Abstract

Care provided by specialist nurses has been shown to improve outcomes for patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), significantly reducing the number of unplanned readmissions, length of hospital stay, hospital costs, and mortality. Most patients develop CHF as a result of coronary artery disease. Once cardiac damage has occurred, the risk of developing heart failure can be reduced by providing appropriate treatment at appropriate dosages. While cardiac rehabilitation clinics provide an opportunity to check drug usage, their prime focus is on optimising patients' physical well being following a heart attack. In addition, evidence suggests that general practitioners are frequently reluctant to initiate appropriate treatments and to up-titrate drug dosages even for patients with diagnosed heart failure. Therefore, to ensure that these patients are not left on starting doses of medications many hospitals are now setting up nurse led post-myocardial infarction (MI) clinics. The Omada programme is a secondary care based, nurse led model of care set up in 1999 to improve the management of CHF by providing appropriate patient education within a nurse led clinic setting, optimising evidence based medication and fostering partnership between health professionals in both primary and secondary care. The model of care is highly applicable to the post-MI setting, where it can ensure that patients receive better care at an earlier stage.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (62.0 KB).

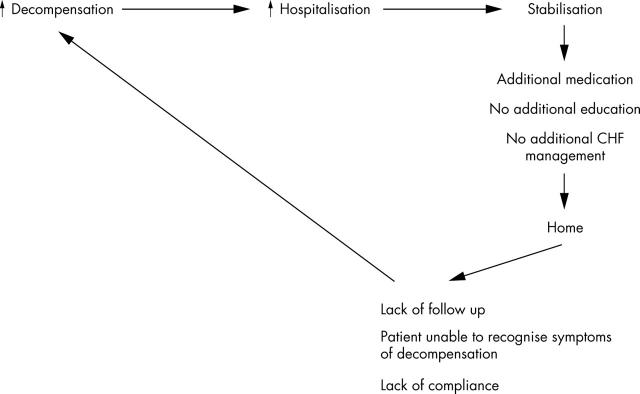

Figure 1.

The vicious cycle of repeat hospitalisation that may occur with the traditional approach to heart failure management.

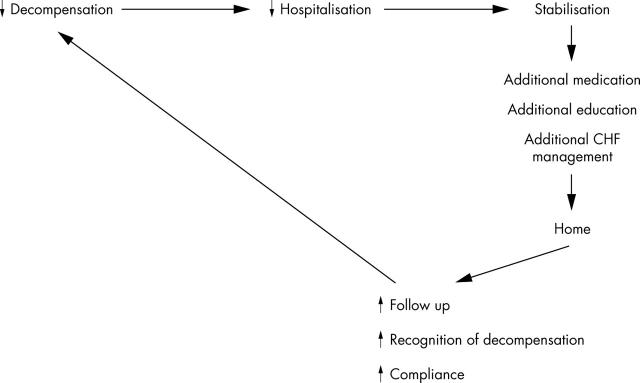

Figure 2.

How specialist intervention can break the vicious cycle of repeat hospitalisation.

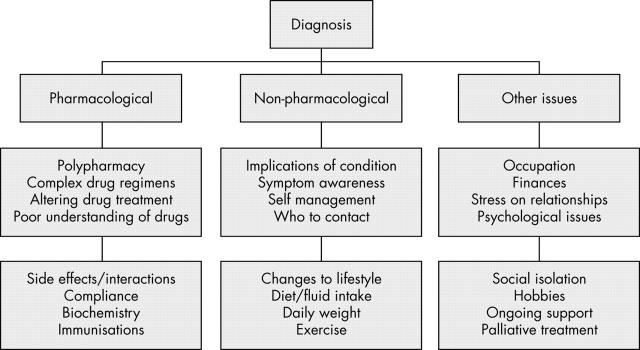

Figure 3.

The multiple needs of a heart failure patient following diagnosis.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blue L., Lang E., McMurray J. J., Davie A. P., McDonagh T. A., Murdoch D. R., Petrie M. C., Connolly E., Norrie J., Round C. E. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001 Sep 29;323(7315):715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron G., Bigas C., Linares E., Aranda J. M., Hernandez E. Nurse practitioner role in a chronic congestive heart failure clinic: in-hospital time, costs, and patient satisfaction. Heart Lung. 1983 May;12(3):237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali J. K., Kadakia S., Cooper R., Ferlinz J. Precipitating factors leading to decompensation of heart failure. Traits among urban blacks. Arch Intern Med. 1988 Sep;148(9):2013–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanumanthu S., Butler J., Chomsky D., Davis S., Wilson J. R. Effect of a heart failure program on hospitalization frequency and exercise tolerance. Circulation. 1997 Nov 4;96(9):2842–2848. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornowski R., Zeeli D., Averbuch M., Finkelstein A., Schwartz D., Moshkovitz M., Weinreb B., Hershkovitz R., Eyal D., Miller M. Intensive home-care surveillance prevents hospitalization and improves morbidity rates among elderly patients with severe congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1995 Apr;129(4):762–766. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Køber L., Torp-Pedersen C., Jørgensen S., Eliasen P., Camm A. J. Changes in absolute and relative importance in the prognostic value of left ventricular systolic function and congestive heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. TRACE Study Group. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation. Am J Cardiol. 1998 Jun 1;81(11):1292–1297. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalsen A., König G., Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading to hospital admission with decompensated heart failure. Heart. 1998 Nov;80(5):437–441. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S., Pearson S., Horowitz J. D. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern Med. 1998 May 25;158(10):1067–1072. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S., Vandenbroek A. J., Pearson S., Horowitz J. D. Prolonged beneficial effects of a home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and mortality among patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Feb 8;159(3):257–261. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]