Barrett's oesophagus is the eponym used to describe the change from the normal stratified, squamous epithelium of the lower oesophagus to a polarised, columnar‐lined epithelium with intestinal‐type differentiation.1 This condition develops in the context of chronic gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)2 and is associated with a 0.5–1% annual conversion rate to oesophageal adenocarcinoma.3,4 The overall 5‐year survival rate in patients presenting with symptomatic adenocarcinoma is a dismal 13%.5 An understanding of the molecular basis for the development and progression of Barrett's metaplasia is required to develop effective clinical management strategies. Before discussing the molecular changes at the level of the tissue, it is important to briefly consider the environmental and inherited genetic factors that contribute to an individual's susceptibility to these conditions.

Effect of environmental and inherited factors on individual susceptibility

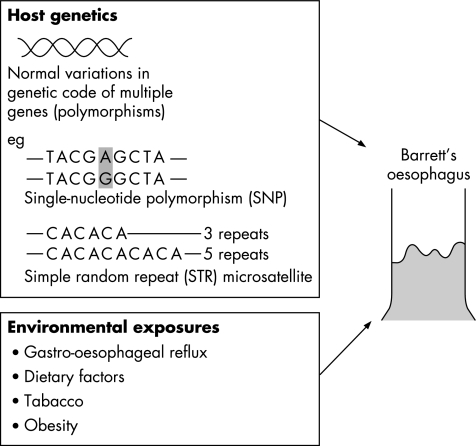

The role of environmental factors is evident from the short time period over which the incidence of Barrett's oesophagus6 and oesophageal adenocarcinoma7 has increased. Furthermore, the demonstration of a “birth cohort effect”, with higher incidence rates in younger cohorts,8 would support the idea that exposure to environmental factors in early life is an important determinant of risk. Identification of specific environmental exposures is difficult, but factors that increase gastro‐oesophageal reflux, such as dietary components, increasing body mass index and eradication of Helicobacterpylori, may be relevant.9 Whether or not smoking and alcohol consumption are risk factors for Barrett's oesophagus is controversial; however, an association was found in a recent population study.10 In order for an individual to develop Barrett's oesophagus, and in some cases oesophageal adenocarcinoma, these environmental exposures probably need to interact with genetically determined characteristics that define personal susceptibility11 (fig 1). As most cases are sporadic, occurring in the absence of a family history, these inherited genetic factors are likely to be normal variations or polymorphisms in multiple genes rather than single gene mutations. In Barrett's oesophagus, polymorphisms in genes involved in DNA repair, chemical detoxification and cytokine responses have been identified.12,13,14 However, to reliably detect the low to moderate risks expected to be associated with multiple genetic polymorphisms, large, population‐based case collections are required, with comprehensive epidemiological, clinical and pathological data.15 In summary, Barrett's oesophagus occurs in the context of inherited genetic susceptibility loci and specific environmental exposures. The remainder of this review is concerned with the molecular changes in the oesophageal tissue in the development and progression of Barrett's oesophagus.

Figure 1 The likelihood of an individual developing Barrett's oesophagus might be determined by a combination of host genetics and environmental factors. The host genetics will include normal variations in multiple genes including polymorphisms and microsatellites. Examples of these changes are shown. The specific genes involved and the identification of particular environmental factors are still being elucidated.

Induction of Barrett's metaplasia

The process of metaplastic change is rarely observed in vivo and there are no reliable, physiological animal models. As a result, the theories attempting to explain the molecular and cellular processes underlying the development of Barrett's oesophagus are rather speculative. However, it has been established that the luminal environment might be important. Cells of the human oesophageal epithelium are under relatively unique environmental pressures, being exposed on a daily basis to thermal stress, unmetabolised chemicals or food products. For Barrett's oesophagus to develop, chronic exposure to refluxed duodenal and gastric juices seems to be critical. Hence, all of the proposed theories for the origin of Barrett's oesophagus have in common the suggestion that luminal damage of the epithelium is required at the outset. It has also become apparent that Barrett's metaplasia is likely to originate from within the oesophageal compartment rather than from overgrowth of neighbouring gastric tissue, as animals can still develop columnar oesophagus when there is a mucosal defect separating the distal oesophagus from the transitional zone.16,17

Cell of origin

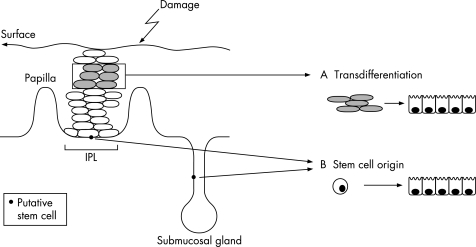

The metaplastic conversion of the oesophageal squamous epithelium to a columnar‐lined epithelium could arise from two different categories of cell. One possibility is the direct conversion of differentiated cells in the absence of cell proliferation, a process called “transdifferentiation”. Alternatively, metaplasia may develop from the conversion of a “stem” or “pluripotential cell”, meaning a cell with the capacity for unlimited or prolonged self‐renewal18 (fig 2).

Figure 2 Possible cells of origin for Barrett's metaplasia. If the metaplastic process occurs by altered differentiation of a mature squamous oesophageal epithelial cell (shaded cells in grey in the mucosal layer) without requiring proliferation, it is called transdifferentiation. Alternatively, the cell of origin may be an undifferentiated cell with the capacity to form multiple‐cell lineages: a so‐called “stem cell”. These stem cells may be of tissue or bone marrow origin. The tissue‐derived stem cells may be located in the basal compartment of the interpapillary layer or in the submucosal gland duct. In either case, the trigger for columnar differentiation seems to depend on surface epithelial damage from luminal factors.

Recent evidence for transdifferentiation has come from in vitro culture of embryonic mouse oesophagus. These experiments take advantage of the normal developmental process whereby the oesophagus undergoes a columnar to squamous cell transition at 18 weeks of gestation.19 The evidence suggests that the cells in the squamous basal layer arise directly from columnar tissue, independent of squamous cell proliferation or apoptosis of columnar cells.20 An extrapolation of this work is that in adulthood the reverse transdifferentiation process could account for the generation of Barrett's metaplasia in the context of GORD. However, the embryological maturation event may be quite different from the pathological development of metaplasia. Evidence against transdifferentiation comes from the observation that new squamous epithelium can develop after ablation treatment in which the Barrett's epithelium has been completely eliminated.

With regard to the stem cell theory, the squamous oesophageal stem cells are thought to reside in the interbasal layer of the epithelium between the papillae.21 Possibly, there are stem cells in the glandular neck region of oesophageal submucosal gland ducts similar to those found within the bulge region of the hair follicle.22 Hence, after ulceration or damage, stem cells may grow out to form a new gland in the lamina propria, finally giving rise to a duct by which the glandular cells are carried to the surface.16,23 The basis for this mechanism is the ulcer‐associated cell lineage.24 Whether the normal squamous and Barrett's epithelial cells arise from the same or different progenitors is not clear. However, recent mutational data that examine squamous islands compared with the surrounding Barrett's epithelium suggest that in most cases the progenitor cells seem to be different for each tissue type.25

As well as tissue‐specific stem cells, it is now known that bone marrow‐derived stem cells (BMDCs) have such a surprising degree of plasticity that they could also give rise to diverse epithelial cell types.26 Bone marrow‐derived epithelial cells have been identified throughout the gastrointestinal tract 11 months after transplantation of a single purified haematopoietic BMDCs.26 The local tissue environment, such as continued inflammation and injury, seems to have an important role in this process.27 This concept is well illustrated by the demonstration of BMDCs in the murine stomach after Helicobacter‐induced chronic gastritis. These BMDCs had a classical metaplastic phenotype, which gradually progressed to dysplasia and neoplasia.28 Obvious parallels can be drawn between this model and Barrett's carcinogenesis, although there is no direct evidence at the current time for the role of BMDCs in this disease. Whether the progenitor cell arises from within tissues or the bone marrow, the stem cell origin would more easily explain the perpetuation of the metaplastic phenotype once it had occurred.

Determinants of cell fate

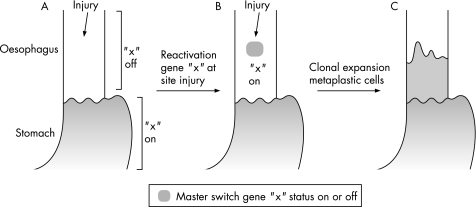

The control of cell fate is likely to be achieved by a combination of internal and external cell signals. Internal signals may include nuclear factors controlling gene expression. External signals are likely to be reflux components, secreted factors and the factors responsible for cell–cell adhesion, such as extracellular matrix proteins. One possibility is that genes responsible for the physiological transition from columnar to squamous oesophagus in embryogenesis may be abnormally reactivated, leading to the development of metaplastic Barrett's oesophagus in adulthood. For example, in the embryo, a morphogenic gradient may induce activation of specific genes resulting in one tissue type (eg, gastric epithelium), whereas non‐induction of those same genes may lead to a completely different tissue (squamous oesophageal epithelium). If pluripotential cells of the squamous oesophagus still require inactivation of the same genes in adult life to maintain their stratified squamous differentiation structure, then re‐activation of those genes may lead to an area of columnar metaplasia29 (fig 3). One example in support of this theory is the conversion of pancreas cells to liver cells, which can be achieved by induction of a single transcription factor.30 It is not yet known whether a similar process occurs in the oesophagus.

Figure 3 The molecular mechanism for Barrett's metaplasia may result from change in the activation status of a gene as a result of injury. The example shown here is activation of gene “x” in the oesophagus. This hypothetical gene would ordinarily be switched off during embryogenesis when the oesophagus changes from a columnar‐lined epithelium to a squamous epithelium. Reactivation of that gene may lead to a patch of columnar tissue, which may then grow to occupy the lower part of the oesophagus as a result of clonal expansion. This process could also involve inactivation of a gene and there may be multiple genes involved.

There are several candidate genes for oesophageal metaplasia, although their possible involvement is mainly derived from evidence in other organ systems. The discussion here is restricted to some evidence‐based examples.

p63 transcription factor

p63 is a homologue of the tumour suppressor and transcription factor p53. p63 is normally absent in simple, columnar epithelia, but is expressed in the basal layer of squamous epithelia. Recently, it has been shown that p63 is essential during normal oesophageal development. p63 knockout mice developed highly ordered, columnar, ciliated oesophageal epithelium.31

Homeobox genes Cdx1/2

The homeobox or HOX family of genes are developmental transcription factors. Various evidence suggests that Cdx2 is a “master switch” gene whose normal expression determines the proximal and distal specialisation of the gut in embryogenesis.32 In adulthood, Cdx1/2 protein is predominantly expressed in the small intestine and colon, but not in the stomach or oesophagus.33 Transgenic mice overexpressing Cdx2 develop intestinal metaplasia in the gastric epithelium34 and, conversely, the loss of Cdx2 leads to the development of polyp‐like lesions in the intestine containing areas of squamous epithelium. Interestingly, the oesophagus‐like squamous lesions are flanked by heterotopic gastric epithelium.35 This is a process called intercalary regeneration, by which tissue regeneration occurs at a junction between experimentally produced body parts to “fill in” those parts that normally lie between them. With regard to Barrett's metaplasia, Cdx2 expression is observed in areas of intestinal metaplasia.36,37,38 Gastric metaplasia, which is also commonly observed in Barrett's oesophagus, could be a form of intercalary regeneration. This is in contrast with the theory that gastric‐type metaplasia develops before the intestinal type.39

Extracellular matrix components

To achieve asymmetrical stem cell divisions of the oesophageal epithelium, it is necessary to reconstitute the oesophageal squamous keratinocytes on denuded connective tissue containing oesophageal laminin 2. Oesophageal keratinocytes cultured on connective tissue from the skin failed to show the expected pattern of differentiation.21 Furthermore, conversion of embryonic stem cells to columnar or squamous epithelia has been shown to depend on the components of the extracellular matrix.40

Cytokines and transforming growth factor β

In GORD, the supporting oesophageal stroma becomes infiltrated with inflammatory cells, and it has been shown that the cytokine profile of Barrett's oesophagus is fundamentally different from oesophagitis.41,42 Barrett's oesophagus has increased levels of T helper 2 (anti‐inflammatory) cytokines and a reduction in the ability to signal through the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) cascade owing to a decrease in the expression of the signalling components TβRII, Smad2 and Smad4.43 Whether this change in TGFβ signalling contributes to the induction of Barrett's oesophagus or arises as a consequence of its development is unclear; however, several lines of evidence support a causative role for reduced TGFβ. Targeted loss of TGFβ signalling components in mice has shown that this pathway has an important role in the development of various organs and tissues such as heart, bone and vasculature.44 Thrombospondin 1 knockout mice express low levels of active TGFβ and have altered cell differentiation in their distal oesophagus,45 amounting to focal areas of columnar epithelium. We could speculate how according to the model of metaplasia discussed above29 (fig 3), a reduction in TGFβ signal propagation could decrease the expression of factors necessary for maintaining squamous differentiation, resulting in the formation of focal areas of Barrett's oesophagus.

Mechanisms for change in gene activation state

The triggering mechanisms by which specific genes are activated or silenced, leading to the development of Barrett's metaplasia, is not understood. There are many levels of control and these may be direct genetic (eg, mutations in specific genes) or epigenetic (non‐sequence‐based changes that are inherited through cell division) modifications.

Examples of epigenetic silencing include the addition of methyl groups to the Cdx1 promoter.46 The transdifferentiation process in embryonic mouse oesophagus, discussed earlier, occurs by methylation of the keratin 8 promoter.20 Loss of TGFβ signalling occurs owing to several different mechanisms, including methylation, gene deletion and protein modification.43

In view of the role of GORD in the pathogenesis of Barrett's oesophagus, it is interesting to know how this may directly affect gene expression. The gastroduodenal refluxate is a complex mixture of bile salts and dietary components at variable pH. Whether the refluxate is genotoxic will depend on its specific constituents. However, even those refluxate components that are not directly genotoxic47 may have profound effects on cell signalling and induce epigenetic effects on postmitotic cells. For example, nuclear factor κB may be activated by components of refluxate and inflammatory cytokines, which may in turn affect the expression of Cdx1/2.46,48 Chronic acid exposure has been shown to induce Cdx2 expression in primary mouse squamous oesophageal cells.49 This, coupled with the observation that Cdx2 mRNA is expressed in oesophagitis before the induction of Cdx1 or other intestine‐specific genes,36 offers a possible link between gastro‐oesophageal reflux exposure and the molecular basis for metaplasia. Mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways can also be activated by gastro‐oesophageal reflux exposure,50 and variations in integrin expression are known to regulate cell differentiation via MAPK signalling.51 Hence, through multiple cell signalling pathways, exposure to refluxate may have effects on cells that are removed from the site of the original stimulus. This may explain why the stem cell niche could be affected by exposure to refluxate even in its basal interpapillary location distant from the luminal surface (box 1).

Malignant transformation

The progression of Barrett's oesophagus to adenocarcinoma is generally thought to occur when a single Barrett's epithelial cell is transformed into a cancer‐initiating cell (cancer stem cell) through a series of genetic changes. The cancer stem cell or progenitor cell is a relatively recent term, coined because of its capacity for self‐renewal. When the environment is conducive to multiple rounds of cell division, this may lead to malignant growth.

Box 1: Induction of Barrett's metaplasia

Luminal factors such as reflux components might be involved in causation.

-

Barrett's metaplasia could arise from

-

-

transdifferentiation of a mature squamous cell,

-

-

tissue‐specific or bone marrow‐derived pluripotential stem cell.

-

-

-

Multiple levels of control over cell fate

-

-

cell signalling pathways,

-

-

genetic and epigenetic effects on cell‐activation status.

-

-

Luminal environment can exert effects on cells distant to stimulus via cell signalling pathways.

In the development of cancer, the occurrence of sequential genetic changes are responsible for clonal selection and tumour heterogeneity. The age‐dependent incidence of many cancers including oesophageal cancer implicates four to seven rate‐limiting, stochastic events.52 It is now becoming clear that although the nature and timing of these genetic events may be extremely variable, for an invasive carcinoma to develop, the specific genetic changes are not as important as the acquisition of certain biological capabilities. Six essential steps have been described for the development of cancer: self‐sufficiency in growth, evading apoptosis, insensitivity to anti‐growth, limitless replicative potential, sustained angiogenesis, and ability for invasion and metastasis.53 In Barrett's carcinogenesis there is clear documentation for all of these biological characteristics, and the causative genetic changes may be as subtle as point mutations and as obvious as changes in chromosome complement.54,55 This discussion will include possible mechanisms for the acquisition of cancer‐prone properties rather than presenting an exhaustive catalogue of the myriad genetic changes that have been the subject of other reviews (box 2).56,57

Abnormal growth

The first three biological capabilities are all related to abnormal growth. In Barrett's carcinogenesis, this can be clearly seen in the increased expression of proliferation markers such as mini‐chromosome maintenance proteins, with a shift in the proliferative compartment towards the surface.58,59,60 These proliferation abnormalities predate the development of dysplasia58 and are in keeping with the observed increase in the S phase (or DNA synthesis phase) of the cell cycle, which is an independent predictor of progression to cancer in Barrett's oesophagus.61 Interestingly, despite early loss of the p16 gene,62,63 which controls the G2/S transition of the cell cycle, there does not seem to be an intrinsic abnormality in cell‐cycle stage in Barrett's carcinogenesis.60 This is in keeping with recent data obtained from gene expression profiling (whereby the expression of a large number of genes across the entire genome can be assayed simultaneously using microarray technology) in which there was no clear evidence that differential genes involved in cell‐cycle regulation contributed to increased cell proliferation in Barrett's carcinogenesis.64 This suggests that abnormal cell cycle entry or exit and possibly a shortened cell cycle length may be responsible for the increased proliferative index.

Box 2: Malignant transformation of Barrett's metaplasia

Sequential genetic changes confer biological advantage.

Changes include genetic, epigenetic and gross chromosomal changes.

Biological characteristics acquired include abnormal growth control and increased invasion.

Chronic reflux exposure may contribute to pro‐proliferative drive.

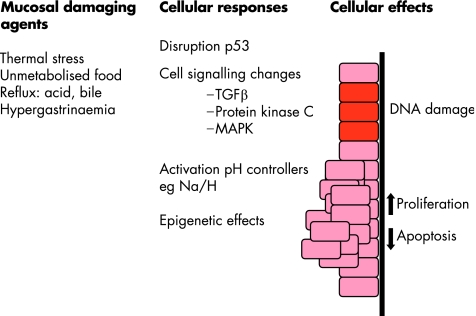

This general increase in proliferation would be in keeping with the idea that the micro‐environment, including chronic, pulsatile exposure to luminal factors, is the pro‐proliferative driver50,65 (fig 4). The acid‐induced hyperproliferation appears to be dependent on activation of the Na+/H+ exchangers, that regulate intracellular pH in Barrett's oesophageal cells, which in turn activate the p38 MAPK pathway to turn on mitogenic and antiapoptotic transcription factors.66,67 In addition, activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger leads to transient cytoplasmic alkalinisation,66 which is crucial for cells to progress from the G1 to S phase of the cell cycle.68 By using a similar in vitro model, it has since been shown that pulsatile bile exposure can also induce hyperproliferation via effects on protein kinase C.69 Repetitive exposure to GORD will also induce inflammation and hence changes in growth factors and cytokines. TGFβ is a good example of an immunoregulatory pathway that is commonly disrupted in Barrett's carcinogenesis, leading to insensitivity to growth signals.70 The lack of TGFβ responsiveness is associated with a profound and progressive reduction in Smad4 that correlates with progression through the metaplasia–dysplasia–adenocarcinoma sequence.43

Figure 4 A summary of the pathways by which various mucosal damaging agents (left‐hand column) may lead to changes in specific genes and cell signalling pathways (middle column) and hence to a variety of cellular effects (right‐hand column), which may increase the propensity for cancer to develop. TGFβ, transforming growth factor β; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinase.

Overall, the persistent proliferative drive through exposure to luminal factors may explain the relative paucity of key oncogenes causally implicated in Barrett's adenocarcinoma.

Evading apoptosis

Tissue growth is determined by the balance between cell death and proliferation. Reduced programmed cell death or apoptosis has been well‐documented in many cancers, including Barrett's carcinogenesis.70,71 Several genes are involved in controlling apoptosis, and expression profiling has shown that several of these are down regulated in the progression from Barrett's oesophageal epithelium to cancer,64 including survivin and caspases.72,73,74 The microenvironment is an important determinant for the apoptotic index in a similar way to that discussed in the context of proliferation. In vitro exposure of an oesophageal adenocarcinoma cell line to acid led to the immediate down regulation of genes associated with apoptosis and early up regulation of genes associated with proliferation.67 The gene expression profiles suggest that MAPK pathways may be involved and suppression of apoptosis may occur via p53‐dependent mechanisms.67 Decreased expression of Fas results in resistance to Fas‐mediated apoptosis in oesophageal adenocarcinoma.75 The mechanism for this seems to be mediated via the Src kinase Yes, which is an upstream target of bile acids.76 The gastrin CCK2R receptor can also affect transcription of Fas via the phosphorylation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) and in vitro evidence suggests that gastrin may aid progression of antiapoptotic pathways via these signalling mechanisms.77 This may be relevant for patients with hypergastrinaemia secondary to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis

Angiogenesis is required to maintain tumour growth and to facilitate invasion and vascular spread. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a well‐described determinant of new vessel formation, and this growth factor is expressed by the Barrett's epithelial goblet cells and by the immature blood vessels that develop before the development of invasive adenocarcinoma.78,79 The cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) enzyme also has a role in inducing angiogenesis80 as well as effects on immune surveillance, tissue growth and cell adhesion. The role of COX2 in the progression of Barrett's oesophagus is somewhat conflicting.81,82,83 In a longitudinal case–control study, the COX2 expression levels in patients increased over time, regardless of the degree of malignant progression, and were independent of the tumour differentiation status or the degree of inflammation.84 Acid and bile have been shown to increase COX2 expression85, and interestingly, gastrin markedly induced COX2, prostaglandin E(2) and cell proliferation in biopsy specimens and cell lines that could be inhibited by CCK2R antagonists.84 Hence, the increase in COX2 expression could be occurring secondary to PPI use.

Wnt glycoproteins comprise a family of extracellular signalling ligands that have essential roles in the regulation of cell growth, motility and differentiation. Mutations in Wnt signalling molecules are carcinogenic through activation of β‐catenin‐TCF (T cell factor/lymphocyte enhancer factor) signalling. Previous studies86 have reported that nuclear accumulation of β‐catenin is an indicator of activation of Wnt/β‐catenin signalling, and this nuclear accumulation has been found in Barrett's carcinogenesis. However, as mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) are rare, the mechanism of Wnt pathway activation has not been clear. Recent evidence suggests that the APC and SFRP1 (secreted frizzled‐related protein) genes are inactivated by promoter methylation.87 However, as the loss of 5q and methylation of APC can occur both before and after the emergence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, this suggests that the loss of APC is not necessary for cancer progression. This highlights the fact that during the genetic evolution of Barrett's cancer there will be “hitchhiker lesions”. In other words, non‐causative genetic lesions may occur and spread over large areas of the Barrett's oesophageal mucosa if they coexist with a selectively advantageous lesion that undergoes clonal expansion.88 Therefore, not all genetic changes identified will have a causative role unless they confer a biological advantage on cell behaviour.

Genetic instability

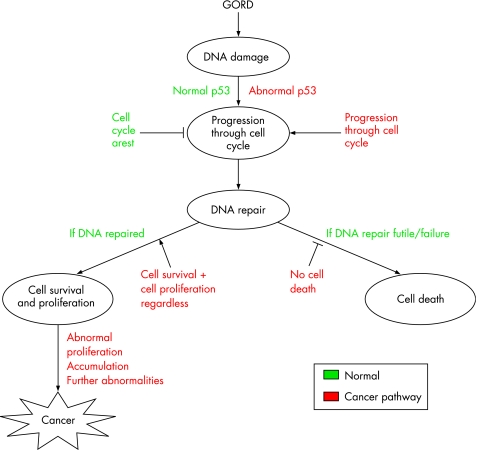

The propensity for these six tumorigenic steps to occur is increased by underlying genetic instability. Reflux exposure has been shown to cause non‐specific DNA damage,89 and the most prominent gene abnormality that promotes mutagenesis in response to DNA damage is the loss of the p53 tumour suppressor protein. When DNA damage occurs and p53 is functioning correctly, it leads to cell‐cycle arrest to allow for DNA repair or apoptosis if the damage is excessive. Hence, in a normal cell, there are enough biological checkpoints in place to prevent premalignant cells progressing towards cancer (fig 5). In most, if not all human cancers, the p53 DNA damage signalling pathway is lost,90 and Barrett's adenocarcinoma is no exception.55,91,92,93,94,95 Reid et al have shown that p53 loss most commonly occurs via mutation followed by loss of a chromosomal region, an event called loss of heterozygosity. Loss of p53 gene expression can occupy large areas of the Barrett's oesophageal mucosa via clonal expansion.95 A proteomics approach also identified up regulation of an oestrogen receptor‐responsive protein called anterior gradient‐2 in Barrett's oesophagus as an alternative way of silencing the p53 transcriptional response to DNA damage.96 In addition, there is evidence that environmental agents, such as a low oxygen concentration, low extracellular pH and thermal injury, can activate p53 protein and play a part in tissue transformation.97,98

Figure 5 The chronic injury imposed on the oesophageal epithelium as a result of gastrooesophageal reflux may result in non‐specific DNA damage, resulting in an increased propensity for further genetic abnormalities predisposing to cancer. Abnormalities in the tumour suppressor gene p53 are common in the progression of Barrett's oesophagus. Changes in this pathway will prevent the cellular checking mechanisms, that normally prevent the perpetuation of genetic errors (green type depicts the normal cellular response and red type the abnormal response). GORD, gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease.

Epigenetic changes are another causative mechanism for genomic instability. These may be global changes such as hypomethylation or hypermethylation of DNA, changes in the histones which make up the chromatin, as well as gene‐specific effects. Various lines of evidence have led to the hypothesis that epigenetic changes may occur early in cancer development, leading to a polyclonal precursor of “neoplasia‐ready” cells susceptible to environmental and age‐dependent damage. Later, specific classical genetic changes in oncogenes and tumour‐suppressor genes rendered vulnerable as a result of epigenetic modification can lead to monoclonal expansion.99 In Barrett's carcinogenesis, changes in methylation status have been identified across several genes.100,101 These early epigenetic changes could arise as a result of chronic injury—for example, through reflux exposure, and would again help to explain why such exposures could be cancer promoting even when they are not inherently mutagenic. This hypothesis has not been specifically tested in the context of Barrett's adenocarcinoma; however, liver regeneration after tissue injury leads to widespread hypomethylation,102 and environmental stress titrates out HSP90, which is required to fold the SMYD3 histone H3‐K4 methyltransferase.103

Chromosomal instability is another form of genetic instability and changes in microsatellite allele sizes (DNA made up of short repetitive sequences) have been commonly observed in Barrett's oesophagus,88,104 although not at a frequency that qualifies them as “microsatellite unstable” (replication slippage occurring as a result of microsatellites as seen in hereditary non‐polyposis coli cancer). During tumour progression, widespread chromosomal losses and gains occur,105 and aneuploidy (deviation from normal diploid chromosomal number) is commonly observed late in progression.88 Whether altered chromosomal copy number represents a primary event or whether this is a secondary event occurring with uncontrolled proliferation is a question of debate and ongoing research.106

Clinical ramifications (box 3)

Biomarkers

Part of the impetus for elucidating the molecular changes occurring throughout the metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence is to identify molecular changes or biomarkers predictive for cancer development. The most promising data come from the combination of p53 and aneuploidy status from flow cytometric studies, which have shown a relative risk of 4 for progression to adenocarcinoma when a clone containing both of these abnormalities is >5 cm.88 Unfortunately, despite the identification of several molecular changes, none of these has yet been adopted in routine practice. Part of the reason for this is the paucity of molecular changes that have been validated in phase 4 studies (prospective studies that have been evaluated in large patient cohorts).107 The other reason for the lack of clinically useful biomarkers may result from the fact that cancer progression is non‐linear and results from global genetic instability and epigenetic changes. Hence, future efforts to define biomarkers may be better focused on assaying for the acquired biological properties that occur during cancer development rather than focusing on specific genes. For example, there is an increase in the proliferation marker mini‐chromosome maintenance 2 expression during the malignant progression of Barrett's oesophagus. Furthermore, in a longitudinal case–control study, mini‐chromosome maintenance 2 expression was increased before the development of dysplasia in the patients who went on to develop cancer.58 It is also hoped that new biomarkers will emerge from the systematic evaluation of changes in expression and epigenetic changes, such as methylation, across large numbers of genes.87,108,109 In the future, a systematic approach will be required to define sensitive and specific markers that are measurable using robust assays applicable to routine clinical practice.

Box 3: Clinical developments

Biomarker discovery needs to be coupled with clinical assay development.

Risk stratification using biomarkers will help determine individual patient management, such as ablation treatment, chemoprevention or molecular‐targeted treatments.

Chemoprevention requires testing in large, prospective randomised controlled trials.

Tailored therapy and chemoprevention

In the cancer specialty, marked advances have been made in identifying specific treatments as a result of knowledge of critical genetic changes, such as HER2/NEU amplification in breast cancer and ERBB2 mutations in lung cancer. However, in view of the complexity and non‐linear pathways for cancer development and progression, it is becoming clear that only a subset of patients with a given tumour type will benefit from these treatments.110 Therefore, as more targeted treatments become available they will probably need to be tailored to the molecular basis of an individual's tumour. In Barrett's oesophagus, there are several different strategies that could be taken—for example, targeting of cell signalling pathways important in the disease pathogenesis, such as MAPK, nuclear factor‐κB and COX 2. In addition, if it is proved that epigenetic changes are fundamental to the early stages of Barrett's carcinogenesis, then agents that modify the epigenome globally, such as 5‐aza‐2′‐deoxycytidine, which inhibits DNA methylation, may prove useful, and ultimately we may be able to target specific epigenetic modifications.111 However, the possible adverse consequences of such approaches should also be borne in mind. For example, global hypomethylation induced by 5‐aza‐2′‐deoxycytidine could be detrimental for transcriptional regulation. These therapeutic modalities are at the preclinical stage in Barrett's oesophagus.

To justify the treatment of patients with premalignant Barrett's oesophagus, which has an overall low rate of malignant conversion, it will be necessary to target the patients at highest risk for developing cancer, or else to use treatments that are very safe and confer general health benefits. To date, there has been considerable interest in the use of acid suppressants and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. The rationale for the use of acid suppression arises from the in vitro and ex vivo data discussed above, which suggest that acid may adversely affect cell kinetics, activate COX2 and MAPK pathways, and cause DNA damage. Thus far, the data on whether acid suppression is a useful chemopreventive strategy are conflicting.112,113,114 The use of varying acid‐suppression regimens and the lack of data from large prospective randomised trials make it difficult to evaluate their role. Laboratory and epidemiological data suggest that aspirin and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs may be chemopreventive through their inhibitory effect on COX2.115,116,117,118 A prospective study has recently suggested that people who took aspirin or non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs regularly had a substantially lower incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma and aneuploidy than those who did not take such drugs regularly.119 The AspECT chemoprevention trial in the UK is a large randomised, prospective trial that aims to discuss the role of high‐dose versus low‐dose esomeprazole (PPI) with low dose or no aspirin on the overall mortality of patients with Barrett's oesophagus.

Conclusions

Much work still needs to be done to better characterise oesophageal stem cells in terms of molecular markers and to establish experimental systems in which the control of stem cell behaviour and transdifferentiation can be investigated. It is becoming clear that there are multiple layers of control over cell fate, and that the microenvironment is important. Hence, gastro‐oesophageal refluxate seems to have several effects at the molecular level both in terms of the development and progression of Barrett's oesophagus. The refluxate may cause non‐specific DNA damage as well as being a pro‐proliferative drive in the context of genetic instability. This may set the stage for the non‐linear acquisition of biological properties conducive to cancer development. Therefore, a different conceptual framework is required, which embraces the multiple pathways to Barrett's‐associated cancer so that clinical methods to identify high‐risk people and to provide treatment take account of this individual variation in genetic changes.

Abbreviations

APC - adenomatous polyposis coli

BMDC - bone marrow‐derived stem cell

COX2 - cyclooxygenase 2

GORD - gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease

LOH - loss of heterozygosity

MAPK - mitogen‐activated protein kinase

PPI - proton pump inhibitor

TGFβ - tumour growth factor β

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Spechler S J, Goyal R J. The columnar‐lined esophagus, intestinal metaplasia and Norman Barrett. Gastroenterology 1996110614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaezi M, Richter J. Role of acid and duodenogastroesophageal reflux in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 19961111192–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaheen N, Crosby M, Bozymski E.et al Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000119333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jankowski J A, Provenzale D, Moayyedi P. Esophageal adenocarcinoma arising from Barrett's metaplasia has regional variations in the west. Gastroenterology 2002122588–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eloubeidi M A, Mason A C, Desmond R A.et al Temporal trends (1973–1997) in survival of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma in the United States: a glimmer of hope? Am J Gastroenterol 2003981627–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Soest E M, Dieleman J P, Siersema P D.et al Increasing incidence of Barrett's oesophagus in the general population. Gut 2005541062–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devesa S S, Blot W J, Fraumeni J F., Jr Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer 1998832049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El‐Serag H B, Mason A C, Petersen N.et al Epidemiological differences between adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia in the USA. Gut 200250368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong A, Fitzgerald R C. Epidemiologic risk factors for Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 200531–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T.et al Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology 20051291825–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald R C. Complex diseases in gastroenterology and hepatology: GERD, Barrett's, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20053529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casson A G, Zheng Z, Evans S C.et al Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes in the molecular pathogenesis of esophageal (Barrett) adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2005261536–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gough M D, Ackroyd R, Majeed A W.et al Prediction of malignant potential in reflux disease: are cytokine polymorphisms important? Am J Gastroenterol 20051001012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Lieshout E M, Roelofs H M, Dekker S.et al Polymorphic expression of the glutathione S‐transferase P1 gene and its susceptibility to Barrett's esophagus and esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res 199959586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pharoah P D, Dunning A M, Ponder B A.et al Association studies for finding cancer‐susceptibility genetic variants. Nat Rev Cancer 200411850–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillen P, Keeling P, Byrne P J.et al Implication of duodenogastric reflux in the pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus. Br J Surg 198875540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Walsh T N, O'Dowd G.et al Mechanisms of columnar metaplasia and squamous regeneration in experimental Barrett's esophagus. Surgery 1994115176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schier S, Wright N A. Stem cell relationships and the origin of gastrointestinal cancer. Oncology 2005699–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery R K, Mulberg A E, Grand R J. Development of the human gastrointestinal tract: twenty years of progress. Gastroenterology 1999116702–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu W Y, Slack J M, Tosh D. Conversion of columnar to stratified squamous epithelium in the developing mouse oesophagus. Dev Biol 2005284157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seery J P, Stem cells of the oesophageal epithelium J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1783–1789. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.9.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rochat A, Kobayashi K, Barrandon Y. Location of stem cells of human hair follicles by clonal analysis. Cell 1994761063–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coad R A, Woodman A C, Warner P J.et al On the histogenesis of Barrett's oesophagus and its associated squamous islands: a three‐dimensional study of their morphological relationship with native oesophageal gland ducts. J Pathol 2005206388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahnen D J, Poulsom R, Stamp G W.et al The ulceration‐associated cell lineage (UACL) reiterates the Brunner's gland differentiation programme but acquires the proliferative organization of the gastric gland. J Pathol 1994173317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulson T G, Lianjun Xu, Sanchez C.et al Neosquamous epithelium does not typically arise from Barrett's epithelium. Clin Cancer Res 2006121701–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjerkvig R, Tysnes B B, Aboody K S.et al Opinion: the origin of the cancer stem cell: current controversies and new insights. Nat Rev Cancer 20055899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houghton J, Wang T C. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a new paradigm for inflammation‐associated epithelial cancers. Gastroenterology 20051281567–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S.et al Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow‐derived cells. Science 20043061568–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosh D, Slack J M. How cells change their phenotype. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20023187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W C, Horb M E, Tosh D.et al In vitro transdifferentiation of hepatoma cells into functional pancreatic cells. Mech Dev 2005122835–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniely Y, Liao G, Dixon D.et al Critical role of p63 in the development of a normal esophageal and tracheobronchial epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2004287C171–C181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGinnis W, Krumlauf R. Homeobox genes and axial patterning. Cell 199268283–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonner C A, Loftus S K, Wasmuth J J. Isolation, characterization, and precise physical localization of human CDX1, a caudal‐type homeobox gene. Genomics 199528206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberg D G, Sullivan J, Kang E.et al Cdx2 ectopic expression induces gastric intestinal metaplasia in transgenic mice. Gastroenterology 2002122689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck F, Chawengsaksophak K, Waring P.et al Reprogramming of intestinal differentiation and intercalary regeneration in Cdx2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999967318–7323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eda A, Osawa H, Satoh K.et al Aberrant expression of CDX2 in Barrett's epithelium and inflammatory esophageal mucosa. J Gastroenterol 20033814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lord R V, Brabender J, Wickramasinghe K.et al Increased CDX2 and decreased PITX1 homeobox gene expression in Barrett's esophagus and Barrett's‐associated adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2005138924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips R W, Frierson H F, Jr, Moskaluk C A. Cdx2 as a marker of epithelial intestinal differentiation in the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2003271442–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandrasoma P T, Der R, Dalton P.et al Distribution and significance of epithelial types in columnar‐lined esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2001251188–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takito J, Al‐Awqati Q. Conversion of ES cells to columnar epithelia by hensin and to squamous epithelia by laminin. J Cell Biol 20041661093–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzgerald R, Abdalla S, Onwuegbusi B.et al Inflammatory gradient in Barrett's oesophagus: implications for disease complications. Gut 200251316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzgerald R C, Onwuegbusi B A, Bajaj‐Elliott M.et al Diversity in the oesophageal phenotypic response to gastro‐oesophageal reflux: immunological determinants. Gut 200250451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onwuegbusi B A, Aitchison A, Chin S F.et al Impaired TGFβ signalling in Barrett's carcinogenesis due to frequent SMAD4 inactivation. Gut 200655764–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunker N, Krieglstein K. Targeted mutations of transforming growth factor‐beta genes reveal important roles in mouse development and adult homeostasis. Eur J Biochem 20002676982–6988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawford S, Stellmach V, Murphy‐Ullrich J.et al Thrombospondin‐1 is a major activator of TGF‐β1 in vivo. Cell 1998931159–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong N A, Wilding J, Bartlett S.et al CDX1 is an important molecular mediator of Barrett's metaplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 20051027565–7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fein M, Fuchs K H, Stopper H.et al Duodenogastric reflux and foregut carcinogenesis: analysis of duodenal juice in a rodent model of cancer. Carcinogenesis 2000212079–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kazumori H, Ishihara S, Rumi M A.et al Bile acids directly augment caudal related homeobox gene Cdx2 expression in oesophageal keratinocytes in Barrett's epithelium. Gut 20065516–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marchetti M, Caliot E, Pringault E. Chronic acid exposure leads to activation of the cdx2 intestinal homeobox gene in a long‐term culture of mouse esophageal keratinocytes. J Cell Sci 20031161429–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Souza R F, Shewmake K, Terada L S.et al Acid exposure activates the mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathways in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 2002122299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stupack D G, Cheresh D A. Get a ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. J Cell Sci 20021153729–3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Renan M. How many mutations are required for tumorigenesis? Implications from human cancer data. Mol Carcinogen 19937139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanahan D, Weinberg R A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 200010057–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walch A K, Zitzelsberger H F, Bruch J.et al Chromosomal imbalances in Barrett's adenocarcinoma and the metaplasia‐dysplasia‐carcinoma sequence. Am J Pathol 2000156555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prevo L J, Sanchez C A, Galipeau P C.et al p53‐mutant clones and field effects in Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Res 1999594784–4787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buttar N S, Wang K K. Mechanisms of disease: carcinogenesis in Barrett's esophagus. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 20041106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wild C P, Hardie L J. Reflux, Barrett's oesophagus and adenocarcinoma: burning questions. Nat Rev Cancer 20033676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sirieix P, O'Donovan M, Brown J.et al Surface expression of mini‐chromosome maintenance proteins provides a novel method for detecting patients at risk for developing adenocarcinoma in Barrett's oesophagus. Clin Cancer Res 200392560–2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Going J J, Keith W N, Neilson L.et al Aberrant expression of minichromosome maintenance proteins 2 and 5, and Ki‐67 in dysplastic squamous oesophageal epithelium and Barrett's mucosa. Gut 200250373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lao‐Sirieix P, Brais R, Lovat L.et al Cell cycle phase abnormalities do not account for disordered proliferation in Barrett's carcinogenesis. Neoplasia 20046751–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rabinovitch P S, Longton G, Blount P L.et al Predictors of progression in Barrett's esophagus III: baseline flow cytometric variables. Am J Gastroenterol 2001963071–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bian Y S, Osterheld M C, Fontolliet C.et al p16 inactivation by methylation of the CDKN2A promoter occurs early during neoplastic progression in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 20021221113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eads C A, Lord R V, Kurumboor S K.et al Fields of aberrant CpG island hypermethylation in Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2000605021–5026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helm J, Enkemann S A, Coppola D.et al Dedifferentiation precedes invasion in the progression from Barrett's metaplasia to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2005112478–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fitzgerald R C, Omary M B, Triadafilopoulos G. Dynamic effects of acid on Barrett's esophagus: an ex vivo differentiation and proliferation model. J Clin Invest 1996982120–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fitzgerald R, Omary M, Triadafilopoulos G. Acid modulation of HT29 cell growth and differentiation: an in vitro model for Barrett's esophagus. J Cell Sci 1997110663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morgan C, Alazawi W, Sirieix P.et al In vitro acid exposure has a differential effect on apoptotic and proliferative pathways in a Barrett's adenocarcinoma cell line. Am J Gastroenterol 200499218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Putney L K, Barber D L. Na‐H exchange‐dependent increase in intracellular pH times G2/M entry and transition. J Biol Chem 200327844645–44649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaur B S, Ouatu‐Lascar R, Omary M B.et al Bile salts induce or blunt cell proliferation in Barrett's esophagus in an acid‐dependent fashion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000278G1000–G1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whittles C E, Biddlestone L R, Burton A.et al Apoptotic and proliferative activity in the neoplastic progression of Barrett's oesophagus: a comparative study. J Pathol 1999187535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dvorakova K, Payne C M, Ramsey L.et al Apoptosis resistance in Barrett's esophagus: ex vivo bioassay of live stressed tissues. Am J Gastroenterol 2005100424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parenti A, Leo G, Porzionato A.et al Expression of survivin, p53, and caspase 3 in Barrett's esophagus carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol 20063716–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raouf A A, Evoy D A, Carton E.et al Loss of Bcl‐2 expression in Barrett's dysplasia and adenocarcinoma is associated with tumor progression and worse survival but not with response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Dis Esophagus 20031617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vallbohmer D, Peters J H, Oh D.et al Survivin, a potential biomarker in the development of Barrett's adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2005138701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mahidhara R S, Queiroz De Oliveira P E, Kohout J.et al Altered trafficking of Fas and subsequent resistance to Fas‐mediated apoptosis occurs by a wild‐type p53 independent mechanism in esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Res 2005123302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reinehr R, Becker S, Wettstein M.et al Involvement of the Src family kinase yes in bile salt‐induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology 20041271540–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harris J C, Clarke P A, Awan A.et al An antiapoptotic role for gastrin and the gastrin/CCK‐2 receptor in Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Res 2004641915–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Auvinen M I, Sihvo E I, Ruohtula T.et al Incipient angiogenesis in Barrett's epithelium and lymphangiogenesis in Barrett's adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002202971–2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mobius C, Stein H J, Becker I.et al The ‘angiogenic switch' in the progression from Barrett's metaplasia to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 200329890–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mobius C, Stein H J, Spiess C.et al COX2 expression, angiogenesis, proliferation and survival in Barrett's cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 200531755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kandil H M, Tanner G, Smalley W.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 200146785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wilson K T, Fu S, Ramanujam K S.et al Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase‐2 in Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 1998582929–2934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zimmermann K C, Sarbia M, Weber A A.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res 199959198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abdalla S I, Lao‐Sirieix P, Novelli M R.et al Gastrin‐induced cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in Barrett's carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2004104784–4792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shirvani V N, Ouatu‐Luscar R, Kaur B S.et al Cyclo‐oxygenase 2 expression in Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma: ex vivo induction by bile salts and acid exposure. Gastroenterology 2000118487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Osterheld M C, Bian Y S, Bosman F T.et al Beta‐catenin expression and its association with prognostic factors in adenocarcinoma developed in Barrett esophagus. Am J Clin Pathol 2002117451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clement G, Braunschweig R, Pasquier N.et al Alterations of the Wnt signaling pathway during the neoplastic progression of Barrett's esophagus. Oncogene 2006253084–3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maley C C, Galipeau P C, Li X.et al The combination of genetic instability and clonal expansion predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2004647629–7633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olliver J R, Hardie L J, Gong Y.et al Risk factors, DNA damage, and disease progression in Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 200514620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Levine A. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 199788323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hamelin R, Flejou J F, Muzeau F.et al TP53 gene mutations and p53 protein immunoreactivity in malignant and premalignant Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 19941071012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Galipeau P C, Cowan D S, Sanchez C A.et al 17p (p53) allelic losses, 4N (G2/tetraploid) populations, and progression to aneuploidy in Barrett's esophagus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996937081–7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reid B J, Prevo L J, Galipeau P C.et al Predictors of progression in Barrett's esophagus II: baseline 17p (p53) loss of heterozygosity identifies a patient subset at increased risk for neoplastic progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2001962839–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Muzeau F, Flejou J F, Potet F.et al Profile of p53 mutations and abnormal expression of P53 protein in 2 forms of esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 199620430–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barrett M T, Sanchez C A, Prevo L J.et al Evolution of neoplastic cell lineages in Barrett oesophagus. Nat Genet 199922106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pohler E, Craig A L, Cotton J.et al The Barrett's antigen anterior gradient‐2 silences the p53 transcriptional response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Proteomics 20043534–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Williams A C, Collard T J, Paraskeva C. An acidic environment leads to p53 dependent induction of apoptosis in human adenoma and carcinoma cell lines: implications for clonal selection during colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncogene 1999183199–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Achison M, Hupp T R. Hypoxia attenuates the p53 response to cellular damage. Oncogene 2003223431–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feinberg A P, Tycko B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat Rev Cancer 20044143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schildhaus H U, Krockel I, Lippert H.et al Promoter hypermethylation of p16INK4a, E‐cadherin, O6‐MGMT, DAPK and FHIT in adenocarcinomas of the esophagus, esophagogastric junction and proximal stomach. Int J Oncol 2005261493–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eads C A, Lord R V, Wickramasinghe K.et al Epigenetic patterns in the progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2001613410–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wilson M J, Shivapurkar N, Poirier L A. Hypomethylation of hepatic nuclear DNA in rats fed with a carcinogenic methyl‐deficient diet. Biochem J 1984218987–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hamamoto R, Furukawa Y, Morita M.et al SMYD3 encodes a histone methyltransferase involved in the proliferation of cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol 20046731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meltzer S J, Yin J, Manin B.et al Microsatellite instability occurs frequently and in both diploid and aneuploid cell populations of Barrett's‐associated esophageal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 1994543379–3382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Albrecht B, Hausmann M, Zitzelsberger H.et al Array‐based comparative genomic hybridization for the detection of DNA sequence copy number changes in Barrett's adenocarcinoma. J Pathol 2004203780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nguyen H G, Ravid K. Tetraploidy/aneuploidy and stem cells in cancer promotion: the role of chromosome passenger proteins. J Cell Physiol 200620812–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pepe M S, Etzioni R, Feng Z.et al Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001931054–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kimchi E T, Posner M C, Park J O.et al Progression of Barrett's metaplasia to adenocarcinoma is associated with the suppression of the transcriptional programs of epidermal differentiation. Cancer Res 2005653146–3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mitas M, Almeida J S, Mikhitarian K.et al Accurate discrimination of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma using a quantitative three‐tiered algorithm and multimarker real‐time reverse transcription‐PCR. Clin Cancer Res 2005112205–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bell R, Verma S, Untch M.et al Maximizing clinical benefit with trastuzumab. Semin Oncol 20043135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brown R, Plumb J A. Demethylation of DNA by decitabine in cancer chemotherapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 20044501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.El‐Serag H B, Aguirre T V, Davis S.et al Proton pump inhibitors are associated with reduced incidence of dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2004991877–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carlson N, Lechago J, Richter J.et al Acid suppression therapy may not alter malignant progression in Barrett's metaplasia showing p53 protein accumulation, Am J Gastroenterol2002971340–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sagar P M, Ackroyd R, Hosie K B.et al Regression and progression of Barrett's oesophagus after antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 199582806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Oyama K, Fujimura T, Ninomiya I.et al A COX‐2 inhibitor prevents the esophageal inflammation‐metaplasia‐adenocarcinoma sequence in rats. Carcinogenesis 200526565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Farrow D C, Vaughan T L, Hansten P D.et al Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998797–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Corey K E, Schmitz S M, Shaheen N J. Does a surgical antireflux procedure decrease the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus? A meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003982390–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Buttar N S, Wang K K, Leontovich O.et al Chemoprevention of esophageal adenocarcinoma by COX‐2 inhibitors in an animal model of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 20021221101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Vaughan T L, Dong L M, Blount P L.et alNon‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and risk of neoplastic progression in Barrett's oesophagus: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol 2005;6945–952. [DOI] [PubMed]