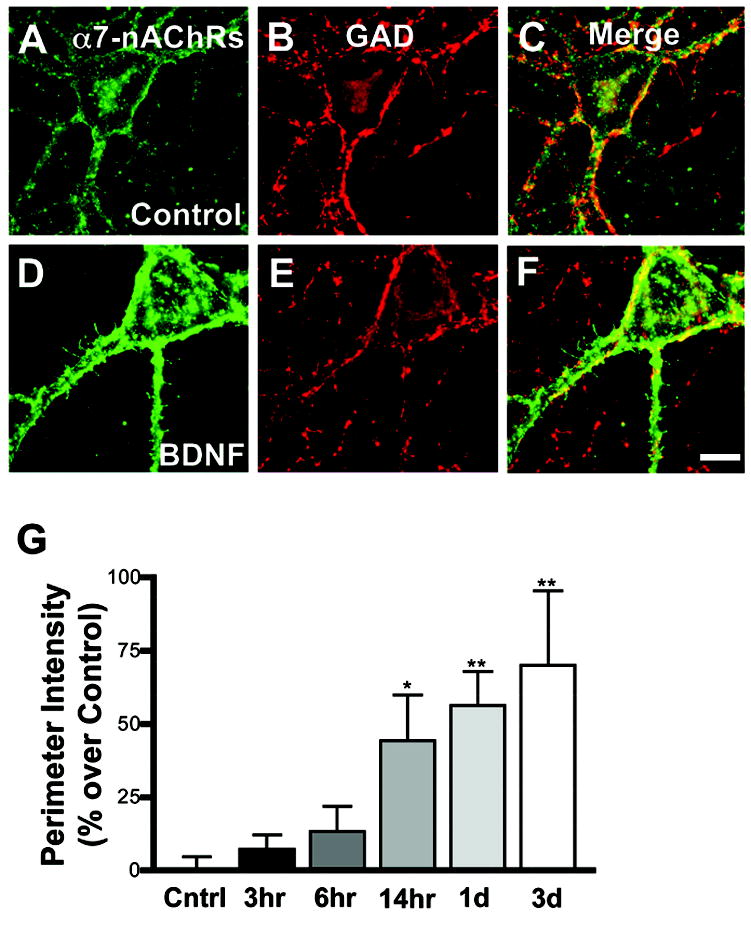

Clusters of α7-nAChRs are prominent on the soma and dendrites of hippocampal interneurons in culture. This was found by labeling intact cells with Alexa488-α-bungarotoxin (Alexa-αBgt) to reveal surface clusters of α7-nAChRs (Fig. 1A,D). Cells were then rinsed, fixed, and immunostained with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase 65/67 (GAD) to identify GABAergic interneurons (Fig. 1B,E). About 60% of the GAD-positive cell bodies had significant levels of α7-nAChR staining. Previous studies showed that Alexa-αBgt staining under these conditions co-distributes with surface staining by an antibody against α7-nAChRs (Kawai et al., 2002). Additionally, pre-incubating neurons with an excess of methyllycaconitine (MLA), a specific antagonist of α7-nAChRs, blocked the Alexa-αBgt staining, providing additional evidence for specificity. In comparison to control cells (Fig.1A-C), 24 hour treatment with BDNF (Fig.1D-F) led to a significant increase in surface expression of α7-nAChRs without significantly changing the number of stained cells. The results were normalized to the mean signal obtained for untreated GABAergic neurons in the same experiments, thereby compensating for the differences in baseline levels among experiments. The increase was first evident after 14 hours of BDNF treatment. Longer treatments led to slightly greater effects (Fig. 1F). In all subsequent experiments, cells were treated with BDNF for 16 or 24 hours, as indicated.

Figure 1.

Time dependence of α7-nAChR increases by BDNF. Dissociated hippocampal cells were treated with control media (A–C) or with 50 ng/mL BDNF (D–F) for 24 hours and then stained with Alexa-αBgt for α7-nAChRs (A,D), fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized, and co-stained for GAD (B, E), and the paired images merged (C, F). Cells were treated with BDNF for the indicated times (G), and the relative staining levels were quantified. Values for individual neurons were normalized to mean control values in each experiment; net increases over control are shown. A 14 hour exposure to BDNF produced a significant increase in α7-nAChR staining. Results were compared using ANOVA with the Dunnett post hoc test. Scale bar: 10 μm. Asterisk, p < 0.05; double asterisk, p < 0.01.

The time-dependence of the BDNF effect was consistent with de novo receptor synthesis and trafficking to the cell surface. Treating the cells with brefeldin-A (BFA) prior to and during a 16 hour exposure to BDNF to block transport from the Golgi completely blocked the BDNF-induced increase in surface α7-nAChR staining. No decrement was seen in controls treated with BFA, indicating that little basal turnover of receptor occurs during the test period (Fig. 2A). BFA does block nicotine-induced endocytosis and exocytosis of α7-nAChR (Liu et al., 2005). The effects of long-term BFA treatment on BDNF-treated cells, however, may be complex: while short-term treatments with BFA do not affect synaptic release at mature synapses (Zakharenko et. al, 1999), long-term exposure may interfere. Experiments with blockers of transcription and protein synthesis were also problematical over this time span because of toxic effects. This motivated us to test whether internal pools of α7-nAChRs could be identified and determine how they were affected by the BDNF treatment. Internal α7-nAChRs were visualized by first treating intact cells with Alexa-αBgt to label surface receptors (Fig. 2B,E), and then rinsing, lightly fixing and permeabilizing with methanol, and labeling intracellular receptors with rhodamine (rho)-αBgt (Fig. 2C,F). Prominent clusters of intracellular α7-nAChRs could be identified in this manner, sometimes lying immediately beneath surface clusters of the receptors (Fig. 2D,G). The staining is likely to represent fully assembled receptors because only the pentameric α7-nAChRs are thought to bind significant amounts of αBgt (Anand et al., 1993). Including MLA with the rho-αBgt eliminated the internal clusters. In comparison to controls (Fig. 2B-D), 24-hour treatment with BDNF (Fig. 2E-G) significantly increased the dendritic area occupied by intracellular pools of α7-nAChRs (Fig. 2H). The results show that BDNF increases both surface and internal α7-nAChR pools, consistent with net receptor accumulation occurring either through increased synthesis or stabilization.

Figure 2.

BDNF effects on internal α7-nAChR pools and dependence on vesicle trafficking. Treating cells with 10 μg/mL BFA, which prevents trafficking of proteins from the Golgi, completely blocked the ability of BDNF (50 ng/mL for 16 hours) to increase surface levels of α7-nAChRs (A). Results were compared using ANOVA with the Bonferonni post-hoc test for selected pairs of means. Internal pools of α7-nAChRs were visualized by first staining intact cells with Alexa-αBgt to label surface receptors (B,E) and then fixing in methanol and labeling internal receptors with rho-αBgt (C,F). Individual dendrites are shown lined with α7-nAChR clusters on the surface and containing internal clusters as well (D,G). Comparing control cells (B–D) and cells treated with BDNF for 24 hours (E–G) showed that the latter had undergone a significant increase in the percentage of dendritic area that was occupied by internal clusters of receptors (H). Results were compared using a Student’s two-tailed t-test. Scale bar: 10 μm. Asterisk, p < 0.05; double asterisk, p < 0.01.

BDNF Depends on Glutamatergic Signaling

BDNF, acting through TrkB receptors, can exert effects directly on a target cell or indirectly through changes in synaptic or electrical activity (Li et al., 1998; Kafitz et al., 1999; Schumann, 1999; Blum et al., 2002; Matsumoto et al., 2006). Immunostaining reveals that essentially all hippocampal neurons in culture have substantial amounts of both surface and internal TrkB receptors (data not shown). A known pathway of BDNF action involves TrkB receptor activation of Nav1.9 sodium channels to depolarize the cell (Kafitz et al., 1999; Blum et al., 2002). It is unlikely, however, that this depolarization drives the effects seen on hippocampal α7-nAChR expression. Overnight treatment with saxitoxin (10 nM), which blocks a subset of voltage-gated sodium channels that include Nav1.9, depressed α7-nAChR levels but was unable to prevent the BDNF-induced increase in surface receptors (surface staining in arbitrary units: 19 ± 2 for saxitoxin vs. 26 ± 1 for saxitoxin plus BDNF; mean ± SEM, n = 3).

BDNF can also modulate glutamatergic transmission, potentiating release of glutamate presynaptically and regulating postsynaptic receptor function as well (Levine et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998; Levine and Kolb, 2000). Blocking NMDA receptors with 50 μM 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV) prevented the BDNF-mediated increase in α7-nAChR staining without affecting basal levels of α7-nAChRs over the same time period (Fig. 3A). The results suggested that BDNF may exert its effects on α7-nAChR levels by acting through glutamatergic transmission. To test this, we treated cultures with 20 μM bicuculline for 24 hours to block inhibitory transmission through GABAA receptors; this protocol increases spontaneous excitatory activity in the cultures (Arnold et al., 2005). The excitation is likely to be confined to glutamatergic pathways since the hippocampus in thought to lack endogenous cholinergic neurons. Bicuculline mimicked BDNF in increasing α7-nAChR staining, and it was not additive with BDNF (Fig. 3B). The results are consistent with a mechanism in which NMDA receptors act downstream of BDNF. Supporting this view, we found that treating cultures with anti-BDNF antibodies prevented BDNF-mediated increases but was unable to prevent the bicuculline-induced increases in α7-nAChR levels (Fig. 3B). The results show that bicuculline can up-regulate α7-nAChR levels without requiring BDNF. The simplest interpretation is that BDNF increases α7-nAChR levels by increasing glutamatergic activity.

Figure 3.

Dependence of BDNF effect on glutamatergic signaling. Hippocampal cells in culture were treated with BDNF (50 ng/mL), APV (50 μM), or a combination of the two. Surface staining for α7-nAChRs was quantified (A). APV did not change basal levels of α7-nAChR staining, but it completely prevented the increase seen with BDNF. Bicuculline (20 μM), used to block GABAergic inhibition and thereby increase glutamatergic excitation in the cultures, mimicked the BDNF effect but was not additive with it (B). Functional antibodies against BDNF (Abs) prevented the increase seen with BDNF alone but did not prevent the increase seen with bicuculline. The results are consistent with glutamatergic signaling acting downstream of BDNF to elevate α7-nAChR levels. Results were compared using ANOVA with the Bonferonni post hoc test for selected pairs of means. Asterisk, p < 0.05; double asterisk, p < 0.01.

BDNF Distinguishes Subsets of Interneurons

The fact that not all GAD-positive hippocampal neurons showed increased α7-nAChR staining in response to BDNF suggested that the effect might be specific for distinct interneuron subtypes. The hippocampus contains multiple classes of interneurons with different functions; immunostaining for neuropeptides provides a means of distinguishing among the classes (Freund and Buzsaki, 1996; Soltesz, 2006). Somatostatin-positive (SS) hippocampal cells include HIPP cells in the dentate gyrus and OL-M cells in the CA regions, both of which directly innervate glutamatergic neurons and mediate feedback inhibition (Katona et al., 1999). Estrogen receptor β (ER-β) is an early marker for parvalbumin-positive fast-spiking basket cells that innervate glutamatergic cells (Buzsaki and Freund, 1996; Blurton-Jones and Tuszynski, 2002). Most vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-positive hippocampal cells represent interneurons that selectively innervate other interneurons (Ascady et al., 1996a,b; Hajos et al., 1996). SS-, parvalbumin-, and VIP-positive cells form three major non-overlapping populations of neurons in the hippocampus. Though it was not possible to stain for parvalbumin in these young cultures, it is likely that ER-β cells form a representative subpopulation of these neurons.

Co-staining hippocampal cultures for surface α7-nAChRs and either SS, ER-β, or VIP demonstrated the heterogeneity in responses to 24 hours of BDNF treatment. When normalized to mean values across untreated GABAergic neurons, those cells expressing SS had low levels of surface α7-nAChRs and underwent a substantial increase in response to BDNF (Fig. 4). BDNF treatment also increased the moderate levels of surface α7-nAChRs on neurons defined by ER-β. In contrast, BDNF had no effect on neurons expressing VIP. The distribution of neurons among the GABAergic subpopulations was unchanged by BDNF treatment (43 ± 8% SS-positive, 7 ± 2% were VIP-positive, and 32 ± 9% were ER-β positive). GAD-negative neurons were presumed to be glutamatergic cells and formed a distinct population. They displayed low levels of surface α7-nAChRs and showed no increase in response to BDNF treatment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Identification of interneuronal subtypes that display BDNF-mediated increases in surface α7-nAChRs. Hippocampal cultures were treated with BDNF (50 ng/mL) for 24 hours, then stained with Alexa-αBgt, fixed in 4% PFA, permeabilized, and stained for either SS, ER-β as an early marker of parvalbumin positive interneurons, or VIP, and co-stained for GAD. GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons were distinguished by the presence and absence, respectively, of somatic GAD staining. BDNF treatment significantly increased surface staining for Alexa-αBgt on SS-positive and ER-β-positive neurons. BDNF had no effect on VIP-positive cells or on glutamatergic (GLU) cells. BDNF did not alter the percentage of GABAergic cells that were positive for SS, VIP, or ER-β. Surface fluorescence was normalized to the mean fluorescence signal across untreated GABAergic neurons (dashed line). The effect of BDNF on each subpopulation was compared by Student’s two-tailed t-test. Asterisk, p < 0.05; triple asterisk, p < 0.001.

SS and VIP neurons responded to BDNF in different manners and were investigated further. BDNF effects on internal α7-nAChR pools mimicked those seen for surface receptors across neuronal cell type. This was shown by using a modified procedure which preserved immunostaining for neuropeptides while also visualizing intracellular α7-nAChRs. Cells were first incubated with unlabeled αBgt to block surface α7-nAChRs and then were lightly fixed with 2% PFA and permeabilized. A second incubation included primary antibodies for SS and VIP along with Alexa-αBgt for intracellular α7-nAChRs. The fixation reduced the intensity of Alexa-αBgt staining but still enabled internal α7-nAChR clusters to be seen. Few GAD-negative neurons had detectable α7-nAChR clusters, and BDNF treatment did not increase the number of such cells (Fig. 5). In contrast, many GAD-positive neurons displayed intracellular α7-nAChR clusters, and the proportion nearly doubled following BDNF treatment. Only a small fraction of SS-containing neurons displayed the intracellular clusters, but BDNF again increased the proportion significantly. As seen for surface α7-nAChR labeling, a substantial proportion of VIP-expressing neurons contained internal α7-nAChR clusters, but the proportion was not changed by BDNF treatment. The results show that BDNF exerts largely the same effects on internal α7-nAChR pools as it does on surface receptors, and that the same subsets of neurons respond.

Figure 5.

BDNF effects on internal pools of α7-nAChRs within neuronal cell types. After blocking surface α7-nAChRs with unlabeled αBgt, hippocampal cultures were lightly fixed in 2% PFA and incubated with Alexa-αBgt to label intracellular pools of α7-nAChRs. Cells having one or more internal clusters were scored as positive. The percentage of cells having at least one internal α7-nAChR cluster was quantified for each condition. As seen for surface expression of α7-nAChRs, SS-positive cells showed an increase, while VIP-positive and glutamatergic cells did not. Individual categories of cells were compared to vehicle using Student’s two-tailed t-test. Asterisk, p < 0.05.

Discussion

We show here that BDNF up-regulates α7-nAChR levels on specific subpopulations of hippocampal neurons in culture and that the up-regulation applies both to surface and intracellular receptor pools. The BDNF effect requires glutamatergic transmission and apparently acts through it to achieve the up-regulation. Most interestingly, the up-regulation occurs on interneuron subtypes that directly innervate excitatory neurons in the hippocampus and, at least in part, provide feedback inhibition. Other types of hippocampal neurons do not up-regulate α7-nAChRs in response to BDNF even though they express TrkB receptors. These include excitatory neurons, which express low levels of α7-nAChRs, and interneurons that innervate other interneurons, many of which express high levels of α7-nAChRs. The results suggest that BDNF, acting through glutamatergic regulation of α7-nAChRs, specifically affects hippocampal excitability.

The imaging of α7-nAChRs achieved here with Alexa-αBgt was specific for α7-nAChRs since it was blocked by 5 μM MLA. This antagonist excludes the possibility that the toxin sites include GABAA receptors with β3 subunit; such GABA receptors have a lower affinity for αBgt and a different pharmacology (McCann et al., 2006). The fact that a long exposure to BDNF was required for detectable increases in α7-nAChR staining suggests that it relied on de novo synthesis of receptors. Blockers of protein synthesis could not be tested because they were toxic over this time period. The inference that de novo synthesis was required, however, was consistent both with the ability of BFA to block the increase and the finding that surface and intracellular pools increased in parallel. BDNF has previously been shown to elevate α7-nAChR levels on chick ciliary ganglion neurons by de novo synthesis (Zhou et al., 2004). Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that the increased receptor staining reflected, in part, lateral migration of previously dispersed receptors to generate readily visible receptor clusters. Measuring total α7-nAChR levels in the cultures was not informative because BDNF-responsive populations represented a small fraction of the total cells expressing α7-nAChRs.

The BDNF-induced increases in α7-nAChR levels required activation of NMDA receptors. The simplest model accounting for these results is that BDNF increases glutamatergic activity and this, in turn, mediates α7-nAChR expression and accumulation. The effects of glutamate could not be tested directly because extended exposure proved toxic. However, other methods provided strong support of the model. First, blocking NMDA receptors with APV prevented the BDNF effect, indicating that transmission through NMDA receptors was necessary. Second, bicuculline treatment, known to increase excitatory activity in the cultures, mimicked the BDNF effect but was not additive with it. This is consistent with an increase in glutamatergic activity causing an increase in surface receptor expression. These treatments did not alter α7-nAChR basal levels, though longer treatments can do so (Kawai et al., 2002). The bicuculline effect was not seen previously because only a narrow range of α7-nAChR staining was examined and the analysis was less quantitative (Kawai et al., 2002). Lastly, though the BDNF-mediated increase in surface α7-nAChRs could be prevented with function-blocking BDNF antibodies, these antibodies had no effect on the bicuculline-driven increase. Taken together, the results suggest that glutamatergic activity can act independently from BDNF to increase α7-nAChR levels. This places glutamatergic transmission downstream from BDNF activity in the regulatory pathway.

Glutamatergic neurons in the hippocampus release BDNF from both dendritic and axonal locations (Haubensak et al., 1998; Hartmann et. al, 2001; Balkowiec and Katz, 2002), and this, in turn, can enhance glutamatergic transmission both pre- and postsynaptically (Levine et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998; Levine and Kolb, 2000). Most hippocampal neurons in culture receive glutamatergic input and have surface TrkB receptors, as is true in vivo (Yan et al, 1997; Drake et al., 1999). Accordingly, BDNF enhancement of glutamatergic transmission, whether presynaptic or postsynaptic in mechanism, could apply broadly across the neuronal population but does not. The fact that only certain interneuronal subtypes display increased α7-nAChR levels in response to BDNF strongly suggests the existence of cell-type-specific regulatory mechanisms engaged by the increased input.

Interestingly, interneurons that increase their α7-nAChR levels in response to BDNF are predominantly those thought to innervate glutamatergic neurons. Anatomical and electrophysiological studies show that both SS-positive neurons and parvalbumin-positive neurons (as identified by ER-β staining) inhibit pyramidal cells and act to decrease activity in the hippocampus. In contrast, VIP neurons do not elevate α7-nAChR levels in response to BDNF, and many VIP neurons selectively inhibit other interneurons. Increased activity in these cells would produce disinhibition of the hippocampus (Katona et al., 1998; reviewed in Freund and Buzsaki, 1996 and Soltesz 2006).

BDNF-induced up-regulation of α7-nAChRs may be designed to support hippocampal homeostasis. Release of BDNF from glutamatergic neurons, perhaps triggered by periods of elevated activity, will increase α7-nAChRs on interneurons inhibiting hippocampal glutamatergic neurons. Since α7-nAChRs are excitatory, increased levels of the receptors should enhance firing of the interneurons, thereby increasing inhibition of the downstream glutamatergic neurons. Activation of the receptors would arise from the diverse cholinergic projections to the hippocampus provided by the septum (Freund and Buzsaki, 1996). In addition to excitatory effects, α7-nAChRs can act in other ways to influence hippocampal function. Since α7-nAChRs have a high relative calcium permeability (Bertrand et al., 1993; Seguela et al., 1993), they can modulate neuronal function through regulation of calcium-dependent processes, including changes in gene expression. Activation of α7-nAChRs has been shown to stabilize cholinergic synapses on hippocampal interneurons in culture (Zago et al., 2006). Thus BDNF may effect specific subpopulations of hippocampal neurons by enhancing excitability, altering gene expression, or increasing the probability of receiving cholinergic innervation. The outcome could alter the balance of excitation and inhibition in the hippocampus, as well as contributing to network properties such as rhythm generation. The overall effects on spike timing and hippocampal network activity will depend on the precise functional connectivity and synaptic properties of the interneuron subpopulations involved.

Experimental Methods

Cell Cultures

Hippocampal cultures were prepared from 18- to 19-day-old Sprague Dawley rat embryos as previously described (Kawai et. al, 2002). Briefly, hippocampi were removed rapidly under stereomicroscopic observation, cut into small pieces, and digested with 20 U/ml of trypsin (Invitrogen; Gaithsburg, MD) in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Invitrogen) at 37°C for 12 minutes. The tissue segments were then transferred to Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) with 10% heat inactivated horse serum (Invitrogen), triturated with a fire-polished pasteur pipette and plated at 4 x 104 cells per 12 mm glass coverslip previously coated with poly-D-lysine (>300 kDa; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Subsequent feeding occurred twice weekly, each time replacing half the volume with fresh Neurobasal media with 2% B-27 (Invitrogen). On day 6, some cultures received 5 μM cytosine-D-arabinofuranoside to inhibit further proliferation of non-neuronal cells. The cultures were maintained in a humidified tissue culture incubator with 5% CO2 until use. Where indicated, the following compounds were applied to the cells during the last day in culture: 50 ng/ml BDNF (recombinant BDNF; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), 10 nM saxitoxin, 50 μM APV, 20 μM bicuculline, and 10 μg/mL chicken anti BDNF polyclonal antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI).

Fluorescent Labeling of α7-nAChRs

Surface α7-nAChRs were labeled by incubating 20-day-old cultures of dissociated hippocampal cells with 100 nM Alexa-αBgt (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for one hour at 37°C (Kawai et al., 2002). Cells were then washed in Neurobasal medium and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and processed for fluorescent immunocytochemistry. Two methods were used to label internal α7-nAChRs. Some cells were stained for surface α7-nAChRs as above, then fixed and lightly permeabilized in 95% methanol at −20°C for 10 minutes. Cells were washed in room temperature PBS and then incubated with 100 nM rho-αBgt to reveal internal clusters. A different method was used when needing to preserve intracellular epitopes for identifying neuronal subtypes. In these cases, surface α7-nAChRs were blocked with unlabelled 100 nM αBgt for one hour at 37°C and then washed and lightly fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 minutes. After washing again in PBS, cells were incubated with primary antibodies and 100 nM Alexa-αBgt to label intracellular pools of receptors, and then processed for fluorescent immunocytochemistry. Nonspecific binding was routinely assessed by including 5 μM MLA in the incubation with the Alexa-αBgt, but equivalent blockade was also obtained with 50 nM MLA. Co-staining with a goat anti-α7-nAChR antiserum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) yielded co-distribution with Alexa-αBgt, providing additional confirmation of specificity.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 2% PFA followed by 4% PFA, each for 10 minutes, and then washed again in PBS and stained. Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% Triton X-100 plus 5% normal donkey serum in PBS and incubated with the cells for one hour at 37°C. These included a mouse anti-GAD monoclonal antibody (1:500–1:1000; MAB351; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), a rabbit anti-GAD polyclonal antibody (1:1000; Chemicon), a mouse anti-VIP polyclonal antibody (1:500; Immunostar, Hudson, WI), a rabbit anti-SS polyclonal antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a rabbit anti-ER-β polyclonal antibody (1:250; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and a rabbit anti-TrkB polyclonal antibody (1:100; TrkB (H-181); Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After labeling, the cells were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with appropriate secondary antibodies raised in donkey and conjugated to Cy3, FITC, Cy5, or Alexa-647 fluorophores (1:200–1:500 dilution in 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum in PBS; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). The cells were then washed three more times in PBS and mounted using anti-fade mounting solution (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Image Acquisition and Quantification

Digital images of fluorescently labeled cells were collected using a CCD camera mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert (63x oil-immersion objective, 1.4 numerical aperture lens) and equipped with SlideBook deconvolving software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Santa Monica, CA). GABAergic cells were identified by eye based on GAD-positive fluorescence present in the cell body but absent from the nucleus. Ten to twenty GABAergic neurons were imaged per coverslip. Neurons in relative isolation were chosen to facilitate quantification of fluorescence along the dendrites. Controls in which one or more primary antibodies were omitted showed no significant cross-contamination among fluorescence channels. Images were collected in z-stacks of 11 focal planes separated by 0.5 μm. SlideBook was used to deconvolve the images and to quantify surface intensity of α7-nAChRs. For each image, one edge of at least two neurites was masked and the mean pixel intensity under the mask was calculated. In some cases, data were normalized to the mean of control GABAergic cells on an independent coverslip. Each separate culture was counted as a single experiment (n) for statistical purposes. To exclude unhealthy cultures, experiments were discarded if control cultures lacked visibly detectable staining for α7-nAChRs or if BDNF-treated cultures showed no visibly detectable increase in α7-nAChR staining.

For measurements of internal α7-nAChRs, a 2-D projection image was generated to visualize clusters in all planes. Control cultures in each experiment were used to set the display ranges to be measured. Maximum intensities were calculated for individual cells by averaging the intensity of the brightest clusters (4 per neuron) across four neurons per experiment. Minimum intensities were set to the mean non-cellular background across four control images. These ranges were applied to all experiments for a given culture. Measurements of cluster size, area, and number were performed using ImagePro 3.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Clusters were defined as having at least nine contiguous pixels (0.9 μm2) with at least 50% maximal intensity, and were counted along dendritic segments. The total area of dendrites measured per cell was recorded and used to calculate the percent area occupied by internal α7-nAChR pools. The same procedure was used to analyze the percentage of cells expressing internal clusters.

Statistics

Values represent the mean ± SEM of results from 3–14 experiments. Statistical differences between two means were determined using the two-tailed Student's t test; comparisons among more than two were determined by ANOVA. The Dunnett post-hoc test was used to compare experimental means to a control mean, and the Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to compare selected pairs of means.

Materials

Unless otherwise indicated, all drugs and compounds were purchased from Sigma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiao-Yun Wang for expert technical assistance and Honey B Tijerina for assistance with preliminary data analysis. Support was provided by NIH grants NS12601 and NS35469, and by a grant from Phillip Morris, USA Inc & International. K.A.M. and W.M.Z. are Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program Predoctoral and Postdoctoral Fellows, respectively.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acsady L, Arabadzisz D, Freund TF. Correlated morphological and neurochemical features identify different subsets of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive interneurons in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1996a;73:299–315. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acsady L, Gorcs TJ, Freund TF. Different populations of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive interneurons are specialized to control pyramidal cells or interneurons in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1996b;73:317–334. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CE, Broide RS, Chen Y, Winzer-Serham UH, Henderson TA, Leslie FM, Freedman R. Development of the α7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat hippocampal formation. Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsina B, Vu T, Cohen-Cory S. Visualizing synapse formation in arborizing optic axons in vivo: dynamics and modulation by BDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/nn735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Peng X, Lindstrom J. Homomeric and native alpha 7 acetylcholine receptors exhibit remarkably similar but non-identical pharmacological properties, suggesting that the native receptor is a heteromeric protein complex. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:241–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80177-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold FJ, Hofmann F, Bengtson CP, Wittmann M, Vanhoutte P, Bading H. Microelectrode array recordings of cultured hippocampal networks reveal a simple model for transcription and protein synthesis-dependent plasticity. J Physiol. 2005;564:3–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkowiec A, Katz DM. Cellular mechanisms regulating activity-dependent release of native brain-derived neurotrophic factor from hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10399–10407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DK, Conroy WG. Nicotinic α7 receptors: synaptic options and down-stream signaling in neurons. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:512–523. doi: 10.1002/neu.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Galzi JL, Devillers-Thiery A, Bertrand S, Changeux JP. Mutations at two distinct sites within the channel domain M2 alter calcium permeability of neuronal α7 nicotinic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1993;90:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum R, Kafitz KW, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin-evoked depolarization requires the sodium channel Na(V)1.9. Nature. 2002;419:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nature01085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, Tuszynski MH. Estrogen receptor-beta colocalizes extensively with parvalbumin-labeled inhibitory neurons in the cortex, amygdala, basal forebrain, and hippocampal formation of intact and ovariectomized adult rats. J Comp Neurol. 2002;452:276–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broide RS, Leslie FM. The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in neuronal plasticity. Molec Neurobiol. 1999;20:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02741361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR, Messaoudi E. BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: the synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Milner TA, Patterson SL. Ultrastructural localization of full-length trkB immunoreactivity in rat hippocampus suggests multiple roles in modulating activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8009–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08009.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cory S, Lom B. Neurotrophic regulation of retinal ganglion cell synaptic connectivity: from axons and dendrites to synapses. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:947–956. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041883sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Acsady L, Freund TF. Target selectivity and neurochemical characteristics of VIP-immunoreactive interneurons in the rat dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Heumann R, Lessmann V. Synaptic secretion of BDNF after high-frequency stimulation of glutamatergic synapses. EMBO J. 2001;20:5887–597. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubensak W, Narz F, Heumann R, Lessmann V. BDNF-GFP containing secretory granules are localized in the vicinity of synaptic junctions of cultured cortical neurons. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1483–1493. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.11.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Kirkwood A, Pizzorusso T, Porciatti V, Morales B, Bear MF, Maffei L, Tonegawa S. BDNF regulates the maturation of inhibition and the critical period of plasticity in mouse visual cortex. Cell. 1999;98:739–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Yakel JL. Functional nicotinic ACh receptors on interneurones in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;504:603–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.603bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Rose CR, Thoenen H, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin-evoked rapid excitation through TrkB receptors. Nature. 1999;401:918–921. doi: 10.1038/44847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H, Zago W, Berg DK. Nicotinic α7 receptor clusters on hippocampal GABAergic neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and neurotrophins. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7903–7912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07903.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Acsady L, Freund TF. Postsynaptic targets of somatostatin-immunoreactive interneurons in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1999;88:37–55. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk Y, Holthoff K, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin action on a rapid timescale. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ES, Crozier RA, Black IB, Plummer MR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates hippocampal synaptic transmission by increasing N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10235–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ES, Kolb JE. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor increases activity of NR2B-containing N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in excised patches from hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:357–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001101)62:3<357::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin GR, Barde YA. Physiology of the neurotrophins. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:289–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YX, Zhang Y, Lester HA, Schuman EM, Davidson N. Enhancement of neurotransmitter release induced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10231–10240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ford B, Mann MA, Fischbach GD. Neuregulins increase α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and enhance excitatory synaptic transmission in GABAergic interneurons of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5660–5669. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05660.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Tearle AW, Nai Q, Berg DK. Rapid activity-driven SNARE-dependent trafficking of nicotinic receptors on somatic spines. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1159–1168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3953-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Numakawa T, Yokomaku D, Adachi N, Yamagishi S, Numakawa Y, Kunugi H, Taguchi T. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced potentiation of glutamate and GABA release: different dependency on signaling pathways and neuronal activity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann CM, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH, Sanes JR. The cholinergic antagonist alpha-bungarotoxin also binds and blocks a subset of GABA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2006;103:5149–5154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600847103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo M-m. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Neurosci Rev. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain α7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder AF, Poo M-m. The neurotrophin hypothesis for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:639–645. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01672-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman EM. Neurotrophin regulation of synaptic transmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I. Diversity in the neuronal machine. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thoenen H, Barde YA, Davies AM, Johnson JE. Neurotrophic factors and neuronal death. Ciba Found Symp. 1987;126:82–95. doi: 10.1002/9780470513422.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and neuronal plasticity. Science. 1995;270:593–598. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada MK, Nakanishi K, Ohba S, Nakamura T, Ikegaya Y, Nishiyama N, Matsuki N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes the maturation of GABAergic mechanisms in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7580–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07580.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan A, Radeke MJ, Matheson CR, Talvenheimo J, Welcher AA, Feinstein SC. Immunocytochemical Localization of TrkB in the Central Nervous System of the Adult Rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:135–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zago WM, Massey KA, Berg DK. Nicotinic activity stabilizes convergence of nicotinic and GABAergic synapses on filopodia of hippocampal interneurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko S, Chang S, O'Donoghue M, Popov SV. Neurotransmitter secretion along growing nerve processes: comparison with synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:507–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Liu C, Miao H, Gong ZH, Nordberg A. Postnatal changes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 2, alpha 3, alpha 4, alpha 7 and beta 2 subunits genes expression in rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1998;16:507–18. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Nai Q, Chen M, Dittus JD, Howard MJ, Margiotta JF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and trkB signaling in parasympathetic neurons: relevance to regulating α7-containing nicotinic receptors and synaptic function. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4340–4350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0055-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]