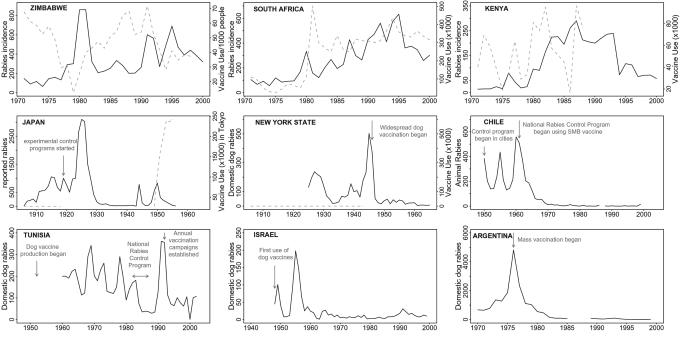

Fig. 3.

Evidence for density-dependent feedbacks between rabies incidence and vaccination responses and the impacts of reactive and proactive vaccination campaigns. Rabies cases (solid black lines) and vaccine use (dotted gray lines) are plotted for Zimbabwe, South Africa, Kenya, Japan, New York, Chile, Tunisia, Israel, and Argentina (from refs. 35, 38, 39, and 42–44). Annotated arrows indicate initiation or changes in vaccination programs. For Zimbabwe, the number of dog vaccinations delivered per 1,000 people is shown, whereas for South Africa, Kenya, and Japan, the total number of vaccines used is plotted. Across Africa, domestic dog populations have been increasing; thus vaccine use would need to increase to maintain the same coverage. The Zimbabwe data therefore provide a better approximation of vaccination coverage, although the human/dog ratio is unlikely to have remained constant over this period. Large rabies outbreaks tend to follow periods with little vaccination use, and vaccine use tends to increase after large outbreaks (rabies incidence predicts 60% of the variation in vaccine use the following year for South Africa, and vaccine use predicts 40% of the variation in incidence the following year for both Zimbabwe and South Africa; P < 0.001 in all cases). Sustained mass vaccination results in declines in domestic dog rabies as shown by the records from Japan, New York, Chile, Israel, and Argentina. There is no evidence of short cycles in Japan, New York, or Argentina before vaccines were deployed. Approximately 5-year cycles occur in Chile, Tunisia, and Israel when vaccination efforts were not uniformly applied at a national level, whereas intensification of mass vaccination controlled dog rabies.