Abstract

Intercellular communication by means of small signal molecules coordinates gene expression among bacteria. This population density-dependent regulation is known as quorum sensing. The symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021 possesses the Sin quorum sensing system based on N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHL) as signal molecules. Here, we demonstrate that the LuxR-type regulator ExpR binds specifically to a target sequence in the sinRI locus in the presence of different AHLs with acyl side chains from 8 to 20 carbons. Dynamic force spectroscopy based on the atomic force microscope provided detailed information about the molecular mechanism of binding upon activation by six different AHLs. These single molecule experiments revealed that the mean lifetime of the bound protein-DNA complex varies depending on the specific effector molecule. The small differences between individual AHLs also had a pronounced influence on the structure of protein-DNA interaction: The reaction length of dissociation varied from 2.6 to 5.8 Å. In addition, dynamic force spectroscopy experiments indicate that N-heptanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone binds to ExpR but is not able to stimulate protein-DNA interaction.

INTRODUCTION

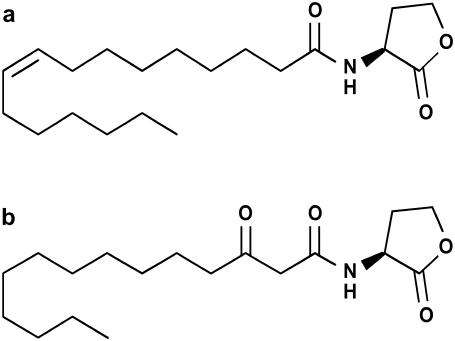

Quorum sensing (QS) is a form of population density-dependent gene regulation controlled by low molecular weight compounds called autoinducers, which are produced by bacteria. QS is known to regulate many different physiological processes, including the production of secondary metabolites, conjugal plasmid transfer, swimming, swarming, biofilm maturation, and virulence in human, plant, and animal pathogens (reviewed in Gonzalez and Marketon (1) and Swift et al. (2)). Many QS systems involve N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) as signal molecules (reviewed in Fuqua et al. (3)). These AHLs vary in length, degree of substitution, and saturation of the acyl chain (Fig. 1). Bacterial cell walls are permeable to AHLs, either by unassisted diffusion across the cell membrane (for shorter acyl chain length) or active transport (possibly for longer acyl chain length) (4). With the increase in the number of cells, AHLs accumulate both intracellularly and extracellularly. Once a threshold concentration is reached, they act as coinducers, usually by activating LuxR-type transcriptional regulators.

FIGURE 1.

AHLs. Of the synthesized AHLs, those with modifications in the acyl side chain are shown: (a) N-[(9Z)-hexadec-9-enoyl]-L-homoserine lactone (C16:1-HL) and (b) N-(3-Oxotetradecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (oxo-C14-HL).

Sinorhizobium meliloti is an α-proteobacterium that fixes atmospheric dinitrogen to ammonia in a symbiotic association with certain genera of leguminous plants, including Medicago, Melilotus, and Trigonella. In S. meliloti Rm1021, a QS system consisting of the AHL synthase SinI and the LuxR-type AHL receptors SinR and ExpR was identified (5). SinI is responsible for production of several long-chain AHLs (C12-HL – C18-HL) (6). The presence of a second QS system, the Mel system, controlling the synthesis of short-chain AHLs (C6-HL – C8-HL) was suggested (6). In addition to SinR, five other putative AHL receptors, including ExpR, were identified (7). As originally described for the model QS LuxI/LuxR system of Vibrio fischeri (8) and demonstrated for the TraR-AHL complex of Agrobacterium tumefaciens whose crystal structure was resolved (9), it is assumed that the LuxR-type regulators of S. meliloti are activated by binding of specific AHLs. Once activated, the expression of target genes is regulated by binding upstream of the promoter regions of these genes (10). The first target genes identified for the S. meliloti Sin system were the exp genes mediating biosynthesis of the exopolysaccharide galactoglucan. The expression of the exp genes not only relies on a sufficient concentration of Sin system-specific AHLs but also requires the presence of the LuxR-type AHL receptor ExpR (7,11). Data of transcriptomics and proteomics approaches suggested that the majority of target genes of the Sin system is controlled by ExpR (12,13). The S. meliloti Rm1021 wild-type strain carries an inactive expR gene due to disruption of its coding region by insertion element ISRm2011-1 (7). However, the spontaneous dominant mutation expR101 resulting from precise reading frame-restoring excision of the insertion element from the coding region unraveled the role of expR in regulation of galactoglucan biosynthesis (7). ExpR is highly homologous to the V. fischeri LuxR. Activated LuxR-type regulators usually bind to a consensus sequence known as the lux box, typically located upstream of the promoters of its target genes (10). However, the DNA binding site of ExpR has not yet been identified.

During the last decade, dynamic force spectroscopy (DFS) has developed into a highly sensitive tool for investigation of the interaction of single biomolecules (14), from complementary DNA strands (15) to ligand-receptor pairs (16–20) and cell adhesion molecules (21). Only most recently has protein-DNA interaction come under survey by DFS (22–26). In particular, DFS data have proven to complement the information gained from conventional molecular biology experiments in a detailed study of DNA binding of the regulator ExpG-activating transcription of the exp genes (25).

Most DFS experiments use either optical tweezers or an atomic force microscope (AFM) to measure dissociation forces of single bound complexes in the piconewton range. The molecular binding partners are attached to the micro- or nanoscale force sensor and a sample holder, respectively, by covalent chemistry. When both parts are brought into close contact, a specific bond between the individual molecules can form. By increasing the distance again, the bond is loaded until it finally severs. This event yields a discrete dissociation force. By systematic variation of the externally applied load, information on the energy landscape of the interaction can be derived (27,28): the equilibrium rate of dissociation, the mean lifetime of the bond, and the length of the dissociation path.

In this study, we identified the DNA binding site of ExpR in the region upstream of sinI and a spectrum of AHLs stimulating the DNA-binding activity of ExpR. Individual bound complexes were analyzed by DFS and kinetic parameters, which delicately depend on minute differences between effector molecules, were derived.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study have the following phenotypes: Escherichia coli M15[pREP4] (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) Nals, Strs, Rifs, Thi−, Lac−, Ara+, Gal+, Mtl−, F−, RecA+, Uvr+, Lon+; S. meliloti Rm1021 (29) Smr, Nalr, expR−; S. meliloti Rm1021 expR101 (Rm8530) (30) Smr, Nalr, expR+. S. meliloti strains were incubated at 30°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 2.5 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (LB/MC) or tryptone-yeast (TY) medium (31). E. coli strains were incubated at 37°C in LB medium. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations (μg/ml−1): for S. meliloti: gentamycin (Gm) 40, nalidixic acid (Nal) 10, streptomycin (Sm) 600; for E. coli: ampicillin (Ap) 100, gentamycin (Gm) 10.

Plasmid construction

Primers (AAAAGAATTCGAATATTACGTTGCTCGTACAGT and AATTAAGCTTGCTCTAACTTCTACAGGACT) (restriction sites are underlined) deduced from the S. meliloti Rm1021 sequence were used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the expR coding region. As template, genomic DNA was extracted from Rm8530, which carries the functional expR101 allele (7). A plasmid encoding an ExpR derivative with a six-histidine N-terminal tag was constructed as follows. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII and ligated into vector pWH844 (pQE-9 derivative, lacIq, 5.0 kb, Apr, T5, (His)6-tag) (32). Expression of this construct resulted in an ExpR protein with six N-terminally fused histidine residues [(His)6-ExpR]. Both expR and (his)6-expR preceded by the Shine-Dalgarno sequence derived from the multiple cloning site of vector pWH844 were also cloned into the broad host range vector (33), using primers TTAAGGATCCAATATTACGTTGCTCGTACA and AATTAAGCTTGCTCTAACTTCTACAGGACT and the restriction enzymes BamHI and HindIII. The resulting plasmids were transferred to S. meliloti Rm1021 by E. coli S17-1-mediated conjugation (34).

Expression and purification of protein

(His)6-ExpR was overexpressed in E. coli M15 and purified under nondenaturing conditions according to the QIAexpressionist handbook. Upon induction with 0.02 mM ITPG, the LB cell culture (800 mL) was grown at 25°C overnight. Cell pellet was harvested and resuspended in a 1/20 volume of lysis buffer containing 0.5% Triton-X 100, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mg DNase (SERVA, Heidelberg, Germany). Cell breakage was performed using a French Pressure Cell at 1380 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 44,000 × g, and the supernatant was loaded onto a 10 mL volume Ni-NTA affinity column (Qiagen). The column was washed with buffer (60 mL) containing 0.5% Triton-X 100, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole, followed by a second buffer (50 mL) containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole. Elution of the protein was by loading a buffer with an imidazole gradient (0.02–1.0 M, 50 mL) containing 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 0.5 M NaCl. Fractions (2 mL) were collected and analyzed with sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the protein concentration estimated using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany). Protein was stored in the elution buffer at 4°C and was stable for at least several months.

DNA labeling

The DNA probe used in the electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), the DNA footprinting assay, and the AFM experiments was derived from a 216-bp region (UpsinI) that included 31 bp of the 3′ end of sinR, the 156-bp intergenic region between sinR and sinI, and 29 bp of the 5′ end of sinI. UpsinI was PCR amplified using the flanking primers ATATAAGCTTTGTTCGACATGCTCTGATCC and ATATGAATTCCGACCGTTTCCGTTCACTAT and cloned into HindIII and EcoRI digested pUC18 (restriction sites in primer sequences are underlined). When the universal primers AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA and GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC were used in a PCR with the UpsinI cloned into pUC18 as the template, a 313-bp fragment was amplified. The DNA fragment was labeled using PCR amplification in which the 5′ primer contained either 5′Cy3 (for EMSAs), 5′fluorescein (for DNA footprinting assays), or 5′SH for AFM measurements.

UpsinICy3 fragment carrying point mutations at positions −106 (T replaced by G), −104 (T replaced by G), and −99 (G replaced by C) upstream of the sinI start codon was generated by PCR using two additional internal primers, pmut6upsinIfwd (GATTCCCCCACAAAGCGATTGCGAAAAAATGAGGAAATAA) and pmut6upsinIrev (CTCATTTTTTCGCAATCGCTTTGTGGGGGAATCTG). These primers bind to the ExpR protected region and contain the three bp alterations and complementary regions.

The internal primers were used in two separate PCR steps in combination with the flanking primers. The products of these PCRs were purified and combined and, upon annealing at the complementary regions, formed the template for the final PCR in which the flanking Cy3-labeled primers were used.

Synthesis of effector molecules

For the synthesis of AHLs with saturated side chains, fatty acids were converted into the corresponding acid chloride. They were slowly added to an ice cold solution of homoserine lactone hydrobromide and two equivalents of pyridine in methanol. After stirring for 3 h at room temperature, the solvent was removed in the vacuum and the residues dissolved in ethyl acetate. N-Octanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C8-HL), N-dodecanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C12-HL), N-pentadecanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C15-HL), N-octadecanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C18-HL), and N-eicosanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C20-HL) were synthesized in this manner. N-[(9Z)-hexadec-9-enoyl]-L-homoserine lactone (C16:1-HL, Fig. 1 a) was prepared from homoserine lactone hydrobromide and palmitoleic acid in a water-acetonitrile mixture by addition of base and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC). After 18 h the product was extracted from the reaction mixture using methylene chloride.

A previously reported synthesis protocol for β-keto esters was followed to prepare N-(3-oxotetradecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (oxo-C14-HL, Fig. 1 b) (35). One equivalent each of N,N′-dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DCC), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine, and 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-4,6-dione was added to a solution of lauric acid in methylene chloride. After stirring for 18 h at room temperature the solvent was evaporated. The residue was resuspended in ethyl acetate and washed with 1 M hydrochloric acid and saturated sodium chloride solution. The solvent was evaporated and the solid residue dissolved in acetonitrile and homoserine lactone was added. The dispersion was heated to reflux for 3 h. Evaporation of acetonitrile was followed by addition of ethyl acetate and aqueous workup. N-(3-oxohexadecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (oxo-C16-HL) was synthesized following an analogous protocol.

All synthesized AHL molecules were purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with acetonitrile/water/TFA gradients or by column chromatography with organic eluents and their structures were confirmed by mass spectrometry (MS) and proton NMR spectroscopy. The following substances were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (München, Germany): N-hexanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone (C6-HL), N-heptanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone (C7-HL), N-(3-oxooctanoyl)-DL-homoserine lactone (oxo-C8), N-decanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone (C10-HL), N-tetradecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone (C14-HL), and palmitoleic acid. Crude AHL extract from S. meliloti Rm1021 was obtained as described by Marketon et al. (6).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

The EMSA protocol has been described (22,25). The Cy3-labeled DNA wild-type fragment (UpsinICy3) or the mutated UpsinICy3 fragment were mixed with purified (His)6ExpR in a reaction buffer containing ∼0.25 nmol of sonicated herring testes DNA in a final volume of 20 μL of DNA-binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl). (His)6ExpR was included at 0.4 mM, and AHLs were added to a final concentration of 10 μM. The reactions were incubated at 24°C for 20 min. Loading buffer (5 μL, 78% glycerol) was added, and the reaction mixtures were loaded onto a 2% agarose gel at 4°C. After electrophoresis at 5 V/cm for 2 h, gel images were acquired using a Typhoon 8600 Variable Mode Imager (Amersham Bioscience, Freiburg, Germany).

DNA footprinting assays

The 5′fluorescein-labeled DNA fragment (UpsinI) was incubated with and without (His)6ExpR under conditions similar to the EMSA assay, except that benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich) was included, ranging 3–0.004 U, and the digestion mixture included 0.25 mM MgCl2 and 0.125 mM CaCl2. Sequencing products and fragments resulting from benzonase digest were separated on an ABI PRISM 377 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR

Two independent cultures of each strain were grown in TY medium and harvested at optical density (600 nm) 1.0. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription and real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were carried out using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) and a continuous fluorescence detector (DNA Engine OPTICON, Bio-Rad Laboratories) as described previously (36). Quantification was performed with the Opticon Monitor analysis software version 1.8. Cycle threshold values of the gene SMc02461, found to be substantially expressed at similar levels under a number of different conditions (36), were used as a reference for normalization. The following primers were used: for expE1 ATGGTGACGACTTGCTGTTC and GAGGTCGATGACGACATTGC; for expR CCGCATGAGAATCCGCTGAG and CCGTCGAAGAGGCCATGATT; for sinI CAAGATTCGTGGCTCCCTCA and ATGGTGACCTGGTTCGATGC; and for smc02461 CTTGCGGTTGTCGTTGACG and TTCATCAACGAGATTGCCGA.

Sample surface and AFM tip modification

For force spectroscopy measurements, sample surfaces and AFM tips were functionalized as described previously (22). Briefly, Si3N4 cantilevers (MSCT-AUHW, Veeco Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA, or OMCL-TR400PSA-HW, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were first activated by dipping for 10 s in concentrated nitric acid and silanized in a solution of 2% aminopropyltriethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich) in dry toluene for 2 h. After washing with toluene, the cantilevers were incubated with 1 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide-poly(ethylene glycol)-maleimide (Shearwater Polymers, Huntsville, AL) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with phosphate buffer, the cantilevers were incubated with 10 ng/μl of the DNA target sequence (see above) bearing a sulfhydryl label in binding buffer solution (100 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, pH 7.5) overnight at 4°C. The cantilevers were washed with binding buffer and used for force spectroscopy experiments. Modified tips were usable for at least 1 week if stored at 4°C.

Mica surfaces (Provac AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein) were silanized with aminopropyltriethoxysilane in an exsiccator and incubated with 4 μM (His)6ExpR protein and 20 μM bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate-sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, for 1 h at 4°C. The sample was washed with binding buffer afterward. Modified surfaces were stable for at least 2 days if stored at 4°C. A scheme of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3 a.

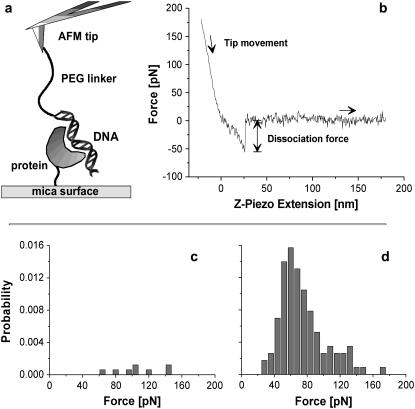

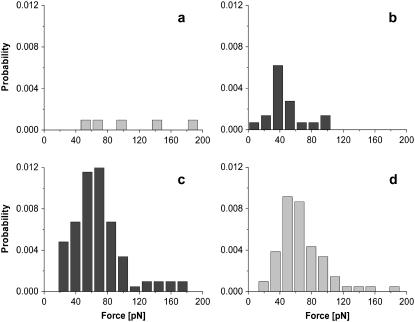

FIGURE 3.

Force spectroscopy measurements. (a) The experimental setup consists of a Si3N4 AFM tip with DNA fragments attached via poly(ethylene glycol) spacer molecules and a flat mica surface on which the (His)6ExpR proteins are immobilized. (b) Typical force-distance curve for the retraction of the tip from the sample surface at constant velocity. (c) Distribution of dissociation forces for the DNA-(His)6ExpR complex without effector (at v = 2000 nm/s) and (d) after adding 10 μM of oxo-C14-HL.

Dynamic force spectroscopy

Force spectroscopy measurements were performed with a home-built force spectroscopy setup based on a commercial AFM (Multimode, Veeco Instruments) at 25°C. Acquisition of the cantilever deflection force signal and the vertical movement of the piezo electric elements was controlled by a 16-bit AD/DA card (PCI-6052E, National Instruments, Austin, TX) and a high-voltage amplifier (600H, NanoTechTools, Echandens, Switzerland) via home-built software based on Labview (National Instruments). The deflection signal was low-pass filtered (<6 kHz) and box averaged by a factor of 10, giving a typical experimental data set of 2500 points per force-distance curve.

The spring constants of all AFM cantilevers were calibrated by the thermal fluctuation method (37) with an absolute uncertainty of ∼15%. Spring constants of the cantilevers used ranged from 8 pN/nm to 16 pN/nm (Veeco) and from 18 to 26 pN/nm (Olympus).

For loading rate-dependent measurements, the retract velocity of the piezo was varied while keeping the approach velocity constant. The measured force-distance curves were analyzed with a MATLAB program (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) and corrected to display the actual molecular distances calculated from the z piezo extension. To obtain the loading rate, the retract velocity was then multiplied by the elasticity of the molecular system, which was determined from the slope of the corrected force-distance curves on the last 20 data points before the dissociation events.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

(His)6ExpR activated by AHLs specifically binds to the sinR-sinI intergenic region

The S. meliloti ExpR protein shows homologies to LuxR-type AHL receptors, which have a C-terminal DNA binding and an N-terminal AHL binding domain that inhibits the activity of the C-terminal domain in the absence of the autoinducer (38). Marketon et al. (5) reported evidence for a positive sinR-dependent feedback regulation of sinI expression. A comparison of sinI mRNA levels in the expR− strain Rm1021 and the expR+ strain Rm1021 expR101 at a culture O.D.600 of 1.0 showed a 4.3-fold increase, indicating a positive regulation of sinI expression by ExpR. Moreover, we identified a lux box-like sequence (TATAGTACATGT) 70 bp upstream of sinI which constitutes a putative binding site for the LuxR-type regulators ExpR and SinR. Therefore, the sinR-sinI intergenic region was selected as a candidate for an ExpR target sequence.

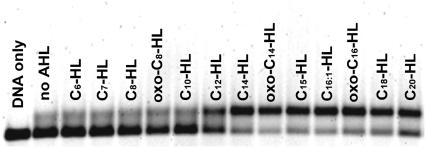

For binding assays ExpR protein was expressed in E. coli with an N-terminal His-tag ((His)6ExpR). Addition of AHLs during expression in E. coli strain M15 was not required for either stability or solubility. Binding of purified (His)6ExpR protein to a 313-bp fragment was analyzed in ensemble experiments by EMSA and at the single molecule level by force spectroscopy. This DNA fragment included 97-bp flanking sequences derived from the pUC18 vector, 31 bp of the 3′ end of sinR, the 156-bp sinR-sinI intergenic region, and 29 bp of the 5′ end of sinI. Various AHLs were tested for stimulation of the ExpR DNA-binding activity. These included AHLs found to be produced by bacteria but also AHLs which so far have not been found to be synthesized by bacteria, namely C15- and C20-HLs. (His)6ExpR showed minimal levels of binding to the DNA in the absence of AHL or in the presence of 10 μM of the short chain C6-, C7-, C8-, oxo-C8-, or C10-HLs (Fig. 2). In the presence of 10 μM C14-, oxo-C14-, C15-, C16:1-, oxo-C16-, C18-, or C20-HLs maximum stimulation of binding was observed, whereas C12-HL stimulated binding to a lesser extent (Fig. 2). No binding was observed in control experiments with DNA fragments derived from the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA-1) gene (22) (data not shown). Furthermore, activation of the DNA-binding activity of ExpR was not achieved by addition of palmitoleic acid, showing that the homoserine part of the AHLs is essential. These results indicate that AHL-activated (His)6ExpR binds specifically to the sinR-sinI intergenic region.

FIGURE 2.

AHL-dependent DNA binding of purified (His)6ExpR. A Cy3-labeled probe derived from the sinR-sinI intergenic region was used in the gel shift assay. AHLs were included in the binding reaction at 10 μM.

To investigate the ExpR-DNA interaction on a single molecule basis, the binding partners were covalently bound to the sample surface and to the AFM tip, respectively. The DNA fragment was attached to the tip via a polymer spacer, whereas the (His)6ExpR protein was immobilized on the surface by a short linker molecule coupled to one of the 11 ExpR lysines (Fig. 3 a). When the tip was approached to and retracted from the surface, the flexibility of the polymer chain allowed the DNA molecules to access the binding domains of immobilized proteins. By plotting the force acting on the AFM tip against the vertical position (given by the extension of the piezo actuator), dissociation events can be identified by a characteristic stretching of the polymer spacer before the point of bond rupture (where the tip snaps back to zero force). A typical force-distance curve is shown in Fig. 3 b. The dissociation forces from multiple approach-retract cycles under a single retract velocity were combined in a histogram. The total dissociation probability (events/cycles) remained below 0.5% for the bare protein-DNA system in buffer solution, the histogram consisting of scattered events (Fig. 3 c). The background signal, i.e., a series of measurements with a functionalized surface and an AFM tip without any DNA but prepared as normal in all other respects, was checked and revealed no dissociation events. The profile changed drastically when AHL was added to give a final concentration of 10 μM (oxo-C14-HL in the case of Fig. 3 d). The total dissociation probability increased to 8%–10%, and the dissociation forces form a distribution of almost Gaussian shape. The mean value of the Gaussian then equals the most probable dissociation force, with statistical errors given by standard deviation  for 95.4% confidence level). Data from this experiment indicate that ExpR binds to DNA even in the absence of any effector due to unspecific attraction (e.g., electrostatic forces) but the probability of binding is highly increased in the presence of a proper effector.

for 95.4% confidence level). Data from this experiment indicate that ExpR binds to DNA even in the absence of any effector due to unspecific attraction (e.g., electrostatic forces) but the probability of binding is highly increased in the presence of a proper effector.

Competition experiments were performed to address whether the observed binding forces are specific. Fig. 4 a shows a histogram of the dissociation forces similar to Fig. 3 d but activated by 10 μM C16:1-HL. After adding free DNA fragments (10 ng/μL) to the buffer solution, a distinct reduction of the binding probability was observed (Fig. 4 b). Washing with DNA-free buffer solution restores the initial unbinding probability (data not shown). In additional control experiments, the DNA-binding fragment on the AFM tip is replaced by EBNA-DNA fragments (EBNA) which lack the binding sequence. With this setup and in the presence of 10 μM C16:1-HL, nearly no binding could be observed at all (Fig. 4 c). These results clearly prove that the binding of the peptide with the native sequence actually takes place specifically at the binding sequence on the DNA.

FIGURE 4.

Force spectroscopy control experiments. (a) Distribution of the dissociation forces of DNA-(His)6ExpR complexes in the presence of 10 μM C16:1-HL. (b) After adding free DNA fragment (10 ng/μL) as competitor. (c) Additional control experiment with EBNA-DNA immobilized on the AFM tip and C16:1-HL-activated (His)6ExpR.

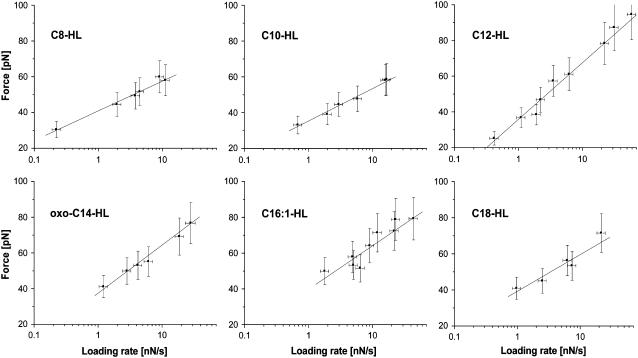

AFM force spectroscopy proved to be a sensitive tool to determine the influence of different effector molecules. Of the seven effectors tested, C8-HL, C10-HL, C12-HL, oxo-C14-HL, C16:1-HL, and C18-HL stimulated protein-DNA binding (see Fig. 7 for the most probable dissociation forces under different velocities). Only C7-HL caused no noticeable increase in activity when added to the buffer solution (see Fig. 8 a).

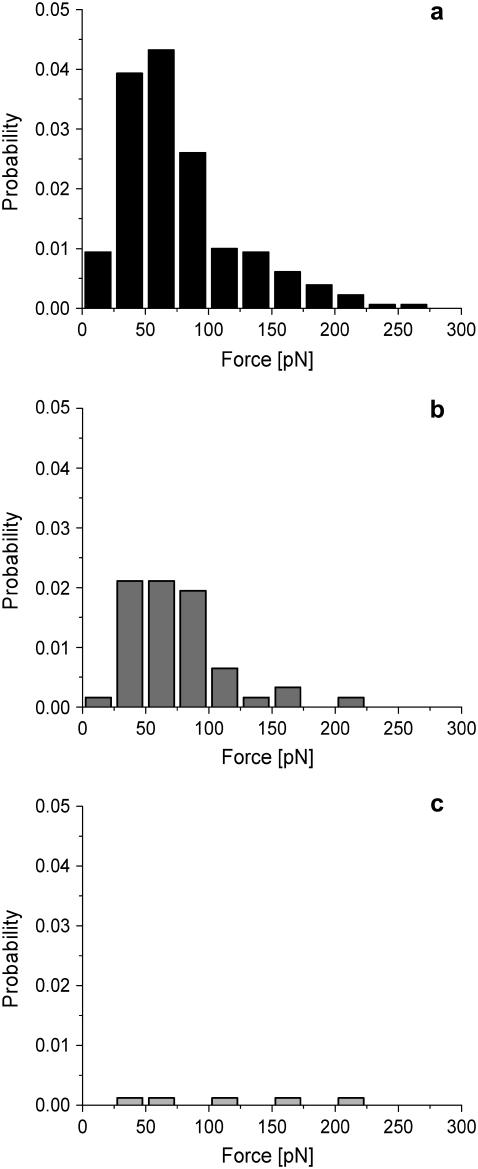

FIGURE 7.

DFS. Dissociation forces depend on the natural logarithm of the loading rate, r, with r = molecule elasticity × retract velocity. By systematical variation of the retract velocity, complexes formed by the (His)6ExpR protein and its DNA target sequence under the influence of different effectors where probed. Extrapolating the line fit to the state of zero external force yields the natural thermal off-rate koff for each data set. The derived values are summarized in Table 2.

FIGURE 8.

Stability of the protein-effector bond. (a) In the presence of C7-HL, no binding is observed. (b) After the sample was washed multiple times with buffer solution over the course of 1 h and C12-HL was added, the protein-DNA complex is still inactive. The reverse process was investigated with a new tip and sample surface: (c) In the presence of C12-HL, the protein-DNA complex shows its usual degree of activity. (d) C7-HL was added after the sample was washed multiple times over the course of 1 h. Activity is only slightly reduced. Obviously, C7-HL is not able to displace C12. Both experiments indicate a high stability of the protein-effector bond.

Complementation of an expR mutant confirms the activity of (His)6ExpR in vivo

To test the functionality of (His)6ExpR in vivo, the native expR gene and the (his)6expR fusion gene were cloned into the broad host range vector pJN105. Both plasmids were introduced to Rm1021, a strain in which the endogenous expR is not functional. After reverse transcription, real time PCR was applied to measure the abundance of RNA transcripts derived from expR and the galactoglucan biosynthesis gene expE1. Stimulation of expE2 expression has been previously found to be an indicator for ExpR activity (7,11). This gene is located just downstream of expE1 which is the first gene of the expE operon (39).

As a control, expR and expE1 expression was compared in the expR+ revertant Rm1021 expR101 and the Rm1021 expR− wild-type strain carrying the empty pJN105 vector. Compared to expE1 expression in strain Rm1021/pJN105, both expR and (his)6expR complemented strains Rm1021/pJQRexpR, and Rm1021/pJQR(his)6expR showed stimulation of expE1 expression (Table 1). Complementation of the Rm1021 expR− wild-type strain by expression of the (his)6expR gene demonstrated that the (His)6ExpR protein functions in vivo.

TABLE 1.

Gene expression of expR and expE1 derived from qRT-PCR

| Gene | Rm1021 expR101 vs. Rm1021/pJN105 | Rm1021/pJQRexpR vs. Rm1021/pJN105 | Rm1021/pJQR(his)6expR vs. Rm1021/pJN105 |

|---|---|---|---|

| expR | 22200 | 55600 | 79333 |

| expE1 | 55 | 37 | 38 |

Values indicate fold changes of RNA levels of expR and expE1 in strains Rm1021 expR101, Rm1021/pJQRexpR, and Rm1021/pJQR(his)6expR. The Rm1021 expR− wild-type carrying the empty vector pJN105 (Rm1021/pJN105) was used as reference. Transcript levels of gene SMc02461 were used for normalization. The error of the calculated normalized gene expression was <20%. This experiment was repeated three times with independent cultures.

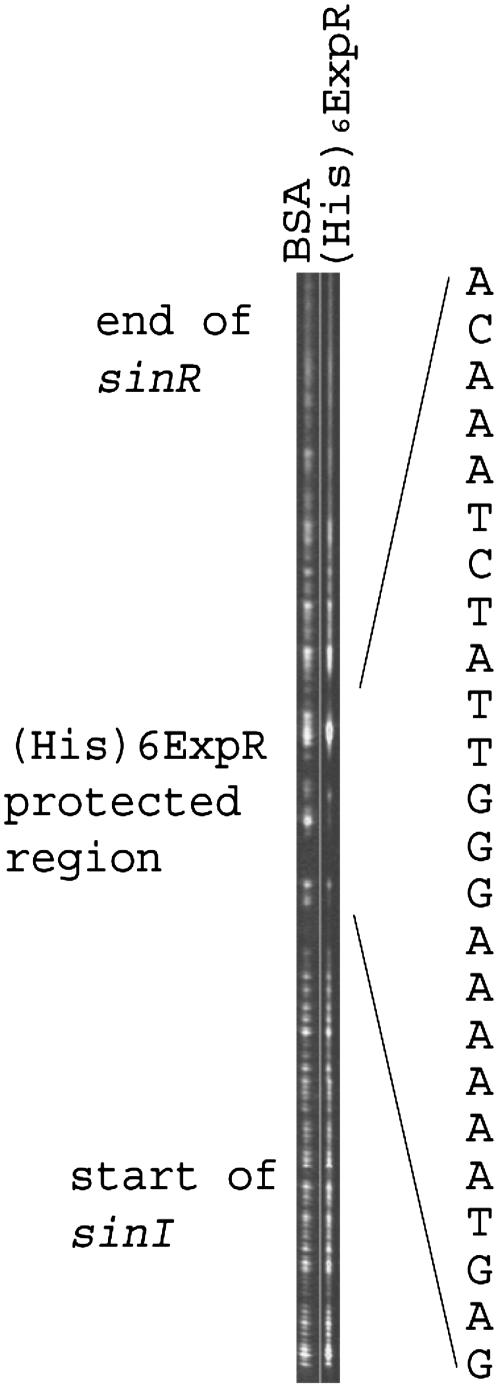

Binding of (His)6ExpR protects a 30-bp region including a lux box-like sequence against nucleolytic digestion

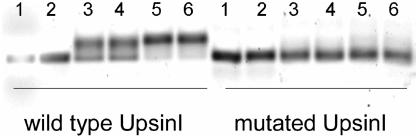

Benzonase footprinting was applied to identify the specific binding site of (His)6ExpR upstream of sinI. In the presence of 10 μM oxo-C14-HL, (His)6ExpR protected a 26-bp region adjacent to a downstream 13-bp lux box-like sequence (Fig. 5). EMSA experiments with subfragments of the sinI-sinR intergenic region indicated that a 46-bp sequence immediately upstream of the putative lux box is sufficient for binding of (His)6ExpR (data not shown). This indicates that the (His)6ExpR binding site is located just upstream of the putative lux box. The assay was repeated where (His)6ExpR was replaced with native ExpR in crude E. coli extract, resulting in protection of the same 26-bp DNA region (results not shown). Directed mutation of the ExpR binding site, involving three bps (positions T−106 replaced by G−106, T−104 replaced by G−104, and G−99 replaced by C−99 upstream of the sinI start codon) within the benzonase protected region (Fig. 5), resulted in the complete absence of binding by (His)6ExpR in the presence of oxo-C14-HL (Fig. 6). This finding further supports the involvement of the protected region in specific binding to ExpR.

FIGURE 5.

Benzonase protection of an upstream region of sinI by oxo-C14-HL-stimulated (His)6ExpR. A fluoroscein-labeled DNA fragment derived from the sinR-sinI intergenic region was preincubated in the presence of 10 μM oxo-C14-HL with either 2 μM bovine serum albumin (lane 1) or with 2 μM (His)6ExpR (lane 2) and was then partially digested with benzonase, as described in Materials and Methods. The DNA sequence protected by (His)6ExpR is indicated on the right side of the figure. An indication of the position of the footprint relative to the flanking genes and the lux box homolog is indicated on the left of the diagram.

FIGURE 6.

AHL-dependent DNA binding of purified (His)6ExpR to the Cy3-labeled UpsinI wild-type fragment and the UpsinI fragment carrying point mutations. The mutated UpsinI fragment contains three altered bps at positions −106 (T replaced by G), −104 (T replaced by G), and −99 (G replaced by C) upstream of the sinI start codon. Lanes 1 and 2, UpsinI only; lanes 3 and 4, UpsinI with (His)6ExpR; lanes 5 and 6, UpsinI with (His)6ExpR and oxo-C14-HL.

Dynamic force spectroscopy reveals that molecular interaction parameters of AHL-activated ExpR vary with different AHLs

The influence of the six effectors which stimulated ExpR-DNA binding was then studied in detail by DFS measurements. For each effector, typically 80–150 dissociation events of the protein-DNA complex (1000–2000 approach/retract cycles) were recorded at 5–9 different retract velocities ranging from 100 nm/s to 6000 nm/s while the approach velocity was kept constant at 2000 nm/s. These resulted in loading rates r = molecule elasticity × retract velocity in the range between 220 pN/s and 44000 pN/s.

When the dissociation forces are plotted against the corresponding loading rates on a logarithmic scale, a characteristic linear dependence becomes apparent (Fig. 7). This is in accordance with force spectroscopy theory (27,28), the fitting function being given as

|

wherein F is the most probable dissociation force, kBT = 4.114 pN nm (at 298 K) is a Boltzmann factor, r is the loading rate, and koff is the thermal off-rate under zero load. The molecular parameter xβ defines the distance between the minimum of the potential well of the bound state and the maximum of the energy barrier separating the bound state from the free state along the reaction coordinate. This is often interpreted as the depth of the binding pocket (see Merkel et al. (28) for a thorough analysis). By extrapolating the linear fit to the state of zero external force, the thermal off-rate koff of the ligand-receptor complex can be derived. The molecular interaction parameters gained from the experimental data in Fig. 7 are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Molecular interaction parameters for ExpR-DNA binding under various AHL effectors as derived from DFS

| HL | Reaction length xβ (Å) | Off-rate koff (s−1) | Mean lifetime (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C8 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 0.48 ± 0.16 | 2273 ± 758 |

| C10 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 1.43 ± 0.45 | 699 ± 220 |

| C12 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 5.40 ± 1.03 | 185 ± 35 |

| oxo-C14 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.48 ± 0.62 | 287 ± 51 |

| C16:1 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 2.19 ± 1.88 | 457 ± 392 |

| C18 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 1.32 ± 1.27 | 758 ± 729 |

The different effectors showed a distinct influence on the kinetics and structure of the ExpR-DNA binding. Most off-rates were close to koff = 2 s−1, which corresponds to a mean lifetime of ∼0.5 s for the bound protein-DNA complex. The notable exceptions are C8-HL, which caused an off-rate of koff = 0.5 s−1 (τ = 2.3 ± 0.8 s), and C12-HL with koff = 5.4 s−1 (τ = 0.19 ± 0.04 s). The measured reaction length xβ indicates three different states as well: the long-chain AHLs (oxo-C14-HL, C16:1-HL, and C18-HL) center around xβ ∼ 4.0 Å, whereas the short-chain AHLs (C8-HL and C10-HL) tend to higher values at xβ ∼ 5.5 Å, and C12-HL has a strikingly low reaction length of xβ ∼ 3 Å.

The lifetime of the ExpR-AHL complex exceeds the lifetime of the protein-DNA complex

Why is C7-HL not able to stimulate protein-DNA interaction (Fig. 8 a)? One likely explanation would be that it does not bind to the ExpR protein. But this is not the case. Even after C7-HL was removed from both the sample surface and the AFM tip by multiple washing steps with AHL-free buffer solution over the course of 1 h, addition of C12-HL yielded very few dissociation events (Fig. 8 b). It seems that most proteins retained a C7-HL effector which inhibited activation by C12-HL. This suggests that, although C7-HL binds to the ExpR protein, it is not able to change its conformation into an active state. This is a further indication that the chemical structure of a particular effector has a strong influence on the sterics of the ExpR protein and thereby on the kinetics of possible protein-DNA interactions.

The aforementioned experiment suggests a long lifetime of the C7-HL effector-protein complex, resulting in an effective inhibition of activation of ExpR by C12-HL. We performed an additional experiment in which C12-HL was the first AHL added, which showed its usual degree of activity with a fresh protein sample (Fig. 8 c). As in the previous experiment, sample surface and AFM tip were washed multiple times over the course of 1 h before the addition of the second AHL, C7-HL. Although the binding probability was marginally reduced after the washing step (Fig. 8 d), the system still showed a considerable degree of activity in the presence of C7-HL. In contrast to the lifetime of the protein-DNA complex (which is τ = 185 ± 35 ms in the case of C12-HL, see Table 2), the lifetime of the protein-effector bond seems to be much longer. ExpR-DNA kinetics can therefore be regarded as independent from AHL-ExpR kinetics, indicating that only the structural change of the protein induced by a particular AHL effector governed the properties of ExpR-DNA interaction in the DFS experiments.

CONCLUSION

Unlike the A. tumefaciens TraR LuxR-type QS regulator (40,41), (His)6ExpR did not require the addition of AHLs during expression in E. coli for either stability or solubility. AHLs were required for correct folding of TraR and completely embedded in a narrow cavity of the protein (9). Removal of AHLs bound to the V. fischeri LuxR through competition with halogenated furanones resulted in rapid degradation of LuxR, indicating that the signal molecules are essential for the stability of LuxR not only during folding but also for the duration of its lifetime (42). Due to its stability in the absence of AHLs the S. meliloti ExpR protein is an ideal model system for analysis of the AHL activation spectrum of a LuxR-type QS receptor.

A DNA binding site of ExpR was identified upstream of the AHL synthase gene sinI. The interaction is stimulated by a wide spectrum of AHLs that were previously found to be synthesized by bacteria and AHLs not yet found in bacteria, namely C15- and C20-HL. Whereas C7-HL containing an acyl chain with an odd number of C-atoms did not stimulate DNA binding, C15-HL also characterized by an odd-numbered acyl chain was active in the stimulation of DNA-binding activity. This suggests that the length of the acyl chain rather than an even or odd number of C-atoms is an important factor for the ability to stimulate the DNA-binding activity of ExpR. This effect was observed especially well at a single molecule level, where AFM force spectroscopy proved to be a sensitive tool for binding analysis of complex multiple-component systems. By this method, we also obtained evidence that C7-HL binds to the ExpR protein but is not able to stimulate protein-DNA interaction. Furthermore, since the interaction of C7-HL with ExpR appeared to prevent stimulation by C12-HL, this points to the possibility of an inhibitory effect of AHLs synthesized by an endogenous AHL synthase other than SinI or by other bacteria. C7-HL is a naturally occurring AHL produced by Rhizobium leguminosarum (43).

The wide range of acyl chain lengths results in significant variations of solubilities and, therefore, makes it difficult to determine and to compare kinetic parameters of AHL-activated ExpR in ensemble experiments. DFS has proven to be particularly useful in this respect since only values determined for ExpR proteins activated by a bound AHL molecule can be taken into account. In this manner, kinetic parameters of the molecular interaction between DNA and AHL-activated ExpR were determined.

Both the lifetimes of the bound complexes and the length scales of the dissociation processes varied with different AHLs bound to the protein. This supports the hypothesis that ExpR may regulate target genes differently in response to different SinI-dependent AHLs and is in agreement with previously reported specific ExpR-dependent effects of different AHLs on levels of proteins (13). It has been reported that diverse spectra of AHLs were synthesized in different culture media and growth phases (5,44). This may affect the availability of various AHLs for activation of the LuxR-type regulators under different growth conditions.

We obtained indirect evidence on the protein-effector interaction as well, implicating a very stable bond between ExpR and its associated AHLs. A tight interaction with their cognate AHLs was also reported for the A. tumefaciens TraR and the V. fischeri LuxR, although competition with halogenated furanones (42) and experiments showing that the LuxR-AHL complex can be reversibly inactivated by dilution (40,41) suggested a reversible binding of the signal molecules. Various LuxR-type regulators may exhibit differences in AHL accessibility and stability of the protein-AHL complex.

The DNA binding site of ExpR is located immediately upstream of a lux box-like sequence preceding the AHL synthase gene sinI. Since expression of sinI seems to be strongly dependent on sinR (5,45), it is possible that the lux box-like sequence constitutes the binding site of SinR. Hence SinR and ExpR may interact during binding to this DNA region.

Finally, we would like to stress the capacity of single molecule force experiments to analyze protein-DNA interactions with attention to molecular details of the binding mechanism: Evidently, a single C-atom more or less in the side chain of the AHL effector could make a big difference in functionality.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Borgmann for RT-PCR sinI results.

This work was supported by SFB 613 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- 1.Gonzalez, J. E., and M. M. Marketon. 2003. Quorum sensing in nitrogen-fixing rhizobia. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:574–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swift, S., J. A. Downie, N. A. Whitehead, A. M. Barnard, G. P. Salmond, and P. Williams. 2001. Quorum sensing as a population-density-dependent determinant of bacterial physiology. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 45:199–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuqua, C., M. R. Parsek, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:439–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson, J. P., C. V. Delden, and B. H. Iglewski. 1999. Active efflux and diffusion are involved in transport of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-to-cell signals. J. Bacteriol. 181:1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marketon, M. M., and J. E. Gonzalez. 2002. Identification of two quorum-sensing systems in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 184:3466–3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marketon, M. M., M. R. Groquist, A. Eberhard, and J. E. Gonzalez. 2002. Characterization of the Sinorhizobium meliloti sinR/sinI locus and the production of novel N-acyl homoserine lactones. J. Bacteriol. 184:5686–5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellock, B. J., M. Teplitski, R. P. Boinay, W. D. Bauer, and G. C. Walker. 2002. A LuxR homolog controls production of symbiotically active extracellular polysaccharide II by Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 184:5067–5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanzelka, B. L., and E. P. Greenberg. 1995. Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 177:815–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannini, A., C. Volpari, C. Gargioli, E. Muraglia, R. Cortese, R. De Francesco, P. Neddermann, and S. Di Marco. 2002. The crystal structure of the quorum sensing protein TraR bound to its autoinducer and target DNA. EMBO J. 21:4393–4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens, A. M., K. M. Dolan, and E. P. Greenberg. 1994. Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:12619–12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marketon, M. M., S. A. Glenn, A. Eberhard, and J. E. Gonzalez. 2003. Quorum sensing controls exopolysaccharide production in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 185:325–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoang, H., A. Becker, and J. E. Gonzalez. 2004. The LuxR homolog ExpR, in combination with the sin quorum sensing system, plays a central role in Sinorhizobium meliloti gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 186:5460–5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao, M., H. Chen, A. Eberhard, M. R. Gronquist, J. B. Robinson, B. G. Rolfe, and W. D. Bauer. 2005. sinI- and expR-dependent quorum sensing in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 187:7931–7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustamante, C., J. C. Macosko, and G. J. Wuite. 2000. Grabbing the cat by the tail: manipulating molecules one by one. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, G. U., L. A. Chrisey, and R. J. Colton. 1994. Direct measurement of the forces between complementary strands of DNA. Science. 266:771–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Florin, E.-L., V. T. Moy, and H. E. Gaub. 1994. Adhesion forces between individual ligand-receptor pairs. Science. 264:415–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinterdorfer, P., W. Baumgartner, H. Gruber, K. Schilcher, and H. Schindler. 1996. Detection and localization of individual antibody-antigen recognition events by atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:3477–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dammer, U., M. Hegner, D. Anselmetti, P. Wagner, M. Dreier, W. Huber, and H.-J. Güntherodt. 1996. Specific antigen/antibody interactions measured by force microscopy. Biophys. J. 70:2437–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ros, R., F. Schwesinger, D. Anselmetti, M. Kubon, R. Schäfer, A. Plückthun, and L. Tiefenauer. 1998. Antigen binding forces of individually addressed single-chain Fv antibody molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:7402–7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans, E., A. Leung, V. Heinrich, and C. Zhu. 2004. Mechanical switching and coupling between two dissociation pathways in a P-selectin adhesion bond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:11281–11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dammer, U., O. Popescu, P. Wagner, D. Anselmetti, H.-J. Güntherodt, and G. N. Misevic. 1995. Binding strength between cell adhesion proteoglycans measured by atomic force microscopy. Science. 267:1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartels, F. W., B. Baumgarth, D. Anselmetti, R. Ros, and A. Becker. 2003. Specific binding of the regulatory protein ExpG to promoter regions of the galactoglucan biosynthesis gene cluster of Sinorhizobium meliloti—a combined molecular biology and force spectroscopy investigation. J. Struct. Biol. 143:145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch, S. J. and M. D. Wang. 2003. Dynamic force spectroscopy of protein-DNA interactions by unzipping DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91:208103-1–208103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kühner, F., L. T. Costa, P. M. Bisch, S. Thalhammer, W. M. Heckl, and H. E. Gaub. 2004. LexA-DNA bond strength by single molecule force spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 87:2683–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgarth, B., F. W. Bartels, D. Anselmetti, A. Becker, and R. Ros. 2005. Detailed studies of the binding mechanism of the Sinorhizobium meliloti transcriptional activator ExpG to DNA. Microbiology. 151:259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckel, R., S. D. Wilking, A. Becker, N. Sewald, R. Ros, and D. Anselmetti. 2005. Single-molecule experiments in synthetic biology: an approach to the affinity ranking of DNA-binding peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44:3921–3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans, E., and K. Ritchie. 1997. Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys. J. 72:1541–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkel, R., P. Nassoy, A. Leung, K. Ritchie, and E. Evans. 1999. Energy landscapes of receptor-ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature. 397:50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meade, H. M., S. R. Long, G. B. Ruvkun, S. E. Brown, and F. M. Ausubel. 1982. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 149:114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glazebrook, J., and G. C. Walker. 1989. A novel exopolysaccharide can function in place of the calcofluor-binding exopolysaccharide in nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. Cell. 56:661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beringer, J. E. 1974. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 84:188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schirmer, F., S. Ehrt, and W. Hillen. 1997. Expression, inducer spectrum, domain structure and function of MopR, the regulator of phenol degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 179:1329–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman, J. R., and C. Fuqua. 1999. Development of an alternative controlled expression system for diverse bacteria: use of an araC-PBAD cassette to analyze quorum sensing in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Gene. 227:197–203.10023058 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology. 1:783–791. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oikawa, Y., K. Sugano, and O. Yonemitsu. 1978. Meldrums acid in organic-synthesis. 2. General and versatile synthesis of beta-keto-esters. J. Org. Chem. 43:2087–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker, A., H. Berges, L. Krol, C. Bruand, S. Rüberg, E. Capela, E. Lauber, E. Meilhoc, F. Ampe, F. J. de Bruijn, J. Fourment, A. Francez-Charlot, D. Kahn, H. Küster, C. Liebe, A. Pühler, S. Weidner, and J. Batut. 2004. Global changes in gene expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 under microoxic and symbiotic conditions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 17:292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutter, J. L., and J. Bechhoefer. 1993. Calibration of atomic-force microscope tips. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 7:1868–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slock, J., D. VanRiet, D. Kolibachuk, and E. P. Greenberg. 1990. Critical regions of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein defined by mutational analysis. J. Bacteriol. 172:3974–3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker, A., S. Rüberg, H. Küster, A. A. Roxlau, M. Keller, T. Ivashina, H. P. Cheng, G. C. Walker, and A. Pühler. 1997. The 32-kilobase exp gene cluster of Rhizobium meliloti directing the biosynthesis of galactoglucan: genetic organization and properties of the encoded gene products. J. Bacteriol. 179:1375–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urbanowski, M. L., C. P. Lostroh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2004. Reversible acyl-homoserine lactone binding to purified Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J. Bacteriol. 186:631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu, J., and S. C. Winans. 2001. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1507–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manefield, M., R. de Nys, N. Kumar, R. Read, M. Givskov, P. Steinberg, and S. Kjelleberg. 1999. Evidence that halogenated furanones from Delisea pulchra inhibit acylated homoserine lactone (AHL)-mediated gene expression by displacing the AHL signal from its receptor protein. Microbiology. 145:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lithgow, J. K., A. Wilkinson, A. Hardman, B. Rodelas, A. Wisniewski-Dye, P. Williams, and J. A. Downie. 2000. The regulatory locus cinRI in Rhizobium leguminosarum controls a network of quorum-sensing loci. Mol. Microbiol. 37:81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teplitski, M., A. Eberhard, M. R. Gronquist, M. Gao, J. B. Robinson, and W. D. Bauer. 2003. Chemical identification of N-acyl homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti strains in defined medium. Arch. Microbiol. 180:494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Llamas, I., N. Keshavan, and J. E. Gonzalez. 2004. Use of Sinorhizobium meliloti as an indicator for specific detection of long-chain N-acyl homoserine lactones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3715–3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]