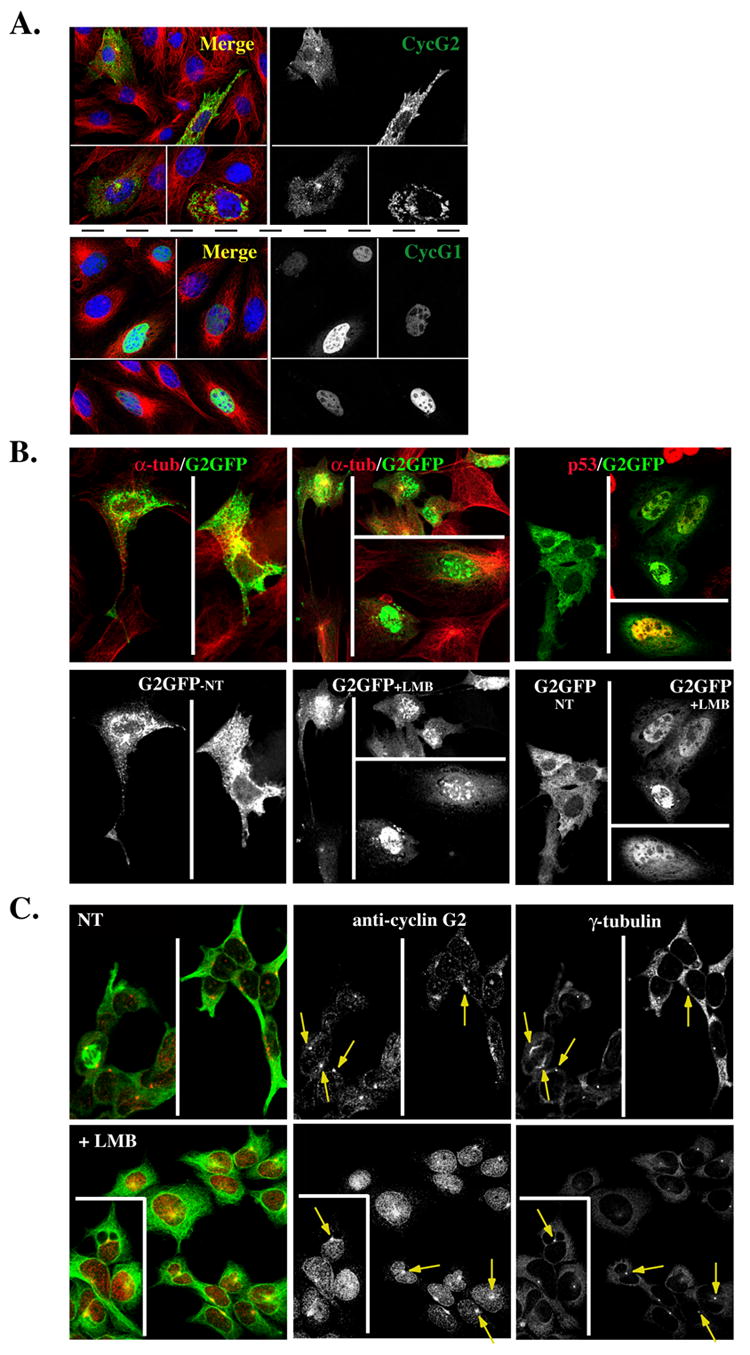

Fig. 10. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of G2.

(A) Shown are 0.3 μM confocal immunofluorescence micrographs of NIH-3T3 cells transfected with GFP-tagged cyclin G2 (top right panel) or cyclin G1 (bottom right panel), pre-extracted with Triton X-100 and fixed with methanol. The merge to the left of each panel illustrates the corresponding G2-GFP or G1GFP co-stained for α-tubulin (green) and for DNA with TOTO-3 (blue). (B) CRM1 dependent nuclear export of ectopically expressed cyclin G2. Confocal images of G2-GFP transfected NIH3T3 cells non-treated (NT) (left panels) or LMB treated (middle panels) for 9 h, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Note the accumulation of G2-GFP in the nucleus with LMB treatment. Shown above each panel in color are corresponding merge images with DM1A mouse anti-α-tubulin (red) co-staining. Far right panels show a repeat experiment of G2-GFP expressing cells NT (left field) or LMB treated for 9 h (right fields). The cells in the right fields were costained for p53 to confirm that the LMB treatment increases nuclear staining of a known CRM1 target protein. (C) Endogenous cyclin G2 accumulates in the nucleus of U2OS cells treated with Leptomycin B (LMB). Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs show NT (top panels) or 6 h LMB treated (bottom panels) cells, fixed in methanol, and stained for γ-tubulin, cyclin G2 and α-tubulin. The pseudo-colored image on the left shows a merge of cyclin G2 (red) and α-tubulin (green). Note the accumulation of cyclin G2 in the nucleus of LMB treated cells and yet the arrows point to the maintenance of centrosomal G2 in these treated cells.