Abstract

An increase in illicit drug use in Northern Ireland may well have links to the resolution of political conflict, which started in the mid 1990s. Social issues, heretofore hidden, have emerged into the limelight and may be worsened by paramilitary involvement.1 Registered addicts in the four Health Board areas have shown an increase from 1997 with the greatest number resident within the Northern Board Area.2 As the prevalence of heroin use in Northern Ireland increased, the Department of Health and Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) commissioned a report, to recommend the development of substitute prescribing services.3 A case series of pregnancies was reviewed, within the Northern Board Area, where the mother was taking opioid substitution therapy. This resulted in baseline data of outcome for both mother and baby specific to a Northern Ireland population. The different medications for opioid substitution are also assessed. This information will guide a co-ordinated approach that involves obstetrician, anaesthetist, psychiatrist, midwife and social worker to the care of these high-risk pregnancies. Eighteen pregnancies were identified in the study period. Sixteen of these had viable outcomes. One was a twin pregnancy. Outcome data was therefore available for 17 infants.

Information was obtained regarding patients' social and demographic background, drug taking behaviour and substitution regimen. Antenatal and intrapartum care was assessed and infants were followed up to the time of hospital discharge.

INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse in pregnancy poses significant health risks to mother and fetus. Opioids are associated with an increased risk of low birth weight infants, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm delivery, neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).4 Neonatal withdrawal effects from heroin usually occur within 24 hours, those from methadone at 2 – 7 days. The signs and symptoms of withdrawal may affect all systems, particularly the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. Treatment involves regular feeding, correction of dehydration and drug therapy if required. A variety of agents, including morphine, methadone, chlorpromazine, phenobarbitone, diazepam and chloral hydrate have been used.5 Duration of symptoms varies (6 days to 5 weeks). Sudden infant death syndrome is two to three times greater in this group of infants.6

Abrupt withdrawal of opiates in pregnancy is also potentially dangerous with a risk of miscarriage, stillbirth and preterm labour. Pregnancy, however, provides motivation for lifestyle change and many women want to stop illicit drug use in the interests of their unborn babies.7 As healthcare providers working within a multidisciplinary setting we have a unique opportunity to address some aspects of this drug-taking behaviour when a woman is pregnant.

Methadone is the preferred substitution drug for use in either maintenance treatment or detoxification during pregnancy. It is a synthetic opioid with a long half-life, so may be given once daily. It is available in oral solution at 1mg/ml. It is usually prescribed weekly and dispensed daily in the community. It will completely remove withdrawal symptoms but does not induce the same “high” the opiate user finds in heroin. Maternal blood concentrations are relatively stable, reducing some of the intoxicating “swings” to which the fetus of a heroin-addicted mother is exposed. Maternal use of methadone may be associated with reduced fetal growth (a common problem in heroin addicts), but there is no evidence of teratogenicity.8 Patients are usually stabilised on methadone in the first and third trimesters. If withdrawal is an option, this is best done in the second trimester. The aim is to reduce methadone to 15mg or less by the delivery date to reduce the risk of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS).

Buprenorphine (Subutex) is an opioid partial agonist. It is increasingly used as an opioid substitute in the UK since being licensed here in 1999. It is given as a once-daily sublingual tablet at an initial dose of 0.8 to 4mgs but there is limited experience of its use in pregnancy in the UK. Case series (particularly from Europe) have been reassuring and rates of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome are slightly reduced overall (range from 47% to 72% of infants).9,10,11,12,13 It is suggested that the severity and duration of NAS is also improved. Because of its partial agonist activity there is some concern regarding analgesia use with buprenorphine. These patients require careful planning of analgesia for labour. It causes less enzyme induction than methadone and may be a better alternative for patients requiring other medication e.g. anticonvulsants.

Dihydrocodeine is not licensed as an opioid substitution treatment but has been used to wean patients off stronger opioids. There is a growing concern about its use in this respect as repeated tablet taking throughout the day – (necessary due to the drug's short half-life) may reinforce patterns of drug-taking behaviour and prohibit change.14

OBJECTIVES

From a case series of pregnancies, where the mother was taking opioid substitution medication to:

Produce baseline data of outcome for both mother and baby specific to a Northern Ireland Maternity Unit.

Review the possible treatment options for opioid substitution in pregnancy.

Produce guidelines for use in our maternity unit: to optimise patient care and provide a set of standards for future audit and training.

METHODS

Antrim Hospital Maternity Unit delivers approximately 2300 babies per annum. Cases for inclusion in the series were identified using NIMATS (Northern Ireland Maternity System) computer database of all pregnancies delivered from 1st January 1995 until 31st August 2004. The search criteria documented maternal medications under the headings “Drug Abuse”, “Heroin”, “Methadone” and “Detox. Programme.” The cases highlighted were then cross-referenced with patients registered and treated with input from the local addiction unit based in Holywell Psychiatric Hospital.

Management of these pregnancies is currently based on the 1999 Department of Health report – “Drug Misuse and Dependence – Guidelines on clinical management”. The multidisciplinary team consists of: addiction psychiatrist, obstetrician, GP, social services childcare team, obstetric anaesthetist, neonatologist and midwives (community and hospital). The addiction team works closely with the obstetric team, seeing patients in whatever setting is most appropriate for the individual's need. A pre-birth multidisciplinary meeting takes place between 32 and 36 weeks gestation to discuss the likely childcare management plan following delivery. After the delivery a further meeting takes place to activate the plan and review the overall situation.

From the patients’ charts, information was obtained regarding:

Patients demographic and social details and drug-taking history

Obstetric history (past and present)

Labour/delivery details

Infant details, including admission to neonatal unit (NNU)

Social Services involvement

RESULTS

Antenatal Care / Labour and Delivery

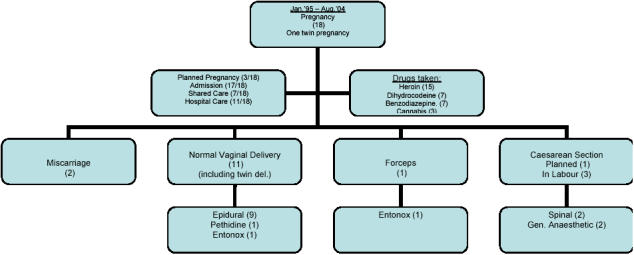

Figure 1 outlines the pregnancies identified, drugs of abuse, mode of delivery and analgesia required in labour. Routine antenatal screening bloods (full blood picture, Treponemal antibody tests, blood group and hepatitis B antigen) were normal except in one case that had low titres of Anti-E and –c antibodies. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) screening was introduced in 2003/4.The more recent cases in this series (four patients) were offered routine screening for Hepatitis C and HIV. All tested negative. There was good overall compliance with antenatal care.

Fig 1.

Antenatal Care/Mode of Delivery/Analgesia 18 pregnancies from January 1995 – August 2004.

Hospital admissions to either Antrim Area Hospital maternity unit or Holywell Hospital Addictions Unit were frequent in 17/18 cases. These were for significant periods of time to cope with social issues and stabilisation of substitution therapy (range 3 – 18 weeks with an average stay of 6 weeks).

Most abused more than one drug (mean 2.4 per person). For those who used heroin, most started this before 22 years of age (range 15 – 36 yrs.)

Of the 15 patients who laboured, seven had spontaneous onset of labour (3 preterm) and labour was induced in the remaining 8 patients (all at term). The reasons for induction of labour were: to achieve a planned delivery (5 cases), post-dates (2 cases) and suspected intrauterine growth retardation (one case).

Social and demographic details

See Table I.

Table I.

Social/demographic details

| Social/Demographic details | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Unemployed | 16/18 (89%) |

| Housing exec. Accommodation | 18/18 (100%) |

| Single parents | 16/18 (89%) |

| Cigarette smokers | 18/18 (100%) |

| History of depressive illness | 5/18 (28%) |

| History of sexually transmitted infection | 2/18 (11%) |

| Documented domestic violence | 1/18 (5.5%) |

Information was available for 14 partners, 13 of whom were known current or recent heroin users.

Substitution Treatment

Methadone was taken as substitution treatment in 14 pregnancies (10 - 40mgs at maximum dosage with a mean dose of 25mgs). Two patients discontinued methadone in the third trimester and three further patients discontinued the drug in the early postnatal period.

Buprenorphine (Subutex) was used in two pregnancies, the patients taking 8 and 14 mg throughout.

Dihydrocodeine was used in two pregnancies, the patients taking 4 and 6 tablets daily. One patient reduced the dose postnatally.

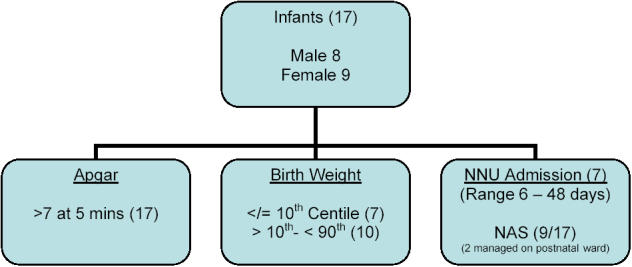

Figure 2 outlines the outcome of the 17 neonates. Seven were admitted to the neonatal unit (4 at birth and 3 on day one). All of these were diagnosed with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) +/− prematurity, infection and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Whilst in the NNU two babies required supportive treatment only with fluids, antibiotics, support with feeding and phototherapy. Seven babies in total required treatment with choral hydrate for NAS .The twins, whose mother had been on 40mgs methadone daily in pregnancy, also needed treatment with phenobarbitone (intravenous then oral).

Fig 2.

Outcome of 17 Neonates (Apgar score / Birth Weights / Neonatal Unit admission)

All babies eventually went home with their mothers (most with supportive care from grandparents). All patients had social services support from the booking visit until postpartum. 2/17 babies are on the “at-risk” register as potential for neglect. Two mothers were admitted to prison in the early postnatal period.

DISCUSSION

The number of heroin addicts in Northern Ireland is increasing and with it a population of vulnerable women. In this series, all male partners (for whom we had information) were known current or recent heroin users and this is often the path that leads these women into this pattern of behaviour.

The results highlight social circumstances typical of this group. While most do not plan a pregnancy in these circumstances, the pregnancy itself can provide sufficient stimulus to attempt lifestyle changes for the benefit of the unborn child. These high risk pregnancies require skilled multidisciplinary care to optimise the outcomes for both mother and baby.

The absence of any Hepatitis B or C positive patients in this group is unusual. Some of this data is from cases in the late 1990's when heroin abuse was relatively new to Northern Ireland. A small number of Hepatitis C positive cases have been identified more recently, since this series was compiled. Hepatitis B immunisation is now routinely offered to registered addicts.

The majority of these patients require antenatal hospital admission and often for many weeks. This has repercussions for bed occupancy and staffing in both obstetric and psychiatric units. Many factors exist in these pregnancies that contribute to the finding of small for gestational age infants (41% </= 10th centile). One study has tried to quantify the weight reduction due to opiates alone, concluding a 489gm reduction in infants of pregnant heroin users, 279gm reduction in methadone users and 557gm reduction in those who take both in pregnancy.15

53% (9/17) of infants in this series ultimately had a diagnosis of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS). This value compares favourably with the quoted incidence from literature (55-94%) and probably reflects the composition of our population who: attended well, had long periods of inpatient treatment and were maintained on relatively low doses of substitution treatment. The numbers in the study are too small to draw any more definite conclusions.

Social services have a large input with these families and see these women frequently throughout pregnancy and on discharge from hospital. It is gratifying that all the infants in this group were eventually able to go home with their mothers, but understand the need for ongoing support and supervision provided by community services and the local child care team.

CONCLUSIONS

Heroin addiction is increasingly prevalent in Northern Ireland (and specifically in the Northern Area Health Board). The limited experience gained in the management of these vulnerable patients has allowed the Antrim Hospital Maternity Unit to develop care guidelines (Appendix I). Other Health Areas have a much wider knowledge of the problems of such care and we are grateful to the resource pack produced by DrugScope/NHS Lothian. Their model care pathway aided the design of our guidelines.16 These will provide a framework for clinical audit, education and staff training and help to optimise outcomes for these mothers and babies.

Adequate follow-up for this group, where 53% (9/17) of infants had Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and 12% (2/17) are on the children's at-risk register, is a priority.

Acknowledgments

Drug Scope / NHS Lothian for permission to use ‘Substance misuse in pregnancy – A resource book for professionals’ as a template for Antrim Maternity Unit Guideline development.

We gratefully acknowledge verbal communication with Dr Mary Hepburn, BSc, MD, MRCGP, FRCOG - Senior Lecturer in Women's Reproductive Health, Glasgow University, Department of Obstetrics/Gynaecology and Social Policy/Social Work, and an Honorary Consultant Obstetrician & Gynaecologist at the Princess Royal Maternity Hospital in Glasgow.

Appendix I.

Substance Misuse in pregnancy - Management Guidelines

| Pre-conception Care | Ideally planned pregnancies Stabilised on opioid substitute if appropriate | Confirm preg. (GP, FPC etc.) |

| Folic Acid 400mcg (preconception – 12 weeks) | ||

| Early antenatal booking | ||

| Antenatal Booking (by 12 weeks) | Ultrasound scan – Viability, gestation, dates | Obtain informed consent to allow info. to be shared with involved health professionals |

| Antenatal blood screening – inc. HIV, Hep. B and C | ||

| Document all drug use – | Risk assessment – | |

| • Smoking/Alcohol | • Past ob. / med. history | |

| • Prescribed med. – Include name and tele. no. of prescribing doctor and dispensing chemist and dose and frequency of meds. dispensed | • Physical/mental health | |

| • Illicit drug use: what used, how often, how much, route of admin, duration of use, pattern since pregnant? | • Social needs | |

| • Domestic violence | ||

| • Partner's drug use | ||

| Decide Shared/Hospital antenatal care – Document planned reviews | ||

| Care Plan drawn up involving | ||

| • Maternity care | ||

| • Primary care | ||

| • Addiction services | ||

| • Family/Social care | ||

| Hospital reviews | Fetal Anomaly scan (20-22 weeks) | Parent education classes |

| Discuss poss. of NAS | ||

| Third trimester scan(s) for growth (28, 34 weeks) | Discuss analgesia for labour | |

| Check if venous access diff. | ||

| Arrange IOL if reqd. for planned del. | ||

| Multidisciplinary meeting | Case conference | Pre-birth to plan services – usually 32-36 weeks |

| Intrapartum care | Inform obstetric/paediatric staff once admitted in labour | Intrapartum monitoring – risk of plac. insuff., IUGR, fetal distress, meconium staining |

| Substitution therapy to be given as usual in labour | ||

| Analgesia – opioids can be given but dose/freq. may need increased | Do NOT use Naloxone for resp. depression in neonate – supportive measures/ventilate if necessary | |

| Postnatal Care (in Hospital) | Keep Mum and baby together if poss. | Encourage to stay in hosp. for minimum 3 days after del. to observe baby for signs of NAS |

| Breastfeeding encouraged unless HIV + or large quantities of stimulant drugs | Contraception – Discuss, document and implement early | |

| Pre-discharge case conference | Child care/protection issues | Clear communication to all healthcare professionals for follow-up services |

| Organise family support | ||

| Medication review | ||

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Higgins K, Percy A, McCrystal P. Secular trends in substance use: the conflict and young people in Northern Ireland. J Soc Issues. 2004;60(3):485–506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Statistics from the Northern Ireland drug misuse database: 1 April 2003–31 March 2004. Available from: http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/drug_misuse_mar04.pdf.

- 3.McElrath K. Review of research on substitute prescribing for opiate dependence and implications for Northern Ireland. Belfast: Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety; 2003. Available from: http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/substitute_prescribing_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klenka HM. Babies born in a district general hospital to mothers taking heroin. BMJ. 1986;293(6549):745–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6549.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson K, Gerada C, Grennough A. Treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(1):F2–5. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.1.F2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward SL, Bautisa D, Chan L, Derry D, Lisbin A, Durfee MJ, et al. Sudden infant death syndrome in infants of drug abusing mothers. J Pediatr. 1990;117(6):876–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepburn M. Drug use in pregnancy. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;49(1):51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoegerman G, Scholl S. Narcotic use in pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 1991;18(1):51–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer G, Etzersdorfer P, Eder H, Jagsch R, Langen M, Weninger M. Buprenorphine maintenance in pregnant opiate addicts. Eur Addict Res. 1998;4(Suppl 1):32–6. doi: 10.1159/000052040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer G, Johnson RF, Eder H, Jagsch R, Peternell A, Weninger M, et al. Treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women with buprenorphine. Addiction. 2000;95(2):239–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95223910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jernite M, Vivelle B, Escande B, Brettes JP, Messer J. [Buprenorphine and Pregnancy. Analysis of 24 cases.] Arch Pediatr. 1999;6(11):1179–85. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(00)86300-9. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RE, Jones HE, Jasinski DR, Svikis DS, Haug NA, Jansson LM, et al. Buprenorphine treatment of pregnant opioid-dependent women: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63(1):97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohrmeister K, Bernert G, Langer M, Fischer G, Weninger M, Pollack A. Opiate addiction in gravidity – consequences for the new-born. Results of an interdisciplinary treatment concept. Z Geburtshilfe Neonato. 2001;205:224–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-19054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swadi H, Wells B, Power R. Misuse of dihydrocodeine tartrate (DF118) among opiate addicts. BMJ. 1990;300(6735):1313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6735.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulse GK, Milne E, English DR, Homan CD. The relationship between maternal use of heroin and methadone and infant weight. Addiction. 1997;92:1571–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Substance misuse in pregnancy: a resource book for professionals. Lothian, Scotland: Drugscope and UK National Health Service, Scotland; 2005. [Google Scholar]