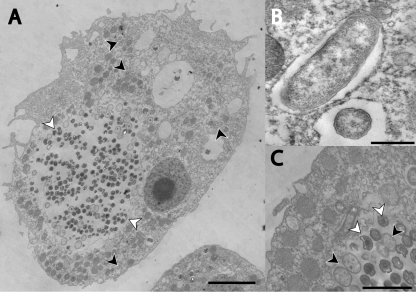

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructure of Acanthamoeba sp. OEW1 and its endosymbionts, Parachlamydia sp. OEW1 and ‘Cand. Procabacter sp. OEW1’. A. Overview of one amoeba trophozoite containing numerous Parachlamydia sp. OEW1 in a large inclusion (white arrowheads) and few rod-shaped ‘Cand. Procabacter sp. OEW1’ (black arrowheads). Bar, 5 μm. B. Close-up on ‘Cand. Procabacter sp. OEW1’ enclosed by a host-derived membrane; a cross and a longitudinal section is depicted. Bar, 0.5 μm. C. Close-up on a Parachlamydia sp. OEW1 inclusion. Reticulate and elementary bodies are readily recognized (black and white arrowheads respectively). Bar, 2 μm. Samples for electron microscopy were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h at room temperature, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at room temperature, prestained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, dehydrated with an ascending ethanol series and embedded in Low Viscosity Resin (Agar Scientific, UK). After polymerization for 16 h at 65°C, samples were cut on an ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut E) with a glass-knife and stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 4 min and 0.3% lead citrate for 2 min. Analysis was performed on a transmission electron microscope (TEM 902, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cultures were embedded in five separate experiments, and a total of approximately 50 amoebal cells were examined closely and showed consistent results. Intervals of at least 1 week separated individual experiments.