An 18-year-old woman presented to hospital with a 2-day history of decreased consciousness, nausea and vomiting. She had started taking valproate (750 mg/d) 2 weeks before for the treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. The patient had no history of developmental delay or metabolic defects. She was also taking phenytoin (300 mg/d) and levetiracetam (1000 mg twice daily). She denied having any fever, headaches or other symptoms of neurologic or liver disease.

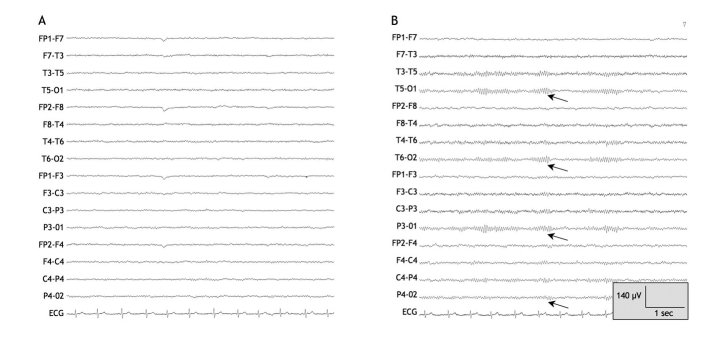

On examination, the patient was drowsy but responsive, and she answered questions appropriately. Her vital signs and the results of a neurologic examination were otherwise unremarkable. The patient had asterixis, but she had no signs of jaundice and no stigmata of chronic liver disease. The findings of the remainder of the physical examination were normal. Results of initial investigations, including a complete blood count and tests for electrolytes, creatinine, liver biochemistry, international normalized ratio and albumin, were normal. The results of a toxicology screen and a head CT scan were unremarkable. The patient's serum valproate level was 507 μmol/L, which was within the therapeutic range (350–700 μmol/L). An electroencephalogram showed diffuse slowing of background activity consistent with metabolic encephalopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Electroencephalogram taken on day 1 after the patient was admitted to hospital for the treatment of valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Note the diffuse high-amplitude generalized slowing, consistent with diffuse cerebral dysfunction. Note: C = central, F = frontal, FP = frontpolar, O = occipital, T = temporal. Odd and even numbers in the electrode locations refer to the left and right hemispheres respectively.

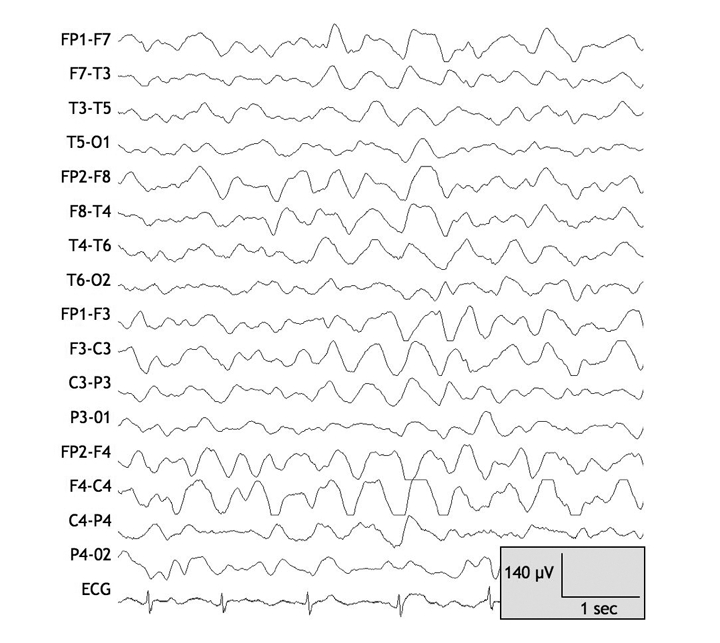

The patient was admitted to hospital for further investigations and for monitoring with video electroencephalography. In the first 48 hours after admission, her level of consciousness fluctuated. Subsequent tests revealed an elevated venous ammonia level (185 [normal 12–47] μmol/L). Her liver biochemistry was normal; thus, valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy was suspected. Valproate therapy was immediately discontinued, and over the next week, the patient's level of consciousness, ammonia level and electroencephalograph results returned to normal (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Electroencephalogram taken on days 4 and 7 after the patient was admitted to hospital: (A) High-amplitude slowing has largely disappeared, and normal 10–11-Hz α waves are becoming apparent in the posterior head regions, suggestive of neurologic improvement. (B) Electroencephalogram appears almost completely normal, with well-developed α waves in the posterior head regions (arrows). Note: C = central, F = frontal, FP = frontpolar, O = occipital, T = temporal. Odd and even numbers in the electrode locations refer to the left and right hemispheres respectively.

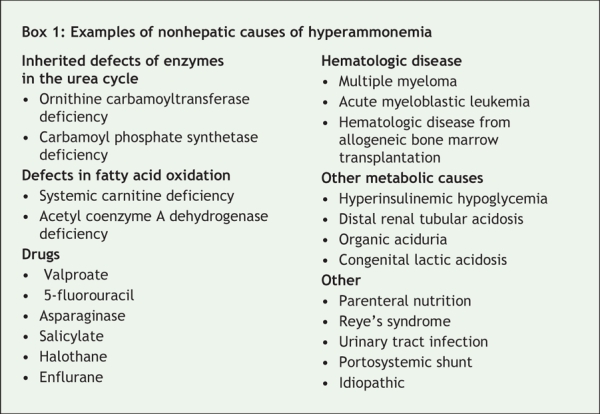

Physicians often attribute encephalopathy and elevated levels of serum ammonia to liver failure. However, other conditions, including valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy, must be considered (Box 1).1 Unfortunately, few physicians are aware of this rare condition. In our case, the clues to the correct diagnosis were the patient's normal hepatic synthetic function and the use of valproate therapy.

Box 1.

Valproate is commonly prescribed for the treatment of seizure disorders, psychiatric conditions, including bipolar disorder, and chronic pain syndromes. Valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy is a rare, but dangerous, adverse event associated with valproate therapy. The typical presentation is the acute onset of impaired consciousness, confusion and lethargy. These initial signs may progress to ataxia, stupor and coma.2–4 Changes seen on an electroencephalogram consist of pronounced generalized slowing and increased epileptiform discharges.

Although the incidence of valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy is unknown, mild and reversible elevations in ammonia have been described in 16%–52% of patients receiving valproate therapy.5 In a case series, asymptomatic hyperammonemia was observed in 52% of patients receiving valproate monotherapy, 55% of those treated with valproate in combination with other anticonvulsants and 8% of patients receiving anticonvulsant regimens that did not include valproate.6 Phenobarbital, and less frequently, phenytoin, carbamazepine and topiramate may exacerbate valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy.5 This condition appears to be more frequent among patients with carnitine deficiency and those with congenital enzymatic defects in the urea cycle.5 Although its pathogenesis is not completely understood, hyperammonemia appears to be the main cause of encephalopathy. Hyperammonemia may arise because of increased renal ammonia production because of reduced glutamine synthesis. The condition may also be due to the inhibition of carbamyl phosphate synthetase or the reduction of hepatic ammonia metabolism owing to decreased carnitine availability, which leads to suppression of fatty acid β-oxidation.5

The management of valproate-related hyperammonemic encephalopathy is generally supportive, with discontinuation of valproate therapy, frequent monitoring, seizure precautions and follow-up electroencephalograms. The indications for valproate therapy extend beyond convulsive disorders; thus, physicians in all areas of practice must be aware of this potentially serious adverse effect.

Saleh Alqahtani MD Liver Unit Division of Gastroenterology Department of Medicine Paolo Federico MD Department of Clinical Neurosciences Robert P. Myers MD Liver Unit Division of Gastroenterology Department of Medicine University of Calgary Calgary, Alta.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hawkes ND, Thomas GA, Jurewicz A, et al. Non-hepatic hyperammonaemia: an important, potentially reversible cause of encephalopathy. Postgrad Med J 2001;77:717-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Segura-Bruna N, Rodriguez-Campello A, Puente V, et al. Valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Acta Neurol Scand 2006;114:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Zaret BS, Beckner RR, Marini AM, et al. Sodium valproate-induced hyperammonemia without clinical hepatic dysfunction. Neurology 1982;32: 206-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Coulter DL, Allen RJ. Secondary hyperammonaemia: a possible mechanism for valproate encephalopathy. Lancet 1980;1:1310-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Verrotti A, Trotta D, Morgese G, et al. Valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2002;17:367-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ratnaike RN, Schapel GJ, Rischbieth RH, et al. Hyperammonemia and hepatotoxicity during chronic valproate therapy: enhancement by combination with other antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 22:100-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]