Abstract

Purpose: The research sought to provide evidence to support the development of a long-term strategy for the Via Christi Regional Medical Center Libraries.

Methods: An information needs assessment was conducted in a large medical center serving approximately 5,900 physicians, clinicians, and nonclinical staff in 4 sites in 1 Midwestern city. Quantitative and qualitative data from 1,295 self-reporting surveys, 75 telephone interviews, and 2 focus groups were collected and analyzed to address 2 questions: how could the libraries best serve their patrons, given realistic limitations on time, resources, and personnel, and how could the libraries best help their institution improve patient care and outcomes?

Results: Clinicians emphasized the need for “just in time” information accessible at the point of care. Library nonusers emphasized the need to market library services and resources. Both clinical and nonclinical respondents emphasized the need for information services customized to their professional information needs, preferences, and patterns of use. Specific information needs in the organization were identified.

Discussion/Conclusions: The results of this three-part, user-centered information needs assessment were used to develop an evidence-based strategic plan. The findings confirmed the importance of promoting library services in the organization and suggested expanded, collaborative roles for hospital librarians.

Highlights

The use of multiple data collection instruments in a qualitative study provides complementary perspectives that can enhance credibility of data analysis.

Clinicians value the provision of “just in time” information services available at the point of patient care.

Implications

Librarians can use needs assessment findings to make evidence-based decisions about the allocation of key library services and resources.

Opportunities exist for hospital librarians to design and deliver sophisticated information services aimed at specific professional groups in the organization.

Collaborative work on multidisciplinary teams in the hospital offers librarians additional opportunities to share their professional expertise in meaningful ways.

INTRODUCTION

Standard 6 of the Medical Library Association's “Standards for Hospital Libraries 2002 with 2004 Revisions” [1] calls for librarians to perform ongoing assessment of the organization's knowledge-based information needs and to base planning on the results of assessment findings. Properly designed assessments of library performance assist library decision makers in evaluating the quality of provided services, as well as in allocating scarce resources most effectively [2]. Assessments that take into account the views of library users and nonusers can also guide the strategic direction of the library [3]. This paper describes the process of planning, implementing, and analyzing a formal needs assessment process to inform one library's strategic planning initiative.

BACKGROUND

Via Christi Regional Medical Center (VCRMC) in Wichita, Kansas, was created through the merger of two large acute care hospitals in 1995 and currently comprises four sites providing acute care, mental health services, and rehabilitation services. In cooperation with the Kansas University School of Medicine, the medical center now operates the second largest family practice residency training program in the United States as well as programs in general and orthopedic surgery, internal medicine, anesthesiology, psychiatry, and osteopathic medicine.

At present, the Via Christi Libraries reside on the St. Francis and St. Joseph campuses. Three full-time medical librarians, one full-time assistant librarian, and one part-time library specialist provide information services to all physicians and VCRMC employees. As the medical center has expanded, the librarians have been challenged by the need to provide information services to more people at more locations. Providing electronic access to information resources was one way of responding to this challenge. In 2003, the VCRMC librarians launched a Web page that provided access to various electronic databases, full-text online journals, and the libraries' online catalog. Access to the Website resulted in a marked increase in utilization of electronic library resources. Increases in utilization were accompanied, however, by increased costs and the simultaneous explosion of electronic information resources available on the market.

In 2004, the librarians participated in a day-long retreat to discuss challenges facing the libraries, considering the following questions:

Should changes be made in the allocation of print versus electronic resources?

What would those changes cost in relation to potential benefits?

Should the libraries adopt a marketing plan to attract potential users?

Should they explore other means of obtaining the funds necessary to support expanded services?

Following this discussion, the librarians agreed on the need for a strategic plan to address these and other issues. They also agreed that a thorough needs assessment was critical to the strategic plan's validity.

The librarians hired a consultant, a faculty member from the Emporia State University School of Library and Information Management who had worked as a hospital librarian for eleven years and whose doctoral dissertation examined the physician curbside consultation [4], to oversee the project.

The needs assessment addressed two overarching questions. First, how could the libraries best serve their patrons, given realistic limitations on time, resources, and personnel? Second, given these limitations, how could the libraries best help the medical center improve patient care and outcomes?

METHODS

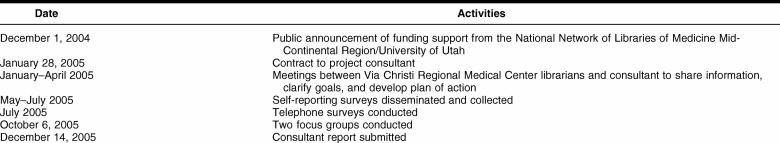

The project timeline is shown in Table 1. During the four-month initial phase of the project, the Via Christi librarians, the project consultant, and the Via Christi Foundation grants coordinator clarified the project goals and developed a plan of action. Using models created by the consultant to guide their discussion, the librarians delineated their potential customer base and geographic service area. They also collected and discussed data on services provided, utilization of library resources, types of information requested, and other relevant activities.

Table 1 Needs assessment timeline

Data collection instruments

As suggested by Lincoln and Guba [5], triangulation— in this case, the use of three different instruments for data collection, including a self-reporting survey, telephone interviews, and focus groups—was employed to ensure credibility of the study findings.

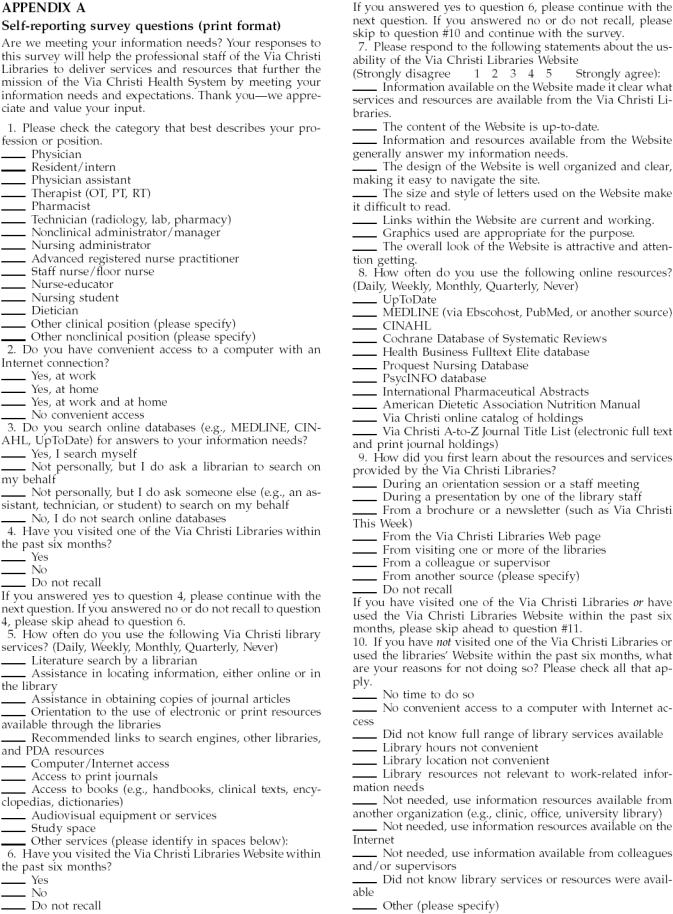

Self-reporting survey

The project consultant used information gained during preliminary discussions with the librarians to draft the first of several iterations of the self-reporting survey. The librarians reviewed each draft and provided feedback until agreement was reached on a version to pilot test with selected users. The pilot test was conducted with six representative library users to determine the clarity and ease of use of the survey. The project consultant used feedback from the pilot test respondents and the librarians who administered the survey to arrive at the final draft (Appendix A).

The self-reporting survey began with an initial set of questions dealing with the respondent's profession or position, computer use, information search habits, and frequency of library use. At that point, branching was used to route respondents to two different sections of the survey: one for those who had used at least one of the Via Christi Libraries within the past six months and one for those who had not used the libraries during that time (nonusers). A combination of question formats was used, including checklists, scales, and requests for narrative responses. At the end of the survey, all respondents were asked to respond to the open-ended question, “What else should the Via Christi librarians know to better align library services to your information needs and expectations?”

Two versions of the survey were created, one print and one Web-based. Each version took approximately six minutes to complete. The print surveys and informed consent forms were distributed by the Via Christi librarians during presentations at medical center meetings and during a number of appearances in the cafeterias of the various hospital campuses. The Web-based self-reporting survey, which included an online version of the informed consent form, was created using the commercial version of SurveyMonkey. The Web-based survey was disseminated via a link placed on the medical center intranet site.

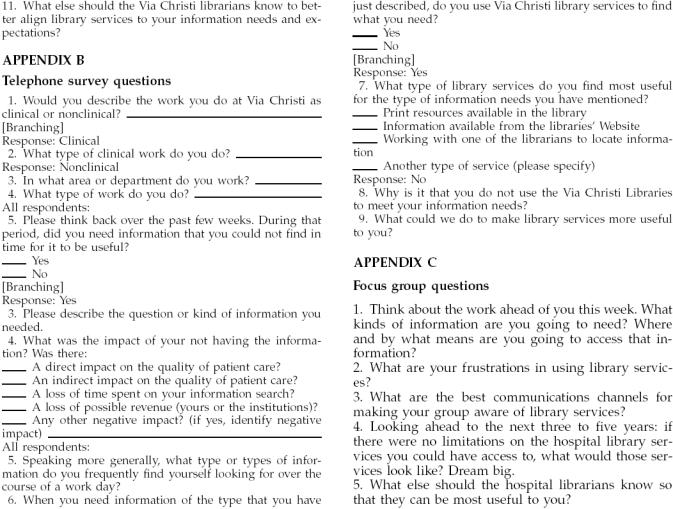

Telephone interviews

Data collected from the self-reporting surveys were employed to identify issues warranting further investigation. The project consultant used these considerations to identify questions to be asked in the telephone surveys (Appendix B), which was scripted into SurveyMonkey. Two surveyors employed to conduct the telephone interviews used the Web-based software to structure each call and record the responses as they were provided. The telephone survey took approximately five minutes to administer. It was pilot-tested with five respondents to ensure clarity and ease of use and then administered to the remaining seventy respondents.

Focus group interviews

Data from both the self-reporting surveys and telephone interviews were used to create questions asked during the focus group interviews (Appendix C). Instead of repeating the same questions, however, the consultant asked respondents to “dream big.” The purpose of doing so was to elicit different, perhaps innovative perspectives that the librarians and the consultant might not have considered. Two one-hour focus groups were conducted, one with nine physicians and one with nine clinical and administrative personnel.

Respondents

During preliminary discussions, the librarians determined that the needs assessment should involve as many existing and potential library users as possible. The target population, therefore, included approximately 900 physicians and residents working at VCRMC as well as approximately 5,000 medical center staff, both clinical and nonclinical.

Librarians employed multiple organizational communication venues—including the medical center's in-house newsletter, poster displays, intranet, and email messages—to inform physicians and VCRMC staff about the needs assessment, including its purpose, funding, and potential impact on library services.

In keeping with VCRMC institutional guidelines, the Via Christi grants coordinator reviewed and approved the data collection methods. The grants coordinator also created the informed consent form completed by each needs assessment respondent. Signed forms were collected and filed separately from the collected data to maintain respondent anonymity.

A section of the informed consent form included an invitation to volunteer for the telephone interview, a focus group, or both activities. Of the 1,295 respondents who completed the self-reporting survey, 232 agreed to participate in the telephone interview, 59 agreed to participate in a focus group and 36 volunteered to participate in either a telephone interview or a focus group. The names of those respondents willing to participate in a telephone interview were randomly organized in a calling list and contacted in that order until the goal of completing 75 interviews was reached.

Finding a sufficient number of focus group participants proved more difficult. A number of respondents who initially volunteered to participate later declined. Another complicating factor involved scheduling the two focus group meetings at times that would work for the respondents. To fill the two focus groups, librarians recruited respondents in person, by electronic mail, and by telephone.

All respondents received a token of appreciation for their participation. Those who completed the print survey received a pen with the Via Christi Libraries logo and Web address, a free soda, a cookie, and a chance to register for a $50 grand prize gift certificate. Those who completed the Web-based survey were offered a similar prize, redeemable at any of the libraries upon providing a “secret word” included at the end of the survey. Telephone survey respondents were offered a cafeteria food coupon and a tape measure. Focus group participants received refreshments and two movie passes.

Data analysis

Quantifiable data collected from the self-reporting surveys were tabulated and entered into an Excel spreadsheet, which made it possible to query, display, and examine data from a number of perspectives. As discussed by Miles and Huberman [6], detailed analysis of the distribution of data from each perspective revealed which elements occurred often, which appeared significant, and which seemed to go together. The results of each Excel query provided a different perspective from which to identify frequencies, relationships, themes, and patterns.

A similar, inductive process was to used analyze narrative data drawn from the self-reporting surveys, the telephone interviews, and the focus groups. The consultant used procedures outlined by Lincoln and Guba [5] and Miles and Huberman [6] to categorize, code, and interpret the data. The process began with close examination of narrative responses collected from the self-reporting surveys to identify elements that appeared with some frequency as well as anomalies, elements that did not seem to fit with the rest of the data. Clusters of data that emerged from this detailed examination were organized into broad categories (i.e., time, online information resources, library services in general, repackaging services, user preferences, audiovisual equipment and use, and patient education) and then into subcategories. Next, the coded data were displayed in a series of matrices to reveal relationships—elements that occurred together with some frequency. Narrative data from the telephone interviews and the focus group discussions were analyzed in the same manner.

RESULTS

Self-reporting survey

From a potential pool of approximately 5,900 respondents, 1,295 (22%) completed the self-reporting survey. In some instances, more or less than 1,295 responses were provided in answer to survey questions. Some respondents checked more than 1 response on the written survey, and others skipped questions. In a few instances, Internet survey respondents who received browser error messages resubmitted their original responses. Numbers and percentages are therefore based on the total number of responses to the question at hand.

All respondents were asked to answer questions dealing with their profession or position, computer use, online database searching preferences, and frequency of library use. When asked their profession or position, 158 (12% of 1,316 responses) identified themselves as physicians, residents, interns, or physician assistants; 403 (31%) as nurses or nursing students; 550 (42%) as professionals or personnel in other clinical areas; and 205 (15%) as nonclinical personnel. When asked if they had access to a computer with an Internet connection, only 48 respondents (4% of 1,314 responses) indicated no convenient access either at work or home, and 861 (65%) indicated access both at home and work. In regard to searching online databases, 869 (66% of 1,307 responses) said they searched online databases for themselves rather than asking anyone else to do so; 53 (4%) asked a librarian to search on their behalf; 50 (4%) asked someone other than a librarian to search on their behalf; and 335 (26%) indicated that they did not search online databases at all.

At this point in the self-reporting survey, respondents were branched in 1 of 2 directions. When asked if they had visited any one of the Via Christi Libraries in the past 6 months, 541 (41% of 1,313 responses) respondents (identified for the purposes of this study as “library users”) said that they had visited at least 1 of the libraries during that time and were routed to questions related to their use of library services. The remaining 772 respondents, who reported that they had not or did not recall visiting a Via Christi library within the past 6 months (identified for the purposes of this study as “library nonusers”), were routed to questions related to their information needs.

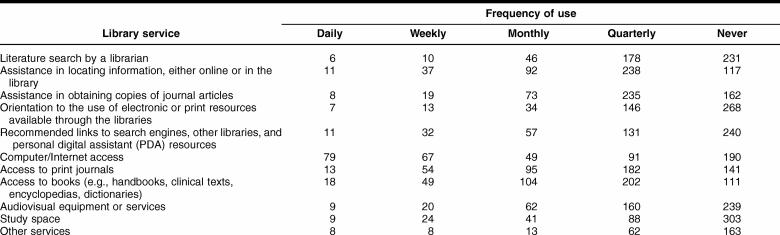

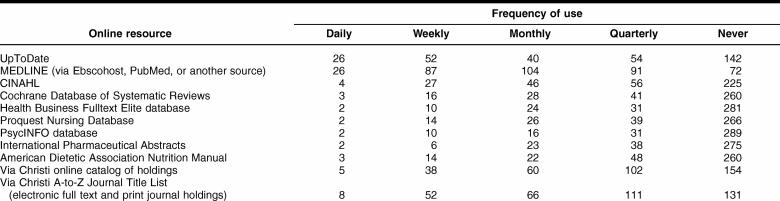

Respondents who identified themselves as library users were asked to respond to questions about the frequency of their use of library services and resources. Table 2 summarizes responses to a question about frequency of library visits, and Table 3 includes responses to a question about frequency of the use of online resources. When asked how they first learned about the resources and services provided by the Via Christi Libraries, 102 library users (23% of 445 responses) reported that they learned about what was available by visiting one or more of the libraries; 88 (20%) reported that they had first learned about the libraries and library services during an orientation session or a staff meeting; and 71 (16%) reported that they had become acquainted with library resources and services by visiting the Via Christi Libraries Web page. Other sources of this information, in descending order of those reported, included a colleague or supervisor (47 responses, 11%), a brochure or newsletter (45 responses, 10%), a presentation by one of the library staff (36 responses, 8%), or another source (27 responses, 6%). The remaining respondents did not recall how they had first learned about the Via Christi Libraries. When library users were asked how the libraries could better align services to the respondent's information needs and expectations, they most frequently cited the need for increased promotion of library services and resources.

Table 2 Frequency of use of library services reported by 541 respondents identified as library users

Table 3 Frequency of use of online resources reported by 541 respondents identified as library users

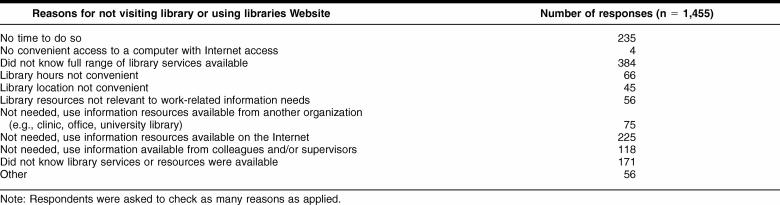

Reasons cited by the 772 respondents who reported that they either had not visited or did not recall visiting one of the Via Christi Libraries within the past six months (library nonusers) are shown in Table 4. Respondents were asked to check as many reasons as applied. Of 1,455 responses received, the most frequently cited reasons involved lack of knowledge about the range of available library services, lack of time, belief that information resources were available on the Internet, and lack of knowledge that library services or resources were available. Narrative responses to an open-ended question about how library services could better meet respondent information needs and expectations expanded on some of the reasons associated with not using library services and resources. For example, one respondent replied, “I'm not sure [of] the library services that are available, so cannot answer that question adequately.” Another responded, “You cannot correct the issue. Work load would have to change to allow time to look up information on the job as needed.”

Table 4 Reasons for not visiting a library or using the libraries' Website reported by 772 respondents identified as library nonusers

Telephone interviews

Of the 75 telephone interview respondents, 2 identified themselves as physicians, 43 as clinical staff, and 30 as nonclinical staff. When asked to think about their information needs during the previous 2 or 3 weeks, 12 of the 75 respondents (16%) indicated that they had needed information that they could not find in time for it to be useful. When asked about the impact of not having the needed information in a timely way, 6 reported a direct impact on the quality of patient care, 6 reported an indirect impact on the quality of patient care, 7 reported a loss of time spent on the search for information, and 3 reported the loss of potential revenue. Eight reported other negative impacts, including not being as prepared as possible, a resulting lack of knowledge, loss of time, and frustration.

When asked how library services could be made more useful to them, respondents suggested making the Internet resources more accessible, publicizing what was available in the library, teaching how to access library services and resources, providing notices of new publications and resources, making computer research easier, and having library materials available on the clinical floor.

Focus group interviews

Responses during the physician focus group indicated that physicians wanted quick, efficient access to quality-filtered patient care information. Some physicians reported that they preferred to access information online, others preferred to access information in print form, and some reported that they were comfortable with both formats. Those who preferred to access information electronically wanted to be mobile as they did so. Some physicians expressed interest in working with the librarians to develop their online skills and organize their electronic documents.

During the focus group with clinical and nonclinical VCRMC personnel, clinicians expressed concern about the need for quality-filtered patient care information and efficient access to patient education materials. Participants in this focus group emphasized the need for information at the point of care, particularly because floor nurses are pressed for time and unable to leave the floor to visit the library. A number of respondents expressed frustration at difficulties related to accessing full-text information quickly and efficiently.

Participants in both focus groups expressed interest in collaborating with the Via Christi librarians to develop customized, innovative solutions to existing, system-wide information needs. Possible collaborative activities included designing, developing, and implementing a “just-in-time” audiovisual review of an upcoming procedure at the scrub sink for surgeons and their residents; customized interfaces to information contained on the libraries' Website and available over the Internet (e.g., information resources and strategies designed specifically for cardiovascular nurses); selective dissemination of information (SDI) searches customized to individual practitioners or to practitioner groups and disseminated on a regular basis; and shared work by physicians, nurses, other clinicians, and the librarians in creating an electronic repository of approved patient education information available from hospital workstations.

DISCUSSION

In a classic article on the work of information professionals, Mason wrote that the goal was “to get the right information from the right source to the right client at the right time in the form most suitable for the use to which it is to be put and at a cost that is justified by its use” [7]. The findings of this needs assessment corroborated this near-mantra for library services. According to respondents, the “right” information was accurate and applicable to the need at hand, while the “right” source was one that was both reliable and readily accessible.

Although they reported that they used the Internet and online resources because they were readily available, respondents acknowledged that their search strategies were not always effective and that “Googling” health information does not necessarily result in quality-filtered information. In terms of the source's format, the findings indicated that the print and electronic resources provided by the libraries appeared to reflect the diversity of their customers' information seeking and use preferences. Although a number of respondents spoke strongly about the importance of having physical access to library resources and to professional interaction with the librarians, a number stressed the need for timely electronic access to information as they moved through their hospital duties. Taken as a whole, the findings suggest that the preference for print versus online resources was not necessarily tied to user age, clinical specialty, or degree of commitment. More often, the choice of format had to do with convenient access to available resources and the knowledge and skills necessary to negotiate existing information systems to find relevant, quality-filtered information in the time allowed. Information that was not available when it was needed was simply not useful, a finding that has been reported in previous studies [8–10].

The Via Christi respondents also indicated a preference for library services and resources that are customized to their discipline's information needs and uses, echoing Mason's construct of the “right client” [7]. Gruppen reported similar findings in a study of physician information seeking [11], pointing out that information needs, preferences, and patterns of seeking and use differ significantly among individual physicians. Gruppen suggested that health sciences libraries conduct market research for the purpose of customizing information services to specific clientele.

The Via Christi study assessed the information needs of physicians, clinicians, and nonclinical hospital staff. Although the impact of library information services was not a focus of the study, telephone interview respondents reported negative impacts when they were not able to locate information within the time allowed. This finding corroborated a number of previous studies on the impact of hospital library information services on clinical care [12–14]. It also corroborated Cuddy's study [15] of the impact of information services on both clinical and nonclinical library users. Given the importance of evidence-based decision making in all areas of a health care organization, the impact of library services on nonclinical hospital activities appears to warrant further investigation.

The use of open-ended questions in this study resulted in an unanticipated finding. At the beginning of the needs assessment process, the Via Christi librarians expected respondents to report what library resources and services they preferred and how the librarians could best deliver these resources and services. What they did not anticipate was discovering the extent to which respondents wanted to increase their professional, collaborative interactions with the librarians. Projects reported by Haigh [16] and Klein-Fedyshin et al. [17] offer examples of the value of this type of multidisciplinary collaboration. However, as Lyon et al. [18] concluded in their study of collaborations in bioinformatics work, librarian visibility is critical to identifying and building productive collaborative projects.

An apparent lack of visibility of the Via Christi Libraries was, in fact, a significant issue. The needs assessment indicated that those respondents who used the libraries and interacted with the librarians held them in high regard. However, of the 772 respondents identified as library nonusers, 384 (50%) cited lack of knowledge of the library services available as a reason why they had not used either the libraries or the libraries' Website, and 171 reported that they did not know that library services were available at all. These and related responses indicated a need for increased visibility and promotion of library services and resources. In a sense, this work has already begun. By encouraging all physicians and VCRMC staff to participate in the needs assessment and by promoting it aggressively via in-person, electronic, and print venues, the librarians raised awareness of the resources and services available. The strategic plan developed after the needs assessment outlines a number of strategies for continuing to address this information deficit.

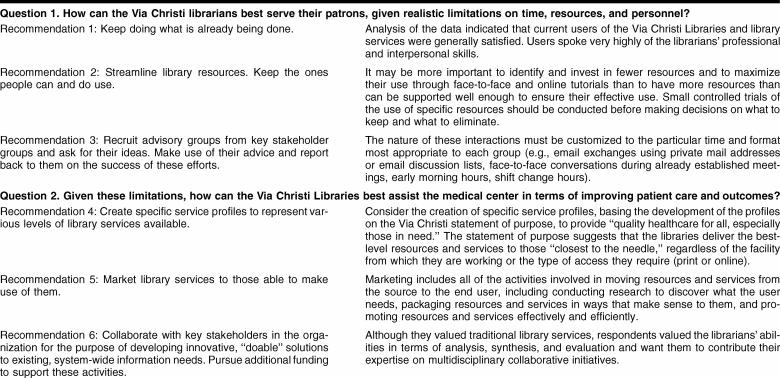

Support for the strategic plan

Although a process was in place to collect data and report on the use of library resources and services, these routine information-gathering methods did not yield the kind of evidence necessary to support developing a strategic plan that was both realistic and visionary. The needs assessment was designed and implemented to provide that evidence. Following data analysis, the consultant generated a list of formal recommendations (Table 5).

Table 5 Consultant's recommendations in response to primary needs assessment questions

The strategic planning process was conducted by the librarians in a series of seven half-day retreats that included brainstorming, revising the libraries' mission statement to better reflect the findings and recommendations of the needs assessment, and developing objectives to accomplish the consultant's recommendations, adopted as goals. As discussions continued, the librarians broadened the goals further. When consensus was reached on the content of the goals, one of the librarians revised the wording of the document to reflect a common voice. The final draft of the strategic plan was completed in April 2006 and reviewed and approved by VCRMC's chief executive officer in May.

As approved, the strategic plan consists of six goals. Each goal is supported by a set of objectives, together with specific strategies for achieving each objective. An evaluative objective identified for each goal specifies the means by which activities can be assessed. Key elements of the strategic plan include a commitment to adapt and expand library information services as warranted by changes in the health care environment, development of customized service patterns, collaborative initiatives undertaken with key stakeholders across the medical center to meet system-wide goals, strengthened communication channels, promotion of library services to all entities in the system, a plan for the effective utilization and enhancement of financial resources, and an outline of the means by which the libraries will demonstrate service value to the VCRMC administration.

Lessons learned

Use of multiple data collection instruments increased the credibility of the study findings [5] and provided different, complementary points of view from which to examine participant responses. Each instrument also invited respondents to provide narrative, unstructured answers to questions about how library services and resources could better address their information needs. The resulting responses provided fresh, sometimes unanticipated perspectives from which to view library resources and services. On the other hand, conducting such a complex needs assessment and promoting it across the entire medical center consumed a great deal of time. An estimated 250 hours of library staff time was spent on the project, most of it involving promotional activities.

Because one of the project objectives was to reach as many VCRMC physicians, residents, and staff members as possible, creating and disseminating the self-reporting survey in two formats, print and electronic, proved a useful strategy. The commercial version of SurveyMonkey, the online survey software chosen for the task, worked well with the branching technique necessary to query library users and library nonusers, both together and separately. On the other hand, translating the print document to a comparable Web-based document was challenging, particularly with regard to the online informed consent information.

Offering incentives to study respondents encouraged both library users and nonusers to participate. Distributing the print surveys in hospital cafeterias was particularly effective, because respondents generally completed their surveys and received their incentives at that time. Those who responded to the Web-based survey were required to visit the library to collect their incentives. Respondents who worked late shifts were therefore not always able to do so. Prior to the survey, the librarians anticipated a potential problem—that the incentives might motivate some respondents to complete more than one self-reporting survey—but it did not materialize. Because library staff distributed the incentives in person, they were able to verify that this did not occur.

Finally, it proved useful to use SurveyMonkey to script the telephone interviews. The professional callers conducting the interviews were able to use the script to structure the conversations and to input data during each call. The collected data were monitored throughout the process, and the cumulated data were readily available for analysis.

Limitations of the study

The interpretations that can be drawn from this study have limitations. First, respondents for this investigation volunteered to participate and did not constitute a representative or random sample. It should be noted, however, that the results of the self-reporting survey included approximately 20% of the targeted population. Second, comments made by respondents indicated that the act of publicizing and implementing the needs assessment affected their knowledge about the libraries and their services. That is, the very act of asking people about library services heightened the profile of the Via Christi Libraries. Because data collection took place over a period of several months, respondent perceptions may have shifted considerably. No attempt was made to create a control group, so it was impossible to measure the extent of the shift. Third, discrepancies occurred in the numbers of responses to the self-reporting survey because participants could select more than one answer or skip questions. In some instances, respondents using the Web-based self-reporting survey received error messages from their browsers when they attempted to submit their responses. When they resubmitted their answers, the software counted both the first and second sets of responses. To account for these circumstances, respondent numbers and percentages were reported together with the total number of responses received for a given question. Finally, only 2 physicians participated in the telephone interviews, thus data collected from the telephone interviews cannot be considered to represent more than their individual responses. This limitation was ameliorated in part by the participation of 104 physicians and 51 residents or interns in the self-reporting survey and 9 physicians in 1 of the 2 focus groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from the Via Christi Libraries' needs assessment provided the evidence necessary to develop a user-centered strategic plan. In her 1994 Janet Doe Lecture, Matheson [19] called attention to a statement by O'Donnell [20], who asserted that in the twenty-first century, “the library will cease to be a warehouse and become instead a software system.” Matheson expanded on the idea of library as software system, contending that just one institutional system would not be enough. Instead, each discipline would require its own system—one that was “best suited to its knowledge representation and problem-solving needs.” The findings from the Via Christi Libraries' needs assessment indicated both a warehouse and customized variations of a software system were needed by center staff. They wanted the library as a place to find and use print resources, but they also wanted the librarians to provide information services tailored to specific disciplines in the health system. Despite some concerns in the field of library and information science about disintermediation—end users bypassing librarians and librarians to gain direct access to information— the results of this study suggested that in some instances, the roles of hospital librarians might be evolving in a more positive direction—expanding rather than contracting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Via Christi Foundation grants coordinator Martha McCabe and colleagues Phil Omenski, Terri Barnard, and Cheri Sellers for their contributions to this needs assessment.

APPENDIX A

Self-reporting survey questions (print format)

APPENDIX B

Telephone survey questions

Footnotes

* Funded by the National Library of Medicine under contract No. NO1-LM-1-3514 with the University of Utah Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library <http://library.med.utah.edu/>. Additional support provided by Via Christi Volunteers-Partners in Caring.

REFERENCES

- Medical Library Association. Standards for hospital libraries 2002 with 2004 revisions. Natl Netw. 2005 Jan; 29(3):11–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster FW. If you want to evaluate your library. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree AB, Crawford JH. Assessing and addressing the library needs of health care personnel in a large regional hospital. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Apr; 85(2):167–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perley CM. Underlying meanings of the physician curbside consultation [dissertation]. Emporia, KS: Emporia State University, 2001. UMI No.: AAT 3028623. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994:253. [Google Scholar]

- Mason RO. What is an information professional? J Educ Libr Inf Sci. 1990 Fall; 31(2):122–38. [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct; 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly DP, Rich EC, Curley SP, and Kelly JT. Knowledge resource preferences of family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1990 Mar; 30(3):353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight M. The information seeking of on-duty critical care nurses: evidence from participant observation and in-context interviews. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Apr; 94(2):145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruppen LD. Physician information seeking: improving relevance through research. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1990 Apr; 78(2):165–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DN. The contribution of hospital library information services to clinical care: a study in eight hospitals. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1987 Oct; 75(4):291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal JG. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Apr; 80(2):169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med. 1994 Jun; 69(6):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy TM. Value of hospital libraries: the Fuld Campus study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005 Oct; 93(4):446–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh V. Clinical effectiveness and allied health professionals: an information needs assessment. Health Info Libr J. 2006 Mar; 23(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Fedyshin M, Burda ML, Epstein BA, and Lawrence B. Collaborating to enhance patient education and recovery. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005 Oct; 93(4):440–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon JA, Tennant MR, Messner KR, and Osterbur DL. Carving a niche: establishing bioinformatics collaborations. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Jul; 94(3):330–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson NW. The idea of the library in the twenty-first century. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995 Jan; 83(1):1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell JJ. St. Augustine to NREN: the tree of knowledge and how it grows. In: Strangelove M. Directory of electronic journals, newsletters and academic discussion lists. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1993:1–11. [Google Scholar]