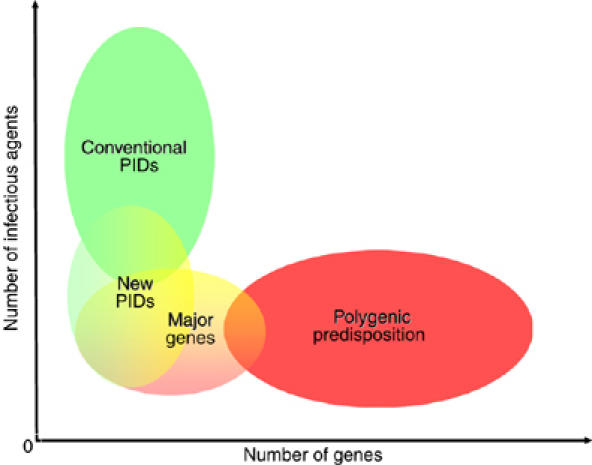

Figure 1.

Human genetics of infectious diseases. The spectrum of genetic predisposition to infectious diseases in human patients is represented, according to the number of genes involved (x-axis) and the number of infections (y-axis). The dominant view in human genetics of infectious diseases postulates that rare, ‘conventional', monogenic primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs, in green) predispose the individual to numerous infections (one gene, multiple infections), whereas common infectious diseases are associated with polygenic inheritance (in red) of numerous susceptibility genes (one infection, multiple genes). Novel monogenic PIDs (in yellow/green) predispose the individual to a principal or single type of infection. Major genes (in yellow/red) exert a nearly Mendelian impact at the population level and largely account for common infectious diseases in some individuals. The recent discovery of such human genes conferring vulnerability or resistance to a specific infection at the individual level (one gene, one infection) bridges the gap between the two classical fields of conventional PIDs and polygenic inheritance, as defined in the 50 s. As an example, genetic predisposition to tuberculosis, which was considered to be purely polygenic, was recently shown to reflect both new PID and major gene effects, at least in some patients (see text for details). Overall, these observations provide experimental support for a continuous spectrum of predisposition and a unified theory of the human genetics of infectious diseases.