Antibiotic treatment can usually help in symptomatic recovery in Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea (CDAD), but recurrent episodes of diarrhoea remain a major problem.1,2,3,4 Besides increasing the dose or extending the course of antibiotics, and using alternating or pulsed regimens, there are no effective alternatives to prevent relapses.5 Previously, we reported on anti‐Clostridium difficile whey protein concentrate (anti‐CD‐WPC) made from the milk of cows immunised against C difficile and its toxins. Anti‐CD‐WPC is prepared using standard techniques used in the milk industry, and contains a high concentration of sIgA directed against C difficile and its toxins. It neutralises the cytotoxicity of C difficile toxins in vitro and protects hamsters against otherwise lethal C difficile‐associated cecitis.6

The aim of this study was to assess the preliminary efficacy of anti‐CD‐WPC in aiding the prevention of relapses in patients with CDAD confirmed by positive faecal C difficile toxin assay and culture before enrolment.7,8 After completion of at least 10 days of antibiotic treatment, patients received anti‐CD‐WPC for 2 weeks, with a follow‐up period of 60 days. Patients provided written, informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were a history of milk intolerance, or inability to receive oral fluids. Patients received anti‐CD‐WPC 15 g/day, divided into 3 equal doses, for 14 days. Anti‐CD‐WPC was added to flat mineral water, stirred and taken in an empty stomach 1 h before each meal. Patients kept a diary to report stool frequency (stools/day) and consistency (scored as normal, semiformed or watery). A relapse of CDAD was declared if the patient reported looser stools compared with the day before (eg, change from normal to semiformed) and an increase in stool frequency for two consecutive days, or a single day with an increase of ⩾3 stools, or any day with passage of >6 stools/day.

Tolerability and safety were monitored by self‐report diaries, laboratory monitoring and active surveillance by interview, and has been reported elsewhere.9

We enrolled 101 patients (51 female; median age 74 years) with a total of 109 CDAD episodes (table 1). Most patients had underlying conditions that made them susceptible to acquiring CDAD (ie, older age cohort, antibiotic usage, surgery, stay in the intensive care unit, immunosuppressive medication).1,2,3,4 Eight patients did not complete anti‐CD‐WPC (1 died because of underlying disease, 4 stopped because of taste dislike, 1 relapsed and in 2 the attending doctor made a decision of no treatment). Of those who completed the course, five patients died within the 60‐day follow‐up because of underlying disease. Seven received anti‐CD‐WPC twice and one received it thrice.

Table 1 Characteristics of 101 patients with Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea (CDAD; 109 episodes), who had or did not have relapse of CDAD after 2 weeks of the immune whey anti‐C difficile whey protein concentrate given after standard antibiotic treatment with oral metronidazole or vancomycin.

| Characteristic | Relapse | No relapse | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n) | >0.30 | ||

| Male | 5 | 49 | |

| Female | 6 | 49 | |

| Age (median and IQR; years)* | 76 (9) | 70 (27) | >0.20 |

| Chronic Health Scoring System† | <0.01 | ||

| Score 0 | 1 | 46 | |

| Score 2 | 0 | 8 | |

| Score 5 | 10 | 44 | |

| Episode of CDAD | >0.20 | ||

| First | 6 | 59 | |

| Second | 4 | 23 | |

| ⩾Third | 1 | 16 | |

| C difficile PCR‐ribotype O27 | >0.20 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 20 | |

| No | 7 | 75 | |

| Not determined | 0 | 3 | |

| Antibiotic treatment of last episode | >0.30 | ||

| Vancomycin | 8 | 50 | |

| Metronidazole | 3 | 45 | |

| In combination | 0 | 3 |

CDAD, Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea.

*IQR, interquartile range.

†Chronic Health Score in Acute Physiology, Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) prognostic scoring system: angina pectoris New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III–IV (n = 21); biopsy‐proven cirrhosis and documented portal hypertension (n = 9); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease resulting in exercise restriction (n = 28); renal insufficiency necessitating (chronic) dialysis (n = 6); and immunocompromised status—for example, high‐dose steroids, chemotherapy or an underlying haematological disease like chronic lymphatic leukaemia (n = 31), according to Knaus.10

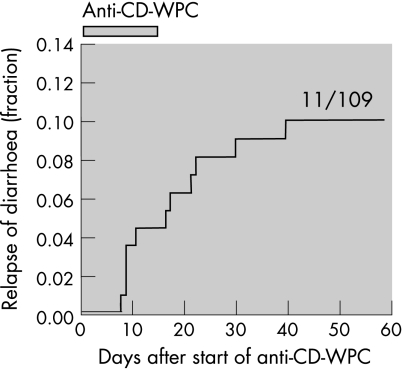

In all, 11 (∼10%) of 109 episodes were followed by a relapse of CDAD (table 1, fig 1). Faecal toxin assay and C difficile culture were positive in all cases. Patients with severe underlying disease were more likely (relative risk (RR) 11.7; 95% CI 1.5 to 96) to relapse than those without underlying condition, as were patients with C difficile PCR‐ribotype 027 (RR 2.2, 95% CI 0.6 to 8.2).

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier plot showing the fraction of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea (CDAD) episodes resulting in a relapse of CDAD during and after receiving anti‐C difficile whey protein concentrate (anti‐CD‐WPC). The immune whey preparation anti‐CD‐WPC was taken for 2 weeks (indicated in graph), after completion of at least 10 days of standard antibiotic therapy.

The findings indicate that anti‐CD‐WPC, an immune whey protein concentrate directed against C difficile and its toxins, may aid the prevention of relapse in CDAD. This is based on the 10% relapse rate in those given anti‐CD‐WPC, compared with a 20–25% relapse rate in contemporary controls in the Dutch epidemic and published relapse rates from 20% to 47% in C difficile type O27 epidemics.3,4,5 The effect of anti‐CD‐WPC is probably mediated by sIgA antibodies, and this has important advantages over repeated use of antibiotics, because of its suppression of resident microbial bowel flora and potential for inducing antibiotic resistance. In some relapsing subjects, the amount of anti‐CD‐WPC appeared insufficient to neutralise the C difficile toxins in the faeces, and there may be room for improvement by raising the dose. The findings merit clinical development of anti‐CD‐WPC, and should be confirmed in a prospective placebo‐controlled randomised trial.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded on a per‐patient basis by MucoVax bv., Leiden, The Netherlands.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Wilcox M H, Spencer R C. Clostridium difficile infection: responses, relapses and re‐infections. J Hosp Infect 19922285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett J G. Antibiotic‐associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002346334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary M E.et al Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ 2004171466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuijper E J, Coignard B, Tull P. The ESCMID Study Group for Clostridium difficile (ESGCD). Emergence of Clostridium difficile‐associated disease in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 200612(Suppl 6)2–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFarland L V. Alternative treatments for Clostridium difficile disease: what really works? J Med Microbiol 200554101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Dissel J T, de Groot N, Hensgens C M H.et al Bovine antibody‐enriched whey to aid in the prevention of a relapse of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea: preclinical and preliminary clinical data. J Med Microbiol 200554197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van den Berg R J, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet L S, Gerritsen H J.et al Prospective multicenter evaluation of a new immunoassay and real‐time PCR for rapid diagnosis of Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2005435338–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delmee M. Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 20017411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young K W H, Munro I C, Taylor S L.et al The safety of whey protein concentrate derived from the milk of cows immunized against. Clostridium difficile Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 200747317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knaus W A, Wagner D P, Draper E A.et al The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest 19911001619–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]