Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is a re-activation infection associated with severely impaired T cell-mediated immunity. We describe a patient with long-standing Crohn's disease and thymoma who developed severe CMV retinitis. While thymoma can be associated with impaired humoral immunity and a quantitative CD4+ T helper cell deficiency, these were not evident in our patient. However, more detailed investigation of anti-CMV responses showed absence of specific T cell responses to CMV antigen. Normal CMV seropositive controls have detectable proliferation and interferon-γ production by T cells in response to stimulation with CMV antigen, but this was absent in this patient both during the acute infection and in convalescence. Other measures of T cell function were normal. Since CMV retinitis is due to reactivation of latent CMV infection, it appears that selective loss of CMV-specific immunity had occurred, perhaps secondary to a thymoma. The causes of thymoma-associated immune impairment are not understood, but this case demonstrates that selective defects can occur in the absence of global T cell impairment. Opportunistic infections should therefore be suspected in patients with thymoma even in the absence of quantitative immune deficiencies.

Keywords: thymoma, cytomegalovirus, retinitis, immunodeficiency

INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is a secondary reactivation of latent CMV infection that is a common and characteristic manifestation of the immunodeficiency associated with advanced HIV-1 infection. It is rarely described in patients with other defects of cell-mediated immunity. We describe the case of a male with longstanding inflammatory bowel disease who developed thymoma in late life. He subsequently suffered sight-threatening biopsy-proven CMV retinitis. Though T-cell numbers and standard mitogenic responses were normal, specific T-cell responses in vitro to CMV were demonstrably depressed.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old-retired engineer with a previous history of Crohn's disease and thymoma presented in February 1999 with reduced visual acuity. He had previously had bilateral extracapsular cataract extractions with intraocular lens implants in 1985 and 1987, and had a left retinal detachment repair and right cryotherapy in 1986. Deterioration in visual acuity was initially attributed to posterior capsular thickening although keratic precipitates and flare were noted bilaterally with cells in the aqueous and vitreous. Right visual acuity initially improved after 2 yag laser capsulotomies. There was extensive field loss in the left eye and loss of the lower half of the right visual field. Topical steroid therapy had little effect, and a course of oral steroids resulted in significant clinical deterioration in both eyes. In July 1999 a vitreous biopsy was obtained and was positive for CMV by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and CMV pp65 early antigen was detected in the blood. HIV serology was negative.

Thymoma had been diagnosed in 1997, when a chest X-ray revealed mediastinal widening and thoracic CT demonstrated a 13-cm anterior mediastinal mass associated with pre- and paratracheal nodes. Biopsy and subsequent thymectomy confirmed a benign spindle cell thymoma.

The diagnosis of extensive small bowel Crohn's disease was made in 1994 on clinical and radiological grounds, and he made an initially satisfactory response to Pentasa. Over the following year a trial of anti-ΤΝFα antibody infusions failed to control a flare of disease activity. Corticosteroids were commenced and azathioprine was commenced in late 1995. Steroids were discontinued completely after a Colles' fracture in 1996. In 1997 a further relapse of his Crohn's disease responded to oral Budesonide.

On admission visual acuity was found to be 6/60 bilaterally with gross field loss. He was commenced on a combination of ganciclovir and foscarnet. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia was instituted and azathioprine withdrawn. Slow subjective and fundoscopic improvement followed over the three week period of induction. Foscarnet was withdrawn but maintenance ganciclovir continued at home via a Hickman line and portable infusion device. Surgery for a right retinal detachment was required in December 1999 resulting in visual acuity of 6/60 with preservation of navigational vision.

METHODS

Controls

Healthy laboratory staff volunteers were used to obtain normal control data, grouped according to their CMV serological status.

Lymphocyte subset analysis

Peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets were analysed by whole-blood labelling with fluorescent conjugates of monoclonal antibodies against CD3 (UCHT1UK), CD4 (SFCl12T4D11), CD8 (SFCl21ThyD3), CD19 (J4·119), CD16 (3G8) and CD56 (N901/NKH-1), all from Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK. Cells were analysed after fixation and red cell lysis on an Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

T cell proliferation assays

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated by centrifugation on Histopaque (Sigma, Poole, UK). The cells were washed and resuspended at 106/ml in complete medium, and 100 μl aliquots were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 or 5 days with phytohaemagglutinin, pokeweed mitogen, OKT3, tetanus toxoid (Statens Institute, Denmark), crude candida antigen (kind gift of Dr D. Kumararatne, Birmingham, UK) or CMV antigen (Serion Immundiagnostica GmbH, Wurzburg, Germany). Proliferation was detected by measurement of 3H-thymidine incorporation (Amersham UK, Amersham, UK) for the last 16 h of culture.

Detection of T cell intracellular IFN-γ production

1 ml of heparinized whole blood was incubated at 37°C for 6 h with 1 μg/ml CMV antigen, staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), or in the absence of antigen. Brefeldin A was added after 2 h and EDTA was added to a final concentration of 2 mm at the completion of incubation. Red blood cells were lysed by adding 5 ml of distilled water, followed by 5 ml of 1·8% saline. The remaining cells were washed in complete medium, and finally fixed overnight in 0·5% formaldehyde in borate buffered saline at 4°C. Fixed stimulated cells were washed and resuspended in a 0·1% saponin buffer with 10% FCS and labelled with directly conjugated fluorescent antibodies against IFN-γ (clone 45·15, Immunotech, France), CD69 (clone TP1·55·3, Immunotech), CD4 and CD8. The labelled cells were analysed in 4 colours on an Epics XL flow cytometer.

RESULTS

Hypogammaglobulinaemia had been noted first in 1995, 2 years before the diagnosis of thymoma. Lymphocyte subset analysis in 1997 showed typical findings associated with thymoma, with an inverted CD4/CD8 ratio and absent B cells (Table 1). Absolute CD4+ T cell numbers remained within the normal range at all times. After thymectomy IgA and IgM levels remained reduced, but IgG levels showed signs of recovery, and specific IgG against tetanus toxoid and pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide were normal. Unusually for a patient with thymoma, the CD4/CD8 ratio reverted to normal, and polyclonal B cells also became detectable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Serum immunoglobulins (g/l) and peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets ( × 109/l) prior to and during diagnosis and treatment of thymoma and CMV retinitis. Thymoma was diagnosed in December 1997 and CMV retinitis confirmed in July 1999. Lymphocyte subset proportions in the vitreous humour in July 1999 are also given

| Sept 95 | Dec 97 | July 99 | July 00 | Normal | Vitreous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum immunoglobulins (g/l) | ||||||

| IgA | 0·61 | 0·68 | 0·52 | 0·40 | 0·7–3·9 | |

| IgG | 4·67 | 6·86 | 7·02 | 5·26 | 6·0–15 | |

| IgM | 0·26 | 0·31 | 0·24 | 0·19 | 0·4–2·7 | |

| Lymphocytes (×109/l) | 2·23 | 2·83 | 3·00 | 1·5–5·4 | ||

| CD3+ | 2·00 | 2·63 | 1·92 | 1·0–2·1 | 86·6% | |

| CD4+ | 0·85 | 1·78 | 1·11 | 0·5–1·7 | 38·4% | |

| CD8+ | 1·16 | 0·91 | 0·71 | 0·2–1·0 | 43·7% | |

| CD19+ | 0·00 | 0·00 | 0·90 | 0·04–0·40 | <1% | |

| CD3-,CD16/56+ | 0·02 | 0·03 | 0·10 | 0·06–0·24 | 7·7% | |

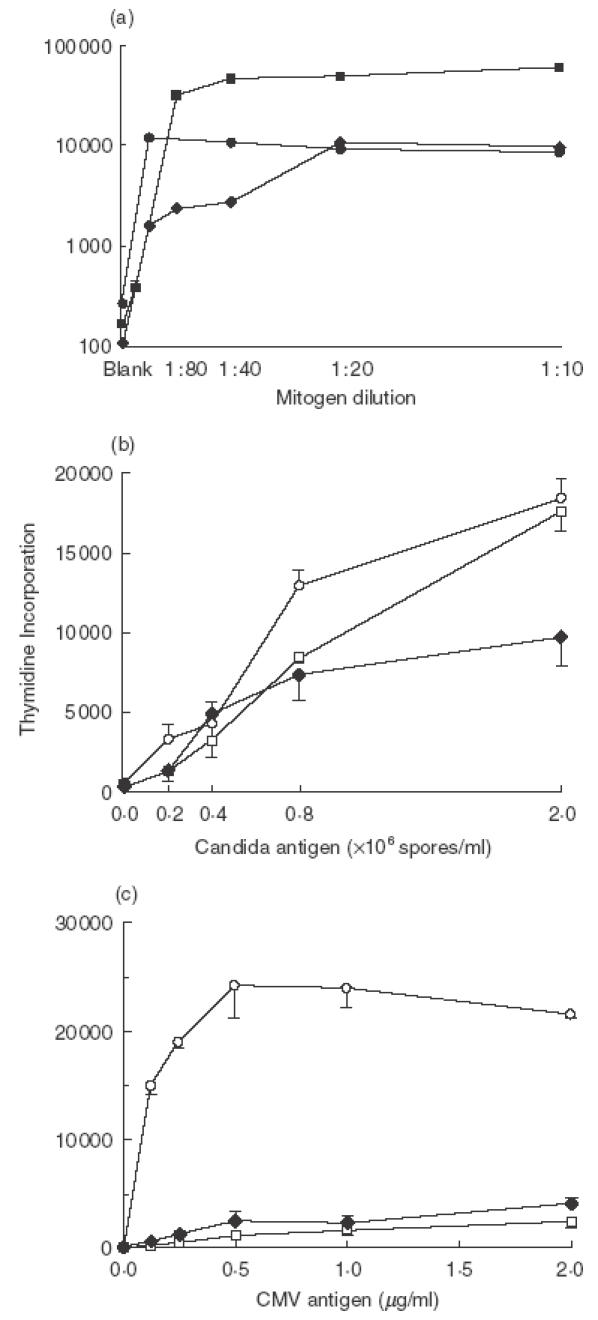

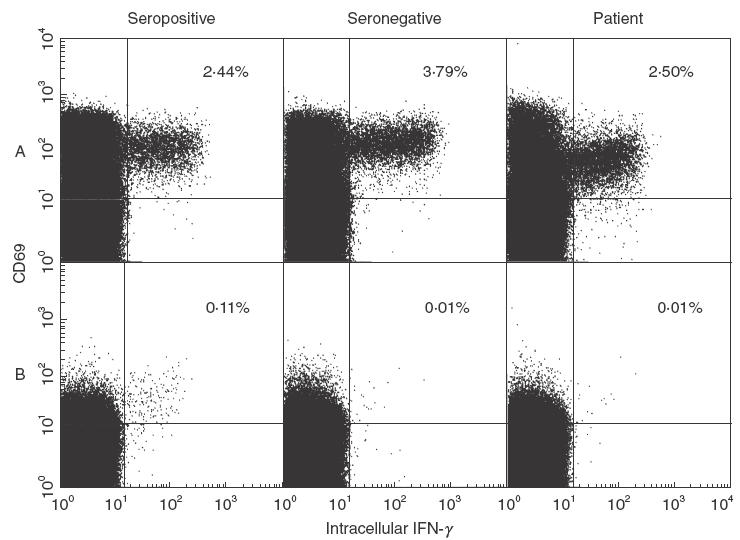

Specific IgG to CMV was detected both at diagnosis and in convalescence, supporting the view that the CMV retinitis represents a reactivation of previously latent infection. Such opportunistic infection with CMV is associated with defective cell-mediated immunity, typically a marked CD4 lymphopaenia [1]. In view of the normal CD4 count in this patient, we investigated his T cell function. Normal T cell proliferation was de-tected in response to mitogens (phytohaemagglutinin, pokeweed mitogen and OKT3; Fig. 1). Antigen-specific T cell proliferation to candida and SEB-induced IFN-γ production were normal in the patient and in CMV-seropositive and seronegative controls (Figs 1 and 2). However T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production in response to CMV antigen were undetectable in both the (seropositive) patient and a CMV-seronegative control (Figs 1 and 2). In normal control studies, T cell IFN-γ production was undetectable (less than or equal to 0·01%) in CMV seronegative individuals (n = 9), with a mean of 0·2% positive T cells (range 0·04–0·62%) in seropositive controls (n = 6). T cell proliferation responses to CMV were not restored by the addition of IL-12 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Proliferation of the patient's lymphocytes (filled symbols) in response to (a) mitogens, (b) candida antigen and (c) CMV antigen. Dilutions of each mitogen are indicated. ▪ PHA 250 μg/ml; • PWM 100 μg/ml; ♦ OKT3 1 μg/ml. Mean 3H thymidine incorporation (±SEM) is expressed as disintegrations per minute. T cell proliferative responses of a CMV seronegative control (□) and a CMV seropositive control (○) are also shown for Candida and CMV antigens. All of the patient's mitogen proliferation responses were equivalent to or greater than normal control responses (not shown).

Fig. 2.

IFN-γ production by T cells on incubation with (a) SEB or (b) CMV antigen. Both seropositive and seronegative normal donors and the patient show normal IFN-γ production on stimulation with SEB. IFN-γ production is also induced by stimulation with CMV antigen in a normal CMV seropositive donor, but not in a normal seronegative donor. The seropositive patient showed no induction of this cytokine. Figures are gated on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CD69 expression identifies activated T cells.

DISCUSSION

Cytomegalovirus retinitis is rarely described in patients uninfected with the human immunodeficiency virus: cases are occasionally reported in the context of severe immunosuppression such as bone marrow transplantation [2–4]. A single case was recently reported of its occurrence in association with thymoma in a patient with severe CD4 lymphopaenia and other opportunistic infections [5]. The cause of the defect in cell-mediated immunity in thymoma is uncertain, but patients usually have reduced T cell numbers, and often generalized defects in in vitro T cell proliferation in response to mitogens and antigens [5,6]. Our patient did not have a CD4 lymphopaenia at any time either prior to or during CMV infection, so that a qualitative defect in T cell function was suspected. However global measures of T cell function were normal, including proliferative responses to mitogenic and recall antigen stimulation and IFN-γ production in response to SEB. Nevertheless, specific defects in CMV-induced proliferation and IFN-γ production were detected. This suggests that the patient has specifically lost T cell responsiveness to CMV while remaining globally immunocompetent. We cannot be certain that T cell responses to all other antigens are normal, but he has not suffered any other infections to suggest otherwise. However, we can be confident that the defect in CMV-specific response is acquired, since CMV retinitis is a re-activation infection rather than a primary infection, and the patient's serology during the acute infection confirmed prior seroconversion due to primary infection.

CMV-specific T cell responses were detected by proliferation and cytokine expression assays using a whole CMV antigen preparation in order to maximize the repertoire of antigens available. No systematic study of responses to this CMV antigen preparation has been performed, but in a small series of 9 seropositive donors intracellular IFN-γ was induced in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in all donors in response to this stimulus [7]. Responses in seronegative donors in this series were also similar to those observed in our patient and seronegative donors. Our own control studies have shown that T cell IFN-γ production correlates very well with serological status in our assay; it is present in all seropositive donors and undetectable in seronegative donors. In addition, we performed proliferation assays that confirm the patient's broad nonreactivity to the virus.

The patient appears to have lost the capacity to suppress latent CMV infection. Control of latent CMV in the mouse has been shown to depend on specific T cell and natural killer (NK) cell function [8]. In these experiments, depletion of different T cell subsets, NK cells and IFN-γ demonstrated that a combination of deficiencies was required for maximum systemic reactivation of latent CMV. The combined depletion of CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ resulted in high levels of reactivation, surpassed only by the depletion of multiple lymphocyte subsets. The use of an IFN-γ receptor knockout mouse model also supported the central role of this cytokine in maintaining CMV latency [9]. Loss of control of latent infection in this patient may therefore be directly attributable to the inability of CD4+ T cells to produce IFN-γ in response to CMV. The proliferation and cytokine production assays that we used detect principally this CD4+ T helper cell activity, since antigen presentation to CD8 + cytotoxic T cells will be limited. We were unable to test CMV-specific cytotoxic responses in this patient. However, such responses are highly dependant on specific T helper responses, and the experimental data cited above suggest that cytotoxicity is likely to be markedly impaired in the absence of antigen-specific IFN-γ production.

Absence of NK cells has been suggested to be a cause of recurrent herpes virus infections in humans [10], although no further strong evidence for this association has been presented subsequently. Furthermore, Polic et al. [8] found no loss of control of latent murine CMV if only NK cells were depleted. Our patient had normal numbers of circulating NK cells and evidence of recruitment of these to the site of infection (Table 1). NK cell function was not specifically tested in this patient.

Loss of CMV-specific CD4 T cells is also observed in HIV patients with profoundly reduced CD4 counts (usually less than 0·1 × 109/l). However in these patients anti-CMV reactivity recovered on treatment with ganciclovir and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [11]. In contrast our patient showed no restoration of anti-CMV responses even after successful anti-CMV therapy. Our patient received no additional therapy to restore T cell function analogous to HAART in HIV patients, although certain immune indices such as CD4+ T cell and B cell numbers did improve after thymectomy.

We propose that the loss of CMV-specific immunity is related to the patient's thymoma, although this cannot be established beyond question. Opportunistic infections are described in thymoma, always in the context of other, often severe abnormalities of immune function [5]. A notable feature of this case is the apparent specificity of the defect for CMV immunity. This is not readily explained. Deletion or suppression of CMV-specific T cells might be implicated; it could be speculated for instance that abnormal expression of CMV antigen in the thymoma could result in such T cell regulatory abnormalities. Abnormalities of the T cell receptor repertoire have been described in thymoma patients [6], although the functional consequences of this are unknown. Impairment of immune function is found also in Crohn's disease. In common with other chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, global impairment of proliferative reponses to recall antigens and abnormalities of T cell subset distribution have been described [12]. In vitro defects of NK cell function have also been observed [13]. However, antigen-specific defects of immunity such as in our patient have not been described to our knowledge, and Crohn's disease patients do not succumb to opportunistic infections in the absence of severe therapeutic immunosuppression.

There may have been an ineffective immune response to the CMV infection, since the vitreous humour did show lymphocyte recruitment, with enrichment for CD8+ T cells and NK cells (CD3-, CD16/56 +) compared with peripheral blood (Table 1). However this appropriate cellular recruitment clearly failed to control viral replication. This may actually be to the patient's advantage, since it is recognized that reconstitution of immunity in HIV patients starting HAART can be associated with worsening of CMV retinitis [1].

This case shows that the immunodeficiency associated with thymoma may be extremely restricted, but nonetheless clinically important. Opportunistic infection should be suspected in these patients even when gross indices of immune function are completely normal. The cause of such a specific defect remains unknown. For our patient, it is clearly sensible to continue specific anti-CMV therapy for as long as a CMV-specific immune response is undetectable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Anne Douglas and Louise Pillsworth who performed the lymphocyte proliferation assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitcup SM. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2000;283:53–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papanicolaou GA, Meyers BR, Fuchs WS, Guillory SL, Mendelson MH, Sheiner P, Emre S, Miller C. Infectious ocular complications in orthotopic liver transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1172–7. doi: 10.1086/513655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishburne BC, Mitrani AA, Davis JL. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after cardiac transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:104–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto T, Okada M, Mori A, et al. Successful treatment of severe cytomegalovirus retinitis with foscarnet and intraocular injection of ganciclovir in a myelosuppressed unrelated bone marrow transplant patient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:801–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarr PE, Sneller MC, Mechanic LJ, Economides A, Eger CE, Strober W, Cunningham-Rundles C, Lucey DR. Infections in patients with immunodeficiency and thymoma (Good Syndrome) Medicine. 2001;80:123–33. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masci AM, Palmieri G, Perna F, Monatella L, Merkabaoui G, Sacerdoti G, Martignetti A, Racioppi L. Immunological findings in thymoma and thymoma–related syndromes. Ann Med. 1999;31(Suppl.2):86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asanuma H, Sharp M, Maecker HT, Maino VC, Arvin AM. Frequencies of memory T cells specific for varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus by intracellular detection of cytokine expression. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:859–66. doi: 10.1086/315347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polic B, Hengel H, Krmpotic A, Trgovcich J, Pavic I, Luccaronin P, Jonjic S, Koszinowski UH. Hierarchical and redundant lymphocyte subset control precludes cytomegalovirus replication during latent infection. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1047–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Presti RM, Pollock JL, Dal Canto AJ, O'Guin AK, Virgin HW., 4th Interferon gamma regulates acute and latent murine cytomegalovirus infection and chronic disease of the great vessels. J Exp Med. 1998;188:577–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biron CA, Bryon KS, Sullivan J. Severe herpersvirus infections in an adolescent without natural killer cells. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1731–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906293202605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komanduri KV, Viswanathan MH, Wieder ED, Schmidt DK, Bredt BM, Jacobson MA, McCune JM. Restoration of cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T-lymphocyte responses after ganciclovir and highly active antiretroviral therapy in individuals infected with HIV-1. Nat Med. 1998;4:953–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roman LI, Manzano L, De La Hera A, Abreu L, Rossi I, Alvarez-Mon M. Expanded CD4+CD45RO+ phenotype and defective proliferative response in T lymphocytes from patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1008–19. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giacomelli R, Passacantando A, Frieri G, et al. Circulating soluble factor-inhibiting natural killer (NK) activity of fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Clin Exp Imm. 1999;115:72–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]