Abstract

Comparison is a fundamental tool for analyzing DNA sequence. Interspecies sequence comparison is particularly powerful for inferring genome function and is based on the simple premise that conserved sequences are likely to be important. Thus, the comparison of a genomic sequence with its orthologous counterpart from another species is increasingly becoming an integral component of genome analysis. In ideal situations, such comparisons are performed with orthologous sequences from multiple species. To facilitate multispecies comparative sequence analysis, a robust and scalable strategy for simultaneously constructing sequence-ready bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) contig maps from targeted genomic regions has been developed. Central to this approach is the generation and utilization of “universal” oligonucleotide-based hybridization probes (“overgo” probes), which are designed from sequences that are highly conserved between distantly related species. Large collections of these probes are used en masse to screen BAC libraries from multiple species in parallel, with the isolated clones assembled into physical contig maps. To validate the effectiveness of this strategy, efforts were focused on the construction of BAC-based physical maps from multiple mammalian species (chimpanzee, baboon, cat, dog, cow, and pig). Using available human and mouse genomic sequence and a newly developed computer program (soop) to design the requisite probes, sequence-ready maps were constructed in all species for a series of targeted regions totaling ∼16 Mb in the human genome. The described approach can be used to facilitate the multispecies comparative sequencing of targeted genomic regions and can be adapted for constructing BAC contig maps in other vertebrates.

With the completion of a draft sequence of the human genome (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001; Venter et al. 2001), attention is increasingly shifting to the sequencing of other genomes. Efforts to sequence the genomes of experimental models, such as the mouse, rat, and zebrafish, are progressing rapidly (Green 2001). In addition, the sequencing of the compact genomes of two pufferfish species (Fugu rubripes and Tetraodon nigroviridis) is now well underway (Green 2001). The availability of sequence data from multiple vertebrates will provide a valuable resource for comparative sequence analysis, which has proven to be a powerful means for identifying the functional elements encoded within DNA (Hardison 2000; Miller 2000; Wasserman et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2001; Pennacchio and Rubin 2001; Touchman et al. 2001; DeSilva et al. 2002). Indeed, comparative sequencing represents a central component of the ongoing efforts to elucidate the function and evolutionary history of the human genome.

In charting a course for future genome explorations, numerous species emerge as potential candidates. However, the current cost of sequencing limits the number of vertebrates that can be sequenced comprehensively to a small handful, at least for the near future. Thus, surveying sequences from an evolutionarily diverse set of vertebrates realistically can be performed only by the targeted mapping and sequencing of smaller, well-defined genomic regions. Inevitably, this first requires isolating the region of interest in a form suitable for sequencing, which is most often accomplished by constructing contig maps of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones (The International Human Genome Mapping Consortium 2001).

Prior to the development of methods for large-scale sequencing, comparative mapping represented the primary approach for comparing the genomes of divergent species. The ability to compare genomes in a reliable fashion stems from the fact that gene linkage often is conserved to a great extent over evolutionary time, resulting in chromosomal segments (or in some cases complete chromosomes) that have the same gene content and order in diverged species (O'Brien et al. 1999). Fundamental to comparative mapping is the cross-referencing of genomic regions containing orthologous markers localized in each species. The availability of a draft human genome sequence (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001; Venter et al. 2001) has radically improved the ability to perform comparative mapping with related species. Specifically, the locations and sequences of genes in the human genome can be used to guide map construction in other species through the computational detection of orthologous sequences. This has proven to be effective for both long-range comparative mapping and the construction of sequence-ready BAC contig maps for targeted regions of interest (Thomas et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2001). For example, human genomic sequence can be used to identify orthologous mouse sequences, which in turn can be used to design small, oligonucleotide-based “overgo” probes (Vollrath 1999) for use in isolating orthologous mouse BACs. In addition, the same probes can be used to isolate clones from a closely related species, such as the rat (Summers et al. 2001).

A major limitation of the above comparative mapping approach is the requirement for an extensive DNA sequence resource for the second species, such as large collections of expressed-sequence tags (ESTs), BAC-end sequences, or whole-genome shotgun sequences. Furthermore, such an approach is not designed for the mapping of multiple species in parallel. To extend previous comparative mapping efforts (Thomas et al. 2000; Summers et al. 2001), the use of “universal” probes for constructing BAC contigs can be envisioned; such probes could be used for the simultaneous mapping of other pairs of species or even clusters of species. Indeed, universal PCR-based probes have been used for comparative mapping in mammals (Lyons et al. 1997).

To facilitate multispecies comparative mapping, a strategy that employs universal overgo-type hybridization probes for the parallel construction of sequence-ready BAC maps in multiple species has been developed. As a proof of principle, this approach has been implemented for the targeted comparative mapping of a series of regions that total ∼16 Mb in the human genome, resulting in the assembly of maps for the orthologous regions of the chimpanzee, baboon, cat, dog, cow, and pig genomes. This approach dramatically improves the number of species that can be mapped in parallel and provides a viable means for simultaneously and efficiently generating orthologous genomic sequencing templates from multiple mammals.

RESULTS

Multispecies Mapping with Universal Hybridization Probes

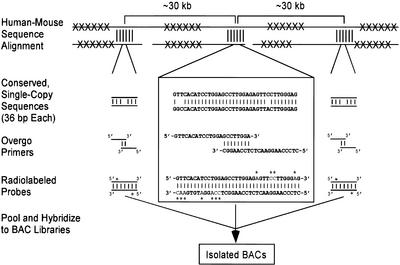

The general strategy for multispecies BAC contig construction involves the design and use of oligonucleotide-based (overgo) hybridization probes that are universal in nature, such that each probe can be used for isolating clones from multiple organisms. The approach for designing these probes is illustrated in Figure 1, as implemented for the mapping of mammalian species using probes derived from sequences conserved between human and mouse. Orthologous human (used as the reference) and mouse genomic sequence from a region of interest is masked for repetitive elements and then aligned. A set of universal overgo hybridization probes across the genomic interval is designed from regions of human-mouse sequence conservation, optimizing for physical spacing (30–40 kb) and sequence similarity. BLAST searches then are used to confirm that the sequence of each probe is truly unique in the human genome. For each overgo sequence, two overlapping oligonucleotides are generated and used in a primer-extension reaction to produce a radiolabeled, 36-bp probe. Large sets of overgo probes (upwards of 200) then are pooled and hybridized to multiple arrayed BAC libraries in parallel.

Figure 1.

Strategy for designing universal overgo hybridization probes based on human-mouse sequence alignments. Orthologous human and mouse genomic sequences are masked for repetitive elements (indicated by Xs) and then aligned. Regions with high sequence conservation (indicated by vertical lines) are identified, and a single 36-bp human sequence from each is chosen based on GC content, percent human-mouse sequence identity, and uniqueness in the human genome (see Methods). A subset of these sequences then is chosen to optimize for interprobe spacing (∼30–40 kb). Three such conserved sequences are depicted in the figure, with greater details provided (in the box) for the middle one. Overlapping pairs of oligonucleotide primers are synthesized for each sequence and used to generate double-stranded, radiolabeled (indicated by *s) probes. The probes across a target region(s) then are pooled and used to screen arrayed bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries, allowing the isolation of individual positive BACs.

To test the universal probe strategy, a series of targeted regions were mapped in six placental mammals using probes derived from human-mouse sequence alignments. Specifically, six regions of human chromosome 7 were selected based on the availability of orthologous human and mouse sequence (Table 1). These regions total ∼16 Mb (in human), range in size from ∼0.6 to ∼5.8 Mb, contain at least 124 genes, and vary in GC content (38–50%) and repeat content (39–56%). Overall, these regions are relatively gene poor compared to the average for the human genome (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001; Venter et al. 2001); however, they are representative of a large fraction of the human genome and therefore provide an appropriate test of utilizing universal hybridization probes for multispecies map construction.

Table 1.

Genomic Regions Targeted for Multispecies BAC Contig Construction

| Human Genome Location | Size (Mb) | Genes at Each End of Region | No. Known Genes | Percent GC/Repeat Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7p14 | ∼3.9 | TAXIBP1, GSBS | 22 | 42%/40% |

| 7q11 | ∼2.4 | FKBP6, ZP3A | 33 | 50%/56% |

| 7q21 | ∼5.8 | STEAP, SLC25A13 | 38 | 38%/43% |

| 7q22 | ∼0.6 | CUTL1, CAPRI | 3 | 50%/47% |

| 7q31 | ∼1.5 | CAV2, CORTBP2 | 9 | 38%/39% |

| 7q32 | ∼2.0 | AF218032, SMOH | 19 | 45%/43% |

The information presented reflects the characteristics of each region in the human genome.

Universal overgo hybridization probes were designed across these regions, at first in a semimanual fashion (n = 202) and later more automatically (n = 139) with a newly developed computer program, soop (system for optimized overgo picking; see below). In all cases, the universal probes were designed from the human sequence in ungapped human-mouse alignments (that is, alignments between human and mouse sequences devoid of insertions or deletions). In addition, a small number of probes (n = 32) were designed from human sequence that was not contained within an ungapped human-mouse alignment, primarily for isolating primate clones; these are referred as “generic” probes below. The entire collection of 373 probes were used to screen chimpanzee, baboon, cat, dog, cow, and pig BAC libraries.

Performance of Universal Hybridization Probes

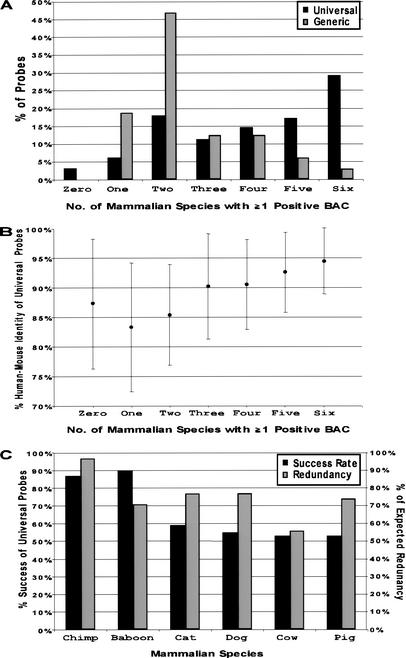

To evaluate the performance of the universal probes, the success rate of each probe was assessed for each of the BAC libraries screened. A comparison of the performance of universal (n = 341) versus generic (n = 32) probes, as measured by the number of species for which each probe successfully identified at least one positive BAC, is shown in Figure 2A. The universal probes were significantly more effective (P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) in identifying clones from multiple species (averaging 4.0 ± 1.8 species) compared to the generic probes (averaging 2.5 ± 1.3 species). Particularly illustrative was the difference between the percentage of universal versus generic probes that identified positive clones in only two of the six species (17.9% versus 46.9%, respectively) and in all six species (29.3% versus 3.2%, respectively). In addition, 89% of the probes that yielded positive clones from only one or two species were exclusively positive for the primate-derived libraries.

Figure 2.

Performance of universal overgo hybridization probes designed from human-mouse sequence alignments. A set of universal overgo hybridization probes (n = 341) was designed from orthologous human-mouse sequence alignments and used to screen six mammalian bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries. (A) The percent of the universal probes that yielded at least one positive BAC from the indicated numbers of mammalian species is indicated. In parallel, a set of generic overgo hybridization probes (n = 32) was designed from single-copy human sequences (not from human-mouse sequence alignments). The analogous performance of the generic probes for screening the same set of mammalian BAC libraries also is shown. (B) The above universal probes were grouped based on their relative performance in screening the six mammalian BAC libraries (i.e., the number of mammalian species for which at least one positive BAC was identified). The average percent human-mouse sequence identity was calculated for each group, with the indicated error bars reflecting one standard deviation from the mean. (C) The percent of the above universal probes that identified at least one positive BAC for each mammalian species is indicated. Also shown is the percent of the expected clone redundancy provided by the isolated BACs for each mammalian species, which reflects the ratio of the average redundancy obtained with the set of universal probes to the expected redundancy (as calculated for each BAC library).

The tested universal probes also were analyzed for other sequence features. No significant difference (P = 0.709, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) in success rate was observed between universal probes derived from known coding (averaging 4.0 ± 1.7 species, n = 118) versus noncoding (averaging 3.9 ± 1.9 species, n = 223) sequence. Similarly, there was no significant correlation between the success rate and the length of the ungapped human-mouse sequence alignment from which the universal probe was designed (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.066). In contrast, there was a positive correlation between success rate and the percent human-mouse sequence identity of the entire ungapped alignment (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.339) and of the 36-bp probe sequence itself (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.419); thus, the percent human-mouse sequence identity of the probe sequence is the strongest indicator of success. Figure 2B depicts the relationship between the percent human-mouse sequence identity of the universal probes and the number of species for which at least one positive BAC was identified. A general correlation can be seen between the average percent identity and the identification of clones in multiple species, especially for probes designed from sequences with >90% identity.

The performance of the universal probes varied among the six mammalian BAC libraries screened (Fig. 2C). As expected, the success rate of the universal probes was higher for the two primates (chimpanzee [87%] and baboon [90%]) compared to the other mammals (cat [59%], dog [55%], cow [53%], and pig [53%]). An unexpected result was the slightly higher success rate with baboon versus chimpanzee; this can be most likely attributed to the low clone coverage of the chimpanzee library (3.5-fold). Additionally, a subset of universal probes (n = 139) was used to screen a rat P1-derived artificial chromosome library (RPCI-31) (Woon et al. 1998); the resulting 63% success rate was similar to the average success rate (58%) achieved when the same probes were used to screen the four nonprimate mammalian BAC libraries (data not shown).

Another important measure of universal probe performance is the fraction of the expected clones successfully identified based on the estimated redundancy of each library. This value varied from 56% in cow to 97% in chimpanzee (Fig. 2C) and indicates that, while not uniform across all species, universal overgo hybridization probes are able to identify sufficiently redundant sets of clones for the assembly of sequence-ready BAC maps in multiple species.

Construction of BAC Contig Maps in Multiple Species

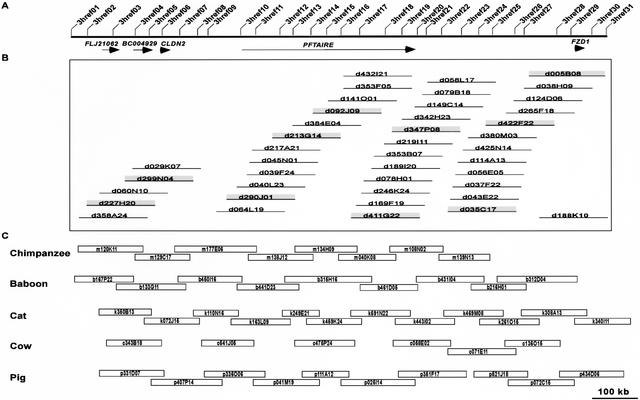

The described universal probe-based mapping strategy has been devised to compensate for the fact that not all probes will be successful in isolating clones from all species. Specifically, probes are designed at regular intervals across a genomic region such that a given BAC has the strong potential to be positive for at least two probes. The initial set of 341 universal probes had an average interprobe spacing of ∼47 kb (with the average BAC sizes for the libraries being screened ranging from ∼130 to ∼175 kb). As a result, extensive BAC contig maps should be readily assembled, even in species for which the probe success rates were <60%. This is illustrated in Figure 3, which highlights the results of multispecies comparative mapping of a ∼1.2-Mb interval of human chromosome 7q. The design and use of 31 universal probes (Fig. 3A) yielded substantial clone coverage across the orthologous region in each of the six mammals tested. The complete contig map for the orthologous region of the dog genome is shown in Figure 3B; this map provided sufficient depth of coverage for selecting minimal overlapping clones across the region for sequencing. Similar sequence-tiling paths were selected from the BAC contigs assembled for the orthologous regions of the chimpanzee, baboon, cat, cow, and pig genomes, as shown in Figure 3C.

Figure 3.

Orthologous sequence-ready bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) contig maps constructed in multiple species. (A) Comparative BAC-based physical mapping was performed on a ∼1.2-Mb interval of human chromosome 7q21 containing the indicated five genes. In this region, 31 universal overgo hybridization probes were designed from human-mouse sequence alignments, with their locations shown to scale. The set of universal probes were used to screen six mammalian BAC libraries, with both probe-content maps and restriction enzyme digest-based fingerprint maps then deduced with the isolated clones. (B) The complete dog BAC contig map constructed for this region is depicted (but not drawn to scale). From this contig map, a minimally overlapping set of BACs (i.e., a sequence-tiling path) was selected (indicated by the shaded clones). (C) The resulting sequence-tiling paths selected from the chimpanzee, baboon, cat, cow, and pig BAC contig maps are shown, with the BACs drawn to scale based on the estimated clone overlaps and sizes.

The results depicted in Figure 3 are fairly representative of the experience to date with multispecies mapping of the targets listed in Table 1. Assuming that roughly eight BACs are required to span each ∼1 Mb of orthologous sequence, then the current clone coverage for the six species across the ∼16 Mb of targeted DNA is as follows: chimpanzee (80%, 104 clones), baboon (91%, 118 clones), cat (84%, 109 clones), dog (70%, 91 clones), cow (64%, 83 clones), and pig (77%, 100 clones). While complete clone continuity is not always achieved following one round of library screening, the initial clone maps routinely assembled at this stage (e.g., those depicted in Fig. 3) are sufficient to localize the gaps. Subsequent clone-end walking typically is minimal and usually yields fully contiguous sequence-tiling paths.

Validating Orthology of BACs Isolated with Universal Hybridization Probes

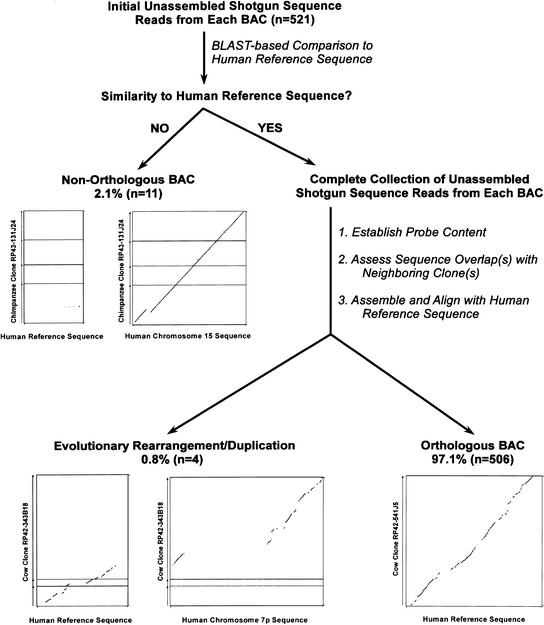

A critical issue relating to the universal probe-based mapping strategy detailed above is the reliability of isolating BACs from orthologous (as opposed to nonorthologous) genomic regions. Preliminary sequence data now have been generated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Sequencing Center (see www.nisc.nih.gov) for 521 BACs isolated from the six mammalian species using universal probes designed from the genomic regions listed in Table 1. This has provided the opportunity to evaluate in a rigorous fashion the orthology of a large number of isolated BACs and, therefore, the general specificity of our multispecies mapping approach.

Our standard routine for validating orthology of an isolated BAC is illustrated in Figure 4. First, an initial set of unassembled shotgun sequence reads from the clone is compared to the expected human reference sequence. If significant similarity is seen, the BAC is presumed to be orthologous; otherwise, it is presumed to be nonorthologous. For the latter situations, more detailed analysis inevitably reveals significant similarity with another genomic region. For example, of the 521 isolated BACs analyzed to date, 11 (2.1%) have been classified as nonorthologous; all but one of these 11 BACs represented the first, last, or only clone in a sequence-tiling path derived from a BAC contig. Shown in Figure 4 is a dot-plot analysis of the sequence generated from one such nonorthologous BAC; significant similarity is not detected with the expected human reference sequence but is seen with the true orthologous sequence from human chromosome 15. In this case, the isolated chimpanzee BAC, which was thought to be orthologous to a segment of human chromosome 7q31 containing the CAPZA2 gene, was actually derived from a segment containing a CAPZA2 pseudogene.

Figure 4.

Process for validating orthology of bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) isolated with universal overgo hybridization probes. Initial unassembled shotgun sequence data (typically 96–384 sequence reads) generated from each BAC within a sequence-tiling path (see Fig. 3) are compared by BLAST to the corresponding human reference sequence. Each BLAST output is evaluated manually to determine whether or not there is significant similarity between the BAC and the human reference sequence (i.e., evidence of multiple independent alignments in the expected locations within the reference sequence). Clones with no significant sequence similarity are classified as nonorthologous, and this classification is confirmed by detecting similarity with another region of the human genome. For illustrative purposes, the results of analyzing the assembled sequence of a nonorthologous clone are shown (middle left). Specifically, dot-plot alignments (generated using PipMaker) are shown between the sequence of chimpanzee BAC RP43–131J24 (GenBank AC087736; 172,676 bp) and the nonorthologous human reference sequence from chromosome 7q31 (80,001 bp) as well as the orthologous human chromosome 15 sequence (186,001 bp). For each BAC initially showing significant similarity with the human reference sequence, the complete collection of unassembled shotgun sequence reads are subjected to the following steps: (1) establish the presence of the expected overgo probes (i.e., those used during clone isolation and mapping); (2) assess that the appropriate sequence overlap(s) exist with any available neighboring clone(s); and (3) assemble the BAC sequence and align it with the human reference sequence. From these analyses, clones are either classified as being orthologous (bottom right) or containing an evolutionary rearrangement and/or a duplication (bottom left). As an illustration of the latter classification, dot-plot alignments are shown between the sequence of cow BAC RP42–343B18 (GenBank AC110663; 168,542 bp) and the human reference sequence from chromosome 7q21 (70,001 bp) as well as another sequence from chromosome 7p12 (260,001 bp). These alignments reveal that separate portions of this clone are orthologous to two distinct regions on human chromosome 7, indicating that the BAC spans an evolutionary rearrangement. In analyzing 521 isolated BACs by the steps depicted in this figure, 506 clones (97.1%) were found to be orthologous to the expected human reference sequence. To illustrate the typical results obtained with an orthologous clone, a dot-plot alignment is shown between the sequence of cow BAC RP42–541J5 (GenBank AC109796; 126,126 bp) and the expected human reference sequence (120,001 bp). Note that the dot-plots in this figure are not drawn to scale.

All presumed orthologous BACs are subjected to additional analyses once a more complete collection of sequence reads (typically sufficient to produce draft or full-shotgun assembled sequence) becomes available. Specifically, the sequence reads for each clone are examined to verify the presence of the expected overgo probes and to confirm appropriate overlaps with neighboring clones. In addition, the sequence for each BAC is assembled and aligned to the corresponding human reference sequence using PipMaker, and the resulting alignments are examined manually. Following these analyses, four of the 521 BACs (0.8%) have been found to contain sequence that only partially aligns to the human reference sequence. These clones cannot be classified simply as orthologous or nonorthologous as they contain genomic segments that have undergone some evolutionary change(s), such as a complex rearrangement and/or a duplication. An example of this is shown in Figure 4, where an isolated cow BAC (the first clone depicted in Fig. 3C) was found to contain distinct portions that were orthologous to two regions on human chromosome 7, the expected segment on chromosome 7q21 and a second segment on chromosome 7p12. Formally, this result could reflect a chimeric clone; however, the presence of each restriction fragment from the sequenced clone in multiple overlapping BACs makes this possibility unlikely. Dot-plot analysis indicates that this clone spans a region that has undergone an evolutionary rearrangement. Each of the other three BACs in this category was found to contain a duplicated segment that is present in more than one location in the human genome, including the targeted genomic region. Of note, more subtle, local rearrangements within the sequenced BACs could not be fully detected without finished sequence; therefore, these were not routinely cataloged as part of our clone validation studies.

Based on the analyses illustrated in Figure 4, 506 of the 521 BACs (97.1%) have been found to be orthologous to the expected genomic region based on detecting sequence similarity between the entire clone insert and the human reference sequence. As a representative example, a dot-plot alignment between an orthologous BAC sequence (the second cow clone depicted in Fig. 3C) and its corresponding human reference sequence is shown in Figure 4. Together, these data indicate that our strategy for multispecies BAC isolation and mapping using universal overgo probes reliably yields clones from the appropriate orthologous regions of the six mammalian species examined here.

Systematic Design of Universal Hybridization Probes

Utilizing the key criteria established by the above experience in multispecies comparative mapping, a computer program (soop) was developed that provides an automated and robust method for designing universal overgo hybridization probes. Indeed, 139 of the universal probes used for the mapping studies described above were designed by soop.

As a further test, soop was used to design universal probes across the entire ∼16 Mb of targeted genomic regions listed in Table 1 using the available BAC-derived human and mouse sequences. Overall, soop was able to design probes with an average human-mouse sequence identity of 95.8% and average interprobe spacing of 31 kb. This is notably better than the efforts that employed a semimanual approach for probe design (which yielded probes with an average human-mouse sequence identity of 91% and an average interprobe spacing of 47 kb).

These results indicate that soop will be useful for designing universal probes from any region of the human genome for which orthologous mouse sequence is available. However, at this time only a fraction of the mouse genome is available as BAC-derived sequence. A more extensive but fragmentary data set of mouse sequence has been generated by whole-genome shotgun sequencing (Green 2001; Rogers and Bradley 2001). In addition, mouse whole-genome shotgun sequence can be aligned to the human genome (e.g., see genome.ucsc.edu and www.ensembl.org).

To test the potential of using mouse whole-genome shotgun sequence data for designing universal probes with soop, mouse sequence reads aligning to the targeted ∼16 Mb of human sequence (Table 1) were downloaded from Ensembl (www.ensembl.org), masked for repetitive elements, and aligned by BLAST to the human sequence. soop was used to design universal probes from the resulting human-mouse alignments (in this case, from the mouse sequence). The candidate probes were compared to the available BAC-derived mouse sequences. Roughly 25% of the probes failed to match the BAC-derived sequences and thus were presumed to be nonorthologous and discarded. The remaining probes had an average human-mouse sequence identity of 96.0% and an average interprobe spacing of 40 kb. Comparison of the universal probes designed from the two sources of mouse sequence revealed that 68% of the probes derived from the whole-genome shotgun sequence reads had an equivalent probe (based on an overlapping location within the parent alignment) in the BAC-derived population. Conversely, 53% of the BAC-derived probes had an equivalent probe in the population derived from the whole-genome shotgun sequence reads. These results indicate that the described approach for universal probe design and multispecies BAC mapping should be applicable to virtually the entire human genome using human and mouse genomic sequence data that now are readily available.

DISCUSSION

Comparative sequence analysis is an established approach for deciphering the function and evolution of genomic sequence. In this paper, a method was described for the parallel construction of targeted, orthologous, sequence-ready BAC contig maps from multiple species. This strategy involves designing universal probes from conserved sequences and utilizing them for hybridization-based screening of arrayed BAC libraries. Such mapping efforts yield both comparative physical maps and the actual templates (i.e., mapped BACs) that can be used for sequencing the corresponding regions. Most important, the described strategy offers the means to perform comparative sequencing of targeted genomic regions in a phylogenetically diverse manner.

The use of evolutionarily conserved sequences for designing universal-type markers has been described (Lyons et al. 1997). In this previous study, universal PCR assays were developed for use in constructing low-resolution comparative maps by radiation-hybrid and/or genetic mapping methods. The approach described here aims to generate high-resolution, clone-based physical maps of targeted genomic regions, which in turn can be used for multispecies comparative sequencing. These different methods are complementary, while each is associated with practical limitations when applied to multiple species. Radiation-hybrid and genetic mapping methods require panels of radiation-hybrid cell lines and genetically backcrossed animals, respectively; a clone-based mapping strategy requires genomic (i.e., BAC) libraries, which at present are available for a limited number of vertebrates.

In testing a universal probe-based mapping strategy, the performance of probes designed from regions of human-mouse sequence conservation was measured by assessing their ability to identify positive BACs derived from two primates (chimpanzee and baboon), two carnivores (cat and dog), and two artiodactyls (cow and pig). These analyses revealed that the most important factor impacting universal probe performance was the percent human-mouse sequence identity within the 36-bp probe sequence. In contrast, the use of conserved coding versus noncoding sequence had no impact on probe performance. In fact, most of the universal probes utilized to date were designed from conserved noncoding sequences, consistent with the notion that a large fraction of human-mouse conserved sequences do not correspond to coding exons (Dehal et al. 2001; Frazer et al. 2001). Thus, for the purposes of long-range comparative mapping, sequence conservation (and not gene density) appears to be the key factor in the design of universal probes.

The mapping method described here has other virtues, especially with respect to efficiency and scalability. For example, only one set of hybridization and washing conditions is needed for all probes and species, allowing for high-throughput, batch screening of BAC libraries. It also is cost effective in that major economies-of-scale are gained by the use of universal probes, especially compared to the alternative of developing and using species-specific probes for each new BAC library. For example, the mapping efforts reported here using universal probes were associated with a many-fold savings with respect to oligonucleotide synthesis and probe-labeling reactions. Even greater savings can be realized as the number of species mapped in parallel is increased.

The experience to date indicates that universal probes can be used for generating suitable sequence-ready BAC contig maps. The clone coverage provided across the targeted ∼16 Mb after a single round of BAC-library screening ranged from 64 to 91% for the six mammalian species, and this correlated with the universal probe success rate for each species. Based solely on probe-content information and restriction enzyme digest-based fingerprint analysis, it is not possible to confirm that each resulting contig map truly corresponds to the orthologous genomic region. However, shotgun sequence data have been generated for >85% of the BACs isolated from the genomic regions listed in Table 1 (see www.nisc.nih.gov), and analysis of that sequence indicates that >97% of all clones selected for sequencing indeed represent the orthologous genomic region in the species of origin (see Fig. 4). As with other physical mapping methods, duplicated chromosomal segments complicate the initial map assembly and definitive orthology assignments. However, this does not significantly diminish the utility of this strategy for the great majority of the genome.

To automate and standardize the design of universal overgo hybridization probes, the computer program soop was developed. soop designs universal probes across a region of interest using available interspecies sequence alignments, optimizing for interprobe spacing and percent sequence identity. The resulting universal probes have been found to be effective for constructing sequence-ready BAC contigs in multiple species. Importantly, soop can be used with any sets of aligned sequences. For example, soop can design universal probes using alignments derived from the existing assembled sequence of the human genome and the available mouse whole-genome shotgun sequence reads or initial assemblies. Compared to using assembled, BAC-derived mouse genomic sequence, prealigned mouse whole-genome shotgun sequence reads yielded a comparable number and quality of universal probes. Thus, with a minor modification (i.e., an additional filtering step to remove mouse sequences that align to more than one site in the human genome) and the existing human and mouse sequence resources, soop can be readily used to develop universal probes for mapping virtually any region of a mammalian genome.

Importantly, the multispecies comparative mapping strategy reported here is not limited to the set of mammals thus far studied or to the two sources of genomic sequence (human and mouse) utilized to date for universal probe design. Rather, the approach can be readily generalized to a wider evolutionary spectrum of animals through the use of other sources of genomic sequence. Already, whole-genome sequencing is well underway for the rat, zebrafish, and two pufferfish species. Such efforts will provide the opportunity to design universal probes from different pairwise alignments of different sequence data sets. The resulting probes should allow the isolation and mapping of BACs from species across wide taxonomic spans, although future efforts will need to determine how best to design such probes using different sequences. One could envision the establishment of a small number of genome-wide sets of univeral probes, with each set being appropriate for use with specific groups of species at defined evolutionary positions. Comparative mapping and sequencing done in this fashion thus can become a self-perpetuating process, in which all new sequence provides information for designing additional probes and exploring new genomes. In the long run, such a renewable and continuous production of targeted genomic sequence from multiple species will be invaluable for studying genome function and evolution.

METHODS

Design of Universal Hybridization Probes

“Overgo” hybridization probes are radioactively labeled, 36-bp, double-stranded DNA probes that are highly specific and well suited for screening arrayed BAC libraries. These probes are generated by annealing two 22mer oligonucleotides that overlap at their 3′ ends by eight complementary nucleotides and performing a primer-extension reaction with Klenow in the presence of [α32P]dATP and [α32P]dCTP, as described (Vollrath 1999) (www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc/overgo/overgo.html).

“Universal” overgo hybridization probes for screening mammalian BAC libraries were designed as follows. Orthologous human and mouse genomic sequences were masked for repetitive elements with RepeatMasker (A.F.A. Smit and P. Green, unpubl.; www.geospiza.com/products/tools/repeatmasker.html) and aligned with PipMaker (Schwartz et al. 2000) or BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997). The resulting alignment files were analyzed for regions of high similarity. The human genomic sequence was generated at the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center (www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc) and the University of Washington Genome Center (www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC). The mouse BAC-derived genomic sequence was generated at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (www.nisc.nih.gov), while the mouse whole-genome shotgun sequence was downloaded from Ensembl (www.ensembl.org).

For the studies reported here, an initial set of 202 universal overgo probes were designed semimanually. Once sufficient insight was available regarding optimal design criteria, a computer program, soop (system for optimized overgo picking; available at genome.nhgri.nih.gov/soop), was developed for designing a series of universal overgo probes across a region of interest. The routine performed by soop is as follows. Each ungapped human-mouse sequence alignment is analyzed, and a single optimal 36-bp human sequence is identified based on local similarity (≥80% identity, optimum = 100%) and suitability for oligonucleotide design (e.g., 44–56% GC content, optimum = 50%) (Vollrath 1999) (www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc/overgo/overgo.html). A subset of the optimal 36-bp sequences is selected for generating overgo probes based on spacing across the genomic region of interest, aiming for an interprobe spacing of 30–40 kb (with a minimum of 15 kb). The sequences selected by soop are compared to all available human genomic sequence by BLAST to confirm that each is unique in the genome. Finally, two oligonucleotide primers are synthesized from each 36-bp sequence and used to generate overgo probes. A total of 139 overgo probes were designed by soop and used in the studies reported here. Details about all of the universal overgo probes generated for constructing the maps reported here are available at genome.nhgri.nih.gov/soop.

BAC Library Screening and Contig Assembly

BAC libraries were screened by a single set of hybridization and washing conditions, as described (Summers et al. 2001). Filters containing arrayed clones from the following BAC libraries were obtained from the BACPAC Resource (www.chori.org/bacpac): chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes, RPCI-43, 3.5-fold coverage), baboon (Papio cynocephalus anubis, RPCI-41, 10.4-fold coverage), cat (Felis catus, RPCI-86, 10.6-fold coverage), dog (Canis familiaris, RPCI-81, 8.1-fold coverage [Li et al. 1999]), cow (Bos taurus, RPCI-42, 11.9-fold coverage [Warren et al. 2000]), and pig (Sus scrofa, RPCI-44, 10.2-fold coverage [Fahrenkrug et al. 2001]). Primary and secondary hybridization data were generated and analyzed with the program ComboScreen (Jamison et al. 2000). In primary screens where significantly more positive clones were encountered than expected, only those with the strongest hybridization signals were selected. Positive clones were subjected to restriction enzyme digest-based fingerprint analysis (Marra et al. 1997), with the resulting data processed with Image (www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Image) and FPC (Soderlund et al. 1997, 2000) (www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/fpc). Probe-content maps were constructed with Segmap (Green and Green 1991) (www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC/analysistools/segmap.cfm), and the clone-overgo information was imported into FPC. The resulting contigs were examined manually, and minimally overlapping sets of clones (sequence-tiling paths) were selected based on the fingerprint and overgo-content data. Updated sequence-tiling paths can be viewed at www.nisc.nih.gov.

WEB SITE REFERENCES

genome.nhgri.nih.gov/soop; web site for computer program, soop.

genome.ucsc.edu; UCSC Human Resource Browser.

www.chori.org/bacpac; BACPAC genome web site.

www.ensembl.org; Ensembl database web site.

www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc/overgo/overgo.html; web site for general overgo design program.

www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc; Washington University Genome Sequencing Center.

www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC; University of Washington Genome Center.

www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC/analysistools/segmap.cfm; web site for Segmap program.

www.geospiza.com/products/tools/repeatmasker.html; web site for RepeatMasker.

www.nisc.nih.gov; National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Sequencing Center.

www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Image; web site for Image program. and www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/fpc; web site for FPC program.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Elliott Margulies and Bill Murphy for critical review of this manuscript and Pieter de Jong for BAC library construction and access.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL egreen@nhgri.nih.gov; FAX (301) 402–4735.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.283202.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Bouck JB, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA. Comparing vertebrate whole-genome shotgun reads to the human genome. Genome Res. 2001;11:1807–1816. doi: 10.1101/gr.203601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P, Predki P, Olsen AS, Kobayashi A, Folta P, Lucas S, Land M, Terry A, Ecale Zhou CL, Rash S, et al. Human chromosome 19 and related regions in mouse: Conservative and lineage-specific evolution. Science. 2001;293:104–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva U, Elnitski L, Idol JR, Doyle JL, Gan W, Thomas JW, Schwartz S, Dietrich NL, Beckstrom-Sternberg SM, McDowell JC, et al. Generation and comparative analysis of ∼3.3 Mb of mouse genomic sequence orthologous to the region of human chromosome 7q11.23 implicated in Williams syndrome. Genome Res. 2002;12:3–15. doi: 10.1101/gr.214802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug SC, Rohrer GA, Freking BA, Smith TP, Osoegawa K, Shu CL, Catanese JJ, de Jong PJ. A porcine BAC library with tenfold genome coverage: A resource for physical and genetic map integration. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:472–474. doi: 10.1007/s003350020015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Sheehan JB, Stokowski RP, Chen X, Hosseini R, Cheng J-F, Fodor SPA, Cox DR, Patil N. Evolutionarily conserved sequences on human chromosome 21. Genome Res. 2001;11:1651–1659. doi: 10.1101/gr.198201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ED. Strategies for the systematic sequencing of complex genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:573–583. doi: 10.1038/35084503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ED, Green P. Sequence-tagged site (STS) content mapping of human chromosomes: Theoretical considerations and early experiences. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:77–90. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison RC. Conserved noncoding sequences are reliable guides to regulatory elements. Trends Genet. 2000;16:369–372. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison DC, Thomas JW, Green ED. ComboScreen facilitates the multiplex hybridization-based screening of high-density clone arrays. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:678–684. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Gordon L, Dehal P, Badri H, Christensen M, Grosa M, Ha C, Hammond S, Vargas M, Wehri E, et al. Homology-driven assembly of a sequence-ready mouse BAC contig map spanning regions related to the 46-Mb gene-rich euchromatic segments of human chromosome 19. Genomics. 2001;74:129–141. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Mignot E, Faraco J, Kadotani H, Cantanese J, Zhao B, Lin X, Hinton L, Ostrander EA, Patterson DF, et al. Construction and characterization of an eightfold redundant dog genomic bacterial artificial chromosome library. Genomics. 1999;58:9–17. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons LA, Laughlin TF, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Womack JE, O'Brien SJ. Comparative anchor tagged sequences (CATS) for integrative mapping of mammalian genomes. Nat Genet. 1997;15:47–56. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra MA, Kucaba TA, Dietrich NL, Green ED, Brownstein B, Wilson RK, McDonald KM, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Waterston RH. High throughput fingerprint analysis of large-insert clones. Genome Res. 1997;7:1072–1084. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. So many genomes, so little time. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:148–149. doi: 10.1038/72588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien SJ, Menotti-Raymond M, Murphy WJ, Nash WG, Wienberg J, Stanyon R, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Womack JE, Marshall Graves JA. The promise of comparative genomics in mammals. Science. 1999;286:458–481. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio LA, Rubin EM. Genomic strategies to identify mammalian regulatory sequences. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:100–109. doi: 10.1038/35052548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Bradley A. The mouse genome sequence: Status and prospects. Genomics. 2001;77:117–118. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Zhang Z, Frazer KA, Smit A, Riemer C, Bouck J, Gibbs R, Hardison R, Miller W. PipMaker—A web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome Res. 2000;10:577–586. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund C, Longden I, Mott R. FPC: A system for building contigs from restriction fingerprinted clones. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:523–535. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund C, Humphray S, Dunham A, French L. Contigs built with fingerprints, markers, and FPC V4.7. Genome Res. 2000;10:1772–1787. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1375r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers TJ, Thomas JW, Lee-Lin S-Q, Maduro VVB, Idol JR, Green ED. Comparative physical mapping of targeted regions of the rat genome. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:508–512. doi: 10.1007/s003350020021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Human Genome Mapping Consortium. A physical map of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:934–941. doi: 10.1038/35057157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JW, Summers TJ, Lee-Lin S-Q, Braden Maduro VV, Idol JR, Mastrian SD, Ryan JF, Jamison DC, Green ED. Comparative genome mapping in the sequence-based era: Early experience with human chromosome 7. Genome Res. 2000;10:624–633. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.5.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchman JW, Dehejia A, Chiba-Falek O, Cabin DE, Schwartz JR, Orrison BM, Polymeropoulos MH, Nussbaum RL. Human and mouse α-synuclein genes: Comparative genomic sequence analysis and identification of a novel gene regulatory element. Genome Res. 2001;11:78–86. doi: 10.1101/gr.165801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath D. DNA markers for physical mapping. In: Birren B, et al., editors. Genome analysis: A laboratory manual. Vol. 4 Mapping genomes. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1999. pp. 187–215. [Google Scholar]

- Warren W, Smith TP, Rexroad CE, 3rd, Fahrenkrug SC, Allison T, Shu CL, Catanese J, de Jong PJ. Construction and characterization of a new bovine bacterial artificial chromosome library with 10 genome-equivalent coverage. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:662–663. doi: 10.1007/s003350010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman WW, Palumbo M, Thompson W, Fickett JW, Lawrence CE. Human-mouse genome comparisons to locate regulatory sites. Nature Genet. 2000;26:225–228. doi: 10.1038/79965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woon PY, Osoegawa K, Kaisaki PJ, Zhao B, Catanese JJ, Gauguier D, Cox R, Levy ER, Lathrop GM, Monaco AP, et al. Construction and characterization of a 10-fold genome equivalent rat P1-derived artificial chromosome library. Genomics. 1998;50:306–316. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]