Summary

Dual localisation of proteins at the plasma membrane and within the nucleus have been reported in mammalian cells. Among these proteins are those involved in cell adhesion structures and in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. In the case of endocytic proteins, trafficking to the nucleus is not known to play a role in their endocytic function. Here we show localisation of the yeast endocytic adaptor protein Sla1p to the nucleus as well as to the cell cortex and we demonstrate the importance of specific regions of Sla1p for this nuclear localisation. A role for specific karyopherins (importins and exportins) in Sla1p nuclear localisation is revealed. Furthermore, endocytosis of Sla1p-dependent cargo is defective in three strains with karyopherin mutations. Finally, we investigate possible functions for nuclear trafficking of endocytic proteins. Our data reveal for the first time that nuclear transport of endocytic proteins is important for functional endocytosis in S.cerevisiae. We determine the mechanism, involving an α/β importin pair, that facilitates uptake of Sla1p and demonstrate that nuclear transport is required for the functioning of Sla1p during endocytosis.

Keywords: Karyopherins, Importins, Endocytosis. S. cerevisiae

Introduction

Sla1p is a yeast protein that is proposed to play a role in coupling the actin cytoskeleton to the endocytic machinery in order to facilitate the process of endocytosis. Sla1p has been shown to bind directly to Sla2p (yeast Huntingtin interacting protein-1 HIP1) which itself binds directly to membrane phospholipids and to clathrin light chain (1, 2). Sla1p is also the only protein in yeast known to be responsible for binding a specific cargo (3). Through its central SHD1 domain it is able to bind to the defined NPFX(X)D motif found in a number of proteins that are endocytosed including the pheromone receptors Ste2p and Ste3p. Sla1p regulation of actin dynamics is proposed to occur through interaction with the yeast WASP homologue Las17p, Pan1p a yeast protein with Eps-15 homology domains, and with Abp1p (4-6). All three of these proteins are regulators of the yeast Arp2/3 complex. In higher eukaryotes a number of proteins with characterised roles in endocytosis have been observed to localise to the nucleus (reviewed in (7)). The clearest nuclear localisation of these proteins in mammalian cells was obtained by addition of drugs which inhibit nuclear export. In these cells, certain endocytic proteins were then found in the nucleus. These proteins include eps15, Epsin-1 and α-adaptin (8, 9). Overexpression of epsin also caused it to be observed within the nucleus (10). Nuclear transport of proteins with defined functions at the cell cortex has also been observed for the adhesion protein p120catenin and the developmentally important protein Dishevelled (11, 12). To date the nuclear function of these mammalian proteins has not been shown to be linked to their role in endocytosis. In yeast, one protein Scd5p, has been reported to function in endocytosis and also localise to the nucleus, though its nuclear function does not appear to be coupled to its endocytic role (13).

Results and Discussion

While investigating the role of Sla1p as a protein linking the endocytic machinery to the actin cytoskeleton at the plasma membrane, we observed that a proportion of Sla1p localises to the nucleus (figure 1A). The primary sequence of Sla1p was analysed using a number of web-based prediction programmes to determine whether there are definable nuclear localisation signals (NLSs) or nuclear export signals (NESs) that could facilitate the direct transport of the protein into and out of the nucleus. The sequences identified are shown in figure 1B. The majority of NLSs in Sla1p reside in the N-terminal half of the protein, while the two NESs lie in the central region. We also considered whether other proteins known to play a role in these cortically based processes show localisation to the nucleus. Using antibodies to Abp1p, cofilin, Srv2p/CAP, Sac6p (fimbrin), Sla1p-myc, Sla2p, Las17p-myc as well as rhodamine-phalloidin staining to visualise F-actin we determined that of these only Sla1p showed localisation to the nucleus (figure 1A; data not shown). It should be noted however, that many more proteins are involved in the endocytic process than were tested here and so it remains a clear possibility that other proteins will be identified also within the nucleus see later discussion (14).

Figure 1.

A. Yeast cells (KAY303) expressing myc-tagged Sla1p were grown to log phase and processed for immunofluorecence as described in materials and methods. Co-localisation with the DNA marker DAPI (right panel) was observed. Bar = 5 μm. B. The primary sequence of Sla1p was analysed for nuclear localisation sequences using NucPred, PredictNLS and PSORT online software (http://www.sbc.su.se/%7Emaccallr/nucpred/ http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/predictNLS/ and http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/). Three classic NLSs (265,353,386) were detected in the N-terminal third of the protein, three bipartite NLSs (416, 482, 589) were found in the centre of the protein and two NESs (695, 801) were also detected in the central third of the protein. All numbers given indicate the first residue of the sequence. Domains indicated on the primary structure of Sla1p are: black - SH3 domains; mid-grey - SHD1 domain; light grey - SHD2 domain; stippled - C-terminal repeat region (28).

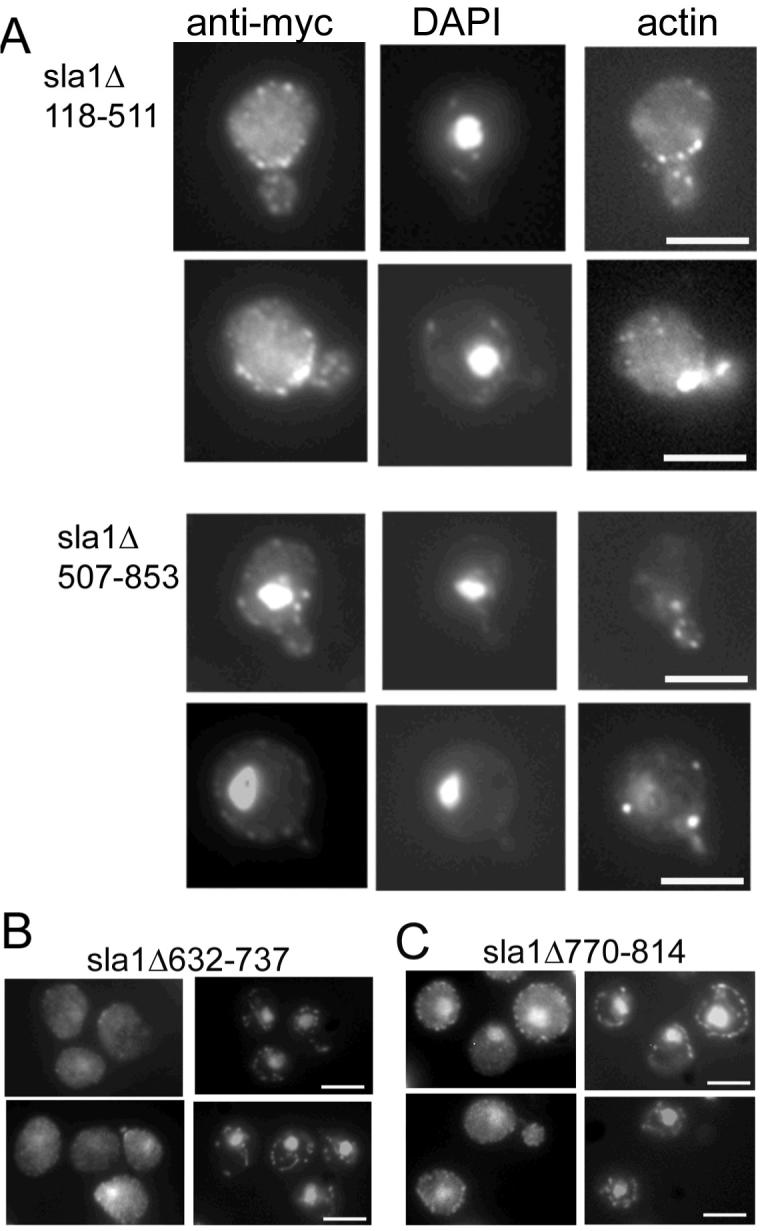

Mutant Sla1 proteins lacking the majority of either NLSs or NESs were expressed in cells lacking the endogenous SLA1. As shown (figure 2A) cells expressing Sla1Δ118-511p which lacks most of the potential NLSs show only a very low level of Sla1p localisation to the nucleus. Conversely, cells expressing Sla1Δ507-853, which lacks putative NESs show very marked localisation of mutant Sla1p to the nucleus with only a small proportion localising to the cell cortex. These two mutants had been studied previously (28) and both were shown to be expressed at wild type levels. Sla1Δ118-511 is able to localise to cortical patches and rescue the ABP1 dependency of a null strain but not the actin organisation phenotype; Sla1Δ507-863 rescues ABP1 dependency and the actin phenotype. We also investigated whether Sla1 mutants with smaller deletions were localised to the nucleus. Mutant Sla1Δ632-737 and Sla1Δ770-814 carry deletions removing each of the NES motifs. Strains expressing both mutations were grown and their exprssion levels and actin localisation were not distinguishable from wild-type. Deletion of the first NES sequence in the strain expressing Sla1Δ632-737 showed a similar level of nuclear localisation as the wild-type strain (figure 2B). However, sla1Δ770-814 in which the second NES is deleted showed an increase in nuclear localisation of Sla1 to a level only slightly less than that observed for the larger deletion Sla1Δ507-863 (figure 2C). These data suggest that this second NES starting at residue 801 is most important in the export of the protein to the cytosol.

Figure 2.

A. Cells expressing mutant forms of Sla1p (Δ118-511, or Δ507-853) were grown to log phase and then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence and staining with rhodamine-phalloidin. Co-staining was achieved by mounting cells in anti-fade solution containing the DNA dye DAPI. In the upper panels Sla1Δ118-511p can be seen to exhibit only staining to punctate cortical sites while in the lower set of panels, cells expressing Sla1Δ507-853 can be seen to show a high level of localisation to the nucleus. B. Strains carrying mutant Sla1 proteins with deletions of either nuclear export signal were generated and cells were grown, then fixed and processed for immunofluorescence. Of the mutants Sla1Δ623-737 gave a low level of nuclear stain similar to wild-type, while the nuclear staining for Sla1Δ770-814 was more marked and resembled the larger deletion shown in panel A. Bars = 5 μm

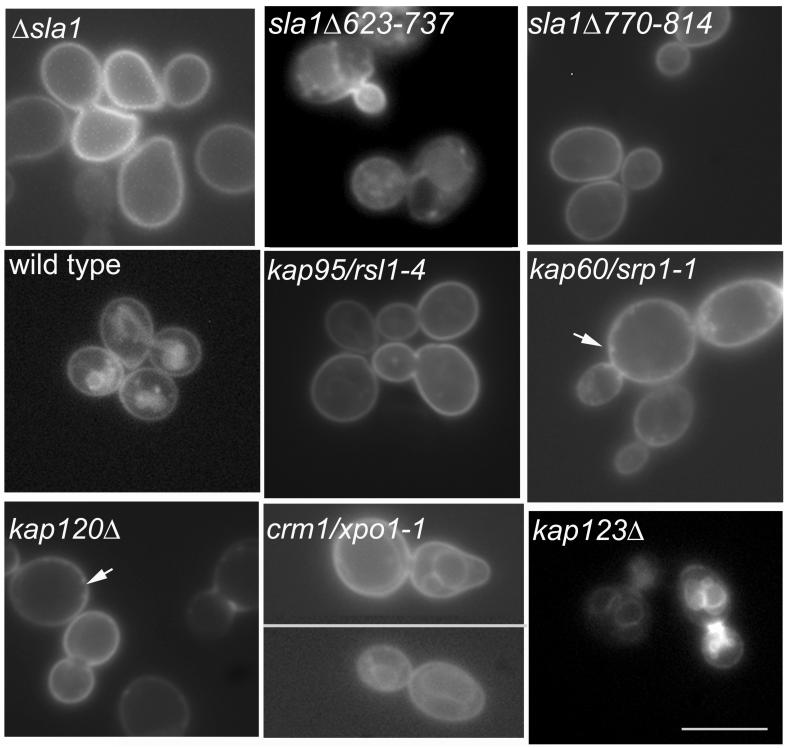

Having demonstrated localisation of Sla1p to the nucleus and having identified potential localisation signals we reasoned that there may be specific uptake or export mechanisms for Sla1p to the nucleus of yeast cells and that this uptake might be coupled to the role of the protein in endocytosis. We obtained yeast strains in which the karyopherins (yeast nuclear importins and exportins) and a number of nuclear transport factors had been either deleted (for non-essential genes) or mutated. We then analysed both the organisation of F-actin and fluid phase endocytosis in the strains. In yeast, there is a well-defined link between organisation of cortical actin patches and endocytosis, and polymerisation of actin is proposed to drive the formation and inward movement of endocytic vesicles (15-18). The summary of results for the mutants is given in Table 1. The phenotype of wild-type and the mutants in which actin and endocytosis were affected is shown in figure 3. Of the 15 mutants tested only 4 showed defects As expected, those mutant strains showing defects in endocytosis, also mostly showed defects in their actin organisation. The extent of the defects is variable possibly suggesting that different karyopherins might be responsible for import of different actin-regulating or endocytic proteins, or that there is redundancy in the transport mechanism. The importins detected as having defects in endocytosis when mutated encode Kap60/Srp1 and Kap95/Rsl1, these proteins form an αβ importin heterodimer in vivo, and Kap60 is the only yeast α-importin (19, 20). The actin defects of these strains are distinct. The Kap60/srp1-31 mutant has small depolarised patches, while the Kap95/rsl1-4 cells often have larger clumps of F-actin (figure 3, left panels). These strains also show a reduction in their fluid phase endocytosis though this is variable with some cells showing clear vacuolar staining (albeit less intense than in wild type cells), while others show plasma membrane staining only (Figure 3, right panels).

Table 1. Phenotypic analysis of karyopherin and nuclear transport mutants.

All strains were grown to logarithmic growth phase and either processed for rhodamine – phalloidin staining to visualise actin organisation, or incubated with Lucifer yellow to determine the efficacy of fluid phase endocytosis (see Materials and Methods). All strains were a gift from Paul Ko-Ferrigno (Cambrige, UK) and Pam Silver (Harvard Med. MA, USA).

| Gene mutated/deleted | Strain # | Morphological and Actin Phenotype | Endocytic Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | PSY1083 | Wild-type (polarised, small punctate patches) | Wild type (mostly, large, single stained vacuole) |

| Wild-type crm1Δ+plasmid borne CRM1 | PSY1104 | Wild-type | Wild type |

| prp20-1/srm1 (Ran1 GEF) | PSY1669 | Cells larger, some depolarisation | Wild-type |

| rna1-1 (Ran1 GAT) | PSY714 | Wild type | Wild-type |

| los1-1 (Ran1 binding) | PSY1140 | Cells larger, some depolarisation | Wild-type |

| Kap60/srp1-31 | PSY731 | Cells often elongated with depolarised actin | Variable, from near normal to little or no uptake |

| Kap95/rsl1-4 | PSY1103 | Cells have larger actin chunks | Variable, from near normal to little or no uptake |

| Kap108/sxm1 Δ | PSY1200 | Wild type | Wild-type |

| Kap111/mtr10 Δ | PSY1175 | Wild type | Wild-type |

| Kap114 Δ | PSY1784 | Wild type | Wild-type |

| Kap119/nmd5 Δ | PSY1198 | Some large cells and actin depolarisation in some budding cells, | Wild-type |

| Kap120 Δ | PSY1082 | Depolarised patches and bent cables | Cells show little or no uptake |

| Kap121/pse1-1 | PSY1201 | Cells elongated with depolarised actin | Wild-type |

| Kap123 Δ | PSY967 | Large cells though most cells have polarised patches | Wild-type, some cells have multiple stained vacuoles |

| Kap124/crm1/xpo1-1 | PSY1105 | Depolarised patches | Cells show little or no uptake |

| Kap142/msn5 Δ | PSY1133 | Wild-type | Wild-type |

Figure 3.

Karyopherin mutants were grown to log phase and then either fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualise the actin cytoskeleton (left panels) or incubated in the presence of the fluid phase marker Lucifer yellow to determine effects on endocytosis (as described in materials and methods). The strains shown here are those that showed marked effects in these assays. Other data are summarised in table 1. Bar = 5 μm.

Two exportins, Crm1p/Xpo1p and Kap120p appeared to show defects actin and endocytosis. Crm1p/Xpo1p is a highly conserved essential yeast exportin with several defined roles including export of ribosomal subunits and export of Pab1p the major mRNA 3′-poly(A)tail binding protein in yeast (21-24). Because of the nature of the proteins it exports, mutations in crm1/xpo1 are likely to have pleiotropic effects. Defects were observed in actin organisation and endocytosis in the crm1/xpo1-1 mutant at both permissive (30°C) and non-permissive temperatures (37°C) (figure 3 and data not shown). We also found similar effects using the leptomycin B sensitive form of Crm1p when expressed in cells (data not shown). Kap120p is less well studied than several other karyopherins. It has however been demonstrated to play a role in export of the large ribosomal subunit (25). Many of the Δkap120 cells had a depolarised actin phenotype (figure 3, left panels). This strain also exhibited a strong defect in fluid phase endocytosis with few cells showing vacuoles of normal appearance and Lucifer yellow staining levels (figure 3, right panels).

We tagged Sla1p with myc in the Kap95/rsl1-4, Kap60/srp1-31 and crm1T539C (leptomycin B sensitive) mutants to determine whether mutations in import and export affect Sla1p localisation. Interestingly, Sla1-myc showed greatly reduced localisation to the nucleus in the rsl1-4 and srp1-31 mutants indicating that these genes encode proteins important for nuclear import machinery for Sla1p (Figure 4A,B). However the crm1 mutant, in the presence or absence of leptomycin B did not show accumulation of Sla1p indicating that export of Sla1p is not mediated by Crm1p (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

To determine whether karyopherins with defects in actin organisation and endocytosis were also affected in their localisation of Sla1p, Sla1p was tagged in three strains and localised as described in materials and methods. As shown, in the srp1-31 and rsl1-4 strains (A,B) Sla1p cannot be observed in the nucleus. In the crm1T539C mutant in the presence of the inhibitor leptomycinB, (LMB at 100 ng/ml for 2 hours). Sla1p can be observed both in the nucleus and at the cell cortex indicating that Crm1 is not the main exportin for Sla1p. Bars = 5 μm.

Having shown that specfic karyopherins exhibit endocytic defects the next question we addressed is whether the nuclear import and export of Sla1p is coupled to its role in endocytosis. As mentioned above, Sla1p is the only characterised binding partner for the endocytic NPFX(X)D motif in S.cerevisiae. We obtained a reporter construct that allows testing of NPFXD mediated uptake (26). In this system NPFXD is fused to the syntaxin Sso1p, which is also fused to GFP (NPF-Sso1-GFP) to allow visualisation. Sla1p is required for uptake of NPF-Sso1-GFP from the plasma membrane (Figure 5). In wild-type cells the protein is seen at the plasma membrane but additionally on internal membranes of endosomes and vacuoles. In cells lacking sla1 expression, there is no uptake at all, and all of the Sso1 protein is found at the plasma membrane (Figure 5). We transformed the plasmid carrying the Sso1 reporter into the Sla1 mutants and into the various karyopherin mutants that showed defects in fluid phase endocytosis, as well as into several others to determine the specificity of any results obtained. Interestingly, 3 of the 4 karyopherins which showed general defects in endocytosis revealed clear defects in uptake of NPF-Sso1-GFP (Figure 5). Only the crm1 mutant showed staining of internal organelles possibly including endocplasmic reticulum. This indicated that the effects on actin and endocytosis by crm1/xpo1 mutation are likely to be indirect or to affect other proteins involved in the process. None of the other karyopherin mutants tested showed any defects in NPF-mediated uptake. The observation that mutations in KAP60, KAP95 and KAP120 prevented normal uptake of the NPF-Sso1 strongly suggests that these proteins are involved in nuclear import and export of the Sla1p protein and that this transport is necessary for the normal role of the protein in endocytosis and actin dynamics. For the Sla1 mutants interestingly Sla1Δ770-814 showed no detectable uptake of the GFP reporter suggesting that the region of the protein involved in nuclear localisation (figure 3) is also important for Sla1p to play its role in endocytosis. The Sla1Δ623-737 mutant lacks the second homology domain (SHD2) of Sla1 (28). In this mutant GFP-NPF-Sso1 is endocytosed by the cells but appears to be unable to be transported to the vacuoles appropriately. This indicates that the SHD2 domain of Sla1p is important for trafficking downstream of the initial endocytic event.

Figure 5.

The reporter construct NPF-Sso1-GFP was transformed into strains as indicated. Uptake of GFP to the endosomal network could be clearly observed in wild-type, xpo1-1/crm1 mutant and a karyopherin mutant (Δkap123) that does not exhibit defects in actin organisation or endocytosis. Little or no detectable uptake was seen in strains Δsla1, sla1Δ770-814, rsl1-4, srp1-31, or Δkap120 while the mutant sla1Δ623-737 showed clear uptake into internal organelles, though little vacuolar staining. Arrows indicate positions of increased brightness at the cell cortex that can be observed in the karyopherin mutants that might highlight vesicles blocked at specific stages of the endocytic uptake. Bar = 10 μm.

Possible roles for Sla1p within the nucleus can be suggested. It could be sequestered in order to limit its activity to appropriate times within the cell cycle. However, during our experiments we saw no shift of localisation away from the plasma membrane to the nucleus in a cell-cycle dependent manner, nor in a way dependent on heat shock, nutritional deprivation, oxidative stress or addition of pheromone (data not shown). While other conditions for sequestration are possible, we currently believe that this is not the primary reason for Sla1p localisation to the nucleus as Sla1p plays a general regulatory role in endocytosis as well as a specific cargo-binding role. A second idea is that Sla1p could affect transcription. This situation would be analogous to that of Epsin-1 which can act as an adaptor at the cell cortex and also can activate transcription through its binding with PLZF (10). Interestingly a genetic interaction with a component of the TFIID complex has been previously reported (27) and a taf14/anc1 deletion shows synthetic lethality with an sla1 deletion. However, we found no co-dependence of localisation between Sla1p and Anc1/Taf14p (data not shown) suggesting that there is no tethering role for the transcription factor though we cannot formally rule out a productive interaction between these proteins in regulating transcription. In a preliminary microarray study the subset of genes affected in an sla1 deletion strain identified a significant number of stress-related genes, indicating that the effect of sla1 deletion on actin organisation and on levels of reactive oxygen species in a cell is likely to have indirect consequences on transcription (28, 29) making a microarray approach unlikely to demonstrate a direct role for Sla1p in transcriptional control, though studies using a partly functional allele of sla1 might allow this approach to be informative. Detection of direct binding to a transcription factor would give the potential to develop a direct transcriptional activation assay to assess a role in this process. A third reason for transport to the nucleus is for a reactivation or priming function. In this scenario, Sla1p could be envisaged to enter the nucleus to be modified such that it could participate in another round of endocytosis. It is known that Sla1p is phosphorylated by the Ark1/Prk1 kinases while at the cell cortex and that this modification causes it to disassemble from the endocytic coat of the invaginating vesicle. Sla1p has also been reported to interact with the major protein phosphatase-1 in yeast Glc7p (30, 31). Glc7p has been reported to localise to the bud neck and the nucleus while Sla1p is found at endocytic sites in both the mother and daughter cell (28, 32, 33). One possibility is that Sla1p, or at least a proportion of the Sla1p, could be dephosphorylated in the nucleus by Glc7p.

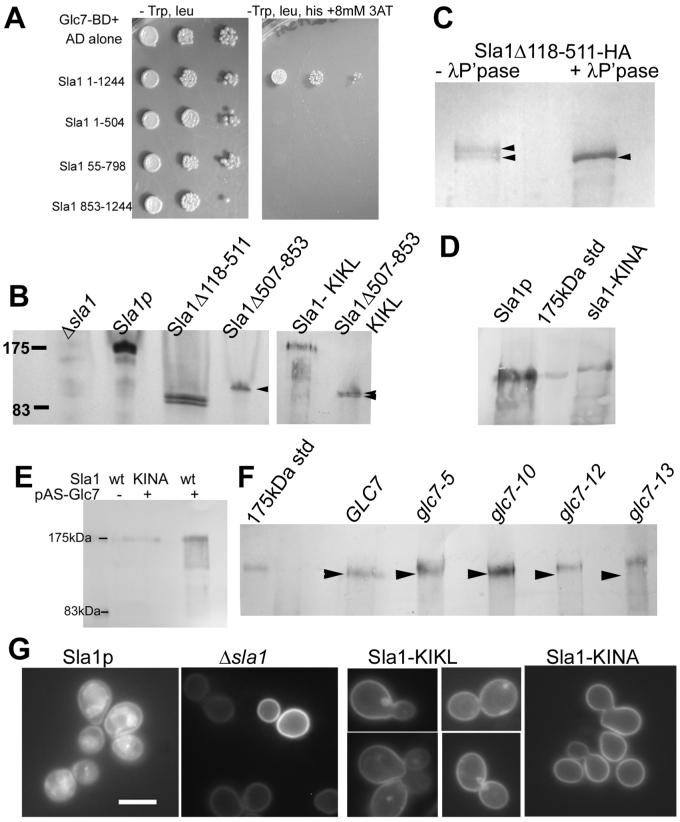

In support of this we firstly repeated and confirmed the two-hybrid interaction between Sla1p and Glc7p. We also investigated interaction with specific mutants of Sla1 (figure 6A). However, even though expression of these domain fusions was verified, we did not observe an interaction with fusions covering the entire length of the protein indicating that two distinct regions of the protein might be involved in the interaction or that the fusion itself abrogates correct folding or display of the binding site. Second, western blotting of the mutant forms of Sla1p revealed that the nuclear excluded form (sla1Δ118-511) runs as a doublet, while the primarily nuclear mutant Sla1Δ507-853 runs as a single band suggesting that movement into the nucleus might facilitate a modification of Sla1p (figure 6B). To demonstrate that the doublet of the nuclear excluded form Sla1Δ118-511 is due to phosphorylation we immunoprecipitated HA-tagged Sla1p and treated it with lambda phosphatase. This treatment led to a single major protein species which had the same mobility as the lower band of the doublet (figure 6C) demonstrating that the higher band of the doublet is due to phosphorylation of Sla1p.

Figure 6. Functional interactions between Sla1p and Glc7p.

A. Two-hybrid interactions were performed to investigate interactions between the protein phosphatase Glc7p and full length or truncated forms of Sla1p.

B. Yeast cells (KAY300) were transformed with plasmids pKA50 (empty), pKA51 (SLA1 full length); pKA53 (sla1Δ118-511); pKA55 (Sla1Δ507-853); pKA438 (Sla1 NF-KL); pKA483 (as pKA55 but additionally NF-KL) and grown in selective media to log phase (plasmids described fully in (28)). Whole cell protein extracts were generated and proteins were separated by PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membrane. The blot was probed with antibodies raised against full length Sla1p. Arrowheads indicate the single and double bands for the Sla1Δ507-853 mutants without or with the KIKL mutation respectively C. Mutant Sla1Δ118-511 was integrated in the genome and HA tagged. It was immunoprecipitated using antibodies against HA. Half the immunoprecipitate was treated with lambda phosphatase as described in materials and methods. The untreated protein runs as a doublet band while the treated protein runs as a single band at a mobility corresponding to the smallest band in the untreated sample.

D. Extracts were made from cells expressing wild-type Sla1 or the KINA mutated form. Blotting revealed that the sla1 KINA mutant runs with reduced mobility indicating an increased size due to lack of dephosphorylation. E. Wild-type and mutant strains were incubated in the presence or absence of a plasmid expressing a Glc7 fusion protein. Extracts were made, separated, blotted and probed using anti-Sla1 antibodies.

F.Glc7 alleles were obtained and the mobility of Sla1p in these strains investigated using western blotting. Glc7-5, glc7-12 and glc7-13 showed increased mobility of Sla1p indicating a reduced interaction between Glc7p and Sla1p. F. Cells (wild-type, Δsla1 or the Sla1-Glc7p binding site mutants, KINF and KINA) were transformed with the NPF-Sso1-GFP reporter and visualised to determine whether mutation of the Glc7p binding motif affected uptake of the tagged syntaxin reporter. Bar = 5μm.

We then mutagenised the single putative Glc7p binding site of Sla1p, KINF (residues 277-280; (34, 35)) in wild type Sla1p to KIKL and to KINA. We were not able to generate the mutation in the two hybrid plasmids due to technical reasons. However, strains expressing both the NF-KL and the NF-KA mutation in Sla1p exhibited apparently normal actin localisation and uptake of the fluid phase marker Lucifer yellow (data not shown). We made extracts of cells expressing the Sla1 KINF mutants and also from cells expressing a NF-KL form of the Sla1Δ507-853 mutant that localised primarily to the nucleus. As shown in figure 6B the Sla1Δ507-853 KIKL mutant now runs as a doublet indicating that the interaction that resulted in formation of the single band (fig 6B lane 4) has been disrupted. While we could not see any clear size difference between wild-type Sla1p and the KIKL mutant we could reproducibly observe an increase in the size of the KIKA mutant on western blotting (Figure 6D). This increase in apparent molecular mass is likely due to an increased proportion of phosphorylated protein caused by abrogation of the interaction between Sla1p and Glc7p phosphatase. Further evidence for a functional interaction between Glc7p and Sla1p was obtained when we western blotted extracts of cells expressing the Glc7 Gal4 binding domain fusion plasmid (pAS-GLC7) for Sla1p. Strikingly, when GLC7 was expressed in this way Sla1p was observed as a series of bands indicating a large number of phosphorylated species (figure 6E). The smallest of these ran at position corresponding to 141 kDa, relatively close to the predicted MW of Sla1p of 136kDa. These bands were not observed in cells lacking the Glc7 plasmid or in cells expressing the Sla1-KINA mutant. These data provide strong evidence for the functional interaction between Sla1 and Glc7p and suggest that in wild-type cells full length Sla1p is hyperphosphorylated. In addition, cell extracts from a number of glc7 mutant alleles were blotted and probed for Sla1p. Of the 4 alleles tested three showed clear reduction in mobility on the gel indicating increased phosphorylation (figure 6F). The effect in the glc7-13 allele was particularly marked (see arrowheads for equivalent position in each lane).

We then determined whether these point mutations affected the ability of cells to take-up the NPF-GFP-Sso1 reporter from the plasma membrane. As shown, the wild-type control shows localisation of GFP reporter throughout the endo-membrane system, and the Δsla1 cells show no uptake (Figure 6G). The mutant KIKL strain shows reduced levels of NPF-Sso1-GFP uptake indicating that association with Glc7p is important for the normal role of Sla1p. Intriguingly, the NPF-Sso1 taken up into some cells does not appear to reach the vacuole rather there is accumulation in a single, organelle often localising adjacent to the vacuole indicating that the Glc7p dephosphorylation of Sla1p may play a role at a second, later step of the endocytic process. Importantly, the KINA mutant that showed a clear increase in size indicating a marked reduction in its dephosphorylation, showed a more marked phenotype than the KIKL mutant. In these cells the GFP-NPF-Sso1 reporter was only observed at the plasma membrane similar to the sla1 null strain.

To consider the possibility that nuclear trafficking could provide a more widespread mechanism for dephosphorylation and thereby reactivation of endocytic coat proteins phosphorylated by the Ark1/Prk1 kinases, we determined whether proteins reported to be phosphorylated by these proteins during endocytosis also have nuclear localisation signals and whether they have also been reported to interact with Glc7p. Other proteins reported to be phosphorylated by Ark1/Prk1 kinases are Pan1p, Scd5p and Ent1p (36, 37). Analysis for NLSs within the primary sequence of these proteins reveals possible sites in all proteins and NucPred (38) scores of 0.9, 0.94 and 0.91 respectively (Sla1p score is 0.93). We then determined whether these proteins have reported interactions with Glc7p. Both Pan1p and Scd5p have been reported to interact with Glc7p in a genome wide study and also in small scale Glc7 interaction studies. It is interesting to note that mammalian orthologues of Pan1p (Eps15) and Ent1 (Epsin) are among those that have been reported to localise to the nucleus (39) suggesting that further investigation might highlight new similarities of regulation of endocytic proteins between yeast and higher eukaryotic cells.

In summary we have shown that, as in higher eukaryotic cells, proteins involved in endocytosis are also able to localise to the nucleus. Specifically we identify the endocytic adaptor protein Sla1p within the nucleus and identify the nuclear uptake mechanism for this protein to be mediated by the importins Rsl1p and Srp1p. Nuclear export involves the exportin Kap120. Unlike the situation in mammalian cells, or for Scd5p in yeast, we have been able to determine a direct link between the functioning of Sla1p in endocytosis and its nuclear trafficking. Finally we show evidence that transport to the nucleus could be coupled to a requirement for Sla1p to be modified to allow its functioning in further rounds of endocytosis. Nuclear trafficking could either allow Sla1p to be dephophorylated by protein phosphatase 1 within the nucleus. Alternatively, Sla1p could ferry Glc7p from the nucleus to the cytoplasm or to forming cortical patches, where it not only dephosphorylates Sla1p, but other phosphorylated endocytic proteins as well.

Materials and Methods

Materials, Strains and Growth Conditions

Unless stated otherwise, chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich(St Louis, Missouri). Media was from Melford Laboratories, Ipswich, Suffolk, UK (yeast extract, peptone, agar) or Sigma (minimal synthetic medium and amino acids). Leptomycin B was a gift from Dr M. Yoshida (Tokyo) and was used at a concentration of 100 ng/ml for 2 hours. Yeast strains used in this study are listed in table 2. Unless stated otherwise, cells were grown with rotary shaking at 30°C in liquid YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, 2% glucose supplemented with 40 μg/ml adenine), except for strains carrying the NPF-Sso1-GFP plasmid which were grown under selection in synthetic media lacking uracil. The mutants Sla1Δ118-511 and Sla1Δ507-853 were integrated into the genome. Plasmids constructed previously pKA53 and pKA55 (28) were linearised using BsiW1 and then integrated into the His3 site of the strain KAY300 (an sla1 deletion strain). New mutation sla1Δ632-737 was made by in vitro mutagenesis to generate Xho1 sites to allow deletion of the SHD2 domain in Sla1; sla1Δ778-814 was made by PvuII deletion of pKA51, followed by religation. These mutant versions of plasmid borne Sla1 were then integrated into the genome as described above. Integration of the mutant genes and expression of the mutant proteins was verified by PCR and western blotting. The proteins were then myc tagged using oligonucleotides to tag the C-terminus with 9x myc or 3xHA tags (40). Oligonucleotides are as described previously (6). Yeast transformations were performed as described (41).

Table 2.

Yeast strains used in this study.

| Strain # | Genotype | Origin/Ref |

|---|---|---|

| KAY300 | MATa, trp1-1, leu 2-3,112, his3-Δ200, ura 3-52, Δsla1::URA3 | (6) |

| KAY303 | MATα, trp1-1, leu 2-3,112, lys2-801, his3-Δ200, ura 3-52, SLA1-9xmyc::TRP1 | (1) |

| KAY351 | MATα his3-200, leu2-3,112, ura 3-52, sla1Δ::LEU2, sla1(Δ118 - 511)::HIS3 | (1) |

| KAY367 | MATα trp1-1, his3-Δ200, leu2-3,112, ura 3-52 Δsla1::LEU2, sla1Δ118-511-9xmyc::TRP1 | (1) |

| KAY382 | MATα, trp1-1, leu 2-3,112, lys2-801, his3-Δ200, Ura 3-52, ΔSla1::URA3, sla1Δ507-853-9xmyc::TRP1 | This study |

| KAY387 | MATα, trp1-1, leu 2-3,112, lys2-801, his3-Δ200, ura 3-52, Δsla1::URA3, sla1Δ507-853::HIS3 | This study |

| PSY1083 | MAT α, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, lys2-801, his Δ 200 | |

| PSY1104 | MAT α, leu2Δ1, ura3-52, lys2-801, hisΔ200, xpo1/crm1Δ+plasmid borne XPO1/CRM1 HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1669 | MATa, ura3-52, trp1Δ63, leu2Δ1, prp20-1/srm1 (Ran1 GEF) | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY714 | MATa, ura3-52, trp1Δ63, leu2Δ1 rna1-1 (Ran1 GAT) | (45) |

| PSY1140 | MATα, ade2-1, can1-100, lys1-1, trp5-48, ura3-1, his5-2, SUP4, los1-1 (Ran1 binding) | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY731 | MAT α, leu2,3-112, ura3-52, his3, ade2, trp1, Kap60/srp1-31 | (19) |

| PSY1103 | MAT a, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, trp1 Δ 63, Kap95/rsl1-4 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1200 | MATa, ura3-52, trp1 Δ 63, leu2 Δ 1, his3 Δ 200, Kap108/sxm1 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1175 | MATa, leu2,3-112, ura3-52, his3 Δ 200, trp1 Δ 1, Kap111/mtr10 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1784 | MAT α, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, his Δ 200, trp1, Kap114 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1198 | MATa, ade2 Δ , ade8 Δ , ura3-52, trp1 Δ 63, leu2 Δ 1, his3 Δ 200, Kap119/nmd5 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1082 | MAT a, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, his Δ 200 Kap120 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1201 | MATa, ura3-52, trp1 Δ 63, leu2 Δ 1, Kap121/pse1-1 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY967 | MAT a, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, his Δ 200 Kap123 Δ ::HIS3 | (20) |

| PSY1105 | MAT α, leu2Δ1, ura3-52, lys2-801, hisΔ200, xpo1/crm1Δ+plasmid borne Kap124/crm1/xpo1-1 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| PSY1137 | MATa, ura3-52, his3 Δ 200, leu2 Δ 1, kap142/msn5 Δ ::HIS3 | P.Silver, P. Ko-Ferrigno |

| Y463 | MATa, leu2, his3, trp1, ura3, Δcrm1::KanR, +plasmid borne CRM1, LEU2 | (46) |

| Y464 | MATa, leu2, his3, trp1, ura3, Δcrm1::KanR, +plasmid borne crm1T539C, LEU2 | (46) |

| PJ694a | MATa trp-901, leu2-3,112, ura3-52, his3Δ200, gal4Δ, gal80Δ,LYS2::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3, GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2 | (42) |

| PJ694α | MATα trp-901, leu2-3,112, ura3-52, his3Δ200, gal4Δ, gal80Δ,LYS2::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3, GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2 | (41) |

| KAY443 | MATa, leu2, his3, trp1, ura3, Δcrm1::KanR, Sla1-9xmyc::TRP1+plasmid borne CRM1, LEU2 | This study |

| KAY444 | MATa, leu2, his3, trp1, ura3, Δcrm1::KanR, Sla1-myc::TRP, +plasmid borne crm1T539C, LEU2 | This study |

| KAY769 | MAT a, leu2 Δ 1, ura3-52, trp1 Δ 63, Kap95/rsl1-4, sla1-9xmyc::TRP1 | This study |

| KAY1040 | MATα trp1-1, his3-Δ200, leu2-3,112, ura 3-52 Δsla1::LEU2, sla1Δ632-737-9xmyc::TRP1 | This study |

| KAY1041 | MATα trp1-1, his3-Δ200, leu2-3,112, ura 3-52 Δsla1::LEU2, sla1Δ770-814-9xmyc::TRP1 | This study |

| KAY1042 | MATα trp1-1, his3-Δ200, leu2-3,112, ura 3-52 Δsla1::LEU2, sla1Δ118-511-3xHA::TRP1 | This study |

| PAY704-1 | MATa glc7ΔLEU2, trp1::GLC7::TRP1, ade2-1, his3-11, leu2-3,112, trp1-1, ura3-1can1-100, ssd1-d2, Gal+ | Mike Stark |

| PAY703-1 | As PAY704-1 but Glc7-5::TRP1 | Mike Stark |

| PAY700-4 | As PAY704-1 but Glc7-10::TRP1 | Mike Stark |

| PAY701-3 | As PAY704-1 but Glc7-12::TRP1 | Mike Stark |

| PAY702-4 | As PAY704-1 but Glc7-13::TRP1 | Mike Stark |

Yeast Two Hybrid Analysis

The yeast two-hybrid screen used bait and activation plasmids, and yeast strains (PJ6904a and α) based on pJ69-2A designed and constructed by Philip James (42). Bait plasmid Glc7-BD was a generous gift from Kelly Tatchell (Louisiana). Activation domain fusion plasmids are as listed in table 3. The bait plasmid was transformed into the MATa strain and the activation domain plasmids into the α strain. The strains were then crossed. Diploids were selected on plates lacking tryptophan and leucine. Diploids were then grow in selective medium and spotted in a 1o fold dilution series onto plates lacking tryptophan, leucine, histidine and containing 8 mM 3′-aminotriazole

Table 3. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Description | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| pAS-Glc7 | Gal4BD-GLC7 TRP1 | (31) |

| pGAD-C1 | 2 hybrid plasmid, LEU2 | (41) |

| pGAD-Sla1 | GAL4-AD-SLA1 LEU2 | Gift from P.Piper (Sheffield) |

| pKA328 | GAL4-AD-SLA1(1-504) | This study |

| pKA344 | GAL4-AD-SLA1(a.a residues55-798) LEU2 | This study |

| pKA506 | GAL4-AD-SLA1(a.a residues 853-1244) LEU2 | This study |

| pKA51 | pRS313+SLA1 | (28) |

| pKA53 | pRS313+Sla1Δ118-511 | (28) |

| pKA55 | pRS313+Sla1Δ507-853 | (28) |

| pKA483 | pRS313SLA1(mutated 279-280 NF to KL) | This study |

| pKA511 | pKA51 (mutated 280 F to A) | This study |

In vitro mutagenesis

Mutagenesis of the putative Glc7p binding site in Sla1p (pKA51 (28)) to generate the mutagenised plasmids pKA438 (NF toKL) and pKA511 (NF to NA) was performed using the Stratagene QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit and following the protocols supplied by the manufacturer (Stratagene, West Cedar Creek, Texas). Oligonucleotide oKA468 and oKA469 were used to generate pKA438 and oKA650 and oKA651 were used to generate pKA511. Further details of constructions are available on request.

Protein methods

Yeast cells (KAY300) were transformed with plasmids pKA50 (empty), pKA51 (SLA1 full length); pKA53 (sla1Δ118-511) and pKA55 (Sla1Δ507-853) and grown in selective media to log phase (plasmids described fully in (28)). Yeast whole cell lysates were prepared as previously described (6) and samples were run on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gels. Gels were then transferred to PVDF membrane, blocked and probed with, affinity-purified rabbit anti-Sla1 antibodies (1). Proteins were detected using anti rabbit alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) at 1:5000 dilution. After probing with an alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody, the blot was washed and incubated with NBT/BCIP developing solution (NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium); 0.5g in 10ml 100% N’N’-dimethylformamide (DMF), stored at 4°C. BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate p-toluidine salt); 0.25g in 10ml DMF, stored at room temp. 66μl NBT stock was added to 10ml alkaline phosphatase buffer (100mM NaCl, 5mM MgCl2, 100mM Tris pH 9.5), and then 66μl BCIP stock was added, mixed and incubated with the blot. After sufficient colour development chromogenic reagent was washed off in water, reaction was stopped by addition of EDTA.

For immunoprecipitation

Cells were grown overnight in selective liquid media lacking tryptophan, this was diluted 1:10 into 150 ml in the morning and allowed to grow to OD600 = 0.5 to 0.7. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1900 xg for 5 minutes and washed once with 30 ml cold 1xPBS. Cell were resuspended in 800 μl lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol. Added 500 μl ice-cold glass beads (Sigma) and 10 μl protein inhibitors (Sigma) and 5 μl of 100 mM PMSF, before vortexing on cell disruptor for 12 minutes at 4°C. Cell lysate was spun at 18,000g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant transferred to clean 1.5 ml eppendorf tube and incubated with 30 μl mouse IgG AC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, sc-2345) for 1 hour on rotation at 4°C. Sample spinned at 1200g for 4 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was split into 2× 400 μl and each aliquot was incubated with 40 μl HA probe F-7 AC mouse monoclonal IgG2a (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, sc-7392AC) for 1 hour at 4°C on rotation. Beads were washed three times with 500 μl lysis buffer, with spinning at 1000 g for 4 minutes at 4°C. 2 × SDS sample buffer was added to one of the sample, boiled for 1 minute and stored at -20°C.

Lambda phosphatase treatment

After the above washing, beads were resuspended in 19 μl lysis buffer, 5 μl MnCl2, 5 μl λ-Phosphatase buffer and 1 μl λ-Phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA P0753S) and incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes, mixing sample several times during incubation. Beads spinned at 1000g for 4 minutes at 4°C, supernatant removed and protein eluted from beads with 20 μl of 2 × SDS sample buffer, boiled for 1 minute and stored at -20°C until use.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Endocytosis of the fluid phase marker lucifer yellow was performed according to the method of Dulic and colleagues (42). Rhodamine-phalloidin (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, California) staining of actin was performed as described (43). Cells were processed for immunofluorescence essentially as described by Ayscough and Drubin (44). Following fixation for 45 minutes with 4% formaldehyde cells adhered to slides with poly-l-lysine were treated for 6 minutes with methanol at −20°C and then for 30 seconds with acetone before incubating with antibodies. Primary antibodies used in this study were A14 anti-myc at a dilution of 1:100 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, California) and anti-Sla1p (used at 1:50 dilution; 28). Both antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight, before washing and incubating with secondary antibodies (fluorescein-isothiocyanate-(FITC)-conjugated goat anti-guinea-pig (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at a dilution of 1:1000). DAPI (4′6′ diamidino 2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) was used as a co-strain to visualise DNA. Other antibodies used to investigate nuclear localisation were anti-Sla2p, Abp1p, Cof1p and Sac6p (given by D. Drubin, UC Berkeley, USA). It should be noted that in double staining of Sla1-myc and actin with rhodamine phalloidin (figure 1) the methanol/acetone treatment required to visualise Sla1p does not preserve the actin cable staining that would normally be seen when using formaldehyde fixation alone. For visualisation of GFP in strains expressing the NPF-Sso1-GFP construct, cells were grown on selective media overnight, then re-inoculated and grown for 3-4 hours at 30°C until cells were in log phase. 4μl cells were then placed on a slide and observed. Cells were viewed with an Olympus BX-60 fluorescence microscope with a 100 W mercury lamp and an Olympus100X Plan-NeoFluar oil-immersion objective. Images were captured using a Roper Scientific MicroMax 1401E cooled CCD camera using Scanalytics IP lab software on an Apple Macintosh 7300 computer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Liz Smythe and Ewald Hettema for critical reading of the manuscript; Pam Silver (Harvard Medical School); Paul Ko-Ferrigno (University of Cambridge, UK); Michael Rosbash (Brandeis University) and Mike Stark (University of Dundee) for providing yeast strains; David Drubin (U.C. Berkeley) for antibodies; and Hugh Pelham (MRC LMB, Cambridge) and Kelly Tatchell (Louisiana) for plasmids. FG was funded as a post-graduate student of the BBSRC and KRA is a senior non-clinical fellow of the Medical Research Council (G117/394).

Abbreviations

- NLS

nuclear localisation sequence

- NES

nuclear export sequence

References

- 1.Gourlay CW, Dewar H, Warren DT, Costa R, Satish N, Ayscough KR. An interaction between Sla1p and Sla2p plays a role in regulating actin dynamics and endocytosis in budding yeast. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2551–2564. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry KR, D’Hondt K, Chang JS, Newpher T, Huang K, Hudson RT, et al. Scd5p and clathrin function are important for cortical actin organization, endocytosis, and localization of Sla2p in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2607–2625. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard JP, Hutton JL, Olson JM, Payne GS. Sla1p serves as the targeting signal recognition factor for NPFX(1,2)D-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:315–326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodal AA, Manning AL, Goode BL, Drubin DG. Negative regulation of yeast WASp by two SH3 domain-containing proteins. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang HY, Xu J, Cai MJ. Pan1p, End3p, and Sla1p, three yeast proteins required for normal cortical actin cytoskeleton organization, associate with each other and play essential roles in cell wall morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:12–25. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.12-25.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren DT, Andrews PD, Gourlay CG, Ayscough KR. Sla1p couples the yeast endocytic machinery to proteins regulating actin dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1703–1715. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benmerah A. Endocytosis: Signaling from endocytic membranes to the nucleus. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R314–R316. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coda L, Salcini A, Confalonieri S, Pelicci G, Sorkina T, Sorkin A, et al. Eps15R is a tyrosine kinase substrate with characteristics of a docking protein possibly involved in coated pits-mediated internalization. J BIol Chem. 1998;273:3003–3012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vecchi M, Polo S, Poupon V, van de Loo JW, Benmerah A, Di Fiore PP. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of endocytic proteins. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1511–1517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyman J, Chen H, Di Fiore PP, De Camilli P, Brunger AT. Epsin 1 undergoes nucleocytosolic shuttling and its Eps15 interactor NH2-terminal homology (ENTH) domain, structurally similar to armadillo and HEAT repeats, interacts with the transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia Zn2+ finger protein (PLZF) J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:537–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrens J, vonKries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, et al. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoh K, Brott BK, Bae GU, Ratcliffe MJ, SY S. Nuclear localization is required for Dishevelled function in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol. 2005;4:3. doi: 10.1186/jbiol20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JS, Henry K, Geli MI, Lemmon SK. Cortical recruitment and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Scd5p, a protein phosphatase-1-targeting protein involved in actin organization and endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:251–262. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG. Actin assembly and Endocytosis: from Yeast to Mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:287–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.093127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayscough KR. Endocytosis and the development of cell polarity in yeast requires a dynamic F-actin cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1587–1590. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayscough KR. Endocytosis: Actin in the driving seat. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R124–R126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaksonen M, Sun Y, Drubin DG. A Pathway for Association of Receptors, Adaptors, and Actin during Endocytic Internalization. Cell. 2003;115:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. A modular design for the clathrin- and actin-mediated endocytosis machinery. Cell. 2005;123:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeb JDJ, Schlenstedt G, Pellman D, Kornitzer D, Silver PA, Fink GR. The Yeast Nuclear Import Receptor Is Required For Mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7647–7651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seedorf M, Silver PA. Importin/karyopherin protein family members required for mRNA export from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8590–8595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brune C, Munchel SE, Fischer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Weis K. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and functions in mRNA export. RNA-Publ RNA Soc. 2005;11:517–531. doi: 10.1261/rna.7291205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen TH, Neville M, Rain JC, McCarthy T, Legrain P, Rosbash M. Identification of novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins with nuclear export activity: Cell cycle-regulated transcription factor Ace2p shows cell cycle-independent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8047–8058. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8047-8058.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stade K, Ford C, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas F, Kutay U. Biogenesis and nuclear export of ribosomal subunits in higher eukaryotes depend on the CRM1 export pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2409–2419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stage-Zimmermann T, Schmidt U, Silver PA. Factors affecting nuclear export of the 60S ribosomal subunit in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:3777–3789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valdez-Taubas J, Pelham HRB. Slow diffusion of proteins in the yeast plasma membrane allows polarity to be maintained by endocytic cycling. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1636–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welch M, Drubin DG. A nuclear protein with sequence similarity to proteins implicated in human acute leukaemias is important for cellular morphogenesis and actin cytoskeletal function in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:617–632. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayscough KR, Eby JJ, Lila T, Dewar H, Kozminski KG, Drubin DG. Sla1p is a functionally modular component of the yeast cortical actin cytoskeleton required for correct localization of both Rho1p-GTPase and Sla2p, a protein with talin homology. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:1061–1075. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gourlay CW, Ayscough KR. Identification of an upstream regulatory pathway controlling actin-mediated apoptosis in yeast. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2119–2132. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu JL, Song WJ, Carlson M. Protein phosphatase type 1 interacts with proteins required for meiosis and other cellular processes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4199–4206. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venturi GM, Bloecher A, Williams-Hart T, Tatchell K. Genetic interactions between GLC7, PPZ1 and PPZ2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;155:69–83. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloecher A, Tatchell K. Dynamic localization of protein phosphatase type 1 in the mitotic cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:125–140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knaus M, Cameroni E, Pedruzzi I, Tatchell K, De Virgilio C, Peter M. The Bud14p-Glc7p complex functions as a cortical regulator of dynein in budding yeast. EMBO J. 2005;24:3000–3011. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang JS, Henry K, Wolf BL, Geli M, Lemmon SK. Protein phosphatase-1 binding to Scd5p is important for regulation of actin organization and endocytosis in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48002–48008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu XL, Tatchell K. Mutations in yeast protein phosphatase type 1 that affect targeting subunit binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7410–7420. doi: 10.1021/bi002796k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang B, Zeng GS, Ng AYJ, Cai MJ. Identification of novel recognition motifs and regulatory targets for the yeast actin-regulating kinase Prk1p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4871–4884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng GH, Yu XW, Cai MJ. Regulation of yeast actin cytoskeleton-regulatory complex Pan1p/Sla1p/End3p by serine/threonine kinase Prk1p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3759–3772. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heddad A, Brameier M, MacCallum RM. Evolving regular expression-based sequence classifiers for protein nuclear localisation. Apps. Evol. Comput. 2004:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benmerah A, Scott M, Poupon V, Marullo S. Nuclear functions for plasma membrane-associated proteins? Traffic. 2003;4:503–511. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42.James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dulic V, Egerton M, Elgundi I, Raths S, Singer B, Riezman H. Yeast Endocytosis Assays. Meths Enzymol. 1991;194:697–710. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94051-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagan IM, Ayscough KR. Fluorescence Microscopy in Yeast. In: Allan VJ, editor. Protein Localization by Fluorescence Microscopy: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayscough KR, Drubin DG. Immunofluorescence Microscopy of Yeast Cells. In: Celis J, editor. Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook. Academic Press; 1998. pp. 477–85. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koepp DM, Wong DH, Corbett AH, Silver PA. Dynamic localization nuclear import receptor and its interactions with transport factors. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:1163–1176. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neville M, Rosbash M. The NES-Crm1p export pathway is not a major mRNA export route in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1999;18:3746–3756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]