Abstract

The potential cytostatic function of apolipoprotein (apo) E in vivo was explored by measuring neointimal hyperplasia in response to vascular injury in apoE-deficient and apoE-overexpressing transgenic mice. Results showed a significant increase in medial thickness, medial area, and neointimal formation after vascular injury in both apoE knockout and wild-type C57BL/6 mice. Immunochemical analysis with smooth muscle α-actin-specific antibodies revealed that the neointima contained proliferating smooth muscle cells. Neointimal area was 3.4-fold greater, and the intima/medial ratio as well as stenotic luminal area was more pronounced in apoE(−/−) mice than those observed in control mice (P < 0.05). The human apoE3 transgenic mice in FVB/N genetic background were then used to verify a direct effect of apoE in protection against neointimal hyperplasia in response to mechanically induced vascular injury. Results showed that neointimal area was reduced threefold to fourfold in mice overexpressing the human apoE3 transgene (P < 0.05). Importantly, suppression of neointimal formation in the apoE transgenic mice also abolished the luminal stenosis observed in their nontransgenic FVB/N counterparts. These results documented a direct role of apoE in modulating vascular response to injury, suggesting that increasing apoE level may be beneficial in protection against restenosis after vascular surgery.

Despite the recent reduction in mortality from myocardial infarction and other forms of ischemic heart disease, atherosclerosis remains the major cause of death in approximately half the population in industrialized countries. Currently available treatment for vascular occlusive disease includes percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, directional coronary atherectomy, and percutaneous delivery of balloon expandable stents. 1-5 However, despite a primary success rate of 90 to 95%, late restenosis of the artery occurs in 30 to 50% of patients within 3 to 6 months of the procedure. 6,7 Accelerated coronary arteriosclerosis is also a prominent complication associated with allograft cardiac transplant. 8 Accordingly, it would be worthwhile to gain additional understanding on the mechanism of restenosis and factors that determine individual differences in susceptibility to occlusive vasculopathy after these surgical operations.

Accelerated coronary arteriosclerosis because of restenosis after surgical operations is different from progressive atherosclerosis in that lipid deposition and macrophage foam-cell appearance are late events. Pathological studies revealed that narrowing of the coronary vessels in both restenosis and allograft arteriosclerosis are related to intimal hyperplasia, with abnormal proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells from the tunica media to the intima. 9-11 One hypothesis suggests that these accelerated forms of arteriosclerosis are because of immune-mediated endothelial injury, thus exposing the underlying vascular smooth muscle cells to mitogenic growth factors, which induces phenotypic conversion of the smooth muscle cells from the contractile-nonproliferating phenotype to the secretory proliferating phenotype. 12-15 However, more recent data revealed that differences in abnormal vascular remodeling, associated with inefficient compensatory enlargement of the arterial wall, is the contributory factor toward restenosis. 16,17 Although coronary stents have been used successfully to reduce vascular wall remodeling with a decrease in the rate of restenosis, 18,19 restenosis because of smooth muscle cell hyperplasia occurs after stenting in 20 to 30% of patients. 20,21 The key factors that are important for regulating smooth-muscle cell proliferation and in determining the severity of neointimal hyperplasia have not been completely elucidated.

Recent studies revealed that apolipoprotein (apo) E4 homozygosity is associated with increased risk of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in human patients. 22,23 The relationship between the ε4/4 genotype and restenosis seemed to be independent of serum cholesterol and apo(a) levels. 23 These results suggested a lipid transport-independent role of apoE in protection against vascular disease. Our previous studies showed that apoE inhibits oxidized low-density lipoprotein- and platelet-derived growth factor-induced smooth-muscle cell migration and proliferation in vitro. 24 Thus, apoE may have direct cell regulatory functions in the vessel wall. ApoE-deficient mice have been used previously to assess neointimal formation after various treatments. 25 However, the direct role of apoE in dictating the severity of the neointima in vivo remains unclear. The current study used apoE-deficient mice as well as mice with transgenic overexpression of human apoE3 to explore the importance of apoE level in dictating neointimal hyperplasia after mechanically induced injury of the vessel wall.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male apoE-null mice back-crossed to a C57BL/6 genetic background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The human apoE-transgenic mice were generously provided by Dr. John Taylor (Gladstone Institute, San Francisco, CA). Detailed characterization of these apoE transgenic mice was reported previously by de Silva et al. 26 These apoE transgenic mice were originally produced in the ICR strain background and were back-crossed with FVB/N mice in our institutional facility for seven generations to >99% genetic homogeneity in FVB/N background before experiments. The wild-type C57BL/6 and FVB/N mice were obtained initially from The Jackson Laboratory and were maintained as breeding colonies in our institution. These animals were used as controls for the apoE(−/−) and apoE transgenic mice in all experiments. The animals were maintained on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle and were fed a normal mouse chow diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI). Food and water were available ad libitum. The animals were used for experimentation when they reached 6 to 8 weeks of age, weighing ∼25 to 30 g. All animal experimentation protocols were performed under the guidelines of animal welfare by the University of Cincinnati, in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Human ApoE Assay

Human apoE level in the transgenic mice was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A 96-well microtiter plate was incubated overnight with 100 μl of a 2 μg/ml solution of mouse anti-human apoE monoclonal antibody 1D7 (Ottawa Heart Institute Research Corporation, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Nonspecific sites were then blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mg/ml Tween-20 and 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. One hundred μl of mouse serum was added to each well and the incubation was continued for 2 hours, followed by a 2-hour incubation with a 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-human apoE polyclonal antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). The plates were washed and then incubated for an additional 2 hours with a 1:5,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Immunoreactivity was determined by addition of ALP 10 substrate (Sigma Chemical Co.) and measuring absorbance at 405 nm. Purified human apoE isolated according to Rall et al 27 was used as the standard.

Carotid Artery Injury

Mechanically induced endothelial denudation was performed by modification of the method originally described by Lindner et al. 28 In this modification, 29 an epon resin probe made by forming an epon bead slightly larger than the diameter of the carotid artery (0.45 mm) on a 3-0 nylon suture instead of a guide wire was used for the arterial injury. The animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with a solution composed of ketamine (80 mg/kg body weight; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Inc., Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (16 mg/kg; The Butler Co., Columbus, OH) diluted in 0.9% NaCl. The mice were immobilized and the fur covering the neck from sternum to chin were removed with lotion hair remover (Nair; Carter-Wallace, Inc., New York, NY). Surgery was performed using a dissection microscope (Leica GZ6; Leica, Buffalo, NY). The entire length of left carotid artery was exposed and the artery was ligated immediately proximal from the point of bifurcation with a 7-0 silk suture (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Another 7-0 suture was placed around the common carotid artery immediately distal from the branch point of the external carotid. A transverse arteriotomy was made between the 7-0 sutures and the resin probe was inserted and advanced toward the aorta arch and withdrawn five times. The probe was removed and the proximal 7-0 suture was ligated. Once restoration of blood flow through the carotid branch points was confirmed, the incision was closed with a 5-0 sterile surgical gut (Ethicon, Inc.). All these procedures were performed within 20 minutes. Animals were allowed to recover in a 37°C heat box. The identical surgical procedure was applied to each animal to assure reproducibility of the results.

Tissue Preparation and Histological Staining

Fourteen days after inducing arterial injury, animals were anesthetized and perfused with 0.9% NaCl by placement of a 22-gauge butterfly angiocatheter in the left ventricle. The mice were subsequently perfusion-fixed in situ by infusion with 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.0) for 20 minutes at a constant pressure of 100 mmHg. The entire neck was dissected from each mouse and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for an additional 48 hours. The whole neck was decalcified for 48 hours before embedding in paraffin. Identical whole-neck cross-sections of 5 μm were made from the distal side of the neck beginning at the point of the distally ligated 7-0 suture. The whole-neck sections were used to evaluate both the injured and the uninjured control vessels on the same section. For each mouse, four levels of serial sections at 500-μm intervals were made, and the data collected were averaged which allowed for the measurement to represent lesion formation along the entire length of the artery. Parallel sections were subjected to routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well as to Verhoeff Van-Gieson staining of elastic lamina. Four unstained sections from each level were used for immunohistochemistry.

Morphometry

Morphometric analyses were performed on elastin-stained tissue. For each animal, four whole-neck cross-sections with both injured left and uninjured-control right carotid arteries were measured. Images were digitized and captured using a Sony video camera (Sony, New York, NY) connected to a personal computer. Measurements were performed at a magnification of ×200 using a Scion Image analysis computer program (Scion, Frederick, MD). For each artery, luminal area, area inside the internal elastic lamina, and the area encircled by external elastic lamina were measured. Medial area was calculated as area encircled by external elastic lamina-area inside the internal elastic lamina and intimal area was calculated as area inside the internal elastic lamina-luminal area. To calculate the medial thickness for each vessel cross-section, the linear distance between internal elastic lamina and external elastic lamina was measured independently in four places, each at 90° apart and averaged. From these measurements, the ratio of intimal area and medial area, and the percent of luminal stenosis (100 × intimal area/area inside the internal elastic lamina) were calculated.

Immunohistochemistry

For all staining, sections were deparaffinized with xylene by incubating for 10 minutes three times and then dehydrated with a series of graded ethanol from 70 to 100% for 10 minutes each. Slides were then washed in distilled water for 5 minutes, and endogenous peroxidase activities were blocked by incubating for 30 minutes with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in PBS containing Triton X-100 (Sigma Chemical Co.). Slides were then washed three times in the same solution without H2O2 for 15 minutes each. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation for 30 minutes with 1.5% serum in PBS containing Triton X-100.

For the identification of smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-smooth muscle α-actin (Clone 1A4; Sigma Chemical Co.) at 1:3,000 dilution or anti-Von Willebrand Factor (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) at 1:100 dilution, respectively. The slides were washed three times for 15 minutes each with PBS containing Triton X-100 and then incubated for 1 hour at 23°C with 0.5% biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) for anti-smooth muscle cell α-actin or 0.5% biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for Von Willebrand Factor in the same solution containing 1.5% normal serum. Slides were then washed as described above, and then incubated with the avidin-peroxidase complex reagent (Peroxidase Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 hour at 23°C. The reaction was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine.

Identification of proliferating cells in the S phase of the growth cycle was accomplished by injecting the mice with three doses of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU, 50 mg/kg; Sigma Chemical Co.) intraperitoneally at 24, 8, and 1 hour before their sacrifice, followed by immunohistochemical analysis with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU (Clone BU33, diluted 1:300; Sigma Chemical Co.). Cells in the G1 growth phase were identified by immunohistochemical staining with the mouse monoclonal anti-cyclin D1 antibody, DCS-6 (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA) at a dilution of 1:20. The sections were pretreated by incubation with 4 mol/L HCl for 30 minutes at 37°C and neutralized in 0.2 mol/L borate buffer, pH 9.0. After a 15-minute washing with PBS containing Triton X-100, the sections were further incubated with 0.1% trypsin for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by blocking endogenous peroxidase and nonspecific binding sites as described above. The reaction was visualized using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit as described above.

Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. When only two groups (injured arteries and contralateral control arteries) were compared, differences were assessed by a paired Student’s t-test. Multiple comparisons were first tested by analysis of variance. When the analysis of variance demonstrated significant differences, individual mean differences were analyzed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Statistical software SigmaStat (Version 2.0, Jandel Co., San Rafael, CA) was used in statistical analysis. For all statistical analyses, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

This study used an epon resin probe on a 3-0 nylon suture to induce arterial injury in mice. Immunohistochemical staining with Von Willebrand Factor antibodies demonstrated that the resin probe could introduce consistent denudation of the endothelium (Figure 1) ▶ . Importantly, endothelial denudation by resin probe did not result in damage of the elastic lamina (Figures 2 and 3) ▶ ▶ . Thus, this procedure is ideally suitable to evaluate neointimal hyperplasia as a consequence of endothelial denudation with minimal trauma to the underlying medial smooth muscle cells. Animals with damaged elastic lamina after mechanically induced injury were excluded from subsequent characterization.

Figure 1.

Von Willebrand Factor immunohistochemical staining of control (a) and injured (b) carotid arteries. Paraffin sections were obtained from a C57BL/6 mouse 1 hour after mechanically induced injury of the left carotid artery. The sections were incubated with a polyclonal antibody against Von Willebrand Factor at a dilution of 1:100. Immunoreactivity was detected by incubation with 0.5% biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, followed by incubation with avidin-peroxidase complex and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs of a whole-neck section with H&E staining. Mechanically induced endothelial denudation was performed on the left carotid artery of an apoE-null mouse using a 3-0 nylon suture with a 0.45-mm epon bead. The mouse was sacrificed after 14 days, perfusion-fixed with 10% buffered formalin, and the whole neck was decalcified and embedded in paraffin. Four levels of serial sections at 500-μm intervals were made. a: Whole neck section with both the injured left carotid artery and the uninjured right carotid artery. Scale bar, 100 μm. b and c: Magnified versions of the uninjured and injured arteries, respectively. Scale bars, 50 μm. The arrows indicate the external elastic laminae and the arrowheads indicate the internal elastic laminae in each section.

Figure 3.

Response of C57BL/6 wild-type and apoE(−/−) mice to vascular injury. Mechanically induced injury of left carotid arteries in mice were performed 14 days before their sacrifice. Representative photomicrographs of the uninjured (left) and injured (right) carotid arteries from a C57BL/6 mouse (a–d) and apoE(−/−) mouse (e–h). Paraffin sections of the carotid arteries were stained with Verhoeff Van-Gieson (a and b and e and f) and H&E (c and d and g and h). The arrows indicate the external elastic laminae and the arrowheads indicate the internal elastic laminae in each section. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Examination of uninjured carotid arteries in normal C57BL/6 mice revealed three clearly delineated elastic lamina separating two layers of medial smooth muscle cells (Figure 3) ▶ . Representative histology data comparing injured and uninjured carotid arteries from a control and two apoE-null mice are shown in Figure 3 ▶ . Although little or no cells could be observed in the intima, within the innermost internal elastic lamina, of either apoE(+/+) or apoE(−/−) mice before injury (Figures 2 and 3) ▶ ▶ , a significant number of cells was found to be accumulated in the intima 14 days after injury of the carotid arteries (Figures 2 and 3) ▶ ▶ . Immunohistochemical analysis with smooth muscle cell-specific α-actin antibodies identified the majority of cells in injured and uninjured media, as well as in the neointima after arterial injury, as smooth muscle cells (Figure 4) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of smooth muscle α-actin in control (a) and injured carotid arteries (b) of an apoE(−/−) mouse. Paraffin sections were obtained 14 days after mechanically induced injury of the mouse carotid artery. The sections were incubated with a monoclonal antibody against α-smooth muscle cell α-actin at a dilution of 1:3,000. Immunoreactivity was detected by incubation with 0.5% biotinylated anti-mouse IgG, followed by incubation with avidin-peroxidase complex and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Scale bar, 50 μm.

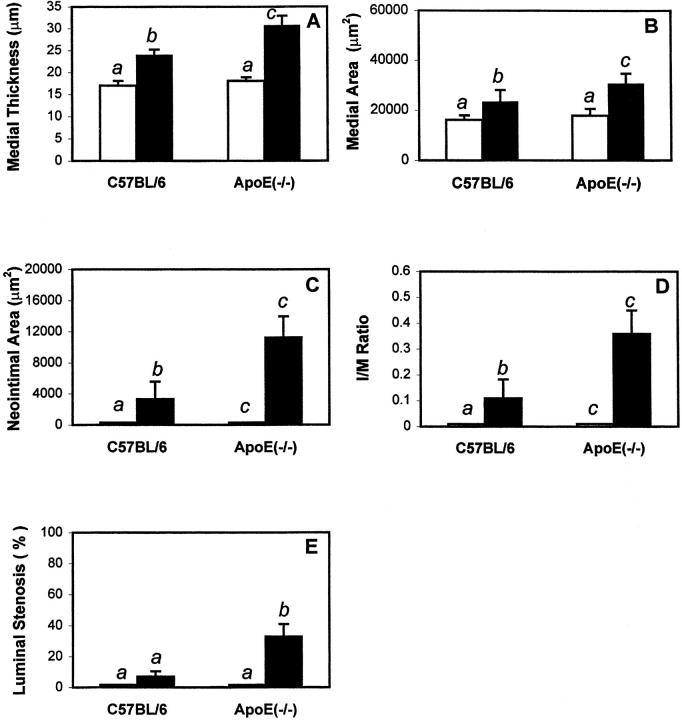

Morphometric analysis of the complete set of data clearly demonstrated significant increases in medial thickness, medial area, and neointimal formation (defined as an increase in intimal area) after vascular injury in both C57BL/6 control and apoE(−/−) mice (Figure 5, A–C) ▶ . Interestingly, the severity of neointimal formation in response to arterial injury was found to be 3.4-fold greater in apoE(−/−) mice in comparison with that in the C57BL/6 control mice (11,223.75 ± 2,715.4 μm 2 versus 3,323.98 ± 2,231.65 μm2, P < 0.05) (Figure 5C) ▶ . Analysis of BrdU-labeled cells revealed an eightfold and fivefold increase in the number of proliferating cells in the media and intima of apoE(−/−) mice compared to that in control animals (P < 0.05) (Figure 6a ▶ and Table 1 ▶ ). The greater neointimal formation in apoE(−/−) mice also resulted in the significant increase of intima/media ratio in apoE-null mice in comparison with that observed in the C57BL/6 control mice (0.11 ± 0.073 versus 0.359 ± 0.091, P < 0.05) (Figure 5D) ▶ . In addition, luminal stenosis was found to be more severe in the apoE(−/−) mice after arterial injury (32.8 ± 8.01% versus 7.0 ± 3.58% in control mice, P < 0.05) (Figure 5E) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Morphometric quantitation of control (open bars) and injured (filled bars) carotid arteries from C57BL/6 wild-type and apoE(−/−) mice. Carotid artery injury was performed using 3-0 sutures containing 0.45-mm epon beads. The animals were sacrificed after 14 days for tissue analysis. Medial thickness (A) was calculated as the average linear distance between the internal and external elastic lamina measured in four places at 90° apart. Medial area (B) was calculated as the area encircled by external elastic lamina minus the area encircled by the internal elastic lamina. Neointimal area (C) was determined by subtracting the luminal area from the area encircled by the internal elastic lamina. The intima-to-media ratio (D) was determined based on the data in B and C. Luminal stenosis (E) was calculated as the percentage of the area inside the internal elastic lamina occupied by the intimal area in the injured carotid arteries. The data represent the mean ± SEM from eight C57BL/6 and 12 apoE(−/−) mice. Scale bars with different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemical staining of BrdU in control (a, c, e, and g) and injured (b, d, f, and h) carotid arteries from C57BL/6, apoE (−/−), FVB/N, and apoE transgenic mice. Paraffin section were obtained 14 days after mechanically induced injury of the mouse carotid artery. The sections were pretreated with 4 mol/L HCl and 0.1% trypsin for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by incubation with a monoclonal antibody against BrdU at a dilution of 1:300. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Table 1.

Analysis of Proliferating Cells in Injured Carotid Arteries of Mice

| Mice | n | BrdU-labeled cells/cross-section | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media | Intima | ||

| C57Bl/6 | 7 | 1.44 ± 0.58 | 6.78 ± 1.66 |

| ApoE(−/−) | 10 | 12.56 ± 3.13* | 36.44 ± 10.84* |

| FVB/N | 5 | 16.00 ± 4.09 | 49.60 ± 9.94 |

| ApoE Transgenics | 9 | 3.00 ± 1.01* | 15.00 ± 5.29* |

Proliferating cells in the media and intima after mechanically induced arterial injury was determined by counting the number of BrdU-positive cells in each section. The data represent the mean ± SEM. * , Significant difference from their respective control group at P < 0.05.

Consideration was given to the fact that, in addition to difference in apoE level, the apoE(−/−) mice also had significantly high plasma lipid levels than the C57BL/6 control mice even under basal low-fat low-cholesterol diet. 30,31 Thus, the difference observed in arterial response to injury in these animals may be attributed to differences in either apoE level or plasma lipid level, or both. To discern these possibilities, arterial response to mechanically induced injury in human apoE3 transgenic mice was investigated. The apoE transgenic mice used in this study were originally produced in the ICR strain 26 and were back-crossed with FVB/N mice for seven generations to >99% genetic homogeneity in FVB/N background. Serum apoE levels in these transgenic mice ranged from 25 to 35 mg/dL, and their serum lipid levels were similar to those of the control FVB/N mice (Table 2) ▶ . Representative histology data after arterial injury of FVB/N control mice and apoE transgenic mice are shown in Figure 7 ▶ . Interestingly, the FVB/N mice were found to have a more pronounced arterial response to injury, with more severe neointimal formation, than those observed with the C57BL/6 control mice (compare Figures 3 and 7 ▶ ▶ ). However, neointimal formation in response to arterial injury was significantly reduced in the apoE-transgenic mice (Figures 7 and 8) ▶ ▶ . Note that the thickening is because of cellular accumulation in the neointima and not thrombus formation as shown by H&E staining (Figures 3 and 7) ▶ ▶ . Corresponding morphometric analysis of the complete set of data showed that medial thickness and medial area were significantly increased in both wild-type FVB/N and apoE transgenic mice after arterial injury. No significant difference was observed in these parameters between the wild-type and apoE transgenic mice (Figure 8, A and B) ▶ . However, neointimal area as well as the intima/media ratio in apoE transgenic mice were significantly lower than their wild-type counterparts after arterial injury (P < 0.05) (Figure 8, C and D) ▶ . Importantly, in the FVB/N mice, luminal stenosis of the injured carotid artery was found to be 16.5 ± 6.75%, whereas stenosis of the injured artery in the apoE transgenic mice was 4.3 ± 1.69% (P < 0.05) (Figure 8E) ▶ . The decrease in neointimal area and intima/media ratio observed in the apoE transgenic mice coincided with a threefold to fivefold decrease in the number of BrdU-labeled cells in these animals in comparison with that observed in the wild-type FVB/N mice (P < 0.05) (Figure 6 ▶ and Table 1 ▶ ).

Table 2.

Human ApoE and Lipid Levels in FVB/N and ApoE Transgenic Mice

| Mice | Human ApoE (mg/dL) | Triglyceride (mg/dL) | Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FVB/N | N.A. | 83.56 ± 23.6a | 93.7 ± 15.0b |

| ApoE-tg | 30 ± 5 | 71.89 ± 23.0a | 77.1 ± 9.6b |

| C57Bl/6 | N.A. | 81.54 ± 27.6c | 65.8 ± 17.6d |

| ApoE KO | N.A. | 125.60 ± 50.3c | 275.7 ± 77.7c |

N.A., not applicable.

Lipid levels with different superscript letters are different at P < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Response of FVB/N wild-type and human apoE3 transgenic mice to vascular injury. Mechanically induced injury of left carotid arteries in mice were performed 14 days before their sacrifice. Representative photomicrographs of the uninjured (left) and injured (right) carotid arteries from a FVB/N mouse (a–d) and apoE3 transgenic mouse (e–h). Paraffin sections of the carotid arteries were stained with Verhoeff Van-Gieson (a and b and e and f) and H&E (c and d and g and h). The arrows indicate the external elastic laminae and the arrowheads indicate the internal elastic laminae in each section. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Figure 8.

Morphometric quantitation of control (open bars) and injured (filled bars) carotid arteries from FVB/N wild-type and human apoE3 transgenic mice. Carotid artery injury was performed using 3-0 sutures containing 0.45-mm epon beads. The animals were sacrificed after 14 days for tissue analysis. Medial thickness (A), medial area (B), neointimal area (C), the intima-to-media ratio (D), and luminal stenosis (E) were calculated as described in the legend to Figure 5 ▶ . The data represent the mean ± SEM from seven FVB/N and six apoE transgenic mice. Scale bars with different letters indicate significant difference at P < 0.05.

Our previous in vitro studies showed that apoE inhibits platelet-derived growth factor- and oxidized low-density lipoprotein-stimulated smooth muscle cell proliferation via suppression of cyclin D1 activation. 24 To determine whether similar effects are occurring in vivo, cyclin D1 expression after arterial injury was determined in control, apoE(−/−), and apoE transgenic mice. Although only a minimal level of cyclin D1 expression was evident in the uninjured carotid arteries, cyclin D1 expression was clearly detected in the injured arteries of the mice regardless of their genotype (Figure 9) ▶ . The anti-cyclin D1-positive cells were clearly more abundant in the injured arteries of apoE(−/−) mice compared to that observed in their control C57BL/6 counterparts (Figure 9, b and d) ▶ . In contrast, anti-cyclin D1-positive cells were more abundant in the injured arteries of FVB/N mice than the apoE transgenic mice (Figure 9, f and h) ▶ .

Figure 9.

Immunohistochemical staining of cyclin D1 in control (a, c, e, and g) and injured (b, d, f, and h) carotid arteries from C57BL/6 (a and b), apoE (−/−) (c and d), FVB/N (e and f), and apoE transgenic mice (g and h). Paraffin sections were obtained 14 days after mechanically induced injury of the mouse carotid artery. The sections were pretreated with 4 mol/L HCl and 0.1% trypsin for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by incubation with a monoclonal antibody against cyclin D1 at a dilution of 1:20. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Discussion

The apoE knockout mouse has been used as an animal model for studying vascular occlusive diseases since its generation a number of years ago. 30,31 Most of these studies have focused on their robust atherosclerotic lesions developed as a consequence of overt hypercholesterolemia. Thus, numerous studies have been described on how modulation of lipid metabolism in these animals may alter their susceptibility and severity of atherosclerosis. The rationale for these studies is based on the well-established function of apoE as a mediator of plasma cholesterol homeostasis. 32 More recently, apoE knockout mice have also been used to study the effectiveness of various treatments on neointimal formation in accelerated arteriosclerosis because of endothelial denudation or cardiac transplant. 25,33 However, the precise role of apoE deficiency in contributing to the severity of the neointima has not been addressed directly. Results of the current study, showing an increased number of smooth muscle cells in the intima of apoE-deficient mice after arterial injury along with decreased neointimal formation in mice overexpressing the human apoE3 transgene, strongly suggested a direct role of apoE in modulating vascular response to injury.

The animals used in the current study were maintained on a low-fat diet without cholesterol supplementation. Although the plasma cholesterol levels in the apoE knockout mice were significantly higher than that observed in the C57BL/6 control mice, the plasma cholesterol levels of the human apoE3 transgenic mice were not significantly different from that in their control FVB/N counterparts (Table 2) ▶ . Thus, the effect of apoE on vascular homeostasis cannot be fully explained by its effect on plasma cholesterol level. Although the plasma cholesterol level may be one factor that modulates arterial response to injury, the protective effect of the apoE transgene against neointimal hyperplasia suggests that the level of apoE in the circulation may also be an important determinant in vascular response to injury. Although the apoE transgene does not alter plasma cholesterol level, it may have lipid-related effects in the vessel wall. These may include its effect of cellular cholesterol efflux and/or in routing of lipoproteins through receptor-mediated clearance mechanisms. However, the data are also consistent with the hypothesis that apoE may be protective in the vasculature via a process that is independent of its lipid transport properties.

A lipid-lowering independent role of apoE in protection against vascular occlusive diseases has been proposed previously based on several indirect observations. These include the ability of intravenously injected apoE to inhibit atheroma formation in Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits without affecting their plasma cholesterol concentrations, 34 and the ability of arterial wall-derived apoE to inhibit diet-induced atherosclerosis without affecting plasma cholesterol levels in transgenic mice. 35 The direct effect of apoE in limiting neointimal hyperplasia is also consistent with previous in vitro observations which showed that apoE has additional functions independent of cholesterol transport. For example, apoE has been shown to be an anti-oxidant capable of protecting cells against oxidative insults. 36 Because reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide seemed to be required for the activation of quiescent smooth muscle cells, 37 apoE may limit neointimal hyperplasia by reducing the level of reactive oxygen species in the arterial wall. More recently, we showed that apoE also has direct cell regulatory functions, including the ability to inhibit smooth-muscle cell migration and proliferation in response to oxidized low-density lipoprotein and platelet-derived growth factor. 24 Medial and intimal staining for BrdU-labeled cells suggests that apoE can reduce cellular proliferation in vivo, whereas the absence of apoE allows for increased proliferation and subsequent intimal thickening. Similar to the in vitro effects of apoE on smooth muscle cell functions, the cytostatic functions of apoE in vivo also seemed to be mediated via its inhibition of cyclin D1 gene expression in response to mechanically induced injury of the vasculature.

The results of the current study emphasized a direct cytostatic effect of apoE on the vessel wall and underscored the potential for using apoE gene therapy as treatment for vascular diseases. Kashyap et al 38 have already shown that intravenous infusion of recombinant adenovirus containing the human apoE gene can effectively reduce plasma cholesterol level and suppress atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Hasty et al 39 showed that transduction of bone marrow with apoE-expressing retrovirus was also effective in reducing early foam-cell lesion formation in apoE-deficient mice. Although the latter study showed that arterial macrophage expression of apoE had no beneficial effects during the later stages of atherosclerosis, the results of the current study suggest the potential benefit of apoE gene therapy in combination with vascular surgery for the treatment of vascular occlusive diseases. The ability of apoE to inhibit neointimal formation and to decrease luminal stenosis highlighted the potential of apoE therapy as a viable option in lowering the risk of restenosis after vascular surgery.

Although the current study is focused on comparing the effect of apoE deficiency or its enrichment on vascular response to injury, it is noteworthy that the two groups of control mice, namely the C57BL/6 and the FVB/N mice, displayed significant difference in the severity of neointimal formation in response to arterial injury. This observation is consistent with the recent report of strain differences in neointimal hyperplasia in rats. 40 These two studies indicated a possible genetic influence on the development of neointima after vascular injury. Interestingly, our data showed that neointimal hyperplasia was more severe in FVB/N mice than in C57BL/6 mice. Thus, the difference in severity of neointimal hyperplasia in response to arterial injury between the two inbred strains of mice diverse from their documented susceptibility to diet-induced atherosclerosis, in which C57BL/6 mice were consistently found to be the most susceptible strain. 41 This observation, along with observation of apoE protection against both atherosclerosis and vascular response to injury, suggests that pathogenesis of these vascular diseases may be controlled by distinct and overlapping genetic factors. With the identification of inbred mouse strains differing in their vascular response to injury, we can now take advantage of advances made in the development of high-resolution genetic linkage maps in the mouse model 42 to identify gene(s) that are important in determining the risk and severity of neointimal formation in response to arterial injury. Such information will be useful to identify patients at risk for restenosis after vascular surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John M. Taylor of the Gladstone Institute for Cardiovascular Disease for providing us with the apoE transgenic mice; Dr. Jay Hoying for the advice on performing arterial injury in mice; Lisa Artmayer for technical assistance with the histology data; Scot Lindeman and Zachary Moore for their assistance with the animal colony in our institution and immunohistochemistry; and Jay Card for his technical assistance with the graphic imaging.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to David Y. Hui, Ph.D., Department of Pathology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 231 Albert Sabin Way, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0529. E-mail: huidy@email.uc.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL-61332 (to D. Y. H.) and an American Heart Association grant-in-aid SW-96-43-S (to D. P. W.).

References

- 1.Glagov S: Intimal hyperplasia, vascular modeling, and the restenosis problem. Circulation 1994, 89:2888-2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dussaillant GR, Mintz GS, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Popma JJ, Wong SC, Leon MB: Small stent size and intimal hyperplasia contribute to restenosis: a volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995, 26:720-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney M, Pieczek A, Haley L, Losordo DW, Andres V, Schainfeld R, Rosenfield K, Isner JM: Histopathology of in-stent restenosis in patients with peripheral artery disease. Circulation 1997, 95:1998-2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann R, Mintz GS, Dussaillant GR, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Kent KM, Griffin J, Leon MB: Patterns and mechanisms of in-stent restenosis. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 1996, 94:1247-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono K, Imazu M, Ueda H, Hayashi Y, Shimamoto F, Yamakido M: Differences in histopathologic findings in restenotic lesions after directional coronary atherectomy or balloon angioplasty. Coronary Artery Dis 1998, 9:5-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBride W, Lange R, Hillis L: Restenosis after successful coronary angioplasty: pathophysiology and prevention. N Engl J Med 1988, 318:1734-1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Califf RM, Fortin DF, Frid DJ, Harlan WR, Ohman EM, Bengtson JR, Nelson CL, Tcheng JE, Mark DB, Stack RS: Restenosis after coronary angioplasty: an overview. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991, 17(Suppl. B):2B-13B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravanis MB, Roubin GS: Histopathologic phenomena at the site of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: the problem of restenosis. Hum Pathol 1989, 20:477-485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giraldo AA, Esposo OM, Meis JM: Intimal hyperplasia as a cause of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1985, 109:173-175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrester JS, Fishbein M, Helfant R, Fagin J: A paradigm for restenosis based on cell biology: clues for the development of new preventive therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991, 17:758-769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehra MR, Ventura HO, Stapleton DD, Smart FW: The prognostic significance of intimal proliferation in cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a paradigm shift. J Heart Lung Transplant 1995, 14:S207-S211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin GE, Ratliff MB, Hollman J, Tabei S, Phillips DF: Intimal proliferation of smooth muscle cells as an explanation for recurrent coronary artery stenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985, 6:369-375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jawien A, Bowen-Pope DF, Lindner V, Schwartz SM, Clowes AW: Platelet-derived growth factor promotes smooth muscle cell migration and intimal thickening in a rat model of balloon angioplasty. J Clin Invest 1992, 89:507-511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson CL, Raines E, Ross R, Reidy MA: Role of endogenous platelet-derived growth factor in arterial smooth muscle cell migration after balloon catheter injury. Arterioscler Thromb 1993, 13:1218-1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis SF, Yeung AC, Meredith IT, Charbonneau F, Ganz P, Selwyn AP, Anderson TJ: Early endothelial dysfunction predicts the development of transplant coronary artery disease at 1 year posttransplant. Circulation 1996, 93:457-462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakuta T, Currier JW, Hauderschild CC, Ryan TJ, Faxon DP: Differences in compensatory enlargement, not intimal formation, account for restenosis after angioplasty in the atherosclerotic rabbit model. Circulation 1994, 89:2809-2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post MJ, Borst C, Kuntz RE: The relative importance of arterial remodeling compared with intimal hyperplasia in lumen renarrowing after balloon angioplasty. Circulation 1994, 89:2816-2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savage MP, Douglas JS, Fischman DL, Pepine CJ, King SB, Werner JA, Bailey SR, Overlie PA, Fenton SH, Brinker JA, Leon MB, Goldberg S: Stent placement compared with balloon angioplasty for obstructed coronary bypass grafts. Saphenous vein de novo trial investigators. N Engl J Med 1997, 337:740-747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serruys PW, van Hout B, Bonnier H, Legrand V, Garcia E, Macaya C, Sousa E, van der Giessen W, Colombo A, Seabra-Gomes R, Kiemeneij F, Ruygrok P, Ormiston J, Emanuelsson H, Fajadet J, Haude M, Klugmann S, Morel MA: Randomised comparison of implantation of heparin-coated stents with balloon angioplasty in selected patients with coronary artery disease. Lancet 1998, 352:673-681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santoian EC, King SB, III: Intravascular stents, intimal proliferation and restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992, 19:877-879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai H, Masuda J, Sawa Y, Nakano S, Shirakura R, Shimazaki Y, Ogata J, Matsuda H: Neointima formation after vascular stent implantation. Spatial and chronological distribution of smooth muscle cell proliferation and phenotypic modulation. Arterioscler Thromb 1994, 14:1846-1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Bockxmeer FM, Mamotte CDS, Gibbons FR, Taylor RR: Apolipoprotein E4 homozygosity—a determinant of restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Atherosclerosis 1994, 110:195-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Bockxmeer FM, Mamotte CDS, Gibbons FA, Burke V, Taylor RR: Angiotensin-converting enzyme and apolipoprotein E genotypes and restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Circulation 1995, 92:2066-2071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishigami M, Swertfeger DK, Granholm NA, Hui DY: Apolipoprotein E inhibits platelet-derived growth factor-induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation by suppressing signal transduction and preventing cell entry to G1 phase. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:20156-20161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Geest B, Zhao Z, Collen D, Holvoet P: Effects of adenovirus-mediated human apoA-I gene transfer on neointima formation after endothelial denudation in ApoE-deficient mice. Circulation 1997, 96:4349-4356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Silva HV, Lauer SJ, Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Taylor JM: Apolipoproteins E and C-III have opposing roles in the clearance of lipoprotein remnants in transgenic mice. Biochem Soc Trans 1993, 21:483-487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rall SC, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW: Isolation and characterization of apolipoprotein E. Methods Enzymol 1986, 128:273-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindner V, Fingerle J, Reidy MA: Mouse model of arterial injury. Circ Res 1993, 73:792-796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou M, Sutliff RL, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Hoying JB, Haudenschild CC, Yin M, Coffin JD, Kong L, Kranias EG, Luo W, Boivin GP, Duffy JJ, Pawlowski SA, Doetschman T: Fibroblast growth factor 2 control of vascular tone. Nat Med 1998, 4:201-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N: Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science 1992, 258:468-471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setala K, Walsh A, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM, Breslow JL: Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 1992, 71:343-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahley RW: Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science 1988, 240:622-630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi C, Lee WS, Russell ME, Zhang D, Fletcher DL, Newell JB, Haber E: Hypercholeserolemia exacerbates transplant arteriosclerosis via increased neointimal smooth muscle cell accumulation. Studies in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Circulation 1997, 96:2722-2728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada N, Inoue I, Kawamura M, Harada K, Watanabe Y, Shimano H, Gotoda T, Shimada M, Kozaki K, Tsukada T, Shiomi M, Watanabe Y, Yazaki Y: Apolipoprotein E prevents the progression of atherosclerosis in WHHL rabbits. J Clin Invest 1992, 89:706-711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimano H, Ohsuga J, Shimada M, Namba Y, Gotoda T, Harada K, Katsuki M, Yazaki Y, Yamada N: Inhibition of diet-induced atheroma formation in transgenic mice expressing apolipoprotein E in the arterial wall. J Clin Invest 1995, 95:469-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyata M, Smith JD: Apolipoprotein E allele-specific antioxidant activity and effects on cytotoxicity by oxidative insults and beta-amyloid peptides. Nat Genet 1996, 14:55-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T: Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science 1995, 270:296-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashyap VS, Santamarina-Fojo S, Brown DR, Parrott CL, Applebaum-Bowden D, Meyn S, Talley G, Paigen B, Maeda N, Brewer HB: Apolipoprotein E deficiency in mice: gene replacement and prevention of atherosclerosis using adenovirus vectors. J Clin Invest 1995, 96:1612-1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hasty AH, Linton MF, Brandt SJ, Babaev VR, Gleaves LA, Fazio S: Retroviral gene therapy in apoE-deficient mice. ApoE expression in the artery wall reduces early foam cell lesion formation. Circulation 1999, 99:2571-2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Assadnia S, Rapp JP, Nestor AL, Pringle T, Cerilli GJ, Gunning WT, Webb TH, Kligman M, Allison DC: Strain differences in neointimal hyperplasia in the rat. Circ Res 1999, 84:1252-1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishida BY, Paigen B: Atherosclerosis in the mouse. Sparkes RS eds. Monographs in Human Genetics, 1989, vol. 12.:pp 189-222 Karger, New York [Google Scholar]

- 42.Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Eppig JT, Maltais LJ, Miller JC, Dietrich WF, Weaver A, Lincoln SE, Steen RG, Stein LD, Nadeau JH, Lander ES: A genetic linkage map of the mouse: current applications and future prospects. Science 1993, 262:57-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]