Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness among the elderly in Western countries. Genetic factors, age, cigarette smoking, nutrition, and exposure to light have been identified as AMD risk factors. In this study, we investigated the association between ApoE C112R/R158C single nucleotide polymorphisms (which determine the E2, E3, and E4 isoforms) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and the mechanism underlying the association. Genomic DNA was extracted from 133 clinically screened controls, 94 volunteers with a younger mean age, 120 patients with advanced AMD, and 40 archived ocular AMD slides for single nucleotide polymorphism typing. The effects of recombinant ApoE isoforms on CCL2 (a chemokine), CX3CR1 (a chemokine receptor), and VEGF (a cytokine) expression in cultured human retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells were tested and serum cholesterol profiles of the clinically screened subjects were analyzed. ApoE112R (E4) distribution differed significantly between AMD patients and controls. ApoE112R allele frequency was 10.9% in the AMD group when compared with 16.5% in the younger controls and 18.8% in the clinically screened controls. The pathologically diagnosed archived AMD cases had the lowest allele frequency of 5%. No significant differences in ApoE158C (E2) distribution were observed among the groups. A meta-analysis of 8 cohorts including 4,289 subjects showed a strong association between AMD and 112R, but not 158C. In vitro studies found that recombinant ApoE suppresses CCL2 and VEGF expression in RPE cells. However, the E4 isoform showed more suppression than E3 in both cases. These results further confirm the association between ApoE112R and a decreased risk of AMD development. The underlying mechanisms may involve differential regulation of both CCL2 and VEGF by the ApoE isoforms.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration; apolipoprotein E, single nucleotide polymorphism; genetic susceptibility; cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness among the elderly in Western countries [la Cour et al., 2002]. AMD is a significant health problem in the United States, with a current estimate of roughly 1.75 million persons with advanced AMD in the general population. By the year 2020, it is estimated that ∼2.95 million people will have developed AMD [Friedman et al., 2004].

The etiology of AMD remains elusive. To date, age, cigarette smoking, nutrition, and exposure to light have been identified as AMD risk factors [Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group, 2000, 2001; Seddon et al., 2001; Husain et al., 2002; Hyman and Neborsky, 2002]. Various studies also indicate a significant genetic contribution to AMD risk [Tuo et al., 2004a]. For example, it has been reported that advanced AMD is more prevalent in Caucasian populations when compared with other races that possess higher levels of uveal pigmentation and skin melanin [Friedman et al., 1999; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group, 2000]. Furthermore, ∼20% of AMD patients report having a positive family history [Klaver et al., 1998b; de Jong et al., 2001]. The higher occurrence of AMD among monozygotic twins and first-degree relatives of AMD patients when compared with spouses and unrelated individuals also indicates a significant genetic component in AMD risk [Meyers et al., 1995; Seddon et al., 2005]. A few studies have been able to demonstrate an association between AMD and various single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [Tuo et al., 2004a; Edwards et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005; Tuo et al., 2006].

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a multiple function protein highly expressed in the liver, brain, and retina [Anderson et al., 2001; Ribalta et al., 2003]. The ApoE gene is known to be polymorphic. SNPs at positions 112 (rs no. 429358) and 158 (rs no. 7412) determine three major isoforms: E2 (112C, 158C), the most common E3 (112C, 158R), and E4 (112R, 158R). These isoforms vary greatly in terms of protein structure and function [Zannis, 1986; Jarvik, 1997; Laws et al., 2003]. The ApoE E4 isoform is correlated with elevated cholesterol concentrations and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [Mahley and Huang, 1999; Smith, 2000; Ribalta et al., 2003]. The E4 isoform is also associated with various neurodegenerative diseases, most notably Alzheimer Disease (AD) [Chapman et al., 2001; Laws et al., 2003]. Cardiovascular disease, AD, and AMD share a number of similar pathological features [Klaver et al., 1998a, 1999; Mullins et al., 2000; Dentchev et al., 2003]. ApoE is also a ubiquitous component of soft drusen, a hallmark of early AMD development [Anderson et al., 2001]. Moreover, various clinical signs of retinal degeneration are mimicked in Apo(*)E3-Leiden knockout mice that carry a dysfunctional form of human ApoE-E3 [Dithmar et al., 2000; Kliffen et al., 2000].

Investigators have attempted to determine the role of ApoE in AMD development and pathogenesis [Klaver et al., 1998a; Souied et al., 1998; Baird et al., 2004; Zareparsi et al., 2004]. Interestingly, the E4 allele has been reported by several independent groups as being significantly less prevalent among AMD cases when compared with the corresponding control populations [Klaver et al., 1998a; Souied et al., 1998; Simonelli et al., 2001; Baird et al., 2004; Zareparsi et al., 2004]. The E4 polymorphism is associated with a protective effect against AMD, while the E2 allele is weakly associated with a slightly increased risk for developing late AMD (see our meta-analysis).

Although the majority of previous reports are in agreement, there are studies that have challenged and narrowed the proposed protective effect of the ApoE E4 allele [Schmidt et al., 2000; Schultz et al., 2003]. The aim of this present study was first to verify the association between the ApoE SNPs and AMD by using an independent sample set, implementing a multiple group design, employing SNP typing with standard DNA controls, and by performing a meta-analysis of relevant published data. Functional SNP studies determining the effects of recombinant ApoE isoforms on the expression of CCL2 (a chemokine), CX3CR1 (a chemokine receptor), and VEGF (a cytokine) in cultured human retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) cells were performed to explore the potential mechanisms by which the ApoE SNPs influence AMD pathogenesis. Lastly, serum cholesterol profiles of the clinically screened subjects were analyzed to elucidate the possible correlation of ApoE isoforms, lipid levels, and AMD development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

This multiple case–control study included two AMD groups and two normal control groups. Each participant signed the Informed Consent that was part of the protocol approved by the NEI Institutional Review Board. This research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Only advanced AMD cases were included in this study. A clinical diagnosis of advanced AMD was defined by geographic atrophy involving the center of the macula and/or choroidal neovascularization with drusen in at least one eye. Stereoscopic fundus photographs of the optic disk and macula were obtained for all AMD patients. These patients are referred to as the clinically diagnosed AMD group (CD AMD). The recruited control subjects were all older than 50 years of age and clinically defined by an absence of drusen or less than 5 small drusen (<63 μm) in the center of the macula and an absence of all other retinal disease affecting the photoreceptors and outer retinal layers. Healthy blood donors (BD) who did not receive a clinical eye examination served as another control group to obtain information on SNP frequencies in a population younger than the average age of AMD onset. This group is referred to as the BD controls.

Archived paraffin-embedded ocular sections were obtained from 40 pathologically diagnosed advanced-stage AMD patients (PD AMD). Twenty-three of the 40 cases were classified as neovascular AMD characterized by loss of photoreceptors and RPE alterations within the macular region and subretinal neovascular fibrous tissue with or without hemorrhage, exudate, and disciform scar. The remaining 17 cases were classified as areolar or dry AMD cases without neovascularization and characterized by a loss of photoreceptors, RPE atrophy or hypotrophy, the presence of diffuse confluent drusen or large drusen, calcification, and fibroglial scar in the macula.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted and isolated from venous whole blood (10 mL) collected from the study subjects using a QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Either laser-capture microscopy (Pix-Cell II; Arcturus, Mountain View, CA) or manual microdissection was used to procure cells from the archived paraffin-embedded ocular sections. Extracted DNA from these cells was then subjected to whole genome amplification using the GenomiPhi™ DNA amplification kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for subsequent SNP typing.

Construction of DNA Standards

Standard DNA SNP templates were made to serve as SNP typing controls. Genomic DNA of heterozygous ApoE C112R or R158C was PCR-amplified using the primers 5′-GGGCACGGCTGTCCAA-3′ and 5′-ATAAGAATTCCCCGGCCTGGTACACT-3′. The 237-bp PCR fragment was inserted in to the pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The ligation product was transformed to JM109 high efficiency competent cells (Promega). Colonies containing ApoE 112C, 112R, 158R, and 158C homozygotes were confirmed by direct sequencing. Plasmid DNA was extracted from the colonies corresponding to each allele to serve as the specific allele standards. The combination of homozygote plasmids served as the heterozygous standard.

SNP Typing

The typing of ApoEC112R was performed using a PCR-RFLP technique. A 213 base-pair DNA fragment containing ApoE112 was PCR amplified using the following primers: 5′-TGATGGACGAGACCATGAAG-3′ and 5′-CAGCTCCTCGGTGCTCTG-3′. RFLP analysis was conducted using the enzyme Hha1.

ApoER158C was typed using Real-time PCR allelic discrimination assays provided by the Assay-by-Demand℠ service of Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Real-time fluorescence detection was performed. Genotypes were determined based on the fluorescence intensities of FAM and VIC, with FAM signaling ApoE158C and VIC ApoE158R. Standard DNA controls for both alleles and a heterozygous control were included on each genotyping plate in both the RFLP and Real-time PCR assays.

In Vitro Functional Studies

Human ARPE-19 cells were separately exposed to 40 μg/ml of ApoE E3 and E4 recombinant proteins (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 24 hr. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated (100 ng/ml, Salmonella typhimurium LPS endotoxin; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and untreated control cells were processed in a similar fashion. Cells were subjected to RNA extraction. Real-time PCR for determining gene expression was performed using a Stratagene M×3000™ System and Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The primers for CCL2 and CX3CR1 were synthesized by Superarray and supplied as an RT2 Real-Time™ Gene Expression Assay Kit (Superarray, Fredrick, MD). For the internal control, β-actin was amplified using primers 5′-CCCAGCACAATGAAGATCAA-3′ and 5′-ACATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGAC-3′. Following PCR, a thermal melt profile was performed for amplicon identification. Each sample was analyzed at least twice. The comparative Ct method was used for relative quantification and statistical analysis of the fold changes to present the data graphically. The culture media were collected for ELISA assay of CCL2 and VEGF using commercially available kits (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA).

Serum Profiling

Clinically screened cases and controls fasted for a period of 12 hr before their blood draw. Total serum cholesterol was evaluated, with the normal values ranging from 100 to 200 mg/dl.

Statistical Analysis

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between ApoE112 and ApoE158 was analyzed using the web-based SNPAnalyzer (http://www.istech21.com/phar/phar_a01.html). The normalized disequilibrium coefficient D′ was used as the parameter for determining the strength of association between the SNPs. With the range of possible D′ values lying between −1 and 1, a greater association (coinheritance) was established when the D′ value was closer to 1.

The χ2 test was performed to compare the carrier and allele frequencies and abnormal rates of the cholesterol level of the cases and controls. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was also tested using the χ2 test with 1 degree of freedom. A P value of < 0.025 was considered significant following Bonferroni correction [McIntyre et al., 2000]. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and an estimation of confidence intervals was made based on the unmatched case–control design [Bland and Altman, 2000]. A t-test was used to compare differences in cholesterol levels between groups.

RESULTS

All enrolled subjects were Caucasians of non-Hispanic descent recruited from the greater Washington, DC area. One hundred twenty sporadic advanced AMD patients (CD AMD), 94 random unscreened BD controls, and 133 screened normal controls were included in this study. Out of the advanced AMD patients, 79 had neovascular (wet) AMD. The remaining 41 had areolar (dry) AMD. Forty archived slides of PD AMD cases also were included in the study. The majority of the sources for these slides were Caucasian. The AMD case and screened control groups were matched as closely as possible for both age and gender. The demographics of these four study groups are summarized in Table I.

TABLE I.

Demographic Summary of Study Groups

| N | Female (%) | Mean age | Past or current smokers (%) | Caucasian (%) | Wet AMD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened control | 133 | 76 (57.1) | 69.7 ± 8.4 | 62 (46.6) | 133 (100.0) | N/A |

| Random control | 94 | 32 (34.0) | 35.1 ± 9.1 | NA | 94 (100.0) | N/A |

| Clinical AMD | 120 | 66 (55.0) | 75.2 ± 7.2 | 72 (60.0) | 120 (100.0) | 79 (65.8) |

| Archived AMD | 40 | 20 (74.1)a | 82.8 ± 9.2 | NA | 26 (96.3)a | 23 (57.5) |

NA, not available; N/A, not applicable.

Values excluding data from 13 specimens with unknown sex and race.

Among the groups evaluated for the ApoE 112 and 158 SNPs, no significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was noted. LD between ApoE 112 and 158 was incomplete with a D′ of −1 overall, suggesting that no linkage association exists between these two SNPs.

SNP-type distribution analyses showed a decreased prevalence of 112R carriers and alleles among AMD cases when compared with the controls (Tables II and III). Statistically significant differences in both 112R carrier and allele frequencies were observed in the total controls when compared with the total AMD cases, with 0.51 and 0.53 ORs, respectively (P < 0.01; Tables II and III). No significant differences were detected in 158C carrier and allele frequencies between the AMD cases and controls (Tables II and III). In the CD AMD group, the OR for the 112R carriers (112C/R + 112R/R vs. 112C/C) was 0.61 when compared with that for the screened controls (Table II). We observed a lower OR of 112R carriers for the CD AMD cases vs. the screened controls than vs. the BD controls (0.61 vs. 0.67). The lowest OR (0.21) for the 112R carriers was observed in the PD AMD group in comparison with the screened controls (Table II). Analysis of allele frequencies yielded a similar pattern (Table III). These results may be due to the PD AMD cases having a more definitive diagnosis when compared with that of the CD AMD patients. The assumption that a certain percentage of BD controls will later develop AMD in advancing age is also consistent with this data.

TABLE II.

Carrier Frequencies of ApoE C112R and R158C

|

ApoE112 |

ApoE158 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | C/C |

C/R (%) |

R/R (%) |

C/R+R/R OR (CI) |

X2/P | R/R |

R/C (%) |

C/C (%) |

R/C+C/C OR (CI) |

X2/P | |

| All controls | 227 | 152 | 69 (30.4) | 6 (2.6) | 182 | 44 (19.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||||

| Controls | 133 | 87 | 42 (31.6) | 4 (3.0) | 103 | 30 (22.6) | 0 | ||||

| Blood donors | 94 | 65 | 27 (28.7) | 2 (2.1) | 79 | 14 (14.9) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| All AMD | 160 | 127 | 31 (19.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.51 (0.32–0.79) | 7.12/0.009 | 102 | 18 (15.0) | 0 | 0.85 (0.51–1.42) | 0.58/0.45 |

| CD AMD | 120 | 91 | 27 (22.5) | 2 (1.7) | 0.61 (0.35–1.03)a | 3.20/0.07 | 102 | 18 (15.0) | 0 | 0.79 (0.39–1.32)a | 1.16/0.29a |

| 0.67 (0.37–1.22)b | 1.7/0.12 | 0.98 (0.48–1.95)b | 0.01/0.94b | ||||||||

| PD AMD | 40 | 36 | 4 (10) | 0 | 0.21 (0.06–0.63)a | 8.52/0.004 | |||||

In comparison with screened controls.

In comparison with blood donors.

TABLE III.

Allele Frequencies of ApoE C112R and R158C

|

ApoE112 |

ApoE158 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alleles | C | R (%) | OR (CI) | X2/P | R | C (%) |

C carrier OR (CI) |

X2/P | |

| All controls | 454 | 373 | 81 (17.8) | 408 | 46 (10.1) | ||||

| Controls | 266 | 216 | 50 (18.8) | 236 | 30 (11.3) | ||||

| Blood donors | 188 | 157 | 31 (16.5) | 172 | 16 (8.5) | ||||

| All AMD | 320 | 285 | 35 (10.9) | 0.53 (0.33–0.80) | 7.4/0.007 | 222 | 18 (7.5) | 0.89 (0.49–1.40) | 0.44/0.51 |

| CD AMD | 240 | 209 | 31 (12.9) | 0.63 (0.43–1.05)a | 3.18/0.08a | 222 | 18 (7.5) | 0.82 (0.40–1.30)a | 1.03/0.31a |

| 0.68 (0.44–1.19)b | 1.69/0.19b | 1.01 (0.51–1.03)b | 0.01/0.94b | ||||||

| PD AMD | 80 | 76 | 4 (5) | 0.23 (0.09–0.69)a | 8.24/0.004 | ||||

In comparison with screened controls.

In comparison with blood donor controls.

A meta-analysis of 8 independent published studies based primarily on Caucasian populations examined a total of 1,925 AMD patients and 2,364 normal controls (Table IV). The OR, CI, and P values for ApoE E2 and E4 were calculated for this pooled data set (Table IV). Five out of the 8 studies reported an association between E4 and a reduced risk of AMD using P < 0.05 as the significance criterion. The ORs ranged from 0.38 to 0.82. Pooling the data did not dramatically change the OR; however, the statistical power of this reported association increased (P < 0.0001).

TABLE IV.

Meta-Analysis of Independent AMD-ApoE Association Studies in Caucasian Populations

| Control Allele no (%) |

AMD Allele no (%) |

OR (CI) | X2/P | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klaver et al. [1998a] | E2 | 162 (9.0) | 22 (12.5) | 1.44 (0.74–2.83) | 2.33/0.13 | Cases and controls derived from the population-based Rotterdam Study in the Netherlands. |

| E3 | 1,357 (75.3) | 142 (80.6) | ||||

| E4 | 281 (15.6) | 12 (6.8) | 0.39 (0.17–0.92) | 9.8/0.002 | ||

| Total | 1,800 | 176 | ||||

| Souied et al. [1998] | E2 | 21 (6.2) | 23 (9.9) | 1.65 (0.89–3.06) | 2.58/0.11 | Unrelated patients with exudative AMD compared to gender and age-matched controls. |

| E3 | 265 (78.9) | 192 (82.8) | ||||

| E4 | 50 (14.9) | 17 (7.3) | 0.45 (0.25–0.81) | 7.53/0.006 | ||

| Total | 336 | 232 | ||||

| Schmidt et al. [2000] | E2 | 60 (8.1) | 40 (8.7) | 1.09 (0.71–1.65) | 0.15/0.70 | Familial and sporadic cases of AMD were pooled as well as analyzed separately. Significant differences in age and gender at time of exam. However, estimated age/sex-adjusted ORs were made via logistic regression analysis. |

| E3 | 575 (77.3) | 366 (79.6) | ||||

| E4 | 109 (14.6) | 54 (11.7) | 0.77 (0.55–1.10) | 2.06/0.15 | ||

| Total | 744 | 460 | ||||

| Simonelli et al. [2001] | E2 | 2 (2) | 17 (9.8) | 5.20 (1.17–22.99) | 5.76/0.02 | Italian population, age-matched controls. |

| E3 | 89 (90.9) | 152 (87.3) | ||||

| E4 | 7 (7.1) | 5 (2.9) | 0.38 (0.12–1.25) | 2.71/0.10 | ||

| Total | 98 | 174 | ||||

| Schultz et al. [2003] | E2 | 56 (8.8) | 68 (9.4) | 1.08 (0.74–1.56) | 0.16/0.69 | Familial and unrelated AMD patients were included. Here, the groups are pooled. Trends of E4 in protection were found. |

| E3 | 497 (77.7) | 575 (79.2) | ||||

| E4 | 87 (13.6) | 83 (11.4) | 0.82 (0.59–1.13) | 1.46/0.23 | ||

| Total | 640 | 726 | ||||

| Baird et al. [2004] | E2 | 17 (6.9) | 50 (9.9) | 1.48 (0.84–2.63) | 1.84/0.17 | All participants were Anglo-Celtic in origin with all four grandparents born in either the UK or Ireland. |

| E3 | 185 (75.2) | 396 (78.6) | ||||

| E4 | 44 (17.9) | 58 (11.5) | 0.68 (0.44–1.03) | 3.84/0.05 | ||

| Total | 246 | 504 | ||||

| Zareparsi et al. [2004] | E2 | 33 (8.0) | 116 (9.2) | 1.16 (0.77–1.74) | 0.34/0.56 | White patient cohort recruited from a single center. Subsequent OR calculations were adjusted for both gender and age. |

| E3 | 320 (78.0) | 1,022 (81.2) | ||||

| E4 | 57 (14) | 120 (9.5) | 0.47 (0.33–0.66) | 4.78/0.03 | ||

| Total | 410 | 1,258 | ||||

| Current study | E2 | 46 (10.1) | 18 (5.6) | 0.89 (0.49–1.40) | 0.44/0.51 | Multiple case–control groups including advanced AMD cases only. |

| E3 | 327 (72.0) | 267 (83.5) | ||||

| E4 | 81 (17.9) | 35 (10.9) | 0.53 (0.33–0.80) | 7.4/0.007 | ||

| Total | 450 | 320 | ||||

| Pooled data | E2 | 397 (8.3) | 351 (9.1) | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) | 1.9/0.17 | |

| E3 | 3,615 (76.5) | 3,109 (80.8) | ||||

| E4 | 716 (15.2) | 390 (10.1) | 0.63 (0.55–0.71) | 48.4/0.000 | ||

| Total | 4,874 | 3,850 |

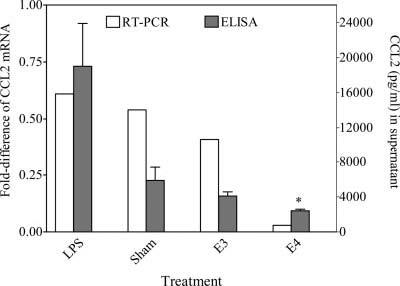

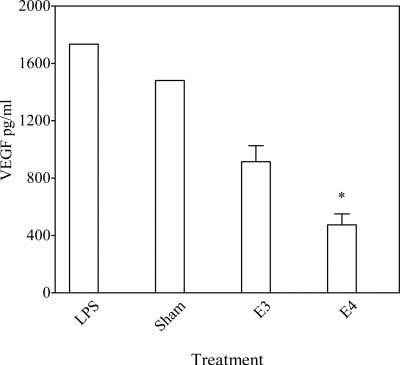

To elucidate the possible mechanisms underlying the association between ApoE isoforms and AMD, the effects of the E3 and E4 isoforms on the expression of selected chemokines, chemokine receptors, and cytokines was evaluated in RPE cells. The in vitro experiments indicated that the CCL2 levels in normal and LPS-stimulated RPE cells were 5,874 and 19,012 pg/ml, respectively (Fig. 1). Recombinant ApoE suppressed the expression of the CCL2 transcript and protein in RPE cells. However, the E4 isoform showed a stronger suppression of CCL2 than E3 (Fig. 1). RPE cell expression of VEGF following ApoE recombinant incubation showed the same pattern as that of CCL2 (Fig. 2). The E4 isoform had a stronger suppression of VEGF than E3. No distinct expression of the CX3CR1 transcript was observed in RPE cells incubated with either E3 or E4 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Fold changes (shown are the means from 2 independent experiments calculated from calibration curves) in mRNA abundance (relative to β-actin) and CCL2 protein (mean ± SD from 4 independent experiments) in the medium of RPE cells incubated with either the E3 or E4 isoform. Significance established at P < 0.05. *In comparison with E3 treatment.

Fig. 2.

VEGF protein (mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments) in the RPE cell culture medium of RPE cells incubated with either the E3 or E4 isoform. Significance established at P < 0.05. *In comparison with E3 treatment.

We also analyzed the correlation between ApoE112R and serum cholesterol levels (Tables V and VI). The results showed that the 112R carriers have significantly elevated cholesterol levels and have more abnormal cholesterol rates in both the control and AMD groups, regardless of analyzing the data as a continuous variable (Table V) or as a binary variable (≤200 mg/dl vs. > 200 mg/dl) (Table VI).

TABLE V.

Relationship Between Cholesterol Level (mg/dL) and ApoE112 Genotype

| AMD |

Control |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | |

| 112 CR + R/R | 29 | 200.8 ± 31.9 | 43 | 206.2 ± 32.9 | 72 | 203.5 ± 32.4 |

| 112 C/C | 91 | 192.7 ± 38.2 | 90 | 193.3 ± 35.0 | 181 | 193 ± 36.6a |

P < 0.01, t-test, in comparison of Cholesterol means between 112 CR+R/R and 112 C/C.

TABLE VI.

Abnormal Rates of Cholesterol (>200 mg/dl) in Individuals with Different ApoE112 SNP-types

| AMD |

Control |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal | Normal | All | Abnormal | Normal | All | Abnormal | Normal | All | |

| CR+R/R | 15 (51.7) | 14 | 29 | 25 (58.1) | 18 | 43 | 40 (55.6) | 32 | 72 |

| C/C | 33 (36.3) | 58 | 91 | 36 (40.0) | 54 | 90 | 69 (38.1) | 112 | 181 |

| X2/Pa | 2.19/0.14 | 4.05/0.04 | 6.75/0.01 | ||||||

Comparison of abnormal rates between CR+R/R and CC Carriers.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide further evidence that ApoE112R is associated with a reduced risk of AMD development. Although there are a few negative reports, this association has been previously reported. In the present study, a quantitative negative correlation between ApoE112R and AMD prevalence was observed with a lower OR for the PD AMD cases than for the CD AMD cases when comparing with the same control group. Furthermore, a higher OR was observed for the CD AMD group when compared with the BD control group than when compared with the screened controls. These results suggest a correlation between allele frequency and disease incidence.

In contrast to the protective role of ApoE E4 for AMD, the E4 isoform is associated with an increased risk for AD and various cardiovascular diseases [Mahley and Huang, 1999; Laws et al., 2003]. Current knowledge of the differential functioning among the ApoE isoforms, either in lipid metabolism or neuronal protection, does not readily provide a rationale for the observed protective role of E4 against AMD development [Nathan et al., 1994; Ji et al., 2002; Laws et al., 2003]. ApoE is expressed in photoreceptor outer-segments, the retinal ganglion layer, and both layers of Bruch's membrane. ApoE is also basally secreted by RPE cells [Anderson et al., 2001; Ishida et al., 2004]. It has been postulated that ApoE may facilitate lipid efflux from RPE cells and lipid transport across Bruch's membrane, thus reducing lipid deposit levels [Souied et al., 1998]. However, this hypothesis does not account for the fact that ApoE is a significant component of drusen [Anderson et al., 2001].

Altered ApoE function caused by the 112R variant may indeed play a role in AMD pathogenesis. Incubation with wild-type ApoE E3 or variant ApoE E4-enriched 3-VLDL results in differential cellular accumulation [Ji et al., 1998; Laws et al., 2003]. A two- to threefold increase in the accumulation of ApoE E3 over ApoE E4 has been observed in various cell types [Ji et al., 2002]. If mechanisms for proper clearance in the retina and Bruch's membrane are not in place, this accumulation may serve as a pathogenic basis for disease development [Ambati et al., 2003; Tuo et al., 2004b]. In fact, the increased accumulation in non-E4 carriers may explain why ApoE is such a ubiquitous component of ocular drusen in AMD-afflicted eyes [Crabb et al., 2002].

ApoE also may be involved in AMD pathogenesis through its association with C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. A chronic inflammation theory has been proposed to account for macular drusen etiology [Anderson et al., 2002]. CRP, a systemic inflammatory marker, is a prominent drusen-associated molecule and is expressed in significantly higher levels among advanced AMD patients [Seddon et al., 2004]. Persons with one or two copies of ApoE E4 are associated with reduced CRP levels when compared to individuals lacking these copies [Austin et al., 2004; Judson et al., 2004; Marz et al., 2004]. This finding suggests that an ApoE isoform-mediated inflammatory response may be involved in AMD etiology.

It has been reported that up-regulated macrophage and inflammatory cell function may worsen or exacerbate already existing inflammatory lesions [Espinosa-Heidmann et al., 2003]. This up-regulation can be spurred by both CCL2 and VEGF expression. Our functional study demonstrated a stronger suppression of both CCL2 and VEGF expression in RPE cells by the ApoE E4 isoform (Figs. 1 and 2). These findings implicate a possible mechanism underlying the observed protective effect of this allele. RPE cells constitutively express CCL2, a CC chemokine, and secrete VEGF, a growth factor and cytokine [Holtkamp et al., 1999; Crane et al., 2000]. Increased levels of both CCL2 and VEGF in RPE cells are related to oxidative stress and hypoxia within the eye [Spilsbury et al., 2000; Uetama et al., 2003]. VEGF is a potent endothelial cell mitogen and angiogenic growth factor strongly expressed in postmortem AMD eyes both with and without choroidal neovascularization [Lip et al., 2001]. Over-expression of VEGF in the RPE, even if only temporarily, is sufficient to induce choroidal neovascularization in the rat eye [Kliffen et al., 1997; Spilsbury et al., 2000]. CCL2 also has been associated with further deterioration and degeneration, especially in advanced disease stages [Ambati et al., 2003]. Considering that our data show nearly a twofold greater suppression of CCL2 mRNA and protein expression by E4 in RPE cells with similar findings for VEGF, we suggest that investigating the varied effects of the ApoE isoforms on chemokine and cytokine regulation may offer insights into the mechanisms responsible for the observed protective role of the E4 isoform.

As mentioned previously, the ApoE E4 isoform has been correlated with elevated total cholesterol levels [Smith, 2000; Ribalta et al., 2003]. This association remains true in this study (Tables V and VI). Although it is difficult to draw any mechanistic conclusions from this correlation, these results do support the validity and accuracy of our SNP typing methodology. These results also suggest a serum cholesterol-independent disease pathway in AMD [van Leeuwen et al., 2004].

Although difficulty was met in recruiting age-matched controls for an older AMD group, the likelihood of a false-positive was not increased. The incorporation of more closely age-matched controls would certainly increase the statistical power of this study. It is possible that some of the individuals in the BD control group will develop AMD later in life due to the age-related nature of the disease. Therefore, if the 112R polymorphism is a true protective factor against AMD, an even greater difference in the polymorphic frequencies between the case and control groups is anticipated if a more closely age-matched control population was included. This may explain why a lower OR was obtained for the CD AMD group when compared to the BD controls. With the lowest OR of 112R carriers in the PD AMD group, our results indicate that a clearly-defined phenotype also will increase the likelihood of successful genetic factor discrimination.

In conclusion, this study confirms that ApoE112R is associated with a deceased risk of AMD development. The underlying mechanisms of AMD development may involve altered regulation of CCL2 and VEGF expression in RPE cells by the ApoE isoforms. We are continuing to investigate the potential interaction among ApoE, other AMD-associated genes, and environmental factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Katherine Shimel, R.N. and Young Kim, R.N. for participant and patient recruitment. We would also like to thank Dr. Congxiao Zhang for assistance in culturing the human ARPE-19 cells used in the functional studies.

REFERENCES

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group Risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration. A case-control study in the age-related eye disease study: Age-related eye disease study report number 3. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2224–2232. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C, E, β-carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, Sakurai E, Lynn BC, Kuziel WA, Rollins BJ, Ambati BK. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Ozaki S, Nealon M, Neitz J, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. Local cellular sources of apolipoprotein E in the human retina and retinal pigmented epithelium: Implications for the process of drusen formation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:767–781. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00961-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MA, Zhang C, Humphries SE, Chandler WL, Talmud PJ, Edwards KL, Leonetti DL, McNeely MJ, Fujimoto WY. Heritability of C-reactive protein and association with apolipoprotein E genotypes in Japanese Americans. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:179–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird PN, Guida E, Chu DT, Vu HT, Guymer RH. The ε2 and ε4 alleles of the apolipoprotein gene are associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1311–1315. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes. The odds ratio. BMJ. 2000;320:1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J, Korczyn AD, Karussis DM, Michaelson DM. The effects of APOE genotype on age at onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurology. 2001;57:1482–1485. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb JW, Miyagi M, Gu X, Shadrach K, West KA, Sakaguchi H, Kamei M, Hasan A, Yan L, Rayborn ME, Salomon RG, Hollyfield JG. Drusen proteome analysis: An approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222551899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane IJ, Wallace CA, McKillop-Smith S, Forrester JV. Control of chemokine production at the blood-retina barrier. Immunology. 2000;101:426–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong PT, Bergen AA, Klaver CC, van Duijn CM, Assink JM. Age-related maculopathy: Its genetic basis. Eye. 2001;15:396–400. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentchev T, Milam AH, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Dunaief JL. Amyloid-β is found in drusen from some age-related macular degeneration retinas, but not in drusen from normal retinas. Mol Vis. 2003;9:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dithmar S, Curcio CA, Le NA, Brown S, Grossniklaus HE. Ultra-structural changes in Bruch's membrane of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AO, Ritter IR, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:421–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1110189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Suner IJ, Hernandez EP, Monroy D, Csaky KG, Cousins SW. Macrophage depletion diminishes lesion size and severity in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3586–3592. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DS, Katz J, Bressler NM, Rahmani B, Tielsch JM. Racial differences in the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration: The Baltimore eye survey. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Munoz B, Tomany SC, McCarty C, de Jong PT, Nemesure B, Mitchell P, Kempen Jon behalf of the Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:419–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1110359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp GM, De Vos AF, Peek R, Kijlsta A. Analysis of the secretion pattern of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and transforming growth factor-β2 (TGF-β2) by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain D, Ambati B, Adamis AP, Miller JW. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman L, Neborsky R. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: An update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:171–175. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida BY, Bailey KR, Duncan KG, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL, Kane JP, Schwartz DM. Regulated expression of apolipoprotein E by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:263–271. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300306-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik GP. Genetic predictors of common disease: Apolipoprotein E genotype as a paradigm. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji ZS, Pitas RE, Mahley RW. Differential cellular accumulation/retention of apolipoprotein E mediated by cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Apolipoproteins E3 and E2 greater than E4. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13452–13460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji ZS, Miranda RD, Newhouse YM, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y, Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid β peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21821–21828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson R, Brain C, Dain B, Windemuth A, Ruano G, Reed C. New and confirmatory evidence of an association between APOE genotype and baseline C-reactive protein in dyslipidemic individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver CC, Kliffen M, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Cruts M, Grobbee DE, Van Broeckhoven C, de Jong PT. Genetic association of apolipoprotein E with age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 1998a;63:200–206. doi: 10.1086/301901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver CC, Wolfs RC, Assink JJ, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Genetic risk of age-related maculopathy. Population-based familial aggregation study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998b;116:1646–1651. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.12.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver CC, Ott A, Hofman A, Assink JJ, Breteler MM, de Jong PT. Is age-related maculopathy associated with Alzheimer's Disease? The Rotterdam study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:963–968. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, Sangiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 2005;308:385–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1109557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliffen M, Sharma HS, Mooy CM, Kerkvliet S, de Jong PT. Increased expression of angiogenic growth factors in age-related maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:154–162. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliffen M, Lutgens E, Daemen MJ, de Muinck ED, Mooy CM, de Jong PT. The APO(*)E3-Leiden mouse as an animal model for basal laminar deposit. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1415–1419. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.12.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- la Cour M, Kiilgaard JF, Nissen MH. Age-related macular degeneration: Epidemiology and optimal treatment. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:101–133. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws SM, Hone E, Gandy S, Martins RN. Expanding the association between the APOE gene and the risk of Alzheimer's disease: Possible roles for APOE promoter polymorphisms and alterations in APOE transcription. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1215–1236. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip PL, Blann AD, Hope-Ross M, Gibson JM, Lip GY. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with increased vascular endothelial growth factor, hemorheology and endothelial dysfunction. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:705–710. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00663-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E: From atherosclerosis to Alzheimer's disease and beyond. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:207–217. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz W, Scharnagl H, Hoffmann MM, Boehm BO, Winkelmann BR. The apolipoprotein E polymorphism is associated with circulating C-reactive protein (the Ludwigshafen risk and cardiovascular health study) Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2109–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre LM, Martin ER, Simonsen KL, Kaplan NL. Circumventing multiple testing: A multilocus Monte Carlo approach to testing for association. Genet Epidemiol. 2000;19:18–29. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(200007)19:1<18::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SM, Greene T, Gutman FA. A twin study of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:757–766. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RF, Russell SR, Anderson DH, Hageman GS. Drusen associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease. FASEB J. 2000;14:835–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan BP, Bellosta S, Sanan DA, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Pitas RE. Differential effects of apolipoproteins E3 and E4 on neuronal growth in vitro. Science. 1994;264:850–852. doi: 10.1126/science.8171342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribalta J, Vallve JC, Girona J, Masana L. Apolipoprotein and apolipoprotein receptor genes, blood lipids and disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:177–187. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Saunders AM, De La Paz MA, Postel EA, Heinis RM, Agarwal A, Scott WK, Gilbert JR, McDowell JG, Bazyk A, Gass JD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Association of the apolipo-protein E gene with age-related macular degeneration: Possible effect modification by family history, age, and gender. Mol Vis. 2000;6:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz DW, Klein ML, Humpert A, Majewski J, Schain M, Weleber RG, Ott J, Acott TS. Lack of an association of apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms with familial age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:679–683. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Rosner B, Sperduto RD, Yannuzzi L, Haller JA, Blair NP, Willett W. Dietary fat and risk for advanced age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1191–1199. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Gensler G, Milton RC, Klein ML, Rifai N. Association between C-reactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 2004;291:704–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Cote J, Page WF, Aggen SH, Neale MC. The US twin study of age-related macular degeneration: Relative roles of genetic and environmental influences. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli F, Margaglione M, Testa F, Cappucci G, Manitto MP, Brancato R, Rinaldi E. Apolipoprotein E polymorphisms in age-related macular degeneration in an Italian population. Ophthalmic Res. 2001;33:325–328. doi: 10.1159/000055688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD. Apolipoprotein E4: An allele associated with many diseases. Ann Med. 2000;32:118–127. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souied EH, Benlian P, Amouyel P, Feingold J, Lagarde JP, Munnich A, Kaplan J, Coscas G, Soubrane G. The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene as a potential protective factor for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury K, Garrett KL, Shen WY, Constable IJ, Rakoczy PE. Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the retinal pigment epithelium leads to the development of choroidal neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:135–144. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64525-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo J, Bojanowski CM, Chan CC. Genetic factors of age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004a;23:229–249. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo J, Smith B, Bojanowski CM, Meleth AD, Gery I, Csaky K, Chew E, Chan CC. The involvement of sequence variation and expression of CX3CR1 in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J. 2004b;18:1297–1299. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1862fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo J, Ning B, Bojanowski CM, Lin Z, Ross RI, Reed GF, Shen D, Jiao X, Zhou M, Chew EY, Kadlubar FF, Chan CC. Synergic effect of polymorphisms in ERCC6 5′ flanking region and complement factor H on age-related macular degeneration predisposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603485103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetama T, Ohno-Matsui K, Nakahama K, Morita I, Mochizuki M. Phenotypic change regulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) gene expression in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197:77–85. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen R, Klaver CC, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Stricker BH, de Jong PT. Cholesterol and age-related macular degeneration: Is there a link? Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:750–752. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannis VI. Genetic polymorphism in human apolipoprotein E. Methods Enzymol. 1986;128:823–851. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)28109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareparsi S, Reddick AC, Branham KE, Moore KB, Jessup L, Thoms S, Smith-Wheelock M, Yashar BM, Swaroop A. Association of apolipoprotein E alleles with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration in a large cohort from a single center. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1306–1310. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]