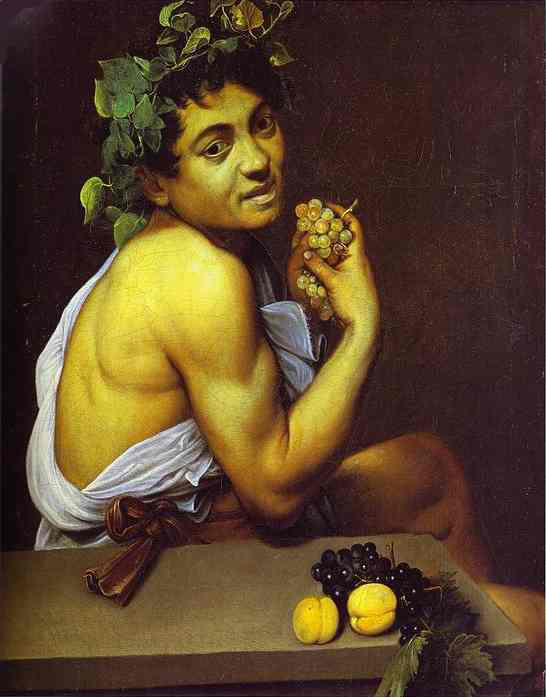

Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610) was born near Bergamo in the town of Caravaggio, whose name he added to his own, and spent his early years there. In 1592, shortly after moving to Rome, he fell ill and spent six months in the hospital of Santa Maria della Consolazione, which had been founded in 1506. Over the next two years he painted the Self-portrait as Sick Bacchus, also known as Bacchino malato (Figure 1). The external sign of Bacchus's (i.e. Caravaggio's) problem is jaundice, as can be seen from the flesh tints, which match those of the peaches on the table in front of him, the slight tinge of yellow in the sclerae, and a comparison of this Bacchus with one that Caravaggio painted in 1596 (Figure 2), an altogether healthier specimen.

Figure 1.

Caravaggio. Self-Portrait as Sick Bacchus (Bacchino Malato) (1594). Oil on canvas, 67 × 53 cm. Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy. [In colour online].

Figure 2.

Caravaggio. Bacchus (1596). Oil on canvas, 95 × 85 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. [In colour online].

The God whom we know as Bacchus was originally called Dionysus, identified in Hesiod's Theogony as the son of Zeus and Semele, the daughter of Cadmus, King of Thebes, and his wife Harmonia. In one version of the story, Zeus's wife, Hera, angered at yet another of her husband's acts of infidelity, visited Semele while she was pregnant and persuaded her to ask Zeus to appear to her in his divine glory. He did so, and she was burned to death by his luminosity. But Zeus rescued the unborn child and kept him in his thigh until he could be born on Mount Nysa, after which he was named.

Dionysus is mentioned only twice in passing in the Iliad and twice in the Odyssey, and there are few other literary references to him before the 5th century BC, although in 6th century vases he is repeatedly depicted as the god of wine. He was first called Bacchus by 5th century Greek playwrights, including Sophocles in Oedipus Rex.

If Caravaggio was jaundiced during his illness, why did he choose to portray himself thus as Bacchus? This is no simple hangover. Bacchus was, of course, ‘affable and hospitable at every hour’, to use the phrase that Hugh Massingberd, one-time obituaries editor at the Telegraph, included among his armament of euphemisms; in other words, a chronic alcoholic. And presumably Caravaggio had seen chronic alcoholics, jaundiced and dying of liver failure due to cirrhosis.

But Caravaggio's Bacchus is a portrait of himself while suffering from an acute illness, from which he eventually recovered. In late 16th century Rome, jaundice of unknown origin was most likely to have been due to acute infective hepatitis, perhaps caused by a zoonosis, such as brucellosis or Q fever.1 However, in playing this game one should not disregard any kind of clue, even the most tenuous. We therefore note with amusement a study in which antibodies to hepatitis C virus were measured in 51 patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia associated with glomerulonephritis, and in 45 controls with non-cryoglobulinaemic glomerulopathies.2 In the patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia, an ELISA assay detected antibodies to hepatitis C virus in 98% of serum samples, whereas the rate was only 2% in the controls. And why is this study relevant? Because it was carried out in the wards and clinics of the Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo and the Ospedale di Treviglio e Caravaggio.

Competing interests None declared.

Funding None.

References

- 1.Pappas G, Christou L, Akritidis NK, Tsianos EV. Jaundice of unknown origin. Remember zoonoses! Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41: 505-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misiani R, Bellavita P, Fenili D, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Ann Intern Med 1992;117: 573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]