Abstract

Background.

New developments have made 16-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) a promising technique for detecting significant coronary stenoses. At present, there is a paucity of data on the relation between fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement and MDCT stenosis detection.

Objective.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relation between the anatomical severity of coronary artery disease detected by MDCT and functional severity measured by fractional flow reserve (FFR).

Methods.

We studied 53 patients (39 men and 14 women, age 62.5±8.1 years) with single-vessel disease scheduled for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). All patients underwent MDCT scanning one day prior to PCI and FFR was measured before PCI in the target vessel.

Results.

MDCT analysis could be performed in 52 of 53 patients (98.1%) and all patients had adequate FFR and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) measurements. The mean stenosis diameters calculated by MDCT and QCA were 67.0±11.6% and 60.8±11.6% respectively. No significant relation was found between MDCT and QCA (r=0.22, p=0.12) The mean FFR in all patients was 0.67±0.18. A relation of r=-0.46 (p=0.0006) between QCA and FFR was found. In contrast, no relation between MDCT and FFR could be demonstrated (r=–0.09, p=0.50). Furthermore, a high incidence of false-positive and false-negative findings was present in both diagnostic modalities.

Conclusion.

There is no clear relation between the anatomical and functional severity of coronary artery disease as defined by MDCT and FFR. Therefore, functional assessment of coronary artery disease remains mandatory for clinical decisionmaking. (Neth Heart J 2007;15:5-11.)

Keywords: coronary arteriosclerosis, coronary artery disease, tomography (computed), fractional flow reserve

Since the introduction of coronary angiography, various methods have been introduced to assess the severity of stenosis in coronary arteries. The most simple and frequently used method is visual estimation of the percentage of stenosis. However, the aforementioned method has limited value for precise determination of coronary stenoses. Visual estimation overestimates stenoses prior to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and underestimates post-PCI stenoses.1,2 To improve clinical assessment of anatomical lesion characteristics, quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) was introduced to calculate the dimensions of the stenotic segment more precisely.3 Nevertheless, the severity of coronary stenoses calculated by QCA does not always correlate with the clinical presentation of related symptoms.4-7 In 1996, fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement was introduced to evaluate the clinical significance of a stenosis by comparing the pressure before the stenosis with pressure after the stenosis during maximal coronary hyperaemia induced by adenosine.8 FFR measurement has become an indispensable tool for decision-making in patients with coronary artery disease.8-10

Recently, multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) was introduced as a noninvasive technique to visualise coronary artery disease. MDCT has been proven to be capable of detecting significant coronary stenoses in patients with stable sinus rhythm.11-14 In addition, in a post-mortem ex-vivo set-up MDCT images correlated well with histopathological findings regarding fatty, fibrous or calcified plaque components. In contrast, conventional catheter-based coronary angiography does not provide more in-depth information on the vessel wall composition.15

Although coronary MDCT is a promising diagnostic tool to evaluate coronary artery disease, its correlation with FFR has not yet been investigated. Therefore, its role as a diagnostic tool for clinical decision-making in coronary interventions is still uncertain. The aim of this study was to compare coronary stenosis assessment by MDCT with functional stenosis severity by FFR.

Methods

Patient selection

In this prospective study, we studied 53 patients with no previously documented coronary artery disease, stable angina and single-vessel disease on diagnostic coronary angiography, who were scheduled for PCI. Clinical data and diagnostic coronary angiograms from referring hospitals were discussed by a team of interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to decide on the most optimal treatment strategy for each individual patient. All patients with evidence of myocardial ischaemia (objectified by a stress exercise test) and only one coronary stenosis who were scheduled for elective PCI were considered for inclusion. Patients with previous PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting, irregular heart rate (no sinus rhythm or frequent extrasystoles), haemodynamic instability (cardiogenic shock or clinical evidence of heart failure), pregnancy, severe overweight (>125 kg), renal failure (creatinine >115) and known allergy to iodine contrast media were excluded. In addition, patients had to be able to hold their breath for 15 seconds for adequate 16-slice MDCT scanning. Final inclusion depended on location of the target lesion and suitability for FFR measurement (no tortuositas >90° and no chronic total occlusions). Patients were scanned by MDCT one day prior to the scheduled PCI. Patients with a heart rate >70 beats/ min received additional oral β-blockers one hour prior to scanning to improve image quality. Before PCI, FFR was measured in the target vessel. This study was approved by the institutional review committee and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

MDCT data acquisition

Scans were performed on a 16-slice multidetector computed tomography system (Somatom Sensation 16, Siemens AG, Forchheim, Germany). All scans were made in the cranio-caudal direction with patients in supine position. The procedure started with bolus timing with the region of interest placed in the ascending aorta. Subsequently, a short thoracic scan was performed, ranging from the carina approximately 4 cm downwards. The upper level of the coronary arteries was determined in this scan to reduce cardiac scan time. An expiratory breathhold, ECG-gated cardiac scan was started 0.5 cm above the upper coronary level. Scanning was carried out with a 12 x 0.75 mm collimation, 420 ms gantry rotation time and 2.8 mm table feed per gantry rotation. Iodixanol 270 mg/ml (Visipaque 270, Amersham Health, UK) was used as contrast agent, 20 ml in the test bolus and 120 ml in the cardiac scan. The contrast agent was followed by a saline bolus chaser in both scans. Contrast and saline bolus chaser were injected through a 20G venflon, placed in a cubital vein, with a flow rate of 5 ml/s.16

MDCT data reconstruction

Data were reconstructed with windows starting at an absolute time before the R peak. The start of a reconstruction window was based on the best out of 21 reconstructions (0 to 1000 ms before the R peak in steps of 50 ms) of an axial slice in the mid-portion of the coronary artery. Up to three reconstructions were made, based on the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD), circumflex (LCX) and right coronary artery (RCA). The reconstructed slice thickness was 1 mm with an increment of 0.5 mm.

MDCT data evaluation

MDCT data were evaluated by two experienced observers (JD and TPW), who met in consensus using dedicated post-processing software (Vitrea 2, Vital Images, Plymouth, MN, USA). The observers were blinded to the angiography and FFR results. MDCT image quality was evaluated and scored as 1 (excellent), 2 (good), 3 (fair), 4 (poor) or 5 (unevaluable) using a previously described method.16 To compare angiography and MDCT results, the segment classification of the American Heart Association was used.17 Of all target lesions, severity, length and composition were noted. After initial visual lesion assessment by both observers simultaneously, stenoses were objectively quantified using Vitrea 2 analysis software (Vitrea 2, Vital Images, Plymouth, MN, USA). This quantification was performed in axial or multiplanar reformation (MPR) images. Minimal lumen diameter in the stenosis and vessel lumen diameter just proximal to the stenosis were measured. Diameter stenosis was subsequently calculated by dividing minimal lumen diameter through the reference lumen diameter. A diameter reduction of ≥50% was defined as a significant stenosis. In the analysis of calcified plaques, the stenoses were divided into two groups: calcified lesions (with a ratio of 50% or more) and mildly/ noncalcified lesions (with a ratio of less than 50%).

FFR measurements

Intracoronary nitrates (400 μg in 2 ml) were given at the start of the procedure. To assess the fractional flow reserve, a 0.014 inch pressure guidewire (Radi Medical System, Upsala, Sweden) was used to measure the pressure just distal to the stenosis during a period of maximal hyperaemia induced by intravenous adenosine infusion (140 μg /kg/minute).8 Aortic pressure was measured through the guiding catheter (6 French). FFR was calculated as the ratio of the coronary pressure distal to the lesion measured by the pressure wire to the mean aortic pressure measured by the guiding catheter.8 Measurements were performed twice and the FFR for this study was calculated as the average of both measurements. An FFR <0.75 was considered to be functionally significant.8,9

Quantitative coronary angiography

Before PCI, two orthogonal projections of coronary angiography were obtained. After selection of the optimal projection using CMS (Medis Co., Nuenen), QCA was performed in both projections by a previously described and validated automatic contour detection technique (Quantcor QCA, PMI-Siemens, Maastricht, the Netherlands). All stenoses were evaluated from both orthogonal projections and reported as the mean of the data from both projections.3 Off-line QCA was performed by an independent analyst, not aware of other patient data, to measure the percentage of the stenosis and the minimal lumen diameter (mm) before PCI. A stenosis of 50% or more was considered to be significant.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± 1 standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. The relation between anatomical severity (MDCT and QCA) and functional severity (FFR) of coronary artery disease was evaluated regarding FFR as the reference. The relation between QCA and FFR was tested using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Because the degree of stenosis measured by MDCT was not normally distributed, Spearman’s rank correlation was used in the comparison between the degrees of stenosis measured by QCA and MDCT and the comparison between MDCT and FFR. In the evaluation of the two calcification groups, the independent samples ttest was used to compare continuous data and the Fisher’s exact test was used to test categorical data. All tests were two-sided and a p value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Correlation and Bland-Altman analysis was performed using MedCalc (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). All other calculations were performed using SPSS version 11.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

A total of 53 patients (39 men and 14 women, mean age 62.5±8.1 years) with 53 de novo lesions were included in the study and scheduled for PCI. All patients could be scanned one day prior to PCI. The MDCT scan of one of the 53 patients could not be analysed due to motion artefacts, leaving 52 patients for the final analysis. The mean of the quality scores of the scans was 2.1±1.0. Patient characteristics are summarised in table 1. Mean heart rate during MDCT scanning was 60.0±12.8 beats/min. Of the 52 target lesions, 4 (7.7%) were visually judged to have a nonsignificant (<50%) stenosis and 48 lesions (92.3%) had a significant (≥50%) stenosis on MDCT. The mean percentage of stenosis calculated by MDCT was 67.0±11.6%. There was disagreement between visual and quantitative analysis in three stenoses: two stenoses were visually interpreted as significant, but not significant by quantification, and one stenosis was significant by quantification but not on visual assessment.

Table 1.

Patient and lesion characteristics.

| Characteristics | n=52 |

|---|---|

| Women, n (%) | 13 (25.0) |

| Age (years) | 62.5±8.2 |

| Angina, n (%) | |

| - Class 1 | 2 (3.8) |

| - Class 2 | 22 (42.3) |

| - Class 3 | 26 (50.0) |

| - Class 4 | 2 (3.8) |

| Calcification lesion, n (%) | |

| - Severe calcification | 16 (30.8) |

| - Mild/no calcification | 36 (69.2) |

| Vessel of target lesion, n (%) | |

| - LAD | 25 (48.1) |

| - LCX | 11 (21.2) |

| - RCA | 16 (30.7) |

LAD=left anterior descending coronary artery, LCX=left circumflex coronary artery, RCA=right coronary artery.

In all included patients, an FFR measurement could be obtained before the PCI was performed. The mean FFR was 0.67±0.18, ranging from 0.17 to 0.97. Thirtyfive patients (67.3%) had a functionally significant stenosis (FFR <0.75) whereas 17 (32.7%) patients had a nonsignificant coronary pressure ratio (FFR ≥0.75).

QCA analysis was adequately performed in all patients. The mean percentage of stenosis measured by QCA was 60.8±11.6%. Thirteen lesions (25.0%) were not found to be significant on QCA, although ten of these lesions were judged to be significant on MDCT.

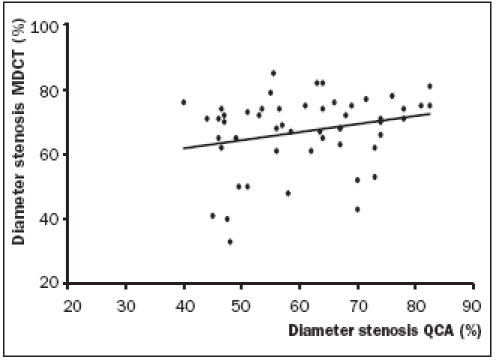

Figure 1 shows the correlation between MDCT and QCA in our study group. There was a weak, although not significant, correlation of r=0.22 (p=0.12, CI = –0.06 to 0.47) found between MDCT and QCA, using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Figure 1.

Correlation between diameter stenosis measurements by 16-slice multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) (r=0.22, CI -0.06 to 0.47, p=0.12).

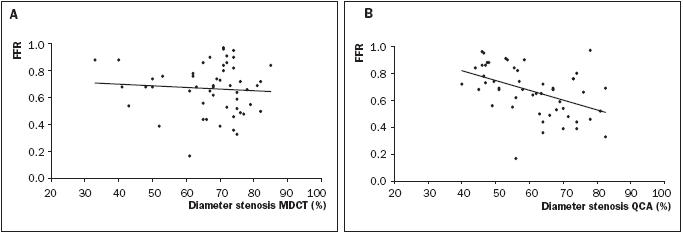

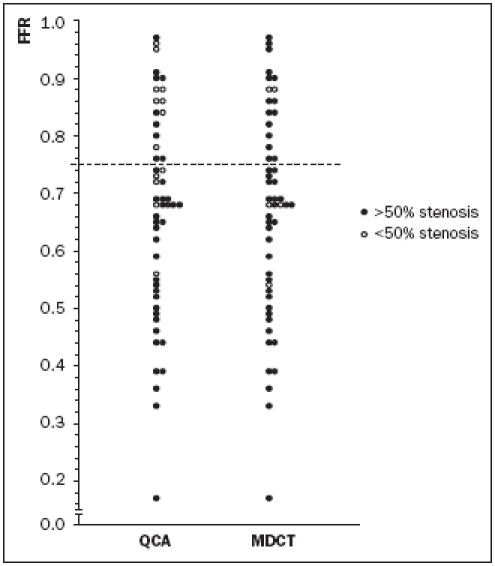

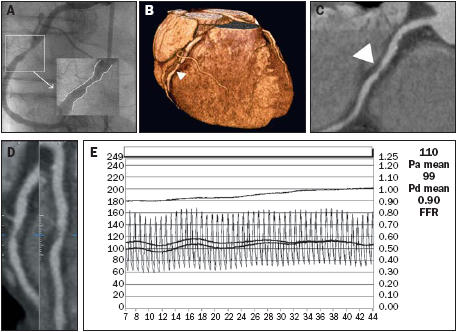

The correlations between MDCT and FFR, and QCA and FFR are shown in figure 2. When comparing FFR and QCA data, a positive correlation of r=-0.46 (p=0.0006, CI=-0.65 to -0.22) was found. There were five false-negative (QCA <50% and a FFR <0.75) and nine false-positive (QCA ≥50% and FFR ≥0.75) findings. The correlation between FFR and MDCT was not significant (r=-0.09, p=0.50, CI =-0.36 to 0.19) with three false-negative (MDCT <50% and FFR <0.75) and 15 false-positive (MDCT ≥50% and FFR >0.75) findings. Figure 3 shows the functional FFR plotted against the two anatomical tests. An example of the discrepancy between FFR and MDCT or QCA findings is illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 2.

Correlation between (A) 16-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and fractional flow reserve (FFR) (r=-0.09, CI=-0.36 to 0.19, p=0.50) and between (B) quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) and FFR (r=-0.46, CI=-0.65 to -0.22, p=0.0006).

Figure 3.

Relation between fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurements and results of 16-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) analysis. Each dot represents outcome of one anatomical test in relation to FFR in a single patient. The dashed line represents the FFR cut-off value of 0.75.

Figure 4.

Example of mismatch between anatomical and functional severity of a stenosis in a patient with an FFR >0.75. (A) A significant stenosis of the right coronary artery (RCA) was seen on diagnostic coronary angiography and the stenosis calculated by QCA was 54%. (B) Three-dimensional reconstruction by MDCT with volume rendering in the same patient. View from anterior reveals the stenosis in the RCA (arrow). (C) Close-up multiplanar reformation image of the proximal RCA reveals a soft plaque (arrow). MDCT segment analysis (D) shows a significant stenosis of 74% (calculated) in the proximal RCA. (E) Despite these anatomical changes in the vessel, an FFR of 0.90 ([Pressure distal of the stenosis (Pd mean) in mmHg] / [Aortic pressure (Pa mean) in mmHg]=99/110=0.90) was found, indicating that the stenosis was not functionally significant.

When comparing calcified lesions with mild/noncalcified lesions on MDCT, no differences were found in FFR, diameter stenosis by MDCT, reference diameter by QCA, diameter stenosis by QCA and falsepositive or false-negative findings (table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome in lesions with mild/no calcification and severe calcification.

| Mild/no calcification (n=36) | Severe calcification (n=16) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFR | 0.68±0.17 | 0.64±0.21 | 0.43 |

| Stenosis by MDCT | 66.7±11.6 | 67.8±12.0 | 0.77 |

| Reference diameter by QCA (mm) | 2.66±0.56 | 2.65±0.63 | 0.93 |

| Diameter stenosis by QCA (%) | 61.1±11.1 | 60.5±12.9 | 0.88 |

| False-positive, n (%) | 10 (27.8) | 5 (31.2) | 1.0 |

| False-negative, n (%) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (12.5) | 0.22 |

False positive=stenosis on MDCT >50% and on FFR >0.75, false-negative=stenosis on MDCT <50% and on FFR <0.75, FFR=fractional flow reserve, MDCT=multidetector computed tomography, QCA=quantitative coronary angiography.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that the assessment of coronary stenoses by MDCT does not correlate with the functional significance of coronary artery disease measured by FFR. At present, QCA is the most frequently used method to assess coronary stenoses. Recently, MDCT has also been shown to be a reliable diagnostic technique for evaluation of coronary artery stenoses.11-14 However, it is known that anatomical coronary artery disease such as assessed by conventional angiography does not always correlate with the functional severity of the disease.4-7

Conventional coronary angiography and functional assessment of coronary artery disease

Eyeball estimation of coronary stenoses during conventional coronary angiography is most frequently used for clinical decision-making in daily practice. However, this method has been shown to be unreliable, even when performed by experienced interventional cardiologists.18 Bartunek et al. found that the diagnostic accuracy of QCA in predicting fractional flow reserve <0.72 was high and clinical decisionmaking in individual patients was allowed.19 In our study we found a similar correlation between QCA and FFR with a higher degree of stenosis in patients with lower FFRs. The DEFER study investigated the use of FFR as a tool to identify which patients would benefit from PCI.9,10 It was shown that stable patients with a coronary artery stenosis and documented myocardial ischaemia can be safely deferred from angioplasty when FFR cut-off values are implemented. Our study supports the clinical conception that functional coronary measurements are crucial, as no clear relation between coronary anatomy and function could be found.

MDCT in evaluating coronary stenoses

Various studies on 16-slice MDCT have shown that MDCT is promising for the detection of coronary stenoses.11-14 However, spatial and temporal resolutions still limit the possibilities of this technique to differentiate between various degrees of stenoses. Furthermore, coronary calcification influences image quality, and blurring due to severe calcification can cause an image to be uninterpretable.16,20-22 For these reasons, the ability to accurately quantify stenoses with 16-slice MDCT remains limited. Furthermore, MDCT tends to overestimate the degree of stenosis compared with conventional angiography.11,12 This phenomenon was also found in our study, as 19.2% of the lesions were not significant on QCA, but significant on quantified MDCT. However, our study focused only on diseased segments, which in part explains the high incidence of false-positive findings. Nonetheless, MDCT has some major advantages over conventional angiography. Besides visualising lumen narrowings, MDCT can provide insight into the different components of the vessel wall, such as calcifications, fibrous tissue and soft plaque. This ability was also confirmed in IVUS studies.23-25 Recently, 64-slice MDCT has been evaluated for the detection of coronary lumen narrowing.26-29 This rapid progress in the development of MDCT techniques with higher resolutions is promising and is likely to equalise the differences seen between conventional angiography and MDCT in the near future.

MDCT and functional evaluation of coronary stenoses

Although the accuracy of MDCT in evaluating coronary anatomy is improving, the relation between its anatomy assessment and coronary function remains unclear. Our study shows no relation between coronary stenoses assessment by MDCT and functional evaluation by FFR measurements. The high incidence of falsepositive and false-negative findings support the discrepant findings of coronary anatomy and coronary function described in conventional angiography. The limitations of 16-slice MDCT to correctly assess coronary stenoses by MDCT as mentioned could in part explain this discordance. Improvement of new MDCT techniques such as 64-slice MDCT and software for quantitative analysis might acquire more insight into the relation between coronary anatomy and function. However, despite these new techniques, a more precise definition of coronary anatomy will not reduce the overall rate of discrepant findings.6,8

MDCT in clinical decision-making

MDCT thus seems to be a valuable and safe first-line tool to assess coronary anatomy in patients with angina. However, its precise role within the decision process of whether or not to treat a specific lesion by revascularisation therapy is still unclear. The poor correlation and high incidence of false-positive and false-negative findings by MDCT in relation to FFR in our study group suggests that further functional lesion evaluation is mandatory after stenoses are initially diagnosed. Therefore the results from this study have significant clinical implications for the decision-making process prior to subsequent revascularisation therapy. However, our study population consisted of patients with a confirmed stenosis on the baseline coronary angiogram and objective evidence of myocardial ischaemia. More studies are needed to investigate the relation between functional tests, such as nuclear or magnetic resonance imaging techniques, and MDCT.

Study limitations

This study was performed in patients with single-vessel disease as defined by conventional coronary angiography. We do acknowledge the limitation of the inclusion criteria, as patient selection was based on visual assessment of the first angiogram, clinical patient parameters, suitability of the target vessel for FFR measurements and possibility for MDCT scanning one day prior to PCI. Also, the spatial resolution of 16-slice MDCT in our study limited adequate quantification of coronary stenosis with MDCT. However, the discordance between functional assessment and anatomical measurements by both quantified and visually assessed MDCT implicates that coronary anatomy defined by MDCT should not be used as a single argument for clinical decision-making in patients with coronary artery disease. Furthermore, we did not use routine sublingual nitrates before MDCT scanning. Systematic use of nitrates may improve image quality, especially in distal coronary arteries. It is known that in case of a heavily calcified lesion, lesion severity may be overestimated. When comparing highly calcified lesions with low- or noncalcified lesions on MDCT, no differences were found in FFR, diameter stenosis by MDCT, reference diameter by QCA, minimal lumen diameter nor diameter stenosis by QCA (table 2).

Conclusion

This study shows that anatomical lesion severity assessment by 16-slice MDCT does not correlate with the functional severity of lesions measured by FFR. Although MDCT seems to be useful as a screening tool for patients with suspected coronary artery disease, there does not yet seem to be a complementary role for MDCT in clinical decision-making for revascularisation strategies. Further studies are warranted to define the role of MDCT in daily clinical practice.

References

- 1.Fischer JJ, Samady H, McPherson JA, et al. Comparison between visual assessment and quantitative angiography versus fractional flow reserve for native coronary narrowings of moderate severity. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimball BP, Bui S, Cohen EA, Cheung PK, Lima V. Systematic bias in the reporting of angioplasty outcomes: accuracy of visual estimates of absolute lumen diameters. Can J Cardiol 1994;10: 815-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiber JH, van der Zwet PM, Koning G, et al. Accuracy and precision of quantitative digital coronary arteriography: observer-, short-, and medium-term variabilities. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1993;28:187-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topol EJ, Nissen SE. Our preoccupation with coronary luminology. The dissociation between clinical and angiographic findings in ischemic heart disease. Circulation 1995;92:2333-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zijlstra F, Fioretti P, Reiber JH, Serruys PW. Which cineangiographically assessed anatomic variable correlates best with functional measurements of stenosis severity? A comparison of quantitative analysis of the coronary cineangiogram with measured coronary flow reserve and exercise/redistribution thallium-201 scintigraphy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:686-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zijlstra F, van Ommeren J, Reiber JH, Serruys PW. Does the quantitative assessment of coronary artery dimensions predict the physiologic significance of a coronary stenosis? Circulation 1987; 75:1154-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RF, Marcus ML, White CW. Prediction of the physiologic significance of coronary arterial lesions by quantitative lesion geometry in patients with limited coronary artery disease. Circulation 1987;75:723-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Peels K, et al. Measurement of fractional flow reserve to assess the functional severity of coronary-artery stenoses. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bech GJ, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve to determine the appropriateness of angioplasty in moderate coronary stenosis: a randomized trial. Circulation 2001;103:2928-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bech GJ, De Bruyne B, Bonnier HJ, et al. Long-term follow-up after deferral of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty of intermediate stenosis on the basis of coronary pressure measurement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuettner A, Beck T, Drosch T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive coronary imaging using 16-detector slice spiral computed tomography with 188 ms temporal resolution. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollet NR, Cademartiri F, Krestin GP, et al. Improved diagnostic accuracy with 16-row multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:128-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann MH, Shi H, Schmitz BL, et al. Noninvasive coronary angiography with multislice computed tomography. JAMA 2005; 293:2471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achenbach S, Ropers D, Pohle FK, et al. Detection of coronary artery stenoses using multi-detector CT with 16 x 0.75 collimation and 375 ms rotation. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1978-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolaou K, Becker CR, Muders M, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic lesions in human ex vivo coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis 2004;174:243-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorgelo J, Willems TP, van Ooijen PM, et al. A 16-slice multidetector computed tomography protocol for evaluation of the gastroepiploic artery grafts in patients after coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1994-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation 1975;51:5-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brueren BR, ten Berg JM, Suttorp MJ, et al. How good are experienced cardiologists at predicting the hemodynamic severity of coronary stenoses when taking fractional flow reserve as the gold standard. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2002;18:73-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartunek J, Sys SU, Heyndrickx GR, Pijls NH, De Bruyne B. Quantitative coronary angiography in predicting functional significance of stenoses in an unselected patient cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:328-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kefer J, Coche E, Legros G, et al. Head-to-head comparison of three-dimensional navigator-gated magnetic resonance imaging and 16-slice computed tomography to detect coronary artery stenosis in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:92-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker CR, Knez A, Leber A, et al. Detection of coronary artery stenoses with multislice helical CT angiography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002;26:750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuettner A, Kopp AF, Schroeder S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moselewski F, Ropers D, Pohle K, et al. Comparison of measurement of cross-sectional coronary atherosclerotic plaque and vessel areas by 16-slice multidetector computed tomography versus intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:1294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caussin C, Ohanessian A, Ghostine S, et al. Characterization of vulnerable nonstenotic plaque with 16-slice computed tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol 2004;94: 99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenhagen P, Tuzcu EM, Stillman AE, et al. Non-invasive assessment of plaque morphology and remodeling in mildly stenotic coronary segments: comparison of 16-slice computed tomography and intravascular ultrasound. Coron Artery Dis 2003;14:459-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leber AW, Knez A, von Ziegler F, et al. Quantification of obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesions by 64-slice computed tomography: a comparative study with quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:147-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pugliese F, Mollet NR, Runza G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive 64-slice CT coronary angiography in patients with stable angina pectoris. Eur Radiol 2006;16:575-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mollet NR, Cademartiri F, van Mieghem CA, et al. High-resolution spiral computed tomography coronary angiography in patients referred for diagnostic conventional coronary angiography. Circulation 2005;112:2318-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leschka S, Alkadhi H, Plass A, et al. Accuracy of MSCT coronary angiography with 64-slice technology: first experience. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]