The management of corneal perforation can be difficult. We describe a novel technique to manage corneal perforation in brittle cornea syndrome (BCS).

Case report

A 14‐year‐old daughter of consanguineous Pakistani parents presented with a history of a bottle cap having struck her left eye. She had a history of multiple trauma to both eyes since childhood.

At presentation, there was limbus‐to‐limbus corneal perforation in the left eye. The right eye had a failed corneal graft (for extensive corneal opacities). An examination under general anaesthesia showed a collapsed left eye with rolled‐in corneal edges, without any scleral injury. There was partial aniridia, aphakia and prolapsed vitreous, with no obvious retinal detachment. She was also noted to have hypermobility of the small joints of her hands, with bilateral camptodactyly of the fifth fingers and over‐riding toes.

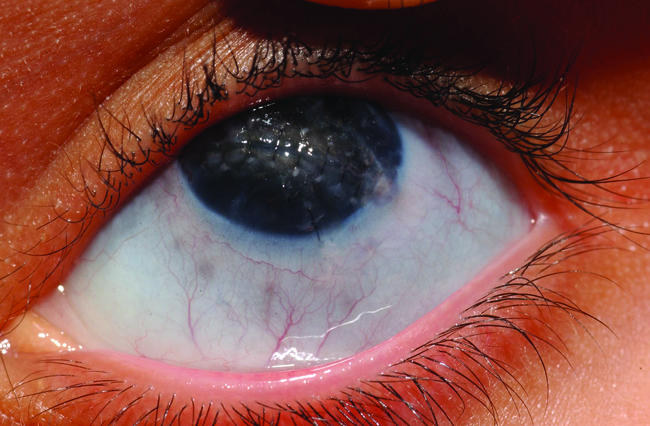

During primary repair, the cornea was noted to be soft, with cheese‐wiring of 10/0 nylon sutures. At review on past‐operative day 1, she had a flat anterior chamber, necessitating a second operation. During this operation, suture track leaks were observed with the use of fluorescein. These were successfully tamponaded with air. To allow sufficient duration of tamponade, a non‐expansile (14%) perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas exchange was performed after transcorneal three port vitrectomy to gain maximal gas fill. Postoperatively, the cornea was Siedel negative. The patient was kept supine for 10 days, at the end of which the globe remained formed (fig 1).

Figure 1 The left eye after the corneal perforation was repaired. Informed consent was received for publication of this figure.

A month later, the patient received a penetrating corneal injury to the right eye while not using her protective goggles. She underwent primary surgical repair similar to the left eye using C3F8 gas. The final visual acuity was hand movement by both eyes.

Discussion

The patient's history suggested an underlying connective tissue disorder affecting the eyes.

BCS is a generalised connective tissue disorder characterised by corneal rupture, after a minor trauma, or spontaneously.1 Other features include keratoconus or keratoglobus, blue sclera, red hair, hyperelasticity of the skin without excessive fragility, and hypermobility of the joints.2 BCS has been reported mainly in Middle Eastern consanguineous families, although no underlying genetic defect has been identified to date.3

A differential diagnosis is Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type VI, which is associated with kyphoscoliosis and thin sclera (with rupture after trivial trauma). It is characterised by the absence or mutation of the procollagen lysyl hydroxylase gene on chromosome 1, causing a deficiency of the enzyme lysyl‐hydroxylase.4 This leads to a build‐up of urinary hydroxylysyl‐pyridinoline. In contrast, BCS has normal total urinary pyridinoline ratios. The urinary test results of this patient showed a normal ratio of total lysyl‐pyridinoline to total hydroxylysyl‐pyridinoline, suggesting a diagnosis of BCS.

Repair of corneal perforations using tissue adhesives and viscoelastic agents,5 and onlay epikeratoplasty with a donor corneoscleral button to repair a ruptured keratoglobus,6 has been reported previously. Air tamponade is also commonplace, but the intraocular gas tamponade we used is a novel technique. Prolonged C3F8 gas contact with the corneal wound prevented aqueous egress, allowing sufficient wound integrity while keeping the globe formed. This is the first case report of the use of a non‐expansile volume of C3F8 gas to repair the brittle cornea in BCS, which could be generally applied to fragile leaking corneas.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of the person's details in this report.

References

- 1.Izquierdo L, Jr, Mannis M J, Marsh P B.et al Bilateral spontaneous corneal rupture in brittle cornea syndrome: a case report. Cornea 199918621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zlotogora J, BenEzra D, Cohen T.et al Syndrome of brittle cornea, blue sclera and joint hyperextensibility. Am J Med Genet 199036269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al‐Hussain H, Zeisberger S M, Huber P R.et al Brittle Cornea Syndrome and its delineation from the kyphoscoliotic type of Ehlers‐Danlos Syndrome (EDS VI). Am J Med Genet 200412428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinmann B, Royce P M, Superti‐Furga A. The Ehlers‐Danlos Syndrome. In: Royce PM, Steinmann B, eds. Connective tissue and its heritable disorders: molecular, genetic and medical aspects 2nd edn. New York: Wiley‐Liss, 2002431–523.

- 5.Hirst L W, DeJuan E. Sodium hyaluronate and tissue adhesive in treating corneal perforations. Ophthalmology 1982891250–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macsai M S, Lemley H L, Schwartz T. Management of oculus fragilis in Ehlers‐Danlos type VI. Cornea 200019104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]