Abstract

We investigated the effect of RNAi-mediated gene silencing of 109 Arabidopsis thaliana chromatin-related genes (termed “chromatin genes” hereafter) on Agrobacterium-mediated root transformation. Each of the RNAi lines contains a single- or low-copy-number insertion of a hairpin construction that silences the endogenous copy of the target gene. We used three standard transient and stable transformation assays to screen 340 independent RNAi lines, representing 109 target genes, for the rat (resistant to Agrobacterium transformation) phenotype. Transformation frequency was not affected by silencing 85 of these genes. Silencing of 24 genes resulted in either a weak or strong rat phenotype. The rat mutants fell into three general groups: (i) severely dwarfed plants exhibiting a strong rat phenotype (CHC1); (ii) developmentally normal plants showing a reduced response to three transformation assays (HAG3, HDT1, HDA15, CHR1, HAC1, HON5, HDT2, GTE2, GTE4, GTE7, HDA19, HAF1, NFA2, NFA3, SGA1, and SGB2); or (iii) varying response among the three transformation assays (DMT1, DMT2, DMT4, SDG1, SDG15, SDG22, and SDG29). A direct molecular assay indicated that SGA1, HDT1, and HDT2 are important for T-DNA integration into the host genome in Arabidopsis roots.

Keywords: plant genetic transformation, T-DNA

Research into plant genetic transformation has centered on the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which causes crown gall disease (1). Virulent Agrobacterium strains harbor a tumor-inducing plasmid that, in natural infections, can incite tumors and direct biosynthesis of compounds, called opines, which the bacterium can subsequently use as a carbon and/or nitrogen source (2, 3). Scientists have coopted this system to introduce genes into plant genomes by replacing the plasmid's oncogenes with genes of choice (4).

During infection by A. tumefaciens, a specific segment (transferred-, or T-DNA) of the tumor-inducing plasmid is transferred into the host-plant genome. T-DNA is typically 10–30 kbp in length, contains several genes for phytohormone and opine biosynthesis, and is bounded by tandemly repeated 25-bp border sequences (4). Processing of T-DNA, its transfer from the bacterium to the plant, and its integration into the host genome involve both bacterial and plant proteins (5). The bacterial processes involved in transformation are much better understood than are those taking place in the plant (4–7). Identification of host genes involved in transformation should permit their manipulation to effect more efficient transformation of a broad range of plant species (8).

In recent years, RNA interference (RNAi) has emerged as a promising method to reduce specific gene activities in plants because plants, unlike animals, are not currently susceptible to efficient gene-targeted mutagenesis (9, 10). RNAi is a natural mechanism involved in cellular defense against viruses, genomic containment of retrotransposons, and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression (11–15). In principle, RNAi can silence individual genes, creating knockout phenotypes, either in stable transformants, or upon infection with recombinant RNA viruses that carry the target gene (VIGS, viral-induced gene silencing; 16–18). In reality, RNAi can also reduce activity of related genes in addition to its target, particularly in mammals (19) or affect adjacent but unrelated genes through local heterochromatization (20). These effects can be confounded if the target gene participates in a regulatory network, because its silencing propagates a signal affecting entire genetic systems (15). Thus, RNAi studies have the daunting task to distinguish direct effects on the target, direct effects on genes related to or physically close to the target, and indirect effects on other genes in the same regulatory pathways. Despite these interpretive difficulties, RNAi remains an important technique to reduce gene expression in plants.

This study uses RNAi to identify specific genes involved in Agrobacterium-mediated root transformation. The RNAi was produced from inverted repeats of a subsequence of target genes that, when transcribed, produce a hairpin loop that can serve as a double-stranded RNA substrate for Dicer and the rest of the RNAi machinery (21, 22). These RNAi stocks are part of the extensive collection generated by others in the NSF-sponsored Plant Genome Chromatin Group at the University of Arizona (www.chromdb.org). Our research set out to identify Arabidopsis resistant to Agrobacterium transformation (rat) mutants, by using RNAi directed against particular chromatin genes, to characterize these mutants, and to investigate the roles that several of the silenced genes play in plant transformation.

Results

We set out to identify Arabidopsis chromatin genes that, when inactivated, reduce the frequency of Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. The Functional Genetics of Chromatin Consortium has produced hairpin-transformant Arabidopsis lines directed against a number of chromatin genes. Table 1 lists the 340 independent RNAi lines that we tested. These lines represented 109 distinct genes in 15 gene groups involved in chromatin structure or the availability of DNA for transcription or modification. Because of this involvement, these genes were logical candidates to influence the success of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. We had previously shown that genes encoding histone H2A1 (HTA1) and the histone deacetylase HDT19 were involved in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (14, 23, 32–34).

Table 1.

Summary of tested genes, gene groups, and rat phenotype directed by RNAi

| Genes tested (alternate gene names) | Rat phenotype* (no. of rat mutant lines) |

|---|---|

| Bromodomain proteins | |

| BRD8, BRD12 | None |

| Chromodomain proteins | |

| CRD1 (TFL2, LHP1) | None |

| Chromatin remodeling complex | |

| CHB3, CHB4, CHC1, CHE1 (BSH1), CHR1 (CHA1, DDM1), CHR2 (CHA2), CHR4 (CHA4), CHR5 (CHA5), CHR6 (CHA6), CHR9 (CHA9), CHR10 (CHA10), CHR11 (CHA11), CHR14 (CHA14), CHR15 (CHA15), CHR16 (CHA16), CHR18 (CHA18), CHR19 (CHA19), CHR20 (CHA20), CHR21 (CHA21), CHR22 (CHA22) | CHC1(2), CHR1(1) |

| DNA methyltransferases | |

| DMT1 (MET1, DDM2), DMT2 (MET2), DMT4 (CMT1), DMT5 (CMT2), DMT6(CMT3), DMT7 (DRM2) | DMT1(2), DMT2(1), DMT4(1) |

| Global transcription factors | |

| GTA2, GTC1, GTE1, GTE2, GTE3, GTE4, GTE5, GTE6, GTE7 | GTE2(1), GTE4(2), GTE7(4) |

| Histone acetyltransferases | |

| HAC1, HAC2, HAC4, HAC5, HAF1 (HAC13, GTD1), HAG1 (HAC3), HAG2 (HAC7), HAG3 (HAC8), HAG4 (HAC6), HAG5 (HAC11), HXA1 (HAC9), HXA2 (HAC10) | HAC1(1), HAF1(5), HAG3(2) |

| Histone deacetylases | |

| HDA2, HDA5, HDA6, HDA8, HDA9, HDA14, HDA15, HDA19 (HDA1, HD1), HDT1 (HDA3, HD2A), HDT2, HDT3 (HDA11, HD2c), HDT4 (HDA13, HD2d), SRT1 (HDA12) | HDA15(3), HDA19(2), HDT1(2), HDT2(5) |

| Histone H1 | |

| HON1 (H1–1), HON5 | HON5(1) |

| Methyl-binding domain proteins | |

| MBD1, MBD2, MBD7, MBD8, MBD10, MBD11 | None |

| MAR-binding filament-like protein | |

| MFP1 | None |

| Nucleosome/chromatin assembly factor | |

| NFA1, NFA2, NFA3, NFA4, NFA6, NFB1 (FAS2, MUB3), NFC1, NFC2 (MSI2), NFC4 (MSI4), NFD1(HMGA, HMGa), NFD2, NFD3 (HMGB1), NFD4, NFD5 (HMGD, HMGd), NFD6, NFD7, NFD10 | NFA2(2), NFA3(1) |

| SET domain proteins | |

| SDG1 (CLF, SET1), SDG2 (SET2, ATXR3), SDG3 (SET3, SUVH2), SDG7 (SET7, ASHH3), SDG8 (SET8, ASHH2), SDG9 (SET9, SUVH5), SDG10 (EZA1, SET10), SDG11 (SET11, SUVH10), SDG15 (SET15, ATXR5), SDG17 (SET17, SUVH7), SDG19 (SET19, SUVH3), SDG22 (SET22, SUVH9), SDG25 (SET25, ATXR7), SDG26 (SET26, ASHH1), SDG29 (SET29, ATX5), SDG34 (ATXR6, SET34) | SDG1(1), SDG15(1), SDG22(1), SDG29(1) |

| Silencing group A | |

| SGA1 | SGA1(3) |

| Silencing group B | |

| SGB1, SGB2 | SGB2(1) |

| Silencing group F | |

| SGF1 | None |

| Total: 15 gene groups, 109 genes, 340 lines | 24 genes (46) |

*RNAi directed against genes listed in bold generated a strong rat phenotype; RNAi directed against genes listed without bold generated a weak or variable rat phenotype.

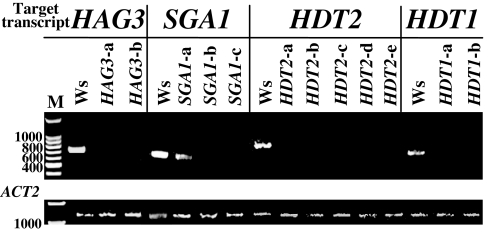

The extent of silencing is documented by RT-PCR at the consortium database (http://chromdb.org). Generally, expression of the targeted gene was undetectable in these lines. We retested several candidate RNAi chromatin lines for gene silencing by using RT-PCR. Fig. 1 demonstrates the effective silencing of these genes in 11 of 12 independently transformed RNAi lines and partial silencing in the remaining line, SGA1-a. Reconstruction experiments indicated that, by using PCR, we could detect transcripts from genes at the following levels per microgram of input cDNA [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]: 20 cycles, HDT1, 100 fg; HDT2, 1 pg; SGA1, 100 fg; 30 cycles, HDT1, 0.1 fg; HDT2, 100 fg; SGA1, 10 fg. During transformation, foreign DNA (the T-strand) must enter the plant cell, reach the nucleus, and become stably inserted into chromosomal DNA. Transformation can be detected by transient GUS expression, generation of a stable transformation phenotype (e.g., tumors or herbicide tolerance), or by detection of T-DNA sequences integrated into high-molecular-weight plant DNA. The first method measures expression of foreign DNA that has reached the nucleus and become double-stranded, but has not necessarily integrated into the genome. The second method reflects the ability of T-DNA to integrate stably into the host genome and to express transgenes. Tumorigenesis assays require that transformed plant cells be able to respond to auxins and cytokinins, whereas antibiotic-resistance assays have no such requirement. The last method directly detects integration of T-DNA into the plant genome without the necessity of transgene expression. Accordingly, transient GUS activity in the absence of stable expression may reflect either lack of T-DNA integration or integration and subsequent transgene silencing. A direct physical assay for T-DNA integration was therefore essential for this investigation because many proteins involved in chromatin structure may also influence transgene expression.

Fig. 1.

Silencing of target chromatin genes in transgenic RNAi Arabidopsis lines. RNA was extracted from roots of wild-type and transgenic RNAi plants and subjected to RT-PCR. As a control, primers were also directed against the Arabidopsis ACT2 gene. Note that in all RNAi lines, transcript levels of the target genes are greatly reduced.

The Arabidopsis root transformation assays were reproducible and robust. Twenty-three independent sets of assays conducted over a 15-month period indicated little variation in transformation efficiency of wild-type roots (percentage of roots showing transformation phenotype: tumorigenesis assays, 70.9 ± 5.2%; antibiotic-resistance assays, 73.1 ± 3.8%; transient GUS-expression assays, 69.4 ± 4.5%). To reduce the possibility that integration of the silencing construct disrupted a gene important for transformation, we investigated at least two independent RNAi lines for each chromatin gene. For each assay, we used several hundred root segments from 10–16 plants for each line. In toto, including the wild-type controls, we tested >400,000 root segments using three standard transformation assays (23). No rat phenotype was encountered for 294 lines representing 85 genes.

We observed weak or strong rat phenotypes for 46 lines, representing 24 genes that fell into 10 gene groups. All rat mutants exhibited either at least a 50% reduction in the tumorigenesis assay relative to the wild-type control or, if a <50% reduction in tumorigenesis frequency, then a consistent production of small or yellow tumors. A strong rat phenotype was reduced by at least 50% in transformation frequency in all three assays, or exhibited small white or yellow tumors and calli (a qualitative difference) if transformation frequency was reduced <50%. A weak rat phenotype was reduced <50% in frequency in all three expression-based transformation assays, although clear qualitative differences from wild-type were seen. Partial rat mutants were within the normal range of transformation for one or two of the assays (23).

These rat mutants comprise three categories: (Category 1) those associated with severely dwarfed plants with low transformation frequency; (Category 2) those with normal plant growth and ability of roots to form callus but with consistently low or reduced transformation frequency with all three assays; and (Category 3) those with normal growth and differing transformation frequency among assays or lines. These three categories appear as different combinations of responses to the three assays in SI Table 3.

Category 1.

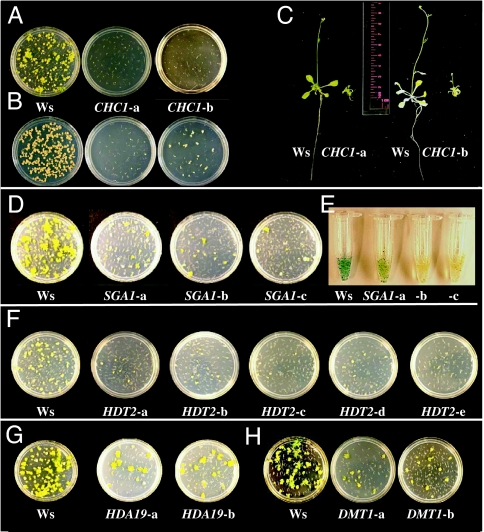

Two RNAi lines silenced for CHC1 (belonging to the chromodomain remodeling complex) exhibited minimal transient and stable transformation frequencies, minimal callus formation on roots, and dwarf morphology (Fig. 2 A–C). These data suggest that CHC1 is not directly related to transformation but, rather, that transformation requires DNA synthesis and mitosis in growing tissues.

Fig. 2.

Effect of inhibition of RNA accumulation for specific chromatin genes on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, callus growth, and plant development. (A) Tumor formation on roots of wild-type (Ws) and two independent RNAi lines targeting CHC1. (B) Callus formation on roots of Ws and two independent RNAi lines targeting CHC1. (C) Inhibition of accumulation of CHC1 mRNA in two independent RNAi lines results in a dwarf phenotype. (D) Tumor formation on roots of Ws and three independent RNAi lines targeting SGA1. (E) Transient GUS activity in roots of Ws and three independent RNAi lines targeting SGA1. (F) Tumor formation on roots of Ws and five independent RNAi lines targeting HDT2. (G) Tumor formation on roots of Ws and two independent RNAi lines targeting HDA19. (H) Tumor formation on roots of Ws and two independent RNAi lines targeting DMT1.

Category 2.

There were 36 lines from 16 genes in eight gene groups that exhibited strongly or weakly reduced response in all three standard tests (tumorigenesis, transient GUS expression, and antibiotic/herbicide resistance in induced calli). These included one line of CHR1 (belonging to the chromatin remodeling complex); seven lines of GTE2, GTE4, and GTE7 (global transcription factor group); eight lines of HAC1, HAF1, and HAG3 (histone acetyltransferases); 12 lines of HDA15, HDA19 (Fig. 2G), HDT1, and HDT2 (histone deacetylases); one line of HON5 (histone H1); three lines of NFA2 and NFA3 (nucleosome/chromatin assembly factor); three lines of SGA1 (silencing group A); and one line of SGB2 (silencing group B). Lines showing a strong rat phenotype contained RNAi constructs directed against HAF1, HAG3, HDT2, and SGA1. All these RNAi lines showed a consistent decrease in transformation susceptibility. Silencing of four genes (GTE7, HDA15, HDA19, and NFA2) resulted in a more variable rat phenotype in all available lines.

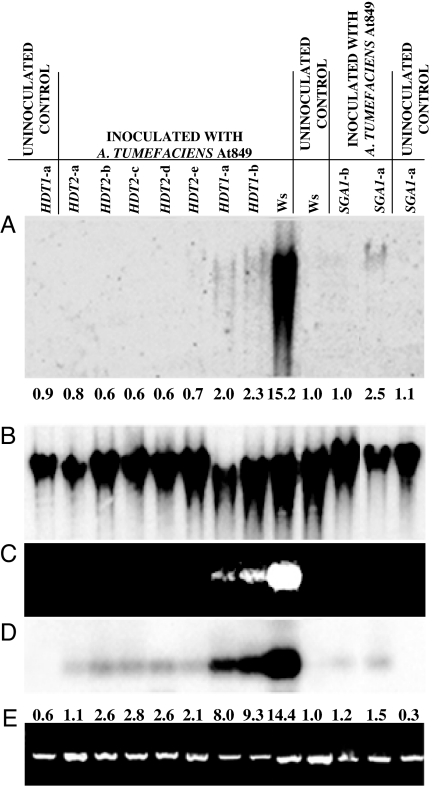

All three transformation assays measure phenotypes derived from transgene expression, not the integration of T-DNA in the plant genome. We therefore tested two strong RNAi rat mutants (SGA1 and HDT2, Fig. 2 D–F; Table 2) and a weaker rat mutant (HDT1; Table 2) for T-DNA integration in a way that does not require transgene expression. Calli were grown from infected root segments in the absence of selection. RNA and DNA were extracted from the calli and assayed for gusA transgene expression and the presence of T-DNA within high-molecular-weight plant DNA. The results in Fig. 3C indicate that the gusA gene was expressed below the detection limit of ethidium bromide staining in the HDT2 and SGA1 lines, whereas it was visibly but weakly stained in both HDT1 lines. DNA blot analysis of the RT-PCR gusA gene products indicated that the gusA transgene was expressed in the SGA1 and HDT2 silenced lines at an ≈3-fold-lower level than in HDT1 RNAi lines (Fig. 3D). Analysis of total genomic DNA from calli grown under nonselective conditions showed a higher level of gusA transgene integration in the HDA1 RNAi lines than in the HDA2 or SGA1 RNAi lines (Fig. 3A). However, integration of T-DNA was 15- to 25-fold less than that observed in calli derived from wild-type Arabidopsis roots. Line SGA1-a integrated 2.5-fold more T-DNA into the plant genome than did line SGA1-b, reflecting the partial rat phenotype of this RNAi line (compare Fig. 2 D and E with Fig. 3 A, C, and D).

Table 2.

Effect of RNAi, directed against selected genes, on transformation of root segments

| RNAi directed against* | Crown gall tumorigenesis†‡ | No. of RNAi segments assayed | Transient GUS activity†§ | No. of RNAi segments assayed | Ppt resistance†¶ | No. of RNAi segments assayed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDT1-a | 54.9–78.4 | 458 | 58.4–81.5 | 418 | 57.8–51.6 | 339 |

| HDT1-b | 53.0–78.6 | 374 | 67.5–81.5 | 305 | 36.3–51.6 | 278 |

| HDT2-a | 23.5–77.3 | 508 | 33.8–78.1 | 681 | 25.3–60.4 | 487 |

| HDT2-b | 14.7–74.3 | 738 | 42.8–77.8 | 862 | 30.6–60.3 | 579 |

| HDT2-c | 18.4–75.2 | 637 | 43.3–78.2 | 829 | 28.6–63.0 | 510 |

| HDT2-d | 20.7–75.4 | 763 | 33.6–70.3 | 1,039 | 22.4–64.6 | 550 |

| HDT2-e | 16.7–74.9 | 777 | 32.4–71.2 | 996 | 25.1–68.7 | 492 |

| SGA1-a | 29.3–72.6 | 783 | 54.5–80.7 | 636 | 51.1–60.6 | 406 |

| SGA1-b | 10.8–72.8 | 798 | 26.5–80.0 | 666 | 40.8–60.1 | 369 |

| SGA1-c | 10.5–82.0 | 582 | 19.4–61.3 | 825 | 18.4–56.2 | 397 |

*Multiple entries for a given gene indicate analysis of independent RNAi lines.

†Data indicate percentage of mutant and wild-type root segments showing the transformation phenotype.

‡Percentage of root segments developing tumors after inoculation with A. tumefaciens A208.

§Percentage of root segments showing transient GUS activity after inoculation with A. tumefaciens At849.

¶Percentage of root segments developing ppt-resistant calli after inoculation with A. tumefaciens At872.

Fig. 3.

Transgene expression and T-DNA integration in wild-type (Ws) and RNAi plants. Roots of wild-type and RNAi lines were infected with A. tumefaciens, and calli were grown in the absence of selection of transgene expression. (A) DNA blot analysis of high-molecular-weight plant DNA isolated from calli. The hybridization probe was the gusA gene located within the T-DNA of the infecting bacterium. (B) Rehybridization of the DNA blot shown in A with an rRNA gene probe indicates the amount of DNA loaded in each lane. (C) RT-PCR analysis of gusA gene expression in the calli. Ethidium bromide staining of RT-PCR products. (D) The gel shown in C was blotted and hybridized with a gusA gene probe. (E) RT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from calli by using primers directed against ACT2 transcripts. Numbers below A indicate the levels of T-DNA signal intensity, as measured by densitometry of the autoradiograph and computed by ImageJ (43) and normalized to the rDNA signal, relative to uninoculated Ws plants, which was arbitrarily set as 1.0. Numbers beneath D indicate the levels of gusA RT-PCR signal intensity, normalized to the ACT2 RT-PCR signal, relative to the uninoculated Ws control, which was arbitrarily set as 1.0.

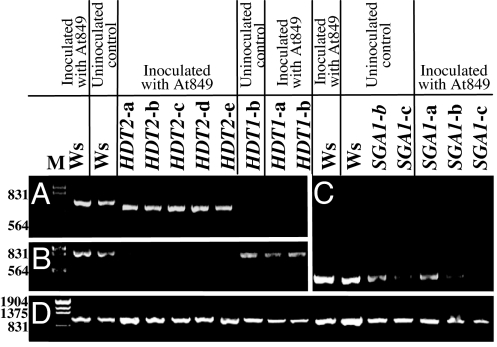

The Arabidopsis HDT1 and HDT2 proteins are 49.2% identical in amino acid sequence. The corresponding regions of the genes used in the RNAi constructions are 58.6% identical, with no continuous regions of identity ≥20 nucleotides. We determined whether silencing of one of these genes resulted in silencing of the other gene. Fig. 4 A and B shows that silencing either HDT1 or HDT2 did not silence the other gene. Furthermore, inoculation of Arabidopsis roots with Agrobacterium did not visibly affect the silencing of HDT1, HDT2, or SGA1 (Fig. 4 A–C).

Fig. 4.

Silencing of target and “off-target” chromatin genes with or without inoculation by Agrobacterium. RT-PCR was used to determine the level of RNA accumulation in roots of wild-type (Ws) and RNAi plants that were either uninoculated or inoculated with A. tumefaciens At849. Ethidium bromide-stained gels are shown. (A) HDT1. (B) HDT2. (C) SGA1. (D) ACT2. Numbers to the left of the gels indicate size (in base pairs).

Category 3.

Eight lines exhibited varying response among the three transformation assays and varying response among lines containing RNAi constructs directed against the same gene. Four lines containing RNAi constructs directed against DNA methyltransferases [DMT1 (Fig. 2H), DMT2, and DMT4] exhibited reduced tumorigenesis but moderately reduced-to-normal callus induction in the presence of kanamycin or phosphinothricin. Four other lines silenced for SET domain protein genes (SDG1, SDG15, SDG22, and SDG29) exhibited high transient GUS activity but greatly reduced tumorigenesis and a high fraction of small, white calli in the presence of kanamycin. The weak and variable rat phenotype displayed by these lines may reflect incomplete silencing of the target gene. Alternatively, these lines may have experienced varying degrees of off-target silencing (19).

Discussion

We screened Arabidopsis lines harboring RNAi constructions, targeted against 109 genes putatively involved in chromatin structure and/or gene expression, for their ability to support genetic transformation of roots by A. tumefaciens. The large majority of these lines showed no obvious defects in plant growth or development, nor did they display substantially altered transformation characteristics. Two independent lines targeting the chromodomain protein gene CHC1 showed a severely dwarfed phenotype when grown either in soil or in culture; these lines also were highly refractory to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in all three standard transformation assays. However, because roots from these plants (the target tissue for transformation) were deformed and did not show normal callus growth in culture, the rat phenotype displayed by these lines likely resulted from abnormally slow root growth rather than from a direct effect of CHC1 on transformation.

Inhibited expression of a few chromatin genes (HDT1, HDT2, and SGA1) had a relatively large effect upon Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Inhibited expression of the histone deacetylase gene HDA19 had a reproducible but lesser effect (Fig. 2G). We previously showed that a T-DNA insertion into HDA19 (formerly known as HD1 or HDA1) disrupted both Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and plant development (14, 23). The HDA19 RNAi lines we tested displayed normal growth and development, suggesting that RNAi inhibition of HDA19 gene expression in these lines was not complete. However, the decrease in transformation susceptibility of these RNAi lines suggests a direct participation of HDA19 in the transformation process.

Although genetic transformation involves the stable introduction of foreign DNA into the host, the introduced genes may or may not be expressed. The importance of chromatin proteins in mediating transgene expression has been well established. For example, mutation of several genes affecting chromatin structure and DNA methylation, including ddm1 (encoding a chromatin remodeling factor), met1 (encoding a DNA methylase), rts1 (encoding the putative histone deacetylase HDA6), and drd1 (encoding a putative SNF2 chromatin remodeling protein), reverses transgene silencing (35–39). Because commonly used transformation assays are based on transgene expression (e.g., resistance to herbicides or antibiotics, tumorigenesis, or transient expression of a reporter protein), host genes thought to mediate transformation may actually mediate a consequence of transformation, transgene expression. We therefore used a biochemical assay to detect directly T-DNA integration into the host genome without the necessity for transgene expression (32). Using this assay, we determined that mutation of several Arabidopsis chromatin genes, including SGA1, HDT1, and HDT2, affects T-DNA integration into the host genome. A similar effect on T-DNA integration was seen with the rat5 mutant, which contains a T-DNA insertion into the histone H2A gene HTA1 (32).

To date, the precise role of any chromatin protein in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has not been determined. It is known that many chromatin proteins are involved in transgene expression. After T-DNA enters the nucleus, chromatin proteins may mediate its targeting to the genome. For example, histones interact with VIP1, a protein that may associate with T-DNA in the cytoplasm and help target T-DNA and associated virulence proteins (the “T-complex”) to the nucleus (40, 41). In addition, chromatin proteins may play an important role in “setting chromatin structure” to allow access of T-DNA to integration break sites in the host genome (42).

Various steps in the transformation process could be mediated by multiple proteins that are functionally redundant. If so, silencing or mutagenesis would need to inactivate all redundant genes to reveal a rat phenotype. We have shown that silencing of several individual genes can inhibit transformation. However, because of the possibility of functional redundancy among the 85 tested genes that did not produce a rat phenotype, these genes may also contribute to transformation. Furthermore, tissue-specific expression of particular genes could prevent their inactivation from affecting transformation of roots. The precise roles of several chromatin proteins in the transformation process await further investigation.

Materials and Methods

Source of RNAi Lines.

A. thaliana RNAi lines were obtained from members of the NSF Plant Genome Chromatin Group based at the University of Arizona (10). These T3 generation lines are homozygous for low- or single-copy insertions of hairpin constructions of chromatin genes (10) (ChromDB website: http://chromdb.org; TAIR website: www.Arabidopsis.org). A. thaliana ecotype Ws was the background used for all assays.

A. tumefaciens Strains and Arabidopsis Root-Transformation Assays.

Three strains of A. tumefaciens were used for transient and stable transformation of the RNAi lines (23). These strains all contain the C58 chromosomal background and C58-derived vir genes. A. tumefaciens A208 (24) incites crown gall tumors, At849 transfers a gusA-intron gene and a plant-active npt II gene (25), and At872 transfers a plant-active bar gene, which confers phosphinothricin resistance on the plants (26). Strains were grown in YEP or AB medium (27) containing the appropriate antibiotics (10 μg/ml rifampicin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin).

Seeds of wild-type (ecotype Ws) and RNAi lines were surface-sterilized and plated in Petri dishes containing B5 medium (Gibco–BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) plus Timentin (100 μg/ml), solidified with 0.75% Bacto-agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) and containing the appropriate selective compound [none for wild-type Ws plants, 20 μg/ml hygromycin, or 10 μg/ml phosphinothricin (ppt)]. After 3 days of incubation at 4°C, seeds were germinated for 4 days under a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod at 25°C before transfer to baby food jars containing B5 medium. Plants were grown for an additional 17 days before being assayed for transformation competence (23).

To overcome physiological variability of individual plants, roots were combined at random from 10–16 plants per line into three to four equal pools. Each pool was divided into three equal sets, one for tumorigenesis assays, one for transient GUS activity assays, and one for ppt or kanamycin resistance assays. Roots were cut into 3- to 5-mm segments and inoculated within a half hour of cutting with the appropriate A. tumefaciens strain, at 108 cfu/ml, suspended in 0.9% NaCl. After 30 min, the root bundles were transferred to Murashige and Skoog medium (Gibco–BRL) for 2 days. For control inoculations, root segments were incubated with only 0.9% NaCl to test the ability of the roots to form callus.

After 2 days, the root bundles were separated into individual segments and transferred to solidified medium containing 100 μg/ml Timentin to kill the bacteria. For transient GUS activity assays, root segments were placed on solidified callus-inducing medium (CIM) (28) for 4–6 days, after which they were stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide (X-gluc) (29) for immediate counting or storage in 70% ethanol. For crown gall tumorigenesis assays, MS medium lacking phytohormones was used. For antibiotic resistance assays, CIM containing either kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or phosphinothricin (10 μg/ml) was used. Stable transformation phenotypes were scored 6 weeks later.

Genomic DNA Blot Analysis.

Calli from uninfected roots and from roots inoculated for 2 days with A. tumefaciens At849 were grown on CIM containing 100 μg/ml Timentin but no plant-selective antibiotics. After 4 weeks, the incipient calli were transferred to liquid CIM containing Timentin and grown with shaking for an additional 3 weeks. The resulting calli were harvested for DNA extraction by using a Qiagen DNAeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total genomic DNA (5 μg) was separated by electrophoresis through 0.7% agarose gels. The DNA was depurinated in the gel by using 0.1 M HCl and transferred onto a Nytran membrane, where it was UV-cross-linked and hybridized (30). DNA hybridization probes were labeled with [32P]dCTP by using Ready-To-Go DNA labeling beads (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The blots were first hybridized with a gusA probe that was PCR amplified from the plasmid pBISN1 (25). After exposure, the blots were stripped and rehybridized with an rDNA probe.

RT-PCR Assays.

Total RNA was isolated from frozen calli by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was also extracted from intact roots of plants grown in baby food jars. The concentration of RNA was measured by using a UV spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and SOFT max PRO software. First-stand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA in a 20-μl reaction using (dT)15 as the reverse primer in the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI) (31). A 2.0-μl aliquot of the first-strand cDNA was amplified for each silenced chromatin gene. PCR was performed by using 0.5 unit of ExTaq (Takara Bio, Madison, WI) DNA polymerase, denaturing at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 20 (Fig. 4) or 30 cycles (Figs. 1 and 3) of 94°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 40 sec, finishing with 72°C for 5 min and holding at 6°C. The 50-μl final reaction volume contained 0.24 μmol of each primer and was 0.25 mM for each dNTP; the different target genes were amplified separately. The primers were: SGA1 5′-TGGACAATCCTGCTCCGTTT-3′ and 5′-CCTGGAGATTTTGTGGCTGAT-3′; HDT2 5′-GTTGCGGTGACACCAAAAA-3′ and 5′-TTCCCTTGCCCTTGTTAGAA-3′; HDT1 5′-TGGAGTTCTGGGGAATTGAA-3′ and 5′-TGGCCTTGTTGTGAGACTCAA-3′; HAG3 5′-TAGCACCATGATTGAGCGTT-3′ and 5′-TTTAGCCAAGCAGAAGCAGT-3′. The Arabidopsis actin gene act2 (5′-ATGGCTGAGGCTGATGATAT-3′ and 5′-TGATCTTGAGAGCTTAGAAA-3′) was the control for constitutive gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles Crane for help with manuscript preparation; Hongbin Cao, Chien-wei Chan, and Joerg Spantzel for help with the assays; and Dr. Gabriela Tenea for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by National Science Foundation Plant Genome Grant 9975930-DBI.

Abbreviations

- rat

resistant to Agrobacterium transformation

- T-DNA

transferred DNA.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706986104/DC1.

References

- 1.Smith EF, Townsend CO. Science. 1907;25:671–673. doi: 10.1126/science.25.643.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chilton WS, Petit A, Chilton M-D, Dessaux Y. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessaux Y, Petit A, Tempé J. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelvin SB. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:16–37. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.16-37.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelvin SB. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:223–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zupan J, Muth TR, Draper O, Zambryski P. Plant J. 2000;23:11–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzfira T, Citovsky V. Mol Plant Pathol. 2001;2:171–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelvin SB. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21(3):95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang C-F, Meyerowitz EM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4985–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerschen A, Napoli CA, Jorgensen RA, Müller AE. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplen NJ, Parrish S, Imani F, Fire A, Morgan RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;96:9742–9747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171251798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang G, Reinhart BJ, Bartel DP, Zamore PD. Genes Dev. 2003;17:49–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakur A. Electron J Biotechnol. 2003;6:39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian L, Wang J, Fong MP, Chen M, Cao H, Gelvin SB, Chen ZJ. Genetics. 2003;165:399–409. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meins F, Jr, Si-Ammour A, Blevins T. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:297–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.114706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burch-Smith TM, Anderson JC, Martin GB, Dinesh-Kumar SP. Plant J. 2004;39:734–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constantin GD, Krath BN, MacFarlane SA, Nicolaisen M, Johansen IE, Lund OS. Plant J. 2004;40:622–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scofield SR, Huang L, Brandt AS, Gill BS. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2165–2173. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.061861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couzin J. Science. 2004;306:1124–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5699.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Moazed D, Grewal SIS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:152–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novina CD, Sharp PA. Nature. 2004;430:161–164. doi: 10.1038/430161a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Nam J, Humara JM, Mysore KS, Lee L-Y, Cao H, Valentine L, Li J, Kaiser AD, Kopecky AL, et al. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:494–505. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.020420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sciaky D, Montoya AL, Chilton M-D. Plasmid. 1978;1:238–253. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(78)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narasimhulu SB, Deng X-B, Sarria R, Gelvin SB. Plant Cell. 1996;8:873–886. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.5.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam J, Mysore KS, Zheng C, Knue MK, Matthysse AG, Gelvin SB. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:429–438. doi: 10.1007/s004380050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtenstein C, Draper J. In: DNA Cloning: A Practical Approach. Glover DM, editor. Vol 2. Oxford: IRL; 1986. pp. 67–119. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam J, Mattysse AG, Gelvin SB. Plant Cell. 1997;9:317–333. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. EMBO J. 1987;6:3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Church GM, Gilbert W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Y, Nam J, Carpita NC, Matthysse AG, Gelvin SB. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1000–1010. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.030726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mysore KS, Nam J, Gelvin SB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:948–953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi H, Mysore KS, Gelvin SB. Plant J. 2002;32:285–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi H, Sardesai N, Fujinuma T, Chan C-W, Veena, Gelvin SB. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1575–1589. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aufsatz W, Mette MF, Matzke AJM, Matzke M. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;54:793–804. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-0179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aufastz W, Mette MF, van der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJM. EMBO J. 2002;21:6832–6841. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furner IJ, Sheikh MA, Collett CE. Genetics. 1998;149:651–662. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanno T, Mette MF, Kreil DP, Aufsatz W, Matzke M, Matzke AJM. Curr Biol. 2004;14:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheid OM, Afsar K, Paszkowski J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:632–637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Krichevsky A, Vaidya M, Tzfira T, Citovsky V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5733–5738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404118102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loyter A, Rosenbluh J, Zakai N, Li J, Kozlovsky SV, Tzfira T, Citovsky V. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1318–1321. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacroix B, Li J, Tzfira T, Citovsky V. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:333–345. doi: 10.1139/y05-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Biophoton Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.