Abstract

Context

Only limited information exists about the epidemiology of DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder.

Objective

To present nationally representative data on the epidemiology of panic attacks and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia based on the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).

Design and Setting

Nationally representative face-to-face household survey conducted using the fully structured WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI).

Participants

9282 English-speaking respondents ages 18 and older.

Main Outcome Measures

DSM-IV panic attacks (PA) and panic disorder (PD) with and without agoraphobia (AG).

Results

Lifetime prevalence estimates are 22.7% for isolated panic without agoraphobia (PA-only), 0.8% for PA with agoraphobia without PD (PA-AG), 3.7% for PD without AG (PD-only), and 1.1% for PD with AG (PD-AG). Persistence, number of lifetime attacks, and number of years with attacks all increase monotonically across these four subgroups. All four subgroups are significantly comorbid with other lifetime DSM-IV disorders, with the highest odds for PD-AG and the lowest for PA-only. Scores on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale are also highest for PD-AG (86.3% moderate-severe) and lowest for PA-only (6.7% moderate-severe). Agoraphobia is associated with substantial severity, impairment, and comorbidity. Lifetime treatment is high (from 96.1% PD-AG to 61.1% PA-only), but 12-month treatment meeting published treatment guidelines is low (from 54.9% PD-AG to 18.2% PA-only).

Conclusions

Although the major societal burden of panic is due to PD and PA-AGG, isolated panic attacks also have high prevalence and meaningful role impairment.

Keywords: agoraphobia, panic attacks, panic disorder, epidemiology

Epidemiological surveys have helped advance understanding of panic by studying the prevalence and distribution,1–3 onset and course,4 associations with comorbid disorders,5–7 and societal costs.8, 9 Despite these advances, though, important questions remain unanswered about the epidemiology of panic,10 among the most important of them regarding the finding that many people experience isolated panic attacks that do not meet criteria for panic disorder. These people have elevated prevalence of other mental disorders.6, 11 They report higher impairment, use of psychotropic medication, and psychiatric help-seeking than people with many Axis I disorders.8 Such findings have led to the view that panic attacks are fairly nonspecific risk markers for psychopathology.12

Importantly, some people with isolated panic attacks meet criteria for agoraphobia.13 It is not known, though, whether the persistent course and poor outcome associated with agoraphobia among people with panic disorder14 also apply to panic attacks with agoraphobia. As a result, the boundary between panic attack and panic disorder and the relative role of agoraphobia within each are not well understood. Investigation and comparison of these symptom presentations in community samples might help clarify these issues. The current report presents initial data of this sort from the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).

METHODS

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative survey of 9282 English-speaking household residents ages 18+ in the coterminous United States. Face-to-face interviews were carried out between February 2001 and April 2003. The response rate was 70.9%. Consent was verbal rather than written to parallel the baseline NCS procedures. The Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan both approved the NCS-R recruitment and consent procedures. Respondents were interviewed in two parts. The Part I interview, administered to all respondents, included the core diagnostic assessment. The Part II interview, administered to all Part I respondents who met criteria for any lifetime core disorder plus a probability sub-sample of others (for a total of 5692 Part II respondents), assessed correlates and disorders of secondary interest. The Part I sample is used here to examine prevalence and course, clinical severity and role impairment, and most aspects of comorbidity. The Part II sample is used to examine comorbidity with disorders of secondary interest to the survey, socio-demographic correlates, and treatment. The Part I sample was weighted to adjust for differential probability of selection and discrepancies between the sample and the US population on Census socio-demographic and geographic variables. The Part II sample was additionally weighted to adjust for differential probability of selection from the Part I sample. More details on NCS-R sampling and weights are reported elsewhere .15

Panic and agoraphobia

Panic and agoraphobia were assessed using Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),16 a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview (www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi). The assessment of panic was comparable to that in previous version of the CIDI with the exception that a distinction was made between uncued panic attacks (described as occurring “out of the blue” with no triggering event) and cued panic attacks. A series of parallel questions was asked about each of these two types of attacks. Panic disorder was defined as the occurrence of four or more uncued panic attacks not due to substance use or a general medical condition accompanied by one month or more of either persistent concern about recurrence, worry about the implications of the attacks, or significant change in behavior because of the attacks. Agoraphobia was defined as anxiety about two or more situations that had to include “either being in crowds, going to public places, traveling by yourself, or traveling away from home” associated with a fear of having a panic attack and fear that it might be difficult or embarrassing to escape. This fear had to result either in avoidance of the feared situations, distress upon exposure to these situations, or the necessity of a companion during these situations. We used these classifications to define four subgroups for comparative analysis: panic attack without panic disorder and without agoraphobia (PA-only), panic attack with panic disorder, but with agoraphobia (PA-AG), panic disorder without agoraphobia (PD-only), and panic disorder with agoraphobia (PD-AG). PA-only is not a codable DSM-IV disorder. PA-AG is a subset of the DSM-IV category “agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder,” excluding respondents with agoraphobia who never had a panic attack. This latter subgroup is not considered in this report, as we focus exclusively on people with a history of panic.

As detailed elsewhere,17, 18 blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the lifetime non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)19 were administered to a probability sub-sample of 325 NCS-R respondents to assess concordance with CIDI diagnoses. CIDI-SCID concordance for PD diagnosis had an area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC) of .72, a moderate Kappa (standard error) of .45 (.15), and a very high odds-ratio (95% Confidence Interval) of 56.3 (15.5–204.6). No bias in the CIDI prevalence estimate compared to the SCID was found using a McNemar test (χ21 = 0.0, p = .820). CIDI-SCID concordance was not assessed for PA because the latter was not evaluated separately in the SCID, or for AG because it occurred too infrequently in the clinical reappraisal study for reliable analysis of concordance. DSM-IV requires “recurrent” uncued panic attacks, which could be interpreted as two or more, for a PD diagnosis. However, CIDI respondents who reported 2–3 lifetime uncued panic attacks generally were found in the SCID to have had only one full panic attack with additional limited symptom attacks. Validity of the CIDI in relation to the SCID consequently was improved when we required at least four lifetime uncued attacks in the CIDI. The insignificant McNemar test documents that the CIDI PD prevalence estimate does not differ significantly from the SCID estimate despite the SCID requiring only two attacks.

Course, severity, and impairment

Respondents who met DSM-IV lifetime criteria for PA were asked to estimate the age of onset (AOO) of their first attack and AOO of having four uncued attacks with a month of persistent worry. They were also asked to estimate their age at their most recent attack, number of lifetime uncued and cued attacks, and number of years with at least one attack. Clinical severity was assessed only for 12-month cases using a fully structured version of the seven-question Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) that was developed specifically for the NCS-R. (Question wording is posted at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs.) The clinician-administered version of the PDSS has been found to yield a reliable and valid assessment of overall panic disorder clinical severity.20 A separate fully structured version of the PDSS, developed independently of the NCS-R version but with very similar wording, has excellent concordance with the clinician-administered version.21 Published PDSS cut points were used to define severity (none, mild, moderate, severe).

Although two of the seven PDSS questions assess role impairment, a more generic measure of role impairment, the Sheehan Disability Scales (SDS),22 was also included in each section of the CIDI. The SDS asked respondents with 12-month panic to focus on the one month in the past year when their panic, their worry about having another panic attack, or their restriction of activity because of this worry interfered most with their life and activities, and to rate this interference on a 0-to-10 visual analogue scale with response options of none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), and very severe (10). Interference ratings were obtained for four role domains: home management, work, social life, and personal relationships. Responses were combined by taking the highest score across the four ratings and collapsing the severe and very severe response categories.

Comorbid DSM-IV disorders

The NCS-R assessed a number of other DSM-IV disorders: other anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and adult manifestations of separation anxiety disorder), mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, and bipolar I and II disorders), substance use disorders (alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence, where abuse and dependence on specific illicit drugs were combined with polysubstance abuse and dependence), and impulse-control disorders (intermittent explosive disorder and adult manifestations of three child-adolescent impulse-control disorders -- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, and conduct disorder). Organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making all diagnoses. As reported in more detail elsewhere,18 blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)19 found generally good concordance between CIDI and SCID diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders, with area under the ROC curve in the range .65–.81, Kappa in the range .33–.70, and odds-ratios in the range 6.3–877.0. Diagnoses of impulse-control disorders were not validated because the SCID does not assess these disorders.

Treatment

Two questions about lifetime and 12-month treatment of panic were asked at the end of the panic section. Part II respondents were additionally administered more general questions about whether they ever received treatment for any “problems with your emotions or nerves or your use of alcohol or drugs" and, if so, about types of professionals seen.23 Treatment was distinguished in five sectors: psychiatry, non-psychiatry mental health specialty, general medical, human services, and complementary-alternative (CAM). Questions about treatment in the 12 months before interview asked about number and duration of visits, number and duration of psychotherapy sessions, and name, dose, and duration of each medication used. No information was obtained about the content of psychotherapy. A rough measure of 12-month guideline-concordant treatment of panic was developed using these reports based on available evidence-based guidelines.24 Guideline-concordant treatment was defined as receiving either pharmacotherapy (at least two months of an appropriate medication, defined as antidepressants or anxiolytics,25 plus at least four visits to any type of medical doctor) or psychotherapy (at least eight visits with any health care or human services professional lasting an average of at least 30 minutes). The decision to require at least four physician visits for pharmacotherapy was based on the recommendation of at least four visits for medication evaluation, initiation, and monitoring during the acute and continuation phases of panic disorder medication treatment.24 The decision to require at least eight psychotherapy sessions was based on the fact that clinical trials demonstrating efficacy have generally included at least eight psychotherapy visits.24 As respondents who only began a course of treatment shortly before the interview could not fulfill the requirements, we counted respondents with at least two visits to an appropriate treatment sector if they were in treatment at the time of interview.

Analysis methods

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate prevalence and patterns of treatment. The actuarial method26 was used to estimate AOO distributions. Mean comparisons were used to examine illness course and severity-impairment. Logistic regression analysis27 was used to estimate associations with socio-demographic variables and comorbid DSM-IV disorders. Because the NCS-R sample design featured weighting and clustering, all analyses used the Taylor series design-based method,28 implemented in the SUDAAN software system.29 Significance tests of sets of coefficients in the logistic regression equations were made using Wald χ2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided design-based .05-level tests.

RESULTS

Prevalence

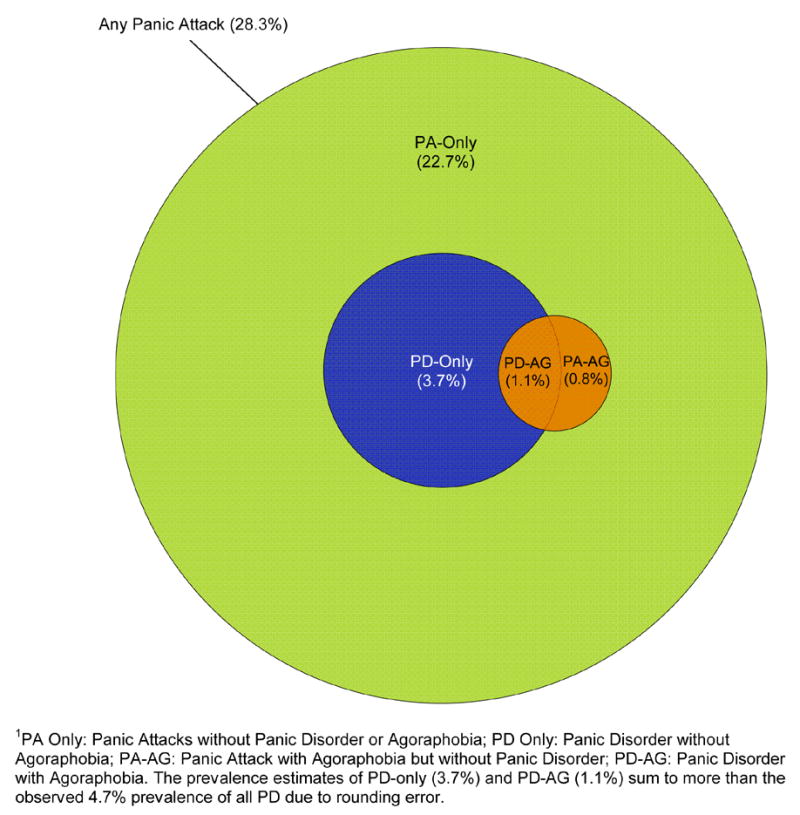

Twenty-eight percent [28.3% (1.0)] of respondents (standard error in parentheses) met criteria for lifetime panic attack and 11.2% (0.5) for 12-month PA, while 4.7% (0.3) of respondents (roughly one-sixth of those with lifetime PA) met criteria for lifetime panic disorder and 2.8% (0.2) for 12-month PD. Eight-tenths of one percent [ 0.8% (0.1)] of all respondents (roughly 3% of those with a lifetime PA) met criteria for lifetime PA with agoraphobia and 0.4% (0.1) for 12-month PA with AG, while 1.1% (0.1) of respondents (approximately one-fifth of those with lifetime PD and 60% of those with lifetime PA with AG) met criteria for lifetime PD with AG and 0.4% (0.1) for 12-month PD and AG.

Course of illness

As described above, respondents with lifetime PA were divided into four mutually exclusive subgroups (Figure 1): PA without PD and without AG (PA-only; 22.7% of the sample), PA without PD but with AG (PA-AG; 0.8%), PD without AG (PD-only; 3.7%), and PD with AG (PD-AG; 1.1%). A small proportion of respondents without PD (12.0% PA-only and 10.7% PA-AG) reported a sufficient number of uncued attacks to quality for PD (with means of 31.0 and 131.4 lifetime uncued attacks), but failed to meet other requirements for a PD diagnosis. (Table 1) The majority of respondents in three of the four subgroups, the exception being PD-only, reported at least one cued lifetime attack (from a low of 67.9% PD-AG to a high of 87.6% PA-AG). A significantly lower 46.8% of PD-only cases reported having any cued lifetime attack. Mean number of cued attacks among those with any varies significantly across subgroups (F3,1568 = 18.2, p < .001). PD is associated with a significantly higher mean number of cued attacks than PA both among those without AG (121.8 vs. 38.3, z = 6.6, p < .001) and those with AG (134.4 vs. 78.2, z = 2.1, p = .031). AG is associated with a significantly higher mean number of cued attacks among those with PA (78.2 vs. 38.3, z = 2.4, p = .016) but not among those with PD (134.4 vs. 121.8, z = 0.53, p = .60). In the sub-sample of respondents who reported ever having a cued attack, the mean number of such attacks substantially exceeds the mean number of uncued attacks both in the PD-only subgroup (121.8 vs. 31.3, z = 7.4, p < .001) and in the PD-AG subgroup (134.4 vs. 46.0, z = 4.0, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Lifetime prevalence estimates of DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder with and without agoraphobia1

Table 1.

Prevalence, persistence, and course of panic among respondents in four mutually exclusive lifetime panic subgroups

| PA-only1 | PA-AG1 | PD-only1 | PD-AG1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ23 | |

| I. Lifetime prevalence and persistence | |||||||||

| Prevalence | 22.7 | (1.0) | 0.8 | (0.1) | 3.7 | (0.2) | 1.1 | (0.1) | -- |

| 1 or more lifetime cued attacks | 76.2 | (1.2) | 87.6 | (4.4) | 46.8 | (3.0) | 67.9 | (5.5) | 90.7* |

| 4 or more lifetime uncued attacks | 12.0 | (1.1) | 10.7 | (4.1) | 100.0 | (0.0) | 100.0 | (0.0) | 0.1* |

| Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | F3,9278 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Panic attack AOO3 | 22.7 | (0.5) | 22.1 | (1.7) | 22.7 | (0.8) | 21.5 | (1.0) | 0.9 |

| Panic disorder onset | -- | -- | -- | -- | 23.6 | (0.9) | 22.9 | (1.0) | 0.5 |

| Agoraphobia onset | -- | -- | 19.3 | (1.8) | -- | -- | 17.0 | (1.4) | 0.9 |

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ23 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| II. Course of illness | |||||||||

| Twelve month persistence | 35.7 | (1.5) | 41.1 | (5.5) | 57.4 | (3.7) | 62.6 | (4.4) | 48.7* |

| Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | F3,9278 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Years with attacks | 4.7 | (0.2) | 6.6 | (1.1) | 8.3 | (0.6) | 10.7 | (1.1) | 20.4* |

| 1 or more lifetime cued attacks | 38.3 | (4.5) | 78.2 | (16.0) | 121.8 | (11.9) | 134.4 | (20.7) | 18.2* |

| 4 or more lifetime uncued attacks | 31.0 | (4.5) | 131.4 | (29.4) | 31.3 | (2.7) | 46.0 | (7.8) | 4.3* |

| Median 1 or more lifetime cued attacks | 6.0 | (0.3) | 9.2 | (2.2) | 17.2 | (8.8) | 34.1 | (70.4) | -- |

| Median 4 or more lifetime uncued attacks | 11.5 | (0.9) | 100.2 | (48.3) | 10.0 | (0.7) | 16.6 | (3.5) | -- |

| (n) | (1672) | (71) | (344) | (105) | |||||

PA-only = lifetime history of panic attack but not panic disorder or agoraphobia; PA-AG = lifetime history of panic attack with agoraphobia but not panic disorder; PD-only = lifetime history of panic disorder without agoraphobia

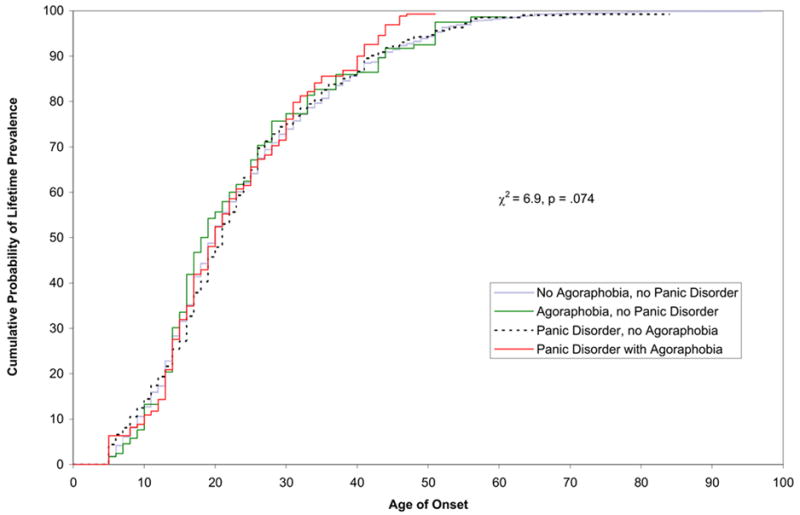

No meaningful difference exists in mean AOO of PA among the four subgroups (21.5–22.7; F3,2188 = 0.9, p = .44). Indeed, the entire PA AOO distribution is very similar across these subgroups. (Figure 2) Mean AOO of PD is only about one year later than mean AOO of PA and does not differ significantly between the PD-only and PD-AG subgroups (23.6 vs. 22.9, F3,1568 = 0.5, p = .62). Persistence (12-month prevalence of PA among lifetime cases), however, varies substantially, from a low of 35.7% in PA-only to a high of 62.6% in PD-AG (χ23 = 48.7, p < .001). Persistence is significantly higher in the PD than PA subgroups both in the absence of AG (57.4% vs. 35.7%, z = 5.4, p < .001) and the presence of AG (62.6% vs. 41.1%, z = 3.0, p = .002), but does not vary as a function of AG either in the two PA subgroups (41.1% vs. 35.7%, z = 0.9, p = .34) or in the two PD subgroups (62.6% vs. 57.4%, z = 0.9, p = .36). Mean number of years with attacks also varies significantly across the subgroups (F3,2188 = 46.7, p < .001) with the same rank ordering as persistence.

Figure 2.

Age of onset of first lifetime panic attack in four mutually exclusive lifetime panic subgroups

Socio-demographic correlates

We failed to find consistent variation in magnitude of significant socio-demographic correlates of lifetime prevalence across the four subgroups, although the odds-ratios (OR’s) associated with being female are noticeably higher for the PD than the PA subgroups, while the OR’s associated with “other” employment status are noticeably higher for the AG than non-AG subgroups. (Table 2) Age 60+ (versus younger ages) and Non-Hispanic Blacks (versus Non-Hispanic Whites) have reduced odds of panic in all four subgroups, although not all are significant. Women and previously married people have consistently elevated odds of panic in all four subgroups. Respondents classified as having “other” employment status, made up largely of the unemployed and disabled, have elevated odds of all outcomes other than PA-only, while retired people have elevated odds of PD-AG but not the other three outcomes. None of these associations is strong in substantive terms, though, with Pearson Contingency Coefficients for the set of socio-demographic predictors in the range .01–.02 in the four multivariate prediction equations.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic correlates of four mutually exclusive lifetime panic subgroups1

| PA-only2 | PA-AG2 | PD-only2 | PD-AG2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| 30–44 | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 1.6 | (0.6–4.4) | 1.5* | (1.1–2.1) | 1.7 | (1.0–2.8) |

| 45–59 | 0.9 | (0.7–1.2) | 1.7 | (0.5–6.0) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.4) |

| 60+ | 0.4* | (0.2–0.6) | 0.5 | (0.1–3.7) | 0.4* | (0.2–0.7) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) |

| χ2 | 29.2* | 4.0 | 24.2* | 35.5* | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Female | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.3) | 2.3* | (1.8–3.0) | 2.0* | (1.3–3.2) |

| χ2 | 16.5* | 1.2 | 38.6* | 9.1* | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.6* | (0.4–0.8) | 1.0 | (0.3–3.2) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.1) |

| Black | 0.7* | (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.5) | 0.4* | (0.3–0.6) | 0.5* | (0.2–1.0) |

| Other | 1.0 | (0.6–1.5) | 2.1 | (0.6–7.0) | 1.1 | (0.6–2.0) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.9) |

| White | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| χ2 | 27.7* | 2.5 | 23.5* | 5.1 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| 0–11 years | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| 12 years | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.1) |

| 13–15 years | 0.9 | (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.9) | 0.8 | (0.3–1.9) |

| 16+ years | 0.9 | (0.7–1.2) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.2) | 0.7 | (0.3–2.1) |

| χ2 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 10.3* | 0.7 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Sep./Widowed/Divorced | 1.1 | (0.8–1.4) | 2.2* | (1.1–4.2) | 1.6* | (1.2–2.1) | 1.3 | (0.7–2.3) |

| Never Married | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 1.2 | (0.5–3.2) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) |

| χ2 | 0.5 | 6.3* | 10.3* | 1.2 | ||||

| Employment Status | ||||||||

| Working | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Student | 0.8 | (0.5–1.4) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.5) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.4) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.9) |

| Homemaker | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) | 2.0 | (0.8–5.1) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.5–3.7) |

| Retired | 1.0 | (0.6–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.2–6.6) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.9) | 4.3* | (1.6–11.3) |

| Other | 1.1 | (0.9–1.5) | 3.6* | (1.8–7.1) | 1.5* | (1.0–2.2) | 3.8* | (2.1–6.8) |

| χ2 | 1.7 | 18.4* | 15.1* | 30.9* | ||||

| Family Income | ||||||||

| Low | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.3) | 1.3 | (0.9–2.0) | 1.4 | (0.6–3.2) |

| Low-Average | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.0) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.1) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.7) |

| High-Average | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) |

| High | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| χ2 | 8.4* | 0.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 | ||||

| (n)3 | (5172) | (3572) | (3844) | (3604) | ||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Based on multivariate logistic regression analyses that separately compare respondents in each of the four panic subgroups with respondents who have no lifetime history of panic.

PA-only = lifetime history of panic attack but not panic disorder or agoraphobia; PA-AG = lifetime history of panic attack with agoraphobia but not panic disorder; PD-only = lifetime history of panic disorder without agoraphobia; PD-AG = lifetime history of panic disorder with agoraphobia.

The sample sizes differ because respondents in each of the four mutually exclusive panic subgroups (1672 PA-only, 72 PA-AG, 344 PD-only, and 104 PD-AG) are compared separately with the 3500 respondents who have no history of panic.

Comorbidity

Respondents in all four panic subgroups have significantly elevated odds of virtually all other lifetime DSM-IV disorders assessed in the survey. (Table 3) One or more comorbid conditions are found in 71.9% of PA-only, 83.1% of PD-only, and 100% of the other two subgroups. The OR’s for particular comorbid conditions differ significantly across the four subgroups, with the lowest OR’s consistently in PA-only. In the case of comorbidity with other anxiety disorders and major depression, AG is more important than PD, as shown by the PA-AG OR’s (4.4–24.0) consistently being higher than the PD-only OR’s (2.0–5.4) and often as high as the PD-AG OR’s (2.5–25.8). In the case of the other mood disorders and alcohol use disorders, the PA-AG OR’s (3.2–5.0) are comparable to the PD-only OR’s (3.5–5.4), while the PD-AG OR’s (5.6–13.6) are considerably larger. A distinct pattern for drug use disorders is for the OR’s associated with all three AG or PD subgroups to be comparable in magnitude (3.4–5.8).

Table 3.

Comorbidities of four mutually exclusive lifetime panic subgroups with other DSM-IV disorders1

| PA-only2 | PA-AG2 | PD-only2 | PD-AG2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | χ23 | |

| I. Other anxiety disorders | |||||||||||||

| GAD | 10.0 | 2.4* | (1.7–3.2) | 31.9 | 8.5* | (4.9–14.6) | 21.3 | 4.4* | (2.9–6.8) | 15.0 | 2.6* | (1.4–4.8) | 33.6* |

| Specific phobia | 21.0 | 2.4* | (2.0–3.0) | 73.7 | 24.0* | (13.8–41.4) | 34.3 | 3.8* | (2.7–5.3) | 75.2 | 25.8* | (14.3–46.6) | 153.8* |

| Social phobia | 18.8 | 1.9* | (1.6–2.4) | 65.5 | 16.6* | (7.7–35.8) | 31.1 | 3.1* | (2.3–4.2) | 66.5 | 15.5* | (9.3–25.8) | 82.4* |

| PTSD | 12.0 | 3.0* | (2.3–3.9) | 24.2 | 5.8* | (2.3–14.6) | 21.6 | 5.0* | (3.4–7.5) | 39.6 | 11.6* | (6.8–19.7) | 40.7* |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2.1 | 1.5 | (0.5–4.3) | 0.0 | 3 | 3 | 8.2 | 5.4* | (1.8–16.1) | 19.6 | 20.2* | (5.5–73.9) | 20.8* |

| SAD | 7.7 | 3.1* | (2.3–4.0) | 13.8 | 6.3* | (2.7–14.5) | 11.0 | 4.4* | (2.6–7.5) | 23.5 | 11.6* | (7.1–19.0) | 40.6* |

| Any other anxiety disorder | 45.0 | 3.2* | (2.7–3.8) | 94.9 | 77.9* | (24.9–244.1) | 66.0 | 7.2* | (5.5–9.3) | 93.6 | 56.2* | (22.4–141.0) | 143.7* |

| II. Mood disorders | |||||||||||||

| MDE | 28.2 | 2.1* | (1.8–2.4) | 48.7 | 4.4* | (2.6–7.4) | 34.7 | 2.0* | (1.5–2.7) | 38.5 | 2.5* | (1.5–4.0) | 8.2* |

| Dysthymia | 5.0 | 3.2* | (2.4–4.3) | 10.0 | 5.0* | (2.1–12.0) | 9.6 | 5.0* | (2.9–8.8) | 14.6 | 8.9* | (4.2–18.8) | 6.9 |

| Bipolar I or II disorders | 7.1 | 2.8* | (2.3–3.5) | 15.5 | 5.1* | (2.7–9.6) | 14.4 | 5.4* | (3.6–7.9) | 33.0 | 13.6* | (8.0–23.2) | 52.3* |

| Any mood disorder | 36.0 | 2.5* | (2.2–2.8) | 64.2 | 7.1* | (4.1–12.3) | 50.0 | 3.3* | (2.4–4.5) | 73.3 | 10.0* | (5.0–19.9) | 35.3* |

| III. Impulse-control disorders | |||||||||||||

| ADHD | 11.7 | 2.3* | (1.6–3.3) | 28.8 | 3 | 3 | 13.0 | 2.6* | (1.5–4.5) | 36.2 | 3 | 3 | 20.0* |

| ODD | 13.6 | 2.5* | (1.8–3.5) | 12.2 | 3 | 3 | 13.0 | 2.4* | (1.5–3.7) | 27.6 | 3 | 3 | 7.3 |

| Conduct disorder | 12.3 | 1.9* | (1.4–2.6) | 12.4 | 3 | 3 | 21.7 | 4.2* | (2.8–6.4) | 22.5 | 3 | 3 | 18.8* |

| IED | 7.8 | 1.7* | (1.3–2.2) | 21.8 | 5.3* | (2.4–11.6) | 11.8 | 2.5* | (1.4–4.4) | 9.0 | 1.7 | (0.8–3.6) | 9.5* |

| Any impulse-control disorder | 33.7 | 2.3* | (1.8–2.8) | 63.2 | 3 | 3 | 47.2 | 4.3* | (2.8–6.6) | 59.5 | 3 | 3 | 24.6* |

| IV. Substance use disorders | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 19.3 | 2.2* | (1.8–2.7) | 27.0 | 3.2* | (1.5–6.7) | 25.0 | 3.5* | (2.5–4.9) | 37.3 | 5.6* | (2.7–11.5) | 11.5* |

| Alcohol dependence | 8.5 | 2.4* | (1.8–3.2) | 14.2 | 4.0* | (1.6–9.7) | 12.8 | 4.1* | (2.6–6.3) | 23.4 | 7.3* | (3.0–17.6) | 12.1* |

| Illicit drug abuse or dependence | 13.0 | 2.4* | (1.8–3.0) | 17.7 | 3.4* | (1.6–7.3) | 17.5 | 3.6* | (2.3–5.4) | 20.6 | 3.9* | (2.1–7.2) | 7.3 |

| Illicit drug dependence | 5.6 | 3.0* | (2.0–4.4) | 10.6 | 5.8* | (2.1–16.0) | 9.1 | 5.2* | (3.1–8.7) | 9.3 | 4.6* | (1.9–10.9) | 6.0 |

| Any substance use disorder | 21.4 | 2.2* | (1.8–2.6) | 31.4 | 3.5* | (1.8–6.9) | 27.0 | 3.3* | (2.4–4.5) | 37.3 | 4.8* | (2.4–9.5) | 9.8* |

| V. Any disorder | 71.9 | 3.3* | (2.8–4.1) | 100.0 | -- | -- | 83.1 | 6.5* | (3.7–11.7) | 100.0 | -- | -- | 5.3* |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Based on a separate multivariate logistic regression equation for each row of the table in which dummy variables defining the four panic subgroups are used to predict lifetime occurrence of the comorbid disorder controlling for age at interview (in five-year age intervals), sex and race-ethnicity. ORs compare respondents in each of the four panic subgroups with respondents who have no lifetime history of panic.

PA-only = lifetime history of panic attack but not panic disorder or agoraphobia; PA-AG = lifetime history of panic attack with agoraphobia but not panic disorder; PD-only = lifetime history of panic disorder without agoraphobia; PD-AG = lifetime history of panic disorder with agoraphobia.

Insufficient precision for estimation due to the low prevalence of PA-AG and PD-AG

Twelve-month clinical severity and role impairment

Summary PDSS ratings of clinical severity vary significantly across the four 12-month panic subgroups (χ23 = 34.3–102.9, p < .001), with the highest ratings in the PD-AG subgroup (86.3% moderate or severe, 42.40% severe) and the lowest in the PA-only subgroup (6.7% moderate or severe, 0.3% severe). (Table 4) Respondents in the PA-AG subgroup have higher PDSS ratings (45.3% moderate or severe, 20.2% severe) than those in the PD-only subgroup (46.1% moderate or severe, 6.0% severe).

Table 4.

Clinical severity and role impairment among respondents in four mutually exclusive 12-month panic subgroups

| PA-only1 | PA-AG1 | PD-only1 | PD-AG1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ23 | |

| I. Clinical severity (Panic Disorder Severity Scale)2 | |||||||||

| Severe | 0.3 | (0.2) | 20.2 | (7.1) | 6.0 | (2.5) | 42.4 | (8.0) | 34.3* |

| Moderate | 6.4 | (0.8) | 25.1 | (7.9) | 40.1 | (4.8) | 43.9 | (10.1) | 102.9* |

| Mild | 14.9 | (2.0) | 25.1 | (5.6) | 37.8 | (5.7) | 13.7 | (4.5) | 61.9* |

| None | 78.4 | (2.2) | 29.6 | (8.3) | 16.1 | (4.4) | 0.0 | (0.0) | -- |

| II. Impairment (Sheehan Disability Scales)3 | |||||||||

| Severe | 11.1 | (1.1) | 39.0 | (7.9) | 56.2 | (5.0) | 84.7 | (5.3) | 108.4* |

| Moderate | 10.2 | (1.5) | 19.8 | (8.0) | 20.6 | (4.4) | 10.3 | (5.0) | 119.8* |

| Mild | 8.1 | (1.2) | 11.7 | (5.9) | 13.8 | (3.1) | 5.0 | (3.0) | 62.9* |

| None | 70.6 | (2.0) | 29.4 | (8.8) | 9.4 | (3.3) | 0.0 | (0.0) | 62.9*5 |

| (n) 4 | (701) | (37) | (120) | (41) | |||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

PA-only = lifetime history of panic attack but not panic disorder or agoraphobia; PA-AG = lifetime history of panic attack with agoraphobia but not panic disorder; PD-only = lifetime history of panic disorder without agoraphobia; PD-AG = lifetime history of panic disorder with agoraphobia.

The original PDSS categories of severe and very severe were collapsed to define the severe category reported here.

Responses to the four SDS questions (impairments in function in work, home, social, and personal relationship functioning) were combined by assigning respondents their most severe score across the four. The original SDS categories of severe and very severe were collapsed to define the severe category reported here.

The number of respondents in each subgroup who reported 12-month prevalence does not equal the sample size in Table 1 multiplied by the estimate of 12-month persistence in that table due to the fact that persistence is estimated on weighted data and the sample sizes report the actual numbers of (unweighted) cases.

As the number of respondents with at least mild impairment is the additive inverse of the number with no impairment, the χ2 value in this row is identical to the value in the preceding row.

Summary SDS ratings of role impairment are similar to PDSS ratings in being highest in the PD-AG subgroup (95.0% moderate or severe, 84.7% severe) and lowest in the PA-only subgroup (21.3% moderate or severe, 11.1% severe). Unlike PDSS ratings, though, the PA-AG subgroup has lower SDS ratings (58.8% moderate or severe, 39.0% severe) than the PD-only subgroup (76.8% moderate or severe, 56.2% severe), although the modal rating is severe in all three subgroups other than PA-only. In the latter, the modal rating is no disability (70.6%).

Treatment

The vast majority of PD cases obtained lifetime treatment for psychiatric problems, although somewhat more so among those with AG (96.1%) than without (84.8%). (Table 5) Lifetime treatment proportions are lower in the PA-AG (74.7%) and PA-only (61.1%) subgroups. The proportions that obtained panic-specific treatment are only slightly lower than overall treatment in the PD-only (70.3 vs. 84.8%) and PD-AG (85.0% vs. 96.1%) subgroups, but substantially lower in the PA-only (16.2% vs. 61.1%) and PA-AG (37.6% vs. 74.7%) subgroups. The most common site of treatment was the general medical sector in three of the four subgroups (32.3–70.4%). The exception is PA-AG, where non-MD mental health treatment (46.1%) is slightly more common than general medical treatment (42.7%).

Table 5.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment of respondents in four mutually exclusive panic subgroups

| PA-only1 | PA-AG1 | PD-only1 | PD-AG1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | χ232 | |

| I. Lifetime treatment | |||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 24.2 | (1.2) | 39.4 | (6.6) | 37.9 | (2.5) | 58.4 | (4.9) | 58.5* |

| Other mental health | 26.5 | (1.3) | 46.1 | (7.1) | 38.0 | (2.8) | 48.1 | (4.2) | 32.7* |

| General medical | 32.3 | (1.2) | 42.7 | (6.4) | 56.0 | (2.9) | 70.4 | (4.9) | 88.1* |

| Human services | 15.1 | (1.3) | 26.6 | (6.1) | 17.6 | (2.3) | 16.5 | (4.1) | 4.7 |

| CAM | 15.9 | (1.0) | 35.5 | (7.1) | 19.1 | (1.9) | 28.3 | (4.7) | 31.0* |

| Panic-specific treatment | 16.2 | (1.2) | 37.6 | (6.6) | 70.3 | (2.8) | 85.0 | (4.3) | 101.1* |

| Any treatment | 61.1 | (1.3) | 74.7 | (5.4) | 84.8 | (1.8) | 96.1 | (1.7) | 107.5* |

| (n) | (1672) | (71) | (344) | (105) | |||||

| II. Twelve-month treatment | |||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 12.1 | (1.8) | 21.6 | (7.4) | 27.2 | (4.7) | 34.6 | (7.1) | 24.7* |

| Other mental health | 15.2 | (1.4) | 21.1 | (8.1) | 28.7 | (4.7) | 41.0 | (6.4) | 33.8* |

| General medical | 25.5 | (1.7) | 30.6 | (7.9) | 46.0 | (5.0) | 45.1 | (7.4) | 25.1* |

| Human services | 8.5 | (1.2) | 21.6 | (7.3) | 12.7 | (3.0) | 14.3 | (6.1) | 7.7 |

| CAM | 6.2 | (1.0) | 11.7 | (5.7) | 9.7 | (3.0) | 15.9 | (5.8) | 7.5 |

| Panic-specific treatment | 14.7 | (1.4) | 29.7 | (8.9) | 43.9 | (4.5) | 52.7 | (7.3) | 123.7* |

| Any treatment | 45.7 | (2.4) | 60.8 | (8.4) | 66.9 | (4.6) | 72.6 | (6.5) | 24.3* |

| Guideline-concordant treatment | 18.2 | (1.7) | 40.6 | (9.0) | 45.1 | (5.0) | 54.9 | (6.3) | 54.5* |

| (n) | (701) | (36) | (120) | (42) | |||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

PA-only = lifetime history of panic attack but not panic disorder or agoraphobia; PA-AG = lifetime history of panic attack with agoraphobia but not panic disorder; PD-only = lifetime history of panic disorder without agoraphobia; PD-AG = lifetime history of panic disorder with agoraphobia.

This set of statistics tests the significance of the differences among the four percentages in each row

As with lifetime treatment, the proportion of 12-month cases that received treatment in the year before interview is highest in the PD-AG subgroup (72.6%), lowest in the PA-only subgroup (45.7%), and intermediate in the PA-AG (60.8%) and PD-only (66.9%) subgroups. Also similar to the lifetime treatment data, 12-month panic-specific treatment made up a higher proportion of all treatment in the PD-only (43.9% vs. 66.9%) and PD-AG (52.7% vs. 72.6%) subgroups than in the PA-only (14.7% vs. 45.7%) and PA-AG (29.7% vs. 60.8%) subgroups. Twelve-month treatment was obtained in the general medical sector more often than in any other sector in each of the four subgroups (25.5–46.0%). The proportion of 12-month cases that obtained treatment consistent with basic treatment guidelines did not differ markedly across the three subgroups with PD or AG (40.6–54.9%). Although treatment meeting basic guidelines was received by a substantially lower proportion of patients in the PA-only subgroup (18.2%), it is important to remember that published treatment guidelines apply to panic disorder and agoraphobia, not to isolated panic attacks.

COMMENT

These results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The response rate was only 70%. As described in more detail elsewhere,15 we assessed this problem in a non-respondent survey where a sub-sample of initial non-respondents was offered a large financial incentive ($100) to complete a short (15-minute) telephone interview that included CIDI diagnostic stem questions. No significant difference was found in panic stem question endorsement compared to the main survey sample, indirectly arguing against large non-response bias on the basis of panic. Second, although good concordance with SCID PD diagnoses was found, no validity data were obtained for PA or AG. Third, information about AOO, persistence, and other important course and treatment variables were obtained retrospectively that could be biased. As described in more detail elsewhere,16 a number of strategies were used in the NCS-R to reduce recall bias. Evidence exists that these strategies improved accuracy of retrospective AOO reports,30 but we have no data about effects on other aspects of recall.

With these limitations as a backdrop, the NCS-R lifetime prevalence estimates of DSM-IV PD and PD-AG (4.7%, 1.1%) are similar to the DSM-III-R estimates in the baseline NCS (3.5%, 1.5%). The NCS-R estimate of PD-only prevalence (3.7%) is substantially higher than in the NCS (2.0%).2 Although higher than in earlier epidemiological surveys,31 the concordance of the NCS-R PD prevalence estimate with an independent SCID estimate argues against upward bias. In the case of AG, the concern is more with downward than upward bias based on the fact that the CIDI requirement of anxiety about multiple situations is stricter than the DSM-IV requirement.

Estimates of persistence, socio-demographic correlates, and psychiatric comorbidity are broadly consistent with the baseline NCS1, 2, 32 and other previous epidemiological surveys,14, 31, 33–35 although direct comparison is not possible because previous surveys did not disaggregate panic into the four subgroups considered here. High prevalence among women, low prevalence among the elderly, and strong comorbidity with other anxiety and mood disorders are all noteworthy consistencies with previous surveys. One notable difference is a much higher estimated lifetime prevalence of panic attacks in the NCS-R (28.3%) than the NCS (7.3%), a discrepancy presumably due to the more detailed stem questions in the DSM-IV version of the CIDI than in the DSM-III-R version that suggests panic attacks were underestimated in the baseline NCS.

We are aware of no previous general population research that compared the prevalence and correlates of isolated panic attacks versus panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. The most striking results of this comparison are that isolated panic attacks are both quite common and significantly comorbid with other DSM-IV disorders. These results are consistent with clinical studies.36, 37 The vast majority of people with isolated panic attacks fail to meet PD criteria because they never had recurrent uncued attacks, although they typically had numerous cued attacks. Another notable subgroup results is that cued attacks are more common than uncued attacks even among people with PD. This is especially striking given that probing often uncovers initially unrecognized panic cues,38, 39 which means that the NCS-R probably underestimates the proportion of attacks that are cued. We also found that persistence and number of lifetime attacks are more strongly related to PD than AG, that comorbidity, especially with other anxiety disorders, is more strongly related to AG than PD, and that isolated panic attacks are associated with substantial role impairment when they occur in conjunction with AG.

The subgroup results suggest that AG and PD are to some extent distinct, as about 40% of all respondents with PA and AG never met criteria for PD. This finding is consistent with family aggregation studies, which show that risk of AG is significantly elevated among relatives of people with PA-AG43 and relatives of people with PD-AG compared to PD-only.39,40 Family genetic studies also suggest that AG and PD may have at least some distinct pathogenic mechanisms.41,42 At the same time, our finding of higher conditional prevalence of AG among people with PD than PA is consistent with the strong association between AG and PD long observed in clinical settings.

The subgroup results document monotonic increases from PA-only to PD-AG in number of attacks, comorbidity, clinical severity, role impairment and treatment seeking, with intermediate values for PA-AG and PD-only. Together with the finding that a high proportion of AG is associated with PA, these results could be interpreted as suggesting that panic exists along a continuum in which PA and PD differ in degree rather than in kind. This interpretation is consistent with prior findings that infrequent, spontaneous panic attacks are common in the general population,40, 41 that these attacks typically include fewer and less severe symptoms than those of patients with PD,42 and that infrequent PA aggregates with PD in families.43, 44

The distinction between cued and uncued attacks might be called into question as part of this same line of thinking based on the view that the vast majority of panic attacks are to some extent cued.37, 45, 46 It would be premature to conclude from these results that the boundary between PA and PD is arbitrary. Nevertheless, given the high prevalence of PA-only and the negative outcomes associated with PA-only, future research might profitably attempt to subset PA-only and evaluate whether diagnostic criteria or symptom thresholds for panic disorder should be modified to improve differentiation between pathological and normal panic experiences.

An innovation of the NCS-R was the use of a fully structured version of the PDSS to assess clinical severity. Although lower than in clinical samples, close to 90% of respondents with PD-AG and roughly 50% of those with PA-AG and PD-only were found to be in the clinically significant range on the PDSS. A related finding is that both clinical severity assessed in the PDSS and role impairment assessed in the SDS appear to be influenced nearly as much by agoraphobia (PA-AG vs. PA-only) as panic disorder (PD-only vs. PA-only). This is consistent with prior findings that AG is associated with panic severity, anticipatory anxiety, and cognitive correlates of severity40, 47–49 and our finding that AG is more common among people with PD than PA. Also consistent with this pattern is the higher average number of lifetime panic attacks among respondents with versus without AG in both the PA and PD samples. One possible interpretation of this pattern is that AG is a severity marker of panic, although this is at least superficially inconsistent with the notion in the last paragraph that AG is distinct from PD disorder. Another possibility is that AG has a direct effect on impairment.

The treatment results are consistent with previous NCS-R reports that most people with PD eventually obtain treatment,23 that most active cases receive treatment in a given year,50 and that most current treatment (45–60% across the three PD and-or AG subgroups) fails to meet basic treatment guidelines.50 The latter result is all the more striking in that our definition of treatment quality is liberal. For example, no distinction was made among psychotherapies despite much more evidence for the effectiveness of some types of psychotherapy than others in treating panic.51–53 Nor was a distinction made among antidepressants or anxiolytics despite much more evidence for the effectiveness of some than others.54, 55 In interpreting the finding that many patients fail to receive guideline-concordant treatment, it should be recognized that some patients were so classified because they dropped out of treatment prematurely rather than because treatment providers delivered inappropriate care. Both problems need to be addressed in future practice-oriented research.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by NIMH (U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (New York State Psychiatric Institute, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry; Technical University of Dresden). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs.

Send correspondence to ncs@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. R13-MH066849-03 (Heeringa), R01-MH069864-02 (VonKorff), R01-DA016558-02 (Anthony).

References

- 1.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, Magee WJ. Panic and panic disorder in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:413–420. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheikh JI, Leskin GA, Klein DF. Gender differences in panic disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:55–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke KC, Burke JD, Regier DA, Rae DA. Age of onset of selected mental disorders in five community populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:511–518. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity. In: Wetzler S, Sanderson WC, editors. Treatment Strategies for Patients with Psychiatric Comorbidity. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen H-U, Ustun TB, Roy-Byrne PP, Walters EE. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:801–808. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, Ustun B, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:229–235. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Johnson J, Greenwald S. Panic attacks in the community. Social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA. 1991;265:742–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Lish JD, Klerman GL. Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:984–992. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wittchen HU, Essau CA. Epidemiology of panic disorder: progress and unresolved issues. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27 (Suppl 1):47–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90017-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin RD, Gotlib IH. Panic attacks and psychopathology among youth. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:216–221. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed V, Wittchen HU. DSM-IV panic attacks and panic disorder in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: how specific are panic attacks? J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katschnig H, Amering M. The long-term course of panic disorder and its predictors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:6S–11S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199812001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Romanoski A, et al. Onset and recovery from panic disorder in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:501–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shear MK, Rucci P, Williams J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale: replication and extension. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, Rucci P. Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15:183–185. doi: 10.1002/da.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, editors. Textbook of Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halli SS, Rao KV, Halli SS. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York, NY: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.[computer program] Version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knäuper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:305–309. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of psychiatric comorbidity. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GEP, editors. Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joyce PR, Bushnell JA, Oakley-Browne MA, Wells JE, Hornblow AR. The epidemiology of panic symptomatology and agoraphobic avoidance. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobi F, Wittchen HU, Holting C, et al. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS) Psychol Med. 2004;34:597–611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. 12-Month comorbidity patterns and associated factors in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004:28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barlow DH, Vermilyea J, Blanchard EB, Vermilyea BB, Di Nardo PA, Cerny JA. The phenomenon of panic. J Abnorm Psychol. 1985;94:320–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craske MG. Phobic fear and panic attacks: The same emotional states triggered by different cues? Clin Psychol Rev. 1991;11:599–620. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craske MG. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to panic and agoraphobia. In: Dobson KS, Craig KD, editors. Advances in Cognitive-behavioral Therapy. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar]

- 39.White KS, Barlow DH. Panic disorder and agoraphobia. In: Barlow DH, editor. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. pp. 328–379. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapee RM, Murrell E. Predictors of agoraphobic avoidance. J Anxiety Disord. 1988;2:203–217. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittchen H-U, Essau CA. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia. In: Walker JR, Norton GR, Ross CA, editors. Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia: A Comprehensive Guide for the Practitioner. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1991. pp. 103–149. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norton GR, Harrison B, Hauch J, Rhodes L. Characteristics of people with infrequent panic attacks. J Abnorm Psychol. 1985;94:216–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crowe RR, Noyes R, Pauls DL, Slymen D. A family study of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1065–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norton GR, Dorward J, Cox BJ. Factors associated with panic attacks in nonclinical subjects. Behav Ther. 1986;17:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouton ME, Mineka S, Barlow DH. A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:4–32. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24:461–470. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craske MG, Barlow DH. A review of the relationship between panic and avoidance. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:667–685. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Telch MJ, Brouillard M, Telch CF, Agras WS, Taylor CB. Role of cognitive appraisal in panic-related avoidance. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langs G, Quehenberger F, Fabisch K, Klug G, Fabisch H, Zapotoczky HG. The development of agoraphobia in panic disorder: a predictable process? J Affect Disord. 2000;58:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the U.S.: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otto MW, Deveney C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and the treatment of panic disorder: efficacy and strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 (Suppl 4):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:875–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milrod B, Busch F, Leon AC, et al. A pilot open trial of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res. 2001;10:239–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pollack MH. The pharmacotherapy of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 (Suppl 4):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Stein DJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of panic disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:473–482. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]