Abstract

Prodrugs of (-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-1,3-dioxolane-2,6-diamino purine (DAPD), organic salts of DAPD, 5′-l-valyl DAPD and N-1 substituted (-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-1,3-dioxolane guanosine (DXG) have been synthesized with the objective of finding molecules which might be superior to DAPD and DXG in solubility as well as pharmacologic profiles. Synthesized prodrugs were evaluated for anti-HIV activity against HIV-1LAI in primary human lymphocytes (PBM cells) as well as their cytotoxicity in PBM, CEM and Vero cells. DAPD prodrugs, modified at the C6 position of the purine ring, demonstrated several folds of enhanced anti-HIV activity in comparison to the parent compound DAPD without increasing the toxicity. The presence of alkyl amino groups at the C6 position of the purine ring increased the antiviral potency several folds, and the most potent compound (-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-1,3-dioxolane-2-amino-6-aminoethyl purine (8) was 17 times more potent than that of DAPD. 5′-l-Valyl DAPD 20 and organic acid salts 21-24 also exhibited enhanced anti-HIV activity in comparison to DAPD, while DXG prodrugs 16-17 exhibited lower potency than that of DXG or DAPD.

Keywords: Nucleoside; Prodrug; Dioxolane-guanine; Dioxolane-2,6-diaminopurine; DAPD; Amdoxovir; Anti-HIV activity

1. Introduction

Despite the effectiveness of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (De Clercq, 2001) in combination with a protease inhibitors (PI) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), a long-term use of these drugs result in the selection of viral resistance mutants (Turner et al., 2004). Furthermore, individuals, who have become recently infected with resistant strains of HIV-1, have significantly been increased (Mocroft et al., 2002; Tamalet et al., 2003; Little et al., 2002). Thus, the identification of novel anti-HIV agents with antiviral activity against drug-resistant strains of HIV-1 is critical.

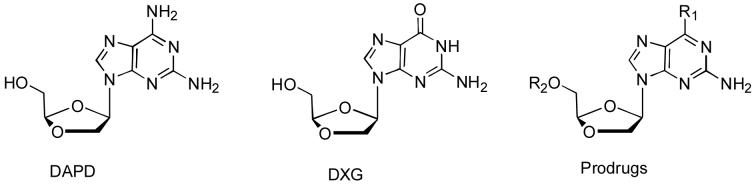

For past years, we have been interested in dioxolane nucleosides as potential anti-HIV agents (Chu et al., 1991; Kim et. al., 1992; Kim et. al., 1993; Furman, et al., 2001; Chu, et al., 2005; Liang, et. al., 2006), which possess a dioxolane ring in place of a classical carbohydrate moiety in nucleosides. The dioxolane nucleosides, such as (-)-β-D-(2R,4R) 1,3-dioxolane 2,6-diamino purine (DAPD) and (-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-dioxolane-tymine (DOT), are interesting in that they demonstrated interesting anti-HIV activity against drug resistant mutants (Chong et al., 2002; Chong et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005) (Figure 1). DAPD (amdoxovir), a reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), is deaminated in vitro as well as in vivo, yields a metabolite, (-)-β-D-1,3-dioxolane guanosine (Gu et al., 1999). Both DAPD and DXG demonstrated potent in vitro anti-HIV activity against wild type as well drug resistant strains (such as AZT, 3TC and abacavir) (Furman et al., 2001). Preliminary in vitro studies of dioxolane nucleosides shown that the lack of cross-resistance to AZT and the reversal of AZT resistance by DXG resistance mutations provide strong rationales for the use of these compounds in combination with other agents (Bazmi et al., 2000; Gallant et al., 2003; Walmsley et al., 2003). In order to understand the mechanism of this antiviral activity, we have conducted molecular modeling studies, which revealed that the 1,3-dioxolane moiety plays a significant role in stabilizing the binding between the mutant HIV-1 RT and the nucleoside triphosphate (Chong et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

DAPD has been undergoing clinical trials as an anti-HIV agent against drug resistant patients. Although the time of exposure of patients to DAPD was relatively short during the Phase I trials, the profile of adverse effects of the drug was favorable (Gu et al., 1999; Margolis et. al., 2006,). In addition, DAPD exhibited a favorable resistant profile in patients in that there were no genetic changes in the HIV reverse transcriptase coding regions, observed between the pretreatment and post treatment HIV genotypes within 15 days of DAPD monotherapy (Deeks et al., 2000). In the Phase IIa clinical trials (ACTG-5165) of amdoxovir (Margolis et al., 2006), highly treatment-experienced individuals failing existing antiretroviral therapy were treated. In a 96-week trial conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), amdoxovir 500 mg bid or amdoxovir 500 mg bid with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 500 mg bid, were administrated in addition to patients’ current failing treatment regimens. Amdoxovir was effective in subjects with viral strains resistant to nucleosides, including those harboring multiple thymidine analog mutations (TAMS) such as M41L and L210W mutations, as well as the M184V mutation selected by Epivir and Emtriva.

Despite of these positive profiles, optimum anti-HIV activity of DAPD has not been achieved due to its low oral bioavailability (approximately 30% in monkeys and rats) due to its low solubility in water (Chen et al., 1999). It is critical that anti-HIV agents also penetrate to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and suppress the HIV replication in order to alleviate the CNS dysfunction. The objective of the current study is to prepare DAPD/DXG prodrugs and evaluate their anti-HIV activity in vitro, which may provide the better pharmacokinetic profiles. Accordingly, we have designed and synthesized a series of lipophilic and water-soluble prodrugs of DAPD/DXG, and evaluated for their anti-HIV activity in vitro in order to select potential candidates for additional biological evaluations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemistry

All chemicals were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Company. Melting points were determined on a MEL1-TEMPII apparatus and were uncorrected. TLC was performed on Uniplate (silica gel) purchased from Analtech Co. Column chromatograph was performed using either silica gel-60 (220-240 mesh) for flash chromatography or silica gel G (TLC grade, >440 mesh) for vacuum flash column chromatography. NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Inova 500 spectrometer at 500 MHz with software VNMRC6-1 with Me4Si as the internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported as s (single), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet, or b (broad). UV spectra were recorded on a Beckman DU-650 spectrophotometer. Optical rotations were measured on a Jasco DIP-370 digital polarimeter. Mass spectra were measured on a Micromass Autospec mass spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Micro lab, Inc. (Norcross, GA). Five milligram (5 mg) of the compound was dissolved in minimum amount of water with sonication to calculate the solubility of compound in 1 mL of water.

Experimental procedure

Isobutyricacid-4-acetoxy-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (2)

To a well stirred solution of isobutyricacid-4-oxo-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (1) (51.5 g, 271.7 mmol) in dry THF (600 mL) at -78 °C, LiAl(OBut)3H (330 mL, 329.6 mmol, 1M solution in THF) was slowly added over a period of 1h under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 2 h at -78 °C and for additional 2 h at -10 °C. To this solution DMAP (41.4 g, 339.5 mmol) was added in one portion and stirred for 30 min followed by drop wise addition of Ac2O (141 mL, 1359 mmol). After stirring the bright yellow solution for 2 h at -10 °C, the temperature of the cold bath was allowed to rise to room temperature and stirred for overnight. The dark brown solution was pored into saturated NH4Cl (300 mL) solution, stirred for 30 min, filtered (to remove Li salt), concentrated and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 200 mL). The combined organic solutions were washed with saturated NaHCO3 (300 mL), brine and dried over Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford a crude product (red syrup). The crude product was purified by using column chromatography (ethyl acetate: hexanes 1:10-1:4) to afford isobutyricacid-4-acetoxy-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (2) (44.14 g, 70%) as yellow syrup. Rf: 0.45 (ethyl acetate: hexanes 1:4). NMR showed 1:1 mixture of α,β isomers. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.18 and 1.19 (2s, 6H, 2 × CH3); 2.10 (s, 3H, CH3); 4.20-4.42 (m, 4H, 2CH2); 5.38 and 5.42 (2d, 1H, CH); 5.82 (t, 1H, CH) 5.42; 6.41 and 6.35 (2d, 1H, CH),

Isobutyricacid-4-(R)-(2-amino-6-chloropurin-9-yl)-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (4a)

Isobutyricacid-4-acetoxy-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (2) (40 g, 172.3 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (600 mL) and cooled to -20 °C. Iodotrimethylsilane (41.37 g, 206.8 mmol) was slowly added to this pre-chilled solution by syringe over a period of 1.5 h and stirred for 2 h at -20 °C. To this solution was added per silylated 2-amino-6-chloropurine, dissolved in CHCl3 (600 mL) and stirred at -20 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature, stirred overnight and heated to gentle reflux. Reaction was monitored by TLC and after 4 h mixture was cooled, quenched with water, washed with saturated NaHCO3 (2 × 200 mL), saturated sodium thiosulfate solution (100 mL), water (2 × 200 mL), brine (2 × 200 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield a yellow solid of α,β-mixture of 4 (39 g, 66%). The crude product was further purified using vacuum silica gel column (hexane: ethyl acetate, 7:3- 3:7) to afford 4 as a 1:2, α:β mixture of anomers. TLC: Rf: 0.55 (ethyl acetate: hexane 7:3, α-anomer); Rf: 0.50 (ethyl acetate: hexane 7:3, β-anomer). β-Isomer (4a): 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.12 and 1.17 (2d, J=7.5 Hz, 6H, 2 × CH3); 2.59 (m, J = 7.5 Hz 1H, CH); 4.28 (m, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, CH2); 4.37 (m, 2H, CH2); 4.54 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 10.5 Hz, 1H, CH2); 5.17 (bs, 2H, NH2); 5.31 (t, J = 3.5, 1H, CH); 6.37 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, CH) and 8.12 (s, ArH). α-Isomer (4b): 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.20 and 1.21 (2s, 6H, 2 × CH3); 2.63 (m, 1H, J = 7.0 Hz CH); 4.18 and 4.20 (2d, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 4 Hz, 1H, CH2); 4.26 and 4.28 (2d, J = 3.5 Hz, J = 4 Hz, 1H, CH2); 4.48 (m, 2H, CH2); 5.17 (bs, 2H, NH2); 5.71 (t, J = 4, 1H, CH); 6.36 (dd, J = 5 Hz, J = 3 Hz, 1H, CH) and 7.89 (s, ArH)

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-6-chloro-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)purine (5)

A solution of 4a (1.0 g, 2.92 mmol) in MeOH (25 mL) was saturated with ammonia at 0 °C. Then the solution was allowed to stir for overnight at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified over flash silica gel chromatography (19:1, EtOAc: MeOH) to give 0.77 g (97%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/CH2Cl2: mp 192 °C (lit1 mp 193 °C). 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 3.83 (m); 4.30 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 9.5); 4.58 (d, J = 9.5); 5.16 (t, J = 2.5); 6.44 (d, J = 5.5); 8.08 (s, H-8) HRMS calcd C9H10N5O3Cl (MH+) 272.0550, found 272.0536.

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-6-azido-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)purine (6)

A solution of 5 (0.15 g, 0.55 mmol) and NaN3 (0.10 g, 1.66 mmol) in DMF (7 mL) was heated at 65 °C overnight. After cooling, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude compound was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH) to provide 0.14 g (91%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/H2O: mp 196 °C (decomposed); [α]25D = -68.67 (c 0.21, MeOH/H2O,1:1); UV (MeOH) λmax 271 nm (ε 8784), 300 nm (ε 10584); pH 7, 301 nm (ε 10698); pH 11, 301 nm (ε 9727); pH 2 303 nm (ε 1657); 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 3.84 (m); 4.35 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.5); 4.61 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 10.5); 5.19 (t, J = 2.5); 6.56 (dd, J = 1.0, J = 5.5); 8.02 (s, H-8) Anal. calcd for C9H10N8O3; C 38.85; H 3.62; N 40.27; found: C 38.92; H 3.68; N 40.03

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-methylaminopurine (7)

A solution of 5 (0.10 g, 0.37 mmol) and methylamine (40% solution in H2O, 5 mL) in MeOH (5 mL) was heated at 85 °C in a steel bomb for 5 h. After cooling the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude compound was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2: MeOH) to give 0.095 g (96%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/Pentane: mp 181-182 °C. [α]27D = -42.08 (c 0.25, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 281 nm (ε 18454); pH 7, 279 nm (ε 12266); pH 11, 279 nm (ε 11347); pH 2 259 nm (ε 14103); 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 3.06 (br s, N-CH3); 3.82 (m); 4.28 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.0); 4.49 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 10.0); 5.15 (t, J = 2.5); 6.32 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 5.5); 8.05 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C10H14N6O3 (MH+) 267.1205, found 267.1180. Anal. calcd for C10H14N6O3; C 45.11; H 5.30; N 31.56; found: C 44.84; H 5.35; N 31.46

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-ethylaminopurine (8)

Compound 5 (0.507 g 1.87 mmol), ethyl amine (2 mL) in MeOH (10 mL) was heated at 80 °C in a steel bomb for 16 h in an oil bath. The reaction mixture was cooled concentrated purified over silica gel column using ethyl acetate: MeOH, 98:2 to yield 0.44g (84%) of the title compound. mp 159-160 °C; [α]26D -31.75 (c 0.53, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 282 nm (ε 11440); pH 7, 281 nm (ε 11767); pH 11, 280 nm (ε 12185); pH 2, 291 nm (ε 10018);1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 1.29 (t, J = 7.0, CH3); 3.58 (br s, NH-CH2); 3.81 (m); 4.29 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.5); 4.48 (d, J = 10.0); 5.15 (t, J = 2.5); 6.32 (d, J = 5.0); 8.06 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C11H16N6O3 (MH+) 281.1362, found 281.1360, Anal. calcd for C11H16N6O3: C 47.14; H 5.75; N 29.98; found: C 46.84; H 5.62; N 29.78

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-6-dimethylamino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)purine (9)

A solution of 5 (0.10 g, 0.37 mmol) and dimethylamine (40% solution in H2O, 4 mL) in MeOH (6 mL) was heated at 85 °C in a steel bomb for 5h. After cooling the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude compound was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH) to give 0.095 g (92%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/Pentane: mp 119-121 °C; [α]27D = -44.16 (c 0.14, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 284 nm (ε 12068); pH 7, 284 nm (ε 11207); pH 11, 284 nm (ε 12084); pH 2 295 (ε 12661); 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 3.42 (br s, N-(CH3)2); 8.02 (s, H-8) 3.81 (m); 4.28 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 9.5); 4.81 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 9.5); 5.15 (t, J = 2.5); 6.33 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 5.5); HRMS calcd C11H16N6O3 (MH+) 281.1362, found 281.1360. Anal. calcd for C11H16N6O3·0.5H2O; C 45.67; H 5.92; N 29.05; found: C 46.00; H 5.88; N 28.81

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-isopropylaminopurine (10)

Compound 10 was prepared from compound 5 following the procedure given for the compound 8. Yield: 81%. mp 103-104 °C; [α]27D -31.48 (c 0.44, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 282 nm (ε 16389); pH 7, 281 nm (ε 15967); pH 11, 282 nm (ε 16180); pH 2, 293 nm (ε 13239); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.56, 1.40 (2s, (CH3)2); 2.21 (m), 2.09 (m), 1.62 (m); 3.57 (m); 4.15 (dd, J = 5.2, J = 14.8); 4. 38 (br s, N-CH); 4.40 (dd, J = 1.6, J = 14.8); 5.00 (t, J = 3.2); 5.14 (t, J = 7.0. OH); 5.84 (br s, NH2); 6.23 (d, J = 4.0); 6.97 (br s, NH); 7.83 (s, H-8). HRMS calcd C12H18N6O3 (MH+) 295.1518, found 295.1517, Anal. calcd for C12H18N6O3.0.4H2O: C 47.80; H 6.28; N 27.87; found: C 47.56; H 6.24; N 27.63

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-methoxypurine (11)

To a stirring solution of 5 (0.10 g, 0.37 mmol) in MeOH (7 mL), NaOMe (0.5 M soln. in MeOH, 2 mL) was added and allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. After cooling the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude compound was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, EtOAc:MeOH) to give 0.09 g (91%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/CH2Cl2/Pentane: mp 196 °C; [α]27D = -44.88 (c 0.5, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 248 nm (ε 9276), 281 nm (ε 8605); pH 7, 279 nm (ε 8444); pH 11, 279 nm (ε 8645); pH 2 288 nm (ε 5865); 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 3.81 (m); 4.07 (s, O-CH3), 8.19 (s, H-8); 4.29 (dd, J = 5.0, J = 10.0); 4.51 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 10.0); 5.15 (t, J = 2.5); 6.39 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 5.0); HRMS calcd C10H13N5O4 (MH+) 268.1046, found 268.1091. Anal. calcd for C10H13N5O4 ·0.25H2O; C 44.20; H 5.00; N 25.77; found: C 44.46; H 5.01; N 25.66

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-6-cyclopropylamino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)purine (12)

A solution of 5 (0.10 g, 0.37 mmol) and cyclopropylamine (3 mL) in MeOH (7 mL) was heated at 65 °C in a steel bomb for 5 h. After cooling the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the crude compound was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH) to give 0.10 g (92%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/Pentane: mp 86 °C (decomposed); [α]23D = -34.50 (c 0.27, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 284 nm (ε 11700); pH 7, 283 nm (ε 11972); pH 11, 283 nm (ε 12664); pH 2 296 nm (ε 13885); 1H NMR (MeOH-d4): δ 0.63 (m, CH2), 0.86 (m, CH2), 2.94 (br s, N-CH); 3.81 (m); 4.28 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.0); 4.48 (d, J = 10.0); 5.15 (t, J = 2.5); 6.33 (d, J = 5.5); 8.07 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C12H16N6O3 (MH+) 293.1292, found 293.1218. Anal. calcd for C12H16N6O3·0.5H2O; C 47.84; H 5.68; N 27.89; found: C 48.21; H 5.53; N 27.61

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-cyclobutylaminopurine (13)

Compound 13 was prepared from compound 5 following the procedure given for the compound 8. Yield: 84%. mp 170-171 °C; [α]27D -30.85. deg (c 0.71, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 284 nm (ε 9987); pH 7, 283 nm (ε 10562); pH 11, 283 nm (ε 10118); pH 2, 294 nm (ε 8656); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.60 (m); 4.20 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 15.0); 4.43 (d, J = 8.0); 4. 68 (br s,_N-CH); 5.04 (t, J = 3.0); 5.18 (t, J = 6.0. OH); 5.91 (br s, NH2); 6.22 (d, J = 4.5); 7.56 (br s, NH); 7.88 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C13H18N6O3 (MH+) 307.1518 found 307.1518, Anal. calcd for C13H18N6O3: C 50.97; H 5.92; N 27.44; found: C 50.78; H 5.82; N 27.26

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-Amino-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-6-benzylaminopurine (14)

Compound 10 was prepared from compound 5 following the procedure given for the compound 8. Yield: 90%. mp 160-161 °C; [α]26D -42.18 (c 0.112, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 283 nm (ε 11819); pH 7, 281 nm (ε 11711); pH 11, 282 nm (ε 11502); pH 2, 286 nm (ε 9790); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.60 (dd, J = 3.0, J = 8.5); 4.20 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.0); 4.45 (d, J = 10.0); 4.65 (br s, N-CH); 4.65 (br s, NH-CH2); 5.04 (t, J = 3.0); 5.17 (t, J = 7.0. OH); 5.94 (br s, NH2); 6.23 (d, J = 5.0); 7.20- 7.35 (m, 5ArH); 7.89 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C16H18N6O3 (MH+) 343.1518, found 343.1508, Anal. calcd for C16H18N6O3: C 56.13; H 5.30; N 24.55; found: C 56.12; H 5.34; N 24.17

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-9-(2-Hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)guanosine (15)

A solution of 4a (1.0 g, 2.92 mmol), mercaptoethanol (2.75 g, 35.25 mmol) and NaOMe (25% wt. soln., 9.5 mL) in MeOH (30 mL) was heated at reflux for 3.5 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and neutralized to pH 7.0 with acetic acid. The solution was evaporated to dryness and the solid obtained was washed with CHCl3 followed by MeOH to give 0.6 g (81%) of the title compound as a white solid: mp 280 °C (decomposed) (lit1 mp 280 °C); UV (H2O) λmax 250 nm; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.56 (dd, J = 3.2, J = 5.6); 4.15 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 9.5); 4.40 (d, J = 9.5); 4.99 (t, J = 3.2); 5.11 (t, J = 5.6); 6.12 (d, J = 5.5); 6.54 (br s, NH2), 7.81 (s, H-8), 10.71 (br s, NH).

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-9-(2-Hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)-N1-methylguanosine (16)

The title compound was synthesized according to a similar literature procedure (Badet et al., 1984). A solution of 15 (0.10 g, 0.39 mmol) and KOH (33 mg, 0.59 mmol) (dissolved in H2O(0.2 mL) and DMF (2 mL) in DMF (10 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Diphenylmethylsulfoniumtetrafluoroborate (0.11 g, 0.39 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was slowly added to the reaction mixture and allowed to stir for an additional 2 h. The solution was evaporated to dryness and the solid obtained was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH) to give 0.08 g (77%) of the title compound which was recrystallized from MeOH/pentane: mp 210-212 °C; [α]27D = -49.18 (c 0.21, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax255 nm (ε 3535); pH 7, 255 nm (ε 12841); pH 11, 254 nm (ε 15212); pH 2 258 nm (ε 12091); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.57(s, N-CH3), 5.14 (t, J = 5.6); 3.60 (dd, J = 3.2, J = 5.6); 4.20 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.0); 4.46 (dd, J = 1.5, J =10.0); 5.04 (t, J = 3.2); 6.17 (dd, J = 1.5, J = 5.5); 7.10 (br s, NH2), 7.87 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C10H13N5O4 (MH+) 268.1046, found 268.0938. Anal. calcd for C10H13N5O4·0.5H2O; C 43.48; H 5.11; N 25.35; found: C 43.39; H 5.14; N 25.39

(-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-N1-Benzyl-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxalan-4-yl)guanosine (17)

A solution of 15 (0.11 g, 0.44 mmol) and NaH (13 mg, 0.53 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min followed by 20 min stirring at room temperature. Then benzyl bromide (0.075 g, 0.44 mmol) was slowly added to the reaction mixture at 0 °C and then continued stirring at room temperature for 2 h. The solution was evaporated to dryness and the solid obtained was purified over flash chromatography silica gel (19:1, CH2Cl2:MeOH) to give 0.10 g (66%) of the title compound as a white solid which was recrystallized from MeOH/pentane: mp 168-170 °C; [α]26D = -38.18 (c 0.21, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 257 nm (ε 3733); pH 7, 255 nm (ε 12114); pH 11, 254 nm (ε 13048); pH 2 261 nm (ε 39467); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 3.62 (dd, J = 3.5, J = 6.0); 4.20 (dd, J = 5.5, J = 10.0); 4.59 (dd, J = 1.5, J =10.0); 5.05 (t, J = 3.5); 5.14 (t, J = 6.0); 5.26 (br s, CH2-benzylic); 6.18 (d, dd, J = 1.5, J = 5.5); 7.09 (br s, NH2),7.20 (d, J = 7.0, 2Ar-H); 7.26 (dd, J = 7.0, J = 7.5, Ar-H); 7.33 (dd, J = 7.0, J = 7.5, 2-Ar-H); 7.91 (s, H-8); HRMS calcd C16H17N5O4 (MH-) 342.1203, found 342.1256. Anal. calcd for C16H17N5O4·0.5H2O; C 54.54; H 5.14; N 19.88; found: C 54.61; H 5.11; N 19.82

2-tert-Butoxycarbonylamino-3-methyl-butyric acid 4-(2,6-diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-ylmethylester (18)

Boc-l-valine (8.61 g, 0.039 mol) and dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (4.1 g, 0.039 mol) were taken in DMF (250 mL) and stirred at room temperature under nitrogen for 1 h. Reaction mixture was cooled to 0 -5°C. Pre-cooled solution (0 -5 °C) of DAPD (5 g, 0.0198 mol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (2.41 g, 0.0396 mol) dissolved in DMF (750 mL) was slowly added into the reaction mixture. Reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h at 0-5 °C and further stirred at room temperature for overnight. Reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and crude product was stirred with 500 mL of water at 0 -5 °C for 2 h. Solid residue was filtered and washed with water (200 mL) and dichloromethane (200 mL). Aqueous portion was further extracted with 3 ×100 mL of dichloromethane. Organic layers were combined, washed with sat. NaHCO3, brine and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, concentrated to provide the crude product and further purified by column chromatography using ethyl acetate and methanol to yield 4 g (45%) of pure white solid.1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 0.86-89 (m, 6H, valyl-2CH3), 1.40(s, 9H, 3CH3), 1.97-2.01 (m, 1H, valyl-3″ CH), 3.87 (m, 1H, valyl-2″ CH), 4.25-4.31 (m, 3H, 2′ CH and 5′-CH2), 4.56-4.59 (m, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.26-5.27 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H, 4′ CH), 5.88 (br s, 2H, NH2), 6.25-6.26 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.78 (br s, 2H, NH2), 7.18-7.20 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.83 (s, 1H, CH-purine).

2-Amino-3-methyl-butyric acid 4-(2,6-diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-ylmethylester. TFA salt (Valyl DAPD-TFA salt) (19)

Boc-Val-DAPD (18) (8.5 g, 0.019 mol) was dissolved in 200 mL dichloromethane and cooled to 0-5 °C. Trifluroacetic acid (15 mL) was slowly added in portions (3 × 5 mL) with stirring at 0-5 °C for 3 h. Reaction mixture was further stirred at room temperature of 3 h and monitored by TLC, and after completion, reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. Ether (100 mL) was added into the concentrated residue to get precipitate. White solid obtained was filtered and washed with ether (25 mL) and crystallized with methanol/DCM (1:4) to provide 7.0 g (53.0%) of the title compound. mp 178-180 °C; [α]26D = -22.96 (c 0.54, MeOH); 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 0.95-1.00 (dd, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H, valyl-2CH3), 2.12-2.18 (m, 1H, valyl-3″ CH), 3.82 (bs, 1H, valyl-2″ CH), 4.31-4.34 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 4.46-4.47 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H, 5′-CH2), 4.69-4.72 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.35-5.37 (t, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H, 4′ CH), 6.27-6.28 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 7.25 (br s, 2H, NH2), 8.08 (s, 1H, CH-purine), 8.40 (br s, 4H, 2NH2).

2-Amino-3-methyl-butyric acid 4-(2,6-diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-ylmethylester) (20)

Trifluroacetic acid salt 3.5 g (5.04 mmol) (19) was dissolved in isopropanol (1.2 L). PL-HCO3 resin (9 g, washed with 500 mL of isopropanol) was added into the clear solution of trifluroacetic acid salt with stirring and further stirred for 1 h at room temperature. Free base (20) formation was achieved using PL-HCO3 resin and it was monitored by TLC. After completion of reaction, isopropanol was removed under reduced pressure at 30 °C. Residue was taken in DCM (200 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure to remove the traces of isopropanol. DCM (200 mL) was added into the residue and sonicated the reaction mass for 5-10 min. After sonication, 100 mL of pentane was added into the reaction mass and stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Separated white solid was filtered and washed with 100 mL of pentane to yield 1.5 g (85 %) of pure title compound. mp 77-80 °C; [α]26D = -38.00 (c 0.48, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 0.82-0.88 (dd, J = 6.5 Hz, J = 19 Hz, 6H, valyl-2CH3), 1.64 (bs, 2H, valyl-NH2), 1.79-1.83 (m, 1H, valyl-3″ CH), 3.10-3.11 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, valyl-2″ CH), 4.24-4.33 (m, 3H, 2′ CH, 5′-CH2), 4.58-4.60 (dd, J = 2.5 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.27-5.29 (t, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H, 4′ CH), 5.89 (bs, 2H, NH2), 6.23-6.25 (dd, J = 2.0 Hz, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.78 (bs, 2H, NH2), 7.82 (s, 1H, CH-purine); 13C-NMR (DMSO) δ: 17.84, 19.63, 32.32, 59.85, 62.93, 70.46, 79.16, 102.51, 113.21, 134.98, 152.03, 156.62, 160.94, 175.49.; Anal. (C14H21N7O4) C, 47.86; H, 6.02; N, 27.90. Found C, 47.91; H, 6.08; N, 27.95.

General procedure for the synthesis of DAPD organic salts

DAPD (0.2 g, 0.79 mmol) and organic acid (0.86 mmol) was stirred in 6 mL of water for 24 h. Reaction mixture was filtered and washed with 1 mL of water and then 20 mL of acetone. White solid obtained was dried under vacuum to provide title compound.

[4-(2,6-Diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-yl]-methanol maleate (DAPD-maleate) (21)

mp 161-163 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 3.63-3.64 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H, 5′-CH2), 4.20-4.24 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 4.49-4.51 (m, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.06-5.07 (t, 1H, J = 3.5 Hz, 4′ CH), 6.17 (s, 2H, maleate-CH), 6.22-6.23 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.73 (br s, 2H, NH2), 7.86 (bs, 2H, NH2), 8.08 (s, 1H, CH-purine); Anal. (C9H12N6O3·C4H4O4 H2O) C, 40.42; H, 4.70; N, 21.75, found C, 40.65; H, 4.77; N, 21.75

[4-(2,6-Diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-yl]-methanol tartarate (DAPD-tartarate) (22)

mp 212-214 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 3.61-3.62 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H, 5′-CH2), 4.19-4.22 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 4.33 (s, 1H, tartarate-CH), 4.44-4.47 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.05-5.06 (t, 1H, J = 3.5 Hz, 4′ CH), 5.22 (br s, 1H, 5′ OH), 5.89 (br s, 2H, NH2), 6.21-6.23 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.79 (bs, 2H, NH2), 7.89 (s, 1H, CH-purine); Anal. (C9H12N6O3·C4H6O6·C9H12N6O3) C, 40.37; H, 4.62; N, 25.68, found C, 40.50; H, 4.63; N, 25.74.

[4-(2,6-Diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-yl]-methanol citrate (DAPD-citrate) (23)

mp 168-170 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 2.66, 2.69 (2s, 2H, citrate-CH2), 2.76, 2.79 (2s, 2H, citrate-CH2), 3.62-3.63 (d, 2H, 5′-CH2), 4.19-4.22 (m, 1H, 2′ CH), 4.45-4.47 (m, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.05-5.06 (t, 1H, J = 3.0 Hz, 4′ CH), 5.24 (bs, 1H, 5′ OH), 5.96 (br s, 2H, NH2), 6.21-6.23 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.88 (br s, 2H, NH2), 7.91 (s, 1H, CH-purine); Anal. (C9H12N6O3·C6H8O7·C9H12N6O3) C, 41.38; H, 4.63; N, 24.13. found C, 41.32; H, 4.72; N, 24.19.

[4-(2,6-Diamino-purin-9-yl)-[1,3]dioxolan-2-yl]-methanol. fumarate (DAPD-fumarate) (24)

mp 212-214 °C; 1H-NMR (DMSO) δ: 3.58-3.59 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H, 5′-CH2), 4.16-4.19 (q, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 4.42-4.44 (dd, J = 1.5 Hz, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, 2′ CH), 5.02-5.03 (t, 1H, J = 3.0 Hz, 4′ CH), 5.86 (bs, 2H, NH2), 6.19-6.20 (m, 1H, 1′ CH), 6.63 (s, 1H, fumarate-CH), 6.76 (bs, 2H, NH2), 7.86 (s, 1H, CH-purine); Anal. (C9H12N6O3·C4H4O4 C9H12N6O3) C, 42.58; H, 4.55; N, 27.09. found C, 42.45; H, 4.65; N, 26.17

3.Virology

3.1. Antiviral assays

The procedures for the antiviral assays in human peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells have been published previously (Schinazi et al., 1990 and 1998). In summary, PBM cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque discontinuous gradient centrifugation of whole blood samples (obtained from Atlanta Red Cross) from healthy seronegative donors. Cells were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin A (3 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2-3 days prior to use. HIV-1LAI obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) was used as the standard reference virus for the antiviral assays. Infections were done in bulk for 1 h, either with 100 TCID50 / 1 × 107 cells for a flask (T25) assay or with 200 TCID50 / 2 × 106 cells/well for 24 well plate assay. Previous studies indicated that this was the optimum virus concentration in order to obtain good replication on day 5 when the virus is harvested from the supernatant. Cells were added to a flask or plate containing a 10-fold serial dilution of the test compound. Assay medium was RPMI-1640 supplemented with heat inactivated 16% fetal bovine serum, 1.6 mM 1-glutamine, 80 IU/mL penicillin, 80 μg /mL streptomycin, 0.0008% DEAE-Dextran, 0.045% sodium bicarbonate, and 26 IU/mL recombinant interleukin-2 (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA). AZT was used as the positive control for the assay. Uninfected PBM cells were grown in parallel at equivalent cell concentrations as a control. The cell cultures were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2-air at 37 °C for 5 day, and supernatants were collected for reverse transcriptase activity. 1 mL of each supernatant was centrifuged at 9,740 g for 2 h to pellet the virus. The pellet was solubilized with vortexing in 100 μL of virus solubilization buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.8 M NaCl, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl chloride, 20% glycerol, and 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.8). Each sample (10 μL) was added to 75 μL of RT reaction mixture (0.06 M Tris, pH 7.8, 0.012 M MgCl2, 0.006 M dithiothreitol, 0.006 mg/mL poly (rA)n oligo (dT)12-18, 96 μg/mL dATP, and 1 μM of 0.08 mCi/mL 3H-thymidine-5′-triphosphate) (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid containing 0.05% sodium perophosphate. The acid-insoluble product was harvested onto filter paper using a Packard Harvester (Meriden, CT), and RT activity was read on a Packard Direct Beta Counter (Meriden, CT). RT results were expressed in counts per minute (CPM) per milliliter. The antiviral 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 90% effective concentration (EC90) was determined from the concentration-response curve using the median effect method (Balazarini et al., 1994).

3.2.Cytotoxicity assays

The compounds were evaluated for their potential toxic effects on uninfected PHA-stimulated human PBM cell, CEM (T-lymphoblastoid cell line obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) and Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells. Log phase Vero, CEM and PHA-stimulated human PBM cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103, 2.5 × 103, and 5 × 104 cells/well, respectively. All of the cells were plated in 96-well cell culture plates containing 10-fold serial dilutions of the test drug. The cultures were incubated for 2, 3, and 4 days for Vero, CEM, and PBM cells, respectively, in a humidified 5% CO2-air at 37 °C. At the end of incubation, MTT tetrazolium dye solution (cell titer 96, Promega, Madison, WI) was added to each well and incubated overnight. The reaction was stopped with stop solubilization solution (Promega, Madison, WI). The plates were incubated for 5 h to ensure that the formazan crystals were dissolved. The plates were read at 570 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, Model EL 312e). The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) was determined from the concentration-response curve using the median effect method (Stuyver et al., 2002; Balzarini et al., 1994).

3.3 Adenosine Deaminase Study

All the enzyme reactions were performed at 37 °C in phosphate buffer solution (pH=7.4). Initially, adenosine deaminase (EC. 3.5.4.4) from calf intestinal mucosa from Sigma-Aldrich (20 μg/mL) was used for the qualitative assay with the substrate concentration of 1.5 mM, to determine whether the DXG is the sole product of hydrolytic deamination reaction of DAPD prodrugs (6-14). Adenosine deaminase from bovine spleen from Sigma-Aldrich (5.0 units/mL) was then used in the quantitative assays, which was monitored with a UV spectrometer at 285 nm with the substrate concentration of 100 μM. The change in absorbance (ΔAt = At - A0) at certain time (t) of each substrate was recorded and compared with the total change of absorbance (ADXG - Asubstrate) to calculate the percentage of substrate conversion in the enzyme reaction.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Chemistry

Antiviral activity of nucleosides depends on the cellular uptake as well as the conversion to the corresponding 5′-triphosphate by cellular kinases (Balzarini, 1994). However, their clinical utility is often hampered (Kennedy, 1997) by their unfavorable physiochemical properties. To alleviate these problems, prodrug approaches have been adopted to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs (Fleisher et al., 1996; Han and Amidon, 2000). Several clinically useful nucleoside drugs such as abacavir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, adefovir dipivoxil, valaciclovir and famciclovir are the products from these efforts.

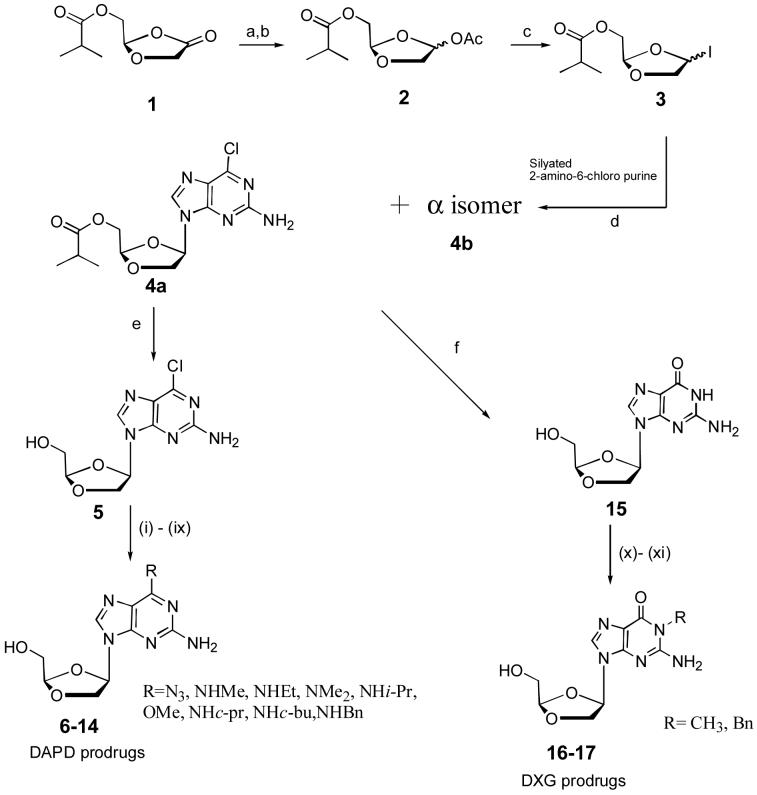

Abacavir is a prodrug of carbovir. A number of different C6-aminosubstituents have been explored to improve the oral bioavailability of carbovir, resulting in the discovery of the C6-cyclopropylamine prodrug, abacavir (Vince and Hua, 1990; Daluge et al., 1997). In view of the success of abacavir, we explored modifications of the C6-position of the purine ring of DAPD. Modifications at the C6-position of DAPD were achieved from the key intermediate (-)-β-D-(2R,4R)-2-amino-6-chloro-9-(2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl) purine (5), which was synthesized from isobutyricacid-4-oxo-[1,3]-dioxolan-2-(R)-yl methyl ester (1) in 4 steps as depicted in Scheme 1. Literature methods were modified and improved to synthesize the compound 4a. Compound 1 was reduced by LiAl(OBut)3H in THF at -78 °C, and acetylated in situ using acetic anhydride and 4-dimethylaminopyridine, and then purified by a silica gel column to obtain a α,β-mixture. The resulting α,β-mixture was treated with iodotrimethylsilane to provide the iodo compound 3. 2-Amino-6-chloro-purine was persilyated using 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) and an equivalent amount of ammonium sulfate to form the persilylated base. The compound 3 was then condensed with persilylated 2-amino-6-chloro purine at -20 °C in CHCl3 to provide an α,β-mixture (4a and 4b) in the ratio of 1:2 (66%). The reported method (Kim et al., 1993) gave a 1:1 ratio. The resulting anomeric mixture was separated by flash silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate-hexanes as the eluent. In this reaction, it is observed that kinetically controlled N7 isomers were converted into the thermodynamically controlled desired N9 product after stirring overnight at room temperature. After extensive investigation of this reaction, by employing several solvents, we optimized the reaction conditions and found chloroform to give the best results with an enhanced β isomer ratio (α:β = 1:2) in 66% yield. Another improvement we made in this reaction was the use of one equivalent of ammonium sulfate (Ye et al., 2004) instead of catalytic amounts to enhance the solubility of 2-amino-6-chloropurine. The key intermediate 5 was then reacted with various amines in steel bomb using methanol as the solvent to yield various prodrugs of DAPD as shown in the Scheme 1. To synthesize DXG prodrugs, compound 4a was converted into DXG (15) using mercaptoethanol and NaOMe in 81% yield, which was then treated with different reagents as shown in the Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of DAPD and DXG prodrugs.

Reagents and Conditions: (a) LiAl(OBut)3H, THF, -78 °C (b) DMAP, (CH3CO)2O, -20 °C (c) TMSI, CHCl3, -20 °C, 2 h, (d) (NH4)2SO4, -20 °C, 2 h, rt, 8 h, gentle reflux, 2 h (e) saturated methanolic ammonia, 0 °C, 2 h, room temperature, overnight (f) HOC2H4SH, NaOMe, MeOH, 3.5 h reflux, (i) NaN3, DMF (ii) methylamine 40% solution in H2O, MeOH (iii) ethylamine, MeOH (iv) dimethylamine 40% solution in H2O, MeOH (v) isopropylamine, MeOH (vi) NaOMe, MeOH (vii) cyclopropylamine, MeOH (vii) cyclobutylamine, MeOH (ix) benzylamine, MeOH (x) KOH, DMF, diphenylsulfoniumtetrafluoroborate (xi) NaH, C6H5CH2Br.

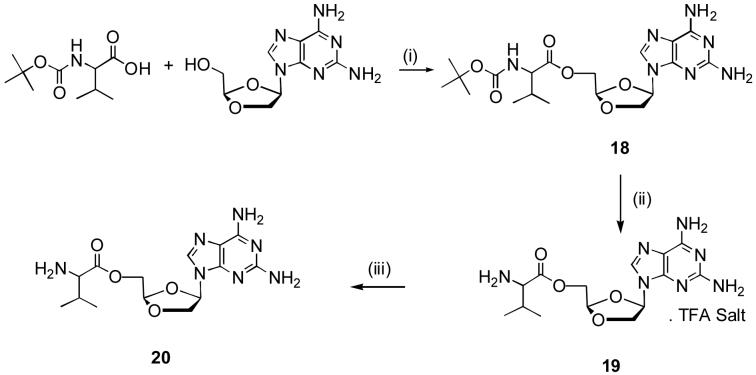

A number of nucleosides exhibit only modest oral bioavailability (Deeks et al., 2000). The oral bioavailability can be improved by modification of the free hydroxyl group. (Chulay et al., 1999; Lalezari et al., 2002). Amino acids substitution may be suitable for this modification without compromising for the water solubility of a compound. l-Valine was proved to be a good choice for the synthesis of several prodrugs (Benzaria et al., 2003; Ghosh and Miller et al., 1995; Song et al., 2005). Therefore, l-valine was used to synthesize 5′-valyl-DAPD to improve its anti-HIV activity. Boc-l-val-DAPD 18 was synthesized by the reaction of Boc-l-val with DAPD in the presence of 4-dimethylaminopyridine and dicyclohexylcabodiimide in DMF. Deprotection of Boc-l-valine with trifluroacetic acid at 0 °C in dichloromethane resulted in trifluroacetic acid salt 19. Free 5′-l-valyl-DAPD 20 was obtained by treating 19 with PL-HCO3 resin.

Initial attempts to isolate pure free base 20, after deprotection of the Boc-group by acidic conditions, were failed which may be attributed to the presence of three free amino groups, leading to hydrolysis of the 5′-l-valyl ester during its chromatographic purification using 10% methanol in the mobile phase. This fact was also supported by NMR and optical rotational analysis, which showed that the compound 20 has a half-life less than 6 h in methanol and water. The trifluroacetic acid salt 19 was prepared by using an excess of trifluroacetic acid in dry dichloromethane and isolated as a pure white solid. A pure freebase 20 was obtained as a white powder by treating 19 with quaternary amine-HCO3 resin (PL-HCO3 SAX-resin) in isopropanol. The compound 20 was highly soluble in water and was stable at room temperature under closed conditions. However, it decomposed in a mixture of water and methanol with time, which was monitored and confirmed by NMR, optical rotation as well as by TLC.

Changing the salt form of a drug is a recognized means of modifying its solubility without modifying its structure. Different salts of the same active drug are distinct products with their own chemical and biological profiles that may cause differences in their clinical efficacy and safety (Glynis, D., 2001). Subsequently, different organic acid salts 21-24 were prepared using maleic, tartaric, citric and fumaric acid, and they were evaluated for its anti-HIV activity.

4.2. Anti-HIV activity

Anti-HIV activity of the synthesized prodrugs of DAPD and DXG were evaluated against HIV-1LAI in peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells (Schinazi et al., 1990) and cytotoxicity in PBM, CEM and Vero cells, and the results are summarized in Table 1. Compounds 6-17 exhibited varying degrees of anti-HIV activity. As shown in Table 1, most of the synthesized compounds showed good anti-HIV activity without the enhancement of cytotoxicity. Compound 8, having an ethyl amino group at the C6 position, exhibited a 17-fold increased potency in comparison to the parent compound. Compound 12 with a cyclopropyl amino group also showed an 8-fold increase of anti-HIV activity compared to that of DAPD. Substituion of an azido or a methoxy group at C6 showed the similar potency as that of DAPD. The least potent compound in this series was the compound 14 having benzyl amino group at the C6 position. The descending order of anti-HIV activity of C6 substituted 1,3-dioxonyl-2-aminopurine in comparison to DAPD is as follows: ethylamino (17 times) > cyclopropylamino (8 times) > dimethylamino (8 times) > methylamino (5 times) > cyclobutylamino (4 times) > methoxy (2 times) isopropylamino (same as DAPD) azido (less than DAPD) > benzylamino (less than DAPD). From the preliminary in vitro studies, it can be concluded that, a small-size substitution with an electron donating group on the C6 position increases the anti-HIV activity (ethylamino EC50 0.41μM), whereas the bulky-substitutent at the same position reduces (benzyl EC50 44.90 μM) the biological activity, which may be related to hydrolysis by adenosine deaminase. This conclusion may be supported by the earlier work, a hydrolytic deamination of 2′-fluoro-2′,3′-dideoxyarabinofuranosyl-adenine nucleosides (Barchi et al., 1991) as well as by 2-amino-6-halo and 6-halo-2′,3′-dideoxy purine ribofuronosides by adenosine deaminase (Shirasaka et al., 1990). However, it was not the case in our studies (see below). All the synthesized organic acid salts of DAPD exhibited enhanced anti-HIV activity in comparison to DAPD without increasing the cytotoxicity, in which the DAPD tartarate salt exhibited a 10-fold activity in comparison to that of DAPD (Table 1). Similarly, 5′-L-valyl-DAPD (20) showed enhanced water solubility as well as anti-HIV activity in comparison to that of DAPD.

Table 1.

Anti-HIV activity & cytotoxicity of DAPD, DXG prodrugs and DAPD salts

| DAPD Prodrugs | Anti-HIV Activity (a) | Cytotoxicity IC50 (μM) in | Calc. LogP(b) | Solu. mg/mL (Water) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | R | EC50 (μM) | EC90 (μM) | PBM | CEM | VERO | |||

|

6 | N3 | 13.0 ± 8.30 | ≥70.0 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.169 | 1.33 |

| 7 | NHMe | 1.30 ± 0.071 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.748 | 3.10 | |

| 8 | NHEt | 0.41 ± 0.25 | 7.5 ± 4.6 | 99.5 | >100 | >100 | -0.219 | 1.64 | |

| 9 | NMe2 | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 3.6 ± 0.49 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.694 | 1.16 | |

| 10 | NHi-Pr | 5.40 ± 5.20 | ≥25.0 | 97.3 | >100 | >100 | 0.090 | 1.48 | |

| 11 | OMe | 3.80 ± 4.10 | 11.4 ± 12.6 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.680 | 3.08 | |

| 12 | NHc-pr | 0.85 ± 0.26 | 13.0 ± 14.1 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.394 | 2.09 | |

| 13 | NHc-bu | 2.20 ± 1.40 | 16.0 ± 15.7 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 0.165 | 1.74 | |

| 14 | NHBn | 44.90 ± 27.9 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 0.700 | 0.68 | |

| DAPD | NH2 | 6.90 ± 4.70 | 12.5 ± 26.3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -1.579 | 0.40 | |

|

16 | CH3 | 14.2 ± 4.70 | 47.3 ± 22.6 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -2.498 | 3.0 |

| 17 | Bn | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.730 | 1.0 | |

| DXG | 0.51 ± 0.44 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -2.634 | 0.1 | ||

| 20 l-5′-Val-DAPD | 1.7 ± 1.10 | 11.5 ± 2.0 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -0.370 | 70.0 | ||

| 21 DAPD Maleate mono salt | 2.2 ± 0.17 | 11.3 ± 1.3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -- | 3.0 | ||

| 22 DAPD Tartarate hemi salt | 0.7 ± 0.03 | 6.2 ± 4.6 | >97.3 | >100 | >100 | -- | 3.4 | ||

| 23 DAPD Citrate hemi salt | 1.6 ± 0.14 | 7.2 ± 3.0 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -- | 7.0 | ||

| 24 DAPD Fumarate hemi salt | 2.6 ± 2.00 | 6.1 ± 2.5 | >100 | >100 | >100 | -- | 3.8 | ||

| DAPD | 6.90 ± 4.70 | 12.5 ± 26.3 | >100 | >100 | -1.579 | 0.40 | |||

| AZT | 0.007±0.0047 | 0.04±0.02 | >100 | 14.3 | 50.6 | -- | -- | ||

in human PBM cells unless otherwise indica indicated. Based on three replicate assays

calculated from ChemDraw ultra 7.1 version

4.3. Lipophilicity, Solubility, Hydrolysis and Stability

Modification at the C6-position of the purine ring of DAPD with C6-alkyl amino groups instead of amino group expected to change the biochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds. It can increase the biochemical stability that may leads to potential improvement for intracellular transportation of the compounds. Accordingly, prodrugs of DAPD were synthesized with a series of lipophilic groups at the C6-position, and calculated the logP values of these compounds (Table 1) compared to that of DAPD. Table 1, indicates that compound 8 (logP -0.219; EC50 0.41μM) showed a 17-fold increase in anti-HIV activity in comparison to DAPD (logP 1.579; EC50 6.9 μM). Compound 12 (logP -0.394; EC50 0.85 μM) and compound 7 (logP -0.748; EC50 1.30 μM) exhibited a 8-fold enhancement in their anti-HIV activity compared to DAPD. If the calculated logP is positive, (compound 10 logP 0.09; EC50 5.4 μM, compound 13 logP 0.165; EC50 2.2 μM), they showed slightly reduced antiviral activity in comparison to DAPD. Solubility of the synthesized prodrugs were measured in water and observed that all the synthesized prodrugs were more soluble than that of DXG or DAPD, and the anti-HIV activity was, in general, increased with increase of solubility in water. Hydrolytic deamination of the prodrugs is very critical allowing the release of DXG into the intracellar compartment for phosphorylation. It has been documented that a numerous C6-substituted purine nucleosides were converted to their inosine or guanosine counterparts by adenosine deaminase (ADA) (Corey and Suhadolnik, 1996; Frederiksen, et al., 1996; Chassy and Suhadolnik, 1967; Baer et al., 1968; Pauwels et al., 1988; Biron et al., 1991; Marquez et al., 1990; Robins and Basom, 1973). In order to determine if there is any relationship between the enzymatic deamination with respect to the anti-HIV activity, enzymatic hydrolysis studies with adenosine deaminase for selective prodrugs (potent 8 & 9, moderately active 10 and slightly active or inactive 14) were carried out (Table 2). The preliminary qualitative assay indicates that, except compound 14, most of the studied compounds (6-13) were partially converted to DXG over the time. In quantitative studies, the most active compounds (8 and 9), the moderately active compound (10) and the slightly active compound 14 were selected for deamination. From the studies, we observed that after 240 min, a 89 % of DAPD (used as the positive control) (Furman et al., 2001) was converted into DXG, whereas the conversion was significantly lower in compounds 8, 9, and 10 (0.7 % 1.0 % and 1.1 %, respectively) in comparison to that of DAPD. Thus, these results didn’t show any significant correlation between the rate of hydrolysis and the antiviral activity in cell culture studies.

Table 2.

Anti-HIV activity and enzymatic hydrolysis of DAPD prodrugs

| Anti-HIV Activity(a) | Enzymatic Hydrolysis(b) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | R | EC50 (μM) | % | |

|

8 | NHEt | 0.41 ± 0.25 | 0.7 |

| 9 | NMe2 | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 1.0 | |

| 10 | NHi-Pr | 5.40 ± 5.20 | 1.1 | |

| 14 | NHBn | 44.90 ± 27.9 | 0.0 | |

| DAPD(c) | NH2 | 6.90 ± 4.70 | 89.0 | |

in human PBM cells unless otherwise indicated. Based on three replicate assays

percentage conversion of DAPD prodrugs to DXG by adenosine deaminase (bovine spleen) after 240 min. in pH 7.4 buffer solution at 37 ± 0.5 °C

DAPD was used as the positive control

In summary, we have synthesized various DAPD and DXG prodrugs. Some of the synthesized DAPD prodrugs (8, 9, 12) exhibited significantly enhanced anti-HIV activity in comparison to that of DAPD. DAPD-organic salts and L-5′-valyl DAPD also showed enhanced antiviral activity in comparison to DAPD, whereas the DXG prodrugs exhibited lower activity than the parent drug. However, there seems no correlation between the rate of hydrolysis and anti-HIV activity in vitro. Additional biological studies, including the anti-HIV activity against drug resistance mutants as well as pharmacokinetic studies, are warranted to assess the full potential of these (8,9,12) promising DAPD prodrugs.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 5′-O-valyl-DAPD.

Reagents and conditions: (i) DCC, DMAP, DMF (ii) DCM, TFA, 0-5 °C (iii) IPA, PL-HCO3 resin.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by NIH A125889 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Badet B, Julia M, Lefebvre C. The efficiency of diphenylsulfonium salts as alkylating agents. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1984;11:431–434. [Google Scholar]

- Baer HP, Drummond GI, Gillis J. Studies on the specificity and mechanism of action of adenosine deaminase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968;123:172–178. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J. Metabolism and mechanism of antiviral action of purine and pyrimidine derivatives. Pharm. World Sci. 1994;16:113–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01880662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi JJ, Marquez VE, Driscoll JS, Ford H, Mitsuya H, Shirasaka T, Aoki S, Kelley JA. Potential anti-AIDS drugs. lipophilic, adenosine deaminase-activated prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:1647–1655. doi: 10.1021/jm00109a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazmi HZ, Hammond JL, Cavalcanti SCH, Chu CK, Schinazi RF, Mellors JW. In vitro selection of mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase that decrease susceptibility to (-)-β-D-dioxolane-guanosine and suppress resistance to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1783–1788. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1783-1788.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzaria S, Pierra C, Bardiot D, Cretton-Scott E, Bridges EG, Zhou X-J, Standring D, Gosselin G. Monoval-LdC: efficient prodrug of 2′-deoxy-beta-L-cytidine (L-dC), a potent and selective anti-HBV agent. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2003;22:1003–1006. doi: 10.1081/NCN-120022723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron KK, De Miranda P, Burnette TC, Krenitsky TA. Selective anabolism of 6-methoxypurine arabinoside in varicella-zoster-infected cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2116–2120. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.10.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassy BM, Suhadolink RJ. Adenosine aminohydrolase, binding and hydrolysis of 2 and 6-substituted ribonucleosides and 9-substituted adenine nucleosides. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:3655–3658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Schinazi RF, Rajagopalan P, Chu CK, McClure HM, Boudinot FD. Pharmacokinetics of (-)-beta-D-dioxolane guanine and prodrug (-)-beta-D-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane in rats and monkeys. AIDS Res. Human Retrovir. 1999;15:1625–1630. doi: 10.1089/088922299309667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong Y, Borroto-Esoda K, Furman PA, Schinazi RF. Molecular mechanism of DAPD/DXG against zidovudine- and lamivudine- drug resistant mutants: a molecular modelling approach. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2002;13:115–28. doi: 10.1177/095632020201300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong Y, Chu CK. Molecular mechanism of dioxolane nucleoside against 3TC resistant M184V HIV mutant. Antiviral. Res. 2004;63:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CK, Ahn SK, Kim HO, Beach JW, Alves AJ, Jeong LS, Islam Q, Roey PV, Schinazi RF. Asymmetric synthesis of enantiomerically pure (-) (1R, 4R)-dioxolane thymine and its anti-HIV activity. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3791–3794. [Google Scholar]

- Chu CK, Yadav V, Chong Y, Schinazi RF. Anti-HIV Activity of (-)-(2R, 4R)-1-(2-Hydroxymethyl-1, 3-dioxolan-4-yl)- thymine against drug-resistant HIV-1 mutants and studies of its molecular mechanism. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:3949–3952. doi: 10.1021/jm050060l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CK, Beach JW, Jeong LS, Choi Bo.G., Comer FI, Alves AJ, Schinazi RF. Enantiomeric synthesis of (+) BCH-189 [(+)-(2S, 5R)-1- [2-(hydroxymethyl))-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine] from D-manose and its anti-HIV activity. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:6503–6505. [Google Scholar]

- Chulay J, Biron K, Wang L, Underwood M, Chamberlain S, Frick L, Good S, Davis M, Harvey R, Townsend L, Drach J, Koszalka G. Development of novel benzimidazole riboside compounds for treatment of cytomegalovirus disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999;458:129–134. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4743-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey JG, Suhadolnik RJ. Structural requirements of nucleosides for binding adenosine deaminase. Biochemistry. 1966;4:1729–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Daluge SM, Good SS, Falettto MB, Miller WH, St Clair MH, Boone LR, Tisdale M, Parry NR, Reardon JE. 1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1082–1093. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks S, Kessler H, Eron J, Thompson M, Raffi F, Jacobson J, Sista N, Bigley J, Rousseau F.4th International Workshop on HIV Drug Resistance & Treatment StrategiesSitges, Spain2000Abstract 5 [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Antiviral drugs: Current State of the Art. J. Clin. Virol. 2001;22:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher D, Bong R, Stewart BH. Improved oral drug delivery: Solubility limitations overcome by the use of prodrugs. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1996;19:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen S. Specificity of adenosine deaminase toward adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine analogues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;113:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman PA, Jeffrey J, Kiefer LL, Feng JY, Anderson KS, Borroto-Esoda K, Hill E, Copeland WC, Chu CK, Sommadossi J-P, Liberman I, Schinazi RF, Painter GF. Mechanism of action of 1-β-D-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane, a prodrug of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitor 1-β-D-dioxolane guanosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:158–165. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.158-165.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JE, Gerondelis PZ, Wainberg MA, Shulman NS, Haubrich RH, St Clair M. Nucleoside and nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors: a clinical review of antiretroviral resistance. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:489–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Miller M. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of isocyanurate-based antifungal and macrolide antibiotic conjucates-iron transport-mediated drug delivery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995;3:1519–1525. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynis D. Changing the salt, changing the drug. Pharm. J. 2001;266:322–323. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Wainberg MA, Nguyen-Ba P, L’Heureux L, de Muys JM, Rando RF. Anti-HIV-1 activities of 1,3-dioxolane guanine and 2,6-diaminopurine nucleosides. Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 1999;18:891–892. doi: 10.1080/15257779908041594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Wainberg MA, Nguyen-Ba P, L’Heureux L, de Muys JM, Bowlin TL, Rando RF. Mechanism of action and in vitro activity of 1′,3′-dioxolanylpurine nucleoside analogues against sensitive and drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2376–2382. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HK, Amidon GL.Targeted prodrug design to optimize drug delivery AAPS Pharmsci 20002Art.no.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy T. Managing the drug discovery/development interface. Drug Discov. Today. 1997;2:436–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Ahn SK, Alves AJ, Beach JW, Jeong LS, Choi Bo.G., Roey PV, Schinazi RF, Chu CK. Asymmetric synthesis of 1,3-dioxalane-pyrimidine nucleosides and their anti-HIV activity. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:1987–1995. doi: 10.1021/jm00089a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Schinazi RF, Nampalli S, Shanmuganathan K, Cannon DL, Alves AJ, Jeong LS, Beach JW, Chu CK. 1,3-Dioxolanyl purine nucleosides (2R, 4R) and (2R, 4S) with selective anti-HIV-1 activity in human lymphocytes. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:30–37. doi: 10.1021/jm00053a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Schinazi RF, Nampalli S, Shanmuganathan K, Jeong LS, Beach JW, Nampalli S, Cannon DL, Chu CK. L-β-(2S, 4S) and L-α-(2S, 4R)-dioxolanyl nucleosides as potential anti-HIV agents: Asymmetric synthesis and structure-activity relationships. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:519–528. doi: 10.1021/jm00057a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalezari JP, Aberg JA, Wang LH, Wire MB, Richard Miner R, Snowden W, Talarico CL, Shaw S, Jacobson MA, Drew WL. Phase I dose escalation trial evaluating the pharmacokinetics, Anti-human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) activity, and safety of 1263W94 in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men with asymptomatic HCMV shedding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2969–2976. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2969-2976.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Narayanasamy J, Schinazi RF, Chu CK. Phosporamidate and phosphate prodrugs of (-)-β-D-(2R, 4R)-dioxolane-tymine: synthesis, anti-HIV activity and stability studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;(14):2178–2189. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SJ, Holte S, Routy JP, Daar ES, Markowitz M, Collier AC, Koup RA, Mellors JW, Connick E, Conway B, Kilby M, Wang L, Whitcomb JM, Hellman N, Richman DD. Antiretroviral-drugresistance among patients recently infected with HIV. N. Engl J. Med. 2002;347:385–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis D, Mukherjee L, Hogg E, Fletcher C, Ogata-Arakaki D, Petersen T, Rusin D, Martinez A, Adams E, Mellors J, Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5165 team DAPD, NRTI-Modestly reduced viral load & no safety issues; 13 th CROI (Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Denver, Colorado. 2006; Feb-5-8. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez VE, Tseng CK-H, Mitsuya H, Aoki S, Kelley JA, Ford H, Roth JS, Broder S, Johns DG, Driscoll JS. Acid-stable 2′-fluoro purine dideoxynucleosides as active agents against HIV. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:978–985. doi: 10.1021/jm00165a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocroft A, Phillips AN, Friis-Moller N, Colebunders R, Johnson AM, Hirschel B, Saint-Marc JD, Staub T, Clotet B, Lundgren JD. Response to antiretroviral therapy among patients exposed to three classes of antiretrovirals: results from the EuroSIDA study. Antivir Ther. 2002;7:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels R, Baba M, Balzarini J, Herdewijin P, Desmyther J, Robins MJ, Zou R, Madej D, De Clercq E. Investigations on the anti-HIV activity of 2′, 3′-dideoxyadenosine analogues with modifications in either the pentose or purine moiety. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1988;37:1317–1325. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins MJ, Basom GL. Nucleicacid related compounds: Direct conversion of 2′-deoxyinosine to 6-chloropurine 2′-deoxyriboside and selected 6-substituted deoxynucleosides and their evaluation as substrates of adenosine deaminase. Can. J. Chem. 1973;51:3161–3169. [Google Scholar]

- Schinazi RF, Sommadossi JP, Saalmann V, Cannon DL, Xie M-W, Hart GC, Smith GA, Hahn EF. Activity of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine nucleotide dimers in primary lymphocytes infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1061–1067. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinazi RF, Cannon DL, Arnold BH, Martino-Saltzman D. Combinations of isoprinosine and 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine in lymphocytes infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;32:1784–1787. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka T, Murakami K, Ford H, Kelley JA, Yoshioka H, Kojima E, Aoki S, Broder S, Mitsuya H. Lipophilic halogenated congeners of 2′,3′-dideoxypurine nucleosides active against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 1990;87:9426–9430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Vig BS, Lorenzi PL, Drach JC, Townsend LB, Amidon GL. Amino acid ester prodrugs of the antiviral agent 2-bromo-5,6-dichloro-1-(beta-D-ribofuranosyl)benzimidazole as potential substrates of hPEPT1 transporter. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1274–1277. doi: 10.1021/jm049450i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyver LJ, Lostia S, Admas M, Mathew J, Pai BS, Grier J, Tharnish P, Choi Y, Chong Y, Choo H, Chu CK, Otto MJ, Schinazi RF. Antiviral activities and cellulose toxicities of modified 2′, 3′-dideoxy-2′,3′-didehydrocytidine analogues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3854–3960. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3854-3860.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamalet C, Fantini J, Tourres C, Yahi N. Resistance of HIV-1 to multiple antiretroviral drugs in France: a 6-year survey (1997-2002) based on an analysis of over 7000 genotypes. AIDS. 2003;17:2383–2388. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000076341.42412.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MA, Kessler HA, Eron JJ, Jr., Jacobson JM, Adda N, Shen G, Zong J, Harris J, Moxham C, Rousseau FS, DAPD 101 Study Group Short-term safety and pharmacodynamics of amdoxovir in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2005;19:1607–1615. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000186822.68606.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Brenner B, Wainberg MA. Relationships among various nucleoside resistance-conferring mutations in the reverse transcriptase of HIV-1. J. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2004;53:53–57. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince R, Hua M. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of carbocyclic 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy 2,6-disubstituted purine nucleosides. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:17–21. doi: 10.1021/jm00163a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley S. Individualized therapy for the treatment-experienced patient. AIDS Read. 2003;13(6 Suppl):S11–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, Rezende MM, Deng WP, Herbert B, Daly JW, Roger JA, Kirk KL. Synthesis of 2′,5′-dideoxy-2′,5′-difluoroadenosine: Potent P-site inhibitors of adenyl cyclase. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1207–1213. doi: 10.1021/jm0303599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]