LATINOS IN THE UNITED STATES continue to be disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic. North Carolina has one of the fastest-growing Latino communities in the United States and carries a disproportionate HIV infection burden.1,2 Nine recently arrived, monolingual (Spanish-speaking), immigrant Latino men in Winston-Salem, NC, used photovoice to explore HIV prevention within their communities.

Photovoice, a qualitative and exploratory methodology founded on the principles of constructivism, empowerment education, and documentary photography, enables participants to record and reflect on the strengths and concerns of their community through photographic images and group discussion.3–7 Photovoice involves a series of steps that include determining photo assignments through consensus, distributing cameras and providing instruction on camera use, and discussing selected photographs with root-cause questioning and discussion, a technique derived from the work of Paulo Freire, in which individuals and communities dig deeply into a problem to understand the frundamental causes of that problem.8 The questions used to trigger discussion were (1) What do you see in this photograph? (2) How does this photograph make you feel? (3) What do you think about this? and (4) What can we do collectively?

The Latino immigrants, who were aged 18 to 29 years, took photographs for 4 cycles, convening after each cycle to discuss the photographs and determine the next photo assignment.

Image 1 ▶, a photograph of condoms placed on a map of North Carolina, initiated a discussion about community-driven approaches to HIV prevention. The men described the need for information and access to resources, including condoms and Spanish-language HIV counseling and testing services. They also focused on the potential to harness informal social networks within their communities. As one man commented during a photo discussion, “We should be talking to our sons, to our daughters, our nephews, our brothers and sisters. Hand out a condom and tell someone you know how to use it.”

Image 1—

“We need to be talking about condom use with everyone we know.”

Image 2 ▶ was of a Latino nightclub. The men identified Latino nightclubs as a potentially effective and untapped setting to reach Latinos and raise awareness about HIV transmission and prevention. As one man shared, “I am talking about a thousand men right there. We need information to be safe, but I have never seen any information or even a condom there. It doesn’t have to be that way.”

Image 2—

“Where many Latinos can be found on Friday and Saturday nights.”

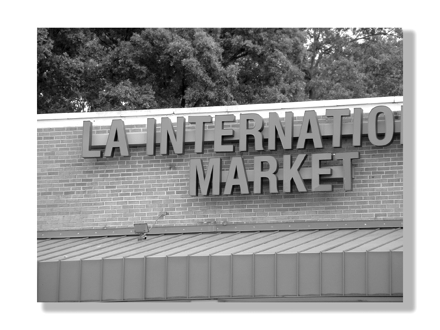

Image 3 ▶ was given the caption, “Tiendas [small Latino groceries] are a place that we all turn to, especially newcomers.” It was noted that Latino men rely on local tiendas because they sell food, medicines, and other products that are sold in their countries of origin; offer services to send money to their families in their countries of origin; and serve as a meeting place. One of the men wondered, “Why doesn’t [name of local tienda] have information about settling into life here, like how to access medical services? They could be trained about [accessing] the health clinic and share with their customers, other Latinos like us.”

Image 3—

“Tiendas are a place that we all turn to, especially newcomers.”

After a quarter of a century of the HIV epidemic, building on existing community strengths may be key to reducing the burden within communities disproportionately affected. Innovative public health strategies that are community generated and build on local assets must be supported, developed, and evaluated. As one of the men noted, “We help each other get a [US] driver’s license. We help each other go through the steps. Now we must help each other learn the steps to prevent HIV.”

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Forsyth County United Way and Wake Forest University School of Medicine Venture Funds and the Adam Foundation Inc of Winston-Salem, NC. The authors thank members of the local HIV community–university partnership in central North Carolina for their ongoing support and guidance.

Human Participant Protection Human subject protection oversight was provided by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board.

Contributors S. D. Rhodes was the principal investigator; oversaw the project; supervised data collection, analysis, and interpretation; and drafted and finalized the article. K. C. Hergenrather provided technical support during all phases of the project and contributed to drafting and finalizing the article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Vol. 16. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005.

- 2.US Census Bureau. 2005 American Community Survey Data Profile Highlights: North Carolina Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; 2005.

- 3.Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Clark G. Windows to Work: exploring employment-seeking behaviors of persons with HIV/AIDS through photovoice. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18: 243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilken A, Jolly C. Visions and Voices: indigent persons living with HIV in the southern US use photovoice to create knowledge, develop partnerships, and take action. Health Prom Pract. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Wang CC, Morrel-Samuels S, Hutchison PM, Bell L, Pestronk RM. Flint Photovoice: community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:911–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Educ Q. 1994;21: 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder; 1970.