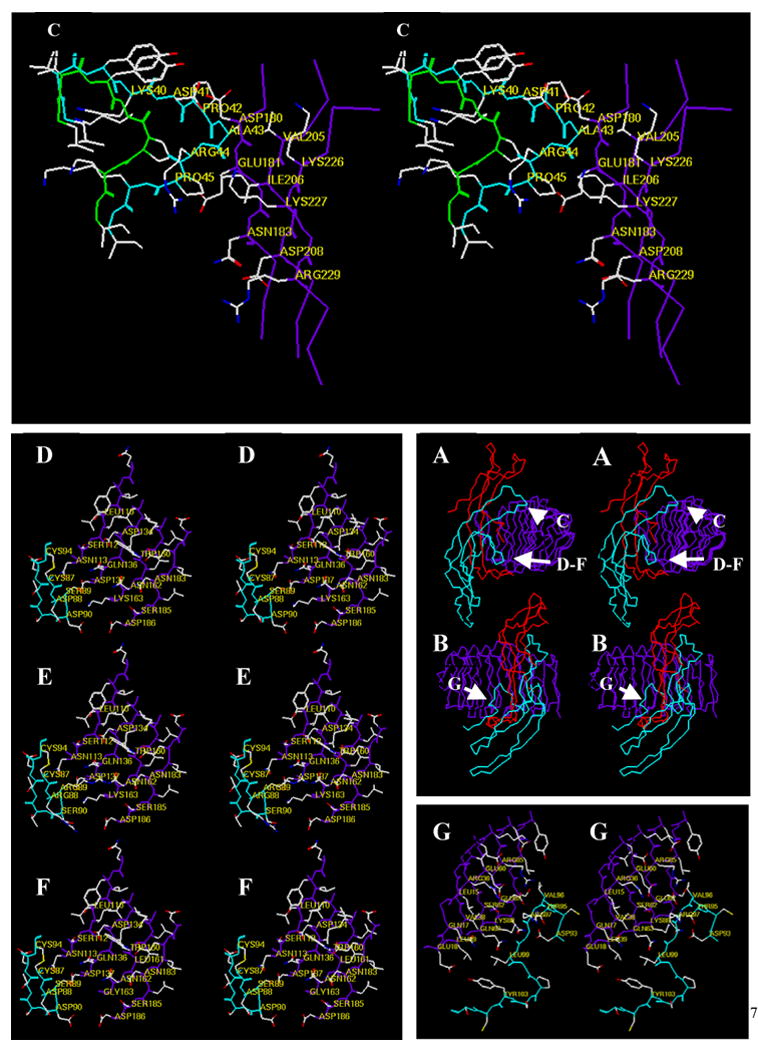

Figure 3. Contacts of the hFSH β-subunit with its FSHR fragment.

(Panels A and B, center right) Cα coordinates of the hFSH-FSHR fragment shown in relaxed stereo view. Panel A depicts the complex turned in an orientation that shows the relative positions of the enlarge regions highlighted in Panel C and in Panels D, E, and F. Panel B depicts the complex in an orientation that shows the position of the enlarged region highlighted in Panel G. Color scheme: red, α-subunit; cyan, β-subunit; purple, FSHR fragment. (Panel C) Relaxed stereo view of the tip of β-subunit loop 2 as it is found in the FSH-FSHR fragment complex (cyan backbone) and as it is modeled in the deletion mutant hFSHδ4 (green backbone). The Cα carbons of several residues in the native β-subunit and in the FSHR fragment are labeled. Those in the analog are not labeled to make the figure easier to visualize. The residues that have been deleted are: Asp41-Pro42-Ala43-Arg44. Thus, in the mutant Lys40 is joined to Pro45. Deletion of residues 41–44 was expected to eliminate contacts between the sidechains of Pro42 and Ala43 and between the backbone of Ala43 with the receptor. Note that this region of the β-subunit appears not to contribute to receptor binding specificity. (Panel D). Relaxed stereo view of the “determinant loop” (cyan backbone) and the region of the receptor that it contacts in the FSHR fragment (purple backbone). Note that this region of FSH has little or no influence on binding to cell surface FSHR. (Panel E) Replacing FSH residues Asp88, Ser89, Asp90, and unlabeled Ser91 (Panel D) with Arg-Arg-Ser-Thr, its hCG counterpart, enhances binding of FSH to LHR; the converse swap in hCG does not enhance binding of hCG to FSHR, but reduces binding of hCG to LHR. (Panel F) Replacing FSHR residues Lys163 with glycine and Lys88 (c.f. Panel G) with asparagine enables hCG to bind to FSHR, but has little influence on the binding of FSH to FSHR. Together, the findings that FSH binding to the cell surface FSHR is not reduced or improved substantially by changes in “determinant loop” residues that face this region of the receptor suggest that these contacts are either not present in the cell surface receptor or that they contribute little to FSH-FSHR interactions. (Panel G) Relaxed stereo view of residues in the region of the FSH seatbelt that controls FSH receptor binding specificity (cyan backbone) and adjacent residues of the FSHR fragment (purple backbone). It is difficult to see how contacts between these hormone and receptor residues confer ligand binding specificity. Receptor residues Lys58 (not labeled)-Glu60-Ser62-Gln63, the central receptor leucine-rich repeat that contacts this portion of the seatbelt, are identical in most mammalian FSHR and LHR. Receptor residue Lys88, which faces Asp93, a residue found at the end of the seatbelt loop in nearly all β-subunit residues can be changed to asparagine without altering FSH or LHR binding. Glu87 is a glutamine in mammalian LHR and would be expected to make similar contacts. Arg36 is serine in mammalian LHR, which would be expected to facilitate contacts with FSH residue Arg97.