Abstract

Background/Objective:

Pressure ulcers are a serious complication for people with spinal cord injury (SCI). The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (CSCM) published clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) that provided guidance for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment after SCI. The aim of this study was to assess providers' perceptions for each of the 32 CPG recommendations regarding their agreement with CPGs, degree of CPG implementation, and CPG implementation barriers and facilitators.

Methods:

This descriptive mixed-methods study included both qualitative (focus groups) and quantitative (survey) data collection approaches. The sample (n = 60) included 24 physicians and 36 nurses who attended the 2004 annual national conferences of the American Paraplegia Society or American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses. This sample drew from two sources: a purposive sample from a list of preregistered participants and a convenience sample of conference attendee volunteers. We analyzed quantitative data using descriptive statistics and qualitative data using a coding scheme to capture barriers and facilitators.

Results:

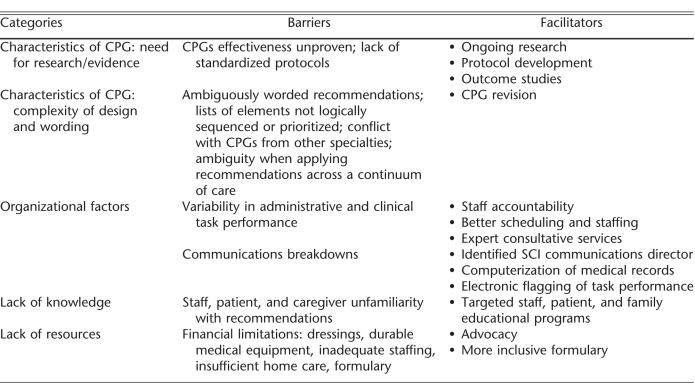

The focus groups agreed unanimously on the substance of 6 of the 32 recommendations. Nurse and physician focus groups disagreed on the degree of CGP implementation at their sites, with nurses as a group perceiving less progress in implementation of the guideline recommendations. The focus groups identified only one recommendation, complications of surgery, as being fully implemented at their sites. Categories of barriers and facilitators for implementation of CPGs that emerged from the qualitative analysis included (a) characteristics of CPGs: need for research/evidence, (b) characteristics of CPGs: complexity of design and wording, (c) organizational factors, (d) lack of knowledge, and (e) lack of resources.

Conclusions:

Although generally SCI physicians and nurses agreed with the CPG recommendations as written, they did not feel these recommendations were fully implemented in their respective clinical settings. The focus groups identified multiple barriers to the implementation of the CPGs and suggested several facilitators/solutions to improve implementation of these guidelines in SCI. Participants identified organizational factors and the lack of knowledge as the most substantial systems/issues that created barriers to CPG implementation.

Keywords: Decubitus ulcer, Skin ulcer, Pressure ulcer, Practice guidelines, Evidence-based medicine, Prevention, Spinal cord injuries

INTRODUCTION

Background and Review of Literature

More than 30,500 new spinal cord injuries (SCI) occurred in the United States (US) from 1973 through 2003, with total direct costs for all causes of SCI in the US exceeding $7.7 billion annually (1,2). Pressure ulcers are a frequent and potentially life-threatening complication of SCI. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in persons with SCI varies due to different methods of measurement and calculation of prevalence, case mix, and data sources but is estimated to range from 8% within the first postinjury year to as high as 33% of persons with SCI who reside in the community (3).

In August 2000, the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (CSCM) published Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals (4) to describe evidence-based strategies for identifying risks and reducing the incidence, prevalence, and recurrence of pressure ulcers in persons with SCI. The CSCM based these clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations on an extensive review of the available scientific literature. On questions for which the scientific literature could not provide guidance, the consortium sought and utilized expert consensus.

The purpose of this mixed-methods descriptive study was to determine providers' perceptions of the pressure ulcer CPG recommendations. Study questions included:

How strongly did providers agree or disagree with each of the 32 recommendations?

Had providers implemented each recommendation at their facilities?

What were the barriers and facilitators for implementing these recommendations?

Proposed models for implementing evidence-based practice (EBP) are the subject of debate (5–8). Much of the older evidence suggested that strategies to reduce barriers to implementation have been more successful using a multifaceted approach compared with a single intervention (9). More recently, a review of the literature on effectiveness and efficiency of CPG dissemination and implementation strategies found no relationship between the number of intervention components and the effectiveness of interventions (10).

Successful implementation must include developing a change proposal; identifying barriers to change; linking interventions to obstacles; and developing, evaluating, and implementing the plan (5). Negative beliefs and attitudes of health care providers who are responsible for carrying out specific recommendations can inhibit implementation, regardless of the theory used to facilitate implementation of change (11). The success of adopting CPG recommendations depends on such factors as organizational culture, leadership, and coordination among disciplines.

In SCI research, Xakellis and colleagues (12) found that implementation of a CPG-based pressure ulcer prevention protocol, without addressing the barriers to clinical integration, resulted in less-than-optimal long-term clinical outcomes. Recent research conducted among veterans with SCI in the Department of Veterans Affairs addressed lessons learned about the importance of eliminating barriers to integrate CPGs into SCI care (13,14). Barriers to CPG implementation may be categorized into (a) organizational factors, (b) lack of education/training, (c) lack of resources, (d) need for research/evidence, and (e) complexity of design and wording.

Organizational Factors. Instituting inter- and intrafacility standardization for implementation of CPGs is a daunting goal that requires system-wide support. Implementation can be fostered by “clinical champions” who encourage staff ownership and “buy in” of change at all levels (14).

Lancellot (15) described how communication breakdowns have been reduced by the designation of a SCI clinical nurse specialist to channel communication regarding pressure ulcer prevention among SCI team members, across shifts, and when patients are in other areas of the facility (eg, operating room, radiology, intensive care). Expert organizational and technological consultation also aids managers, administrators, and clinicians to implement policy and procedural changes necessary for CPG implementation. Electronic information systems enhance the process of care and clinical communications across service lines (16), expand access to medical records, flag timely task performance, and provide benchmarks for outcome monitoring (17–20).

Lack of Education/Training. Three educational models that address shortcomings in education and training are (20) (a) self-directed learning, (b) small-group learning, and (c) organizational learning. In self-directed learning, the learner identifies and uses resources drawn from human resources, (eg, colleagues, coworkers), material resources (eg, journals), and specialty training resources (eg, formal continuing education programs) (21). Small-group learning facilitates change-focused education; examples include working with patients, collaborating on teams with other health care personnel, and consulting with colleagues (22). Organizational-wide learning is supported by administrative structures that provide continuous learning opportunities that encourage collaboration within the organization and that foster links between the organization and external training resources (23).

Lack of Resources. Economic considerations heavily influence implementation of CPGs. Today, efforts to contain physician and health care organizational spending reverberate throughout the US health care services. Assumptions about what is possible and desirable in clinical approaches must be tempered by questions of cost efficiency and current levels of third-party payer reimbursement. To be effective, emerging strategies for influencing the affordability of SCI care are likely to require a greater level of partnership between payers, providers, and other stakeholders.

Need for Research/Evidence. Need for scientific evidence is another barrier to CPG implementation. Outcomes research can fuel advocacy if a positive association is demonstrated between CPG best practices and improved health care quality and/or reduced costs (18). Clinical protocol development, which is research based, is needed to guide medical decision making and treatment approaches while allowing for the interplay of clinical judgment and experience (24,25). Clinical protocol development requires research addressing pressure ulcer etiology, risk factor assessment, wound assessment, wound management, positioning, pressure-reducing technologies, nutrition, psychosocial factors, surgical evaluation, and postdischarge follow up. Evaluative studies on the quality of medical equipment and products (eg, wheelchairs, mattresses, cushions) foster innovative, wound-preventative design.

Complexity of Design and Wording. CPG design and wording were perceived to strongly influence the degree of implementation for specific CPG recommendations. Clear concepts, precise wording, and stating objectives in quantifiable terms enable CPG authors to curb misinterpretation. Clinical practice guidelines that strike a balance between sensitivity and specificity will be sufficiently broad to apply across multiple clinical scenarios and yet detailed enough for use with individual patients. Language must be crafted based on medical training, experience, personal patient knowledge, and direct examination of SCI wound care issues. Specification of task performance frequency also aids in implementation (eg, provision of timelines for visual and tactile wound inspections and other patient care tasks). Wording and format recommendations include (a) establish a workgroup to develop criteria for writing CPG recommendations that can be measured and implemented; (b) revise criteria for evaluating evidence to ensure that the evidence is specific to SCI; (c) develop a document and accompanying “toolkit” on implementing CPG; (d) improve CSCM marketing to reflect the rigor of its CPG development process; and (e) discourage long lists of elements, focusing instead on weighting the list (14).

In summary, CPGs have become an accepted way of disseminating EBP. Although much debate exists over the best way to implement change within clinical practice, barriers to implementation must be identified and addressed regardless of the implementation approach. In this article, we describe providers' perceptions of the SCI pressure ulcer CPG. Our ultimate goal is to facilitate improved care and success in pressure ulcer prevention and management in this high-risk population.

METHODS

Study Design

This mixed-methods study used both a written survey and focus groups to determine providers' perceptions of the SCI pressure ulcer CPG. A local institutional review board approved this study. The SCI pressure ulcer CPG was developed by the CSCM and published in 2000 (4). The consortium consists of 19 member organizations representing numerous disciplines, including medicine and rehabilitation specialties, nursing, occupational and physical therapy, psychology, and consumers and veterans. The 32 recommendations included in the guidelines were developed based on extensive review of the literature, existing scientific evidence, and expert opinion in the absence of scientific evidence (Table 1). The guidelines are intended for numerous provider audiences, as well as people with SCI families and significant others.

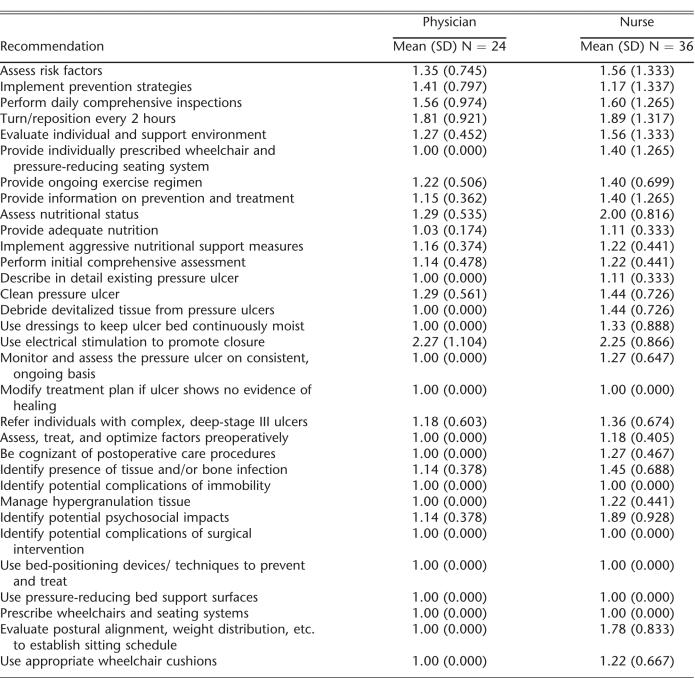

Table 1.

Physician and Nurse Ratings of Agreement with SCI-Related Pressure Ulcer Guideline Recommendations

Sample

The sample consisted of physicians and nurses who were attending the jointly held national conferences in 2004 of the American Paraplegia Society and the American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses. At first, we selected a purposive sample from the list of registrants of the conference. Purposive sampling is a technique of selecting subjects based on their knowledge and expertise related to the purpose of the research (26). We invited both physicians and nurses to the focus groups from registrants who regularly attended the SCI annual conferences. The researchers knew the invitees either personally or by their reputations for expertise in SCI to ensure rich data about implementing the CPG. We mailed invitations to potential participants just prior to the conference and asked them to respond by e-mail. After this initial recruitment, we felt that more participants were needed, so we set up a study recruitment table at the conference registration area to enlist additional participants for a convenience sample.

Data Collection Instruments

The study used 3 data instruments: (a) demographics questionnaire, (b) recommendations questionnaire, and (c) focus group guide. The demographics questionnaire included 5 forced-choice questions addressing the participant's age, care type, role, practice site, and experience in SCI care and 1 open-ended question for additional comments about CPG implementation. The recommendations questionnaire consisted of Likert-style questions for each of the 32 recommendations in the pressure ulcer CPG (Table 1) that addressed the participant's level of agreement with the recommendation (rated on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = completely agree and 5 = completely disagree) and whether or not the recommendation was currently in place at the participant's practice site. The focus group guide was developed from other guides the research team had used to explore barriers and facilitators to CPG implementation. This resource included a narrative on the study's purpose, focus group procedures, and focused questions regarding barriers and facilitators to each CPG recommendation.

Data Collection Procedures

Six separate 90-minute focus groups were conducted, 3 for nurses and 3 for physicians. A trained focus group facilitator explained the research goals and focus group procedures; obtained informed consent signatures, including permission to audiotape; and invited respondents to complete the demographics and recommendations questionnaires. The facilitators then guided the discussion of CPG implementation barriers and facilitators, proceeding through as many of the 32 total CPGs as possible in the 90 minutes allotted per group. Each subsequent focus group began where the previous group stopped, cycling through the recommendations so that all 32 of the recommendations were covered approximately twice.

To stimulate discussion, the facilitator used standard group process techniques, such as generic prompts (eg, “Tell me more”), summarizing statements, asking for like and contrasting opinions, controlling dominant participants, and calling on less participative respondents. For each major point, group consensus on prioritization was solicited (eg, “Which barrier in this list is the greatest obstacle?”). Techniques to ensure data included (a) the use of experienced focus group facilitators, (b) handwritten record of key points during each focus group session, (c) audiotaping of each session, and (d) consensus-based development of a coding scheme by 5 of the author/investigators.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the demographic and survey data using descriptive statistics. Hand-written notes from focus groups were analyzed using content analysis (27). The goal of the content analysis was to understand disagreements in acceptance of recommendations and to identify the most salient barriers to implementing each recommendation as identified by the participants. The group of investigators reviewed the hand-written notes immediately after all focus groups were completed.

Using a consensus approach, the research team developed a preliminary coding scheme and refined it based on discussion and reviewing notes again. Categories included (a) characteristics of CPGs: need for research/evidence, (b) characteristics of CPGs: complexity of design and wording, (c) organizational factors, (d) lack of knowledge, and (e) lack of resources. The team developed definitions for each category and identified examples for each category. Taped transcripts of the groups were used to validate hand-written notes and to ensure that information was not missed. One data analyst coded all of the transcripts. This analyst further refined the definitions and identified salient quotes to illustrate the categories

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 36 nurses and 24 physicians participated as respondents in focus groups. The mean age of respondents was 51 and 49 years, respectively, for nurses and physicians. The mean length of time working in an SCI setting was 13 years for both groups. Physicians were more likely to have positions focused on direct patient care (96%) compared with the nurses (69%). The primary practice site of the nurses was the acute care hospital setting (43%), whereas the primary practice site of the physicians was the rehabilitation center (42%).

Agreement with CPG

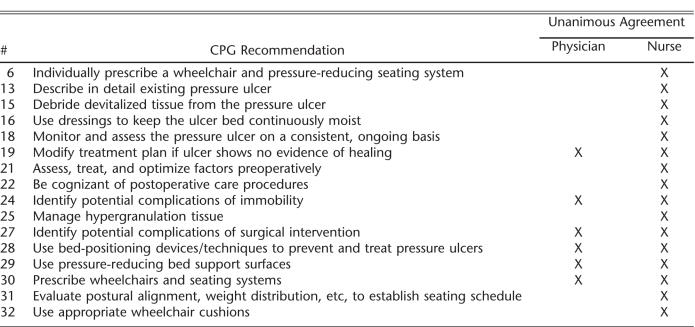

Levels of agreement across all 32 recommendations were very high for both physicians and nurses (Table 2). Physicians unanimously agreed with 16 of the 32 recommendations, and nurses unanimously agreed with 6. The 2 CPG recommendations that received the lowest levels of agreement by both the nurses and physicians were the use of electrical stimulation and turning/repositioning every 2 hours. The physician group also reported a low level of agreement with the CPG related to the psychosocial impact of pressure ulcers.

Table 2.

Recommendations Receiving Unanimous Agreement

Degree of Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines

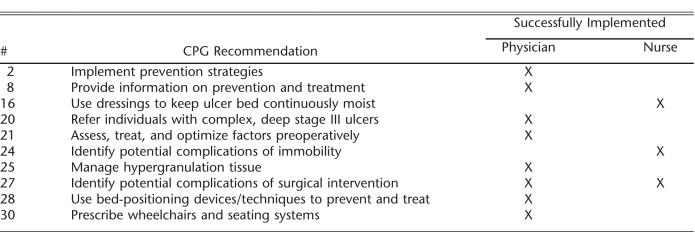

Physicians identified 8 and the nurses 3 CPG recommendations that they believed were fully implemented (Table 3). The only recommendation that both groups perceived was fully implemented was to identify potential complications of surgical intervention.

Table 3.

Recommendations Perceived to Be Successfully Implemented

Focus Group Findings

Respondents identified numerous barriers to pressure ulcer CPG implementation that fit into the 5 domains identified in “data analysis.” For each domain, we will describe the barriers perceived by the groups, and the facilitators (solutions) offered (Table 4).

Table 4.

Barriers and Facilitators to Guideline Implementation

Characteristics of Clinical Practice Guidelines: Lack of Evidence. Nurses and physicians indicated a lack of evidence for several recommendations, especially those that focused on SCI wound care procedures and technologies.

Representative quotes include:

“…a very big problem is the lack of research. There is a lack of data available for repositioning schedules…” (CPG #4) (nurse)

“…there is a need for some technological development in wheelchair standards that have pressure reducing features in the lower regions…” (CPG #31) (nurse)

Respondents emphasized the need for research to further develop standardized clinical protocols to assist medical practitioners to implement best practice care for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. Respondents also discussed the need for uniform, valid, and reliable SCI pressure ulcer assessment instruments specific to certain populations, including children and persons of color.

Characteristics of Clinical Practice Guidelines: Complexity of Design and Wording. Respondents viewed the guideline recommendations as too complex, based on the number of recommendations and subrecommenda-tions, as well as the complexity embedded within each recommendation. They noted that some recommendations contained long lists of elements that were not necessarily logically sequenced or prioritized. Respondents reported that certain pressure ulcer CPG recommendations conflicted with guideline recommendations from other disciplines, such as orthopedics and neuro-surgery.

Representative quotes include:

“… not everyone is going to know what ‘minimum mechanical force’ is…” (CPG #14) (nurse)

“I'm not sure the recommendation should be an ‘exercise’ regimen. It should be an ‘activity’ regimen…” (CPG #7) (nurse)

“… I would change the word ‘aggressive’ to ‘optimal.’ I think it would be ‘optimal’ for everyone in a different way…” (CPG #11) (nurse)

“…I would personally prefer to see the biochemical parameters listed first as the most reliable source… so that the dietary intake and anthropometric measurements will appear to be more secondary…” (CPG #9) (nurse)

Respondents indicated that redesign and/or rewording of certain recommendations would increase their ease of interpretation and thus their ability to be implemented and usefulness.

Organizational Factors. Lack of standardization in organizational factors, such as clinical, administrative, and communications processes, was a key issue addressed by the pressure ulcer CPG recommendations. Respondents reported uneven implementation of the pressure ulcer CPG across hospital disciplines and services, as well as across the continuum of care (eg, across hospital-, community-, and home-based care settings). Respondents attributed organizational barriers to underdeveloped or ineffective communication channels and ill-conceived or nonexistent policies and procedures. Respondents complained that clinicians external to SCI minimized the importance of pressure ulcers in persons with SCI. Respondents noted that when their patients received care (eg, intraoperative care, radiology, diagnostic tests, immediate postacute SCI outside SCI, rehabilitation units or settings), the respondents had little control over pressure ulcer prevention and management.

Representative quotes include:

“…nurses are not allowed to debride in our region…” (CPG #15) (nurse)

“… electrical stimulation goes against the guidelines set out by our region; we haven't had enough literature to support its use…” (CPG #17) (nurse)

“…there's great variability in plastic surgeons on their surgical approach…” (CPG #20) (physician)

“…progressively mobilize the individual to a sitting position over at least 4 to 8 weeks… usually, we remobilize people over 10 days…” (CPG #22) (physician)

Respondents noted the need to improve organizational factors related to (a) pressure ulcer risk assessment; (b) pressure ulcer healing; (c) repositioning schedules; (d) nutritional assessment; (e) use of appropriate specialty mattresses, beds, wheelchairs, and cushions; and (f) documentation.

Lack of Knowledge. Participants identified informational deficiencies as critical CPG barriers. They noted knowledge gaps on the part of staff, patients, and family and the unwillingness of some staff, particularly physicians, to change their clinical approaches despite exposure to EBP.

Representative quotes include:

“… most physicians and most nurses have no idea how to manage electrical stimulation…” (CPG #17) (physician)

“…there are a lot of discrepancies in the ability of nurse assessors to appropriately characterize (wound) staging…” (CPG #13) (physician)

“…A lot of people aren't aware of the products that are available for escharmatic debriding, including physicians, and they often don't know how to use it or what to expect from the product…” (CPG #15) (nurse)

Respondents frequently mentioned the need for more educational initiatives to introduce new and emerging SCI technologies and products to providers. They believed that education and training initiatives ideally should begin at new staff orientation and frequently reoccur for patients, family, and multidisciplinary staff through work-, home-, and community-based forums.

Lack of Resources. Respondents identified financial and material limitations, as well as private and third-party payment limitations, as substantial barriers to pressure ulcer CPG implementation, both within health care facilities and the community. Resource limitations mentioned ranged from uneven urban/rural service accessibility to clinical services, lack of durable and disposable medical equipment and supplies, inadequate staffing within the hospital, and constraints on reimbursable home care services.

Representative quotes include:

“… the cost of bed-positioning devices limits the number that we're able to purchase…” (CPG #28) (nurse)

“ …we find that many times… the dressings are not changed as ordered, and usually it's an indication of (inadequate) staffing” (CPG #16) (physician)

“… not having the appropriate tools (in hospital) to use to cleanse the wound…” (CPG #14) (nurse)

“…lack of availability and accessibility to some of the bed positioning devices in the community…” (CPG #28) (nurse)

Respondents stated that national SCI advocacy campaigns should emphasize the incongruities among Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance reimbursement rates and formularies that negatively affect CPG implementation. They also felt that professional credentialing and regulatory agencies could do more to promote CPG compliance.

DISCUSSION

Clinical practice guidelines are tools for guiding clinician behavior and decision making. Guideline development and dissemination are insufficient to change clinical practice in general. The results of our study confirmed that implementation is low for the pressure ulcer CPG in particular. Identification of clinician-perceived barriers to implementation of the CPG provides the groundwork to develop implementation strategies. Focus group participants identified barriers in 5 domains: (a) characteristics of CPGs: need for research/evidence, (b) characteristics of CPGs: complexity of design and wording, (c) organizational factors, (d) lack of knowledge, and (e) lack of resources.

A particularly difficult barrier, categorized either as organizational factors or lack of knowledge, refers to care of the patient when he or she is being cared for outside the SCI/rehabilitation unit, where the focus is not necessarily on preventing pressure ulcers. This might occur, for example, during pressure ulcer reconstructive surgery, which is usually performed in community or university hospitals. To facilitate this barrier, all non-rehabilitation hospitals need evidence-based education and training on how to care for persons with SCI. Each nonrehabilitation center should post basic “rules” for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers and use the CPG as a guide to expand the knowledge of the nonexpert staff.

Respondents noted that there was a lack of evidence for the majority of recommendations in the pressure ulcer CPG. Only 8 of the 32 recommendations had level 1 evidence (ie, large, randomized trials with clear-cut results and a low risk of error). This may have reduced the respondents' levels of agreement with the recommendations and may be responsible for the low levels of implementation. Respondents also noted the complexity of the CPG. This CPG has 32 major recommendations with 101 bullets that cover a wider scope and depth than some other CPGs and present barriers to implementation.

Differences in nurse and physician responses could be attributed to (a) different job responsibilities; (b) nurses typically spending more time at the patient's bedside than the physician (eg, dressing changes); (c) physicians' having clinical privileges to order the necessary consults, specialty support surfaces, dressing type/frequency, and a myriad of other types of orders and nurses not typically having a scope of practice for these interventions; (d) physicians typically being able to perform various procedures and nurses not having the skills/licensure to perform these interventions (eg, debridement); and (e) some of the recommendations being the purview of other disciplines (eg, recommendations aimed at dietitians and therapists).

Study limitations include:

There was some overlap in representation of some SCI centers; however, the sample was not large enough to make site comparisons between nurses and physicians at the same site.

Due to the long list of recommendations in this CPG, participants may not have had sufficient time to fully identify barriers and facilitators.

Although subjects were asked about their levels of agreement with CPG recommendations, we did not ask for explanations when they disagreed with a particular recommendation(s). For example, we had no way of knowing if participants disagreed with the evidence substantiating the CPG recommendation or if they did not believe that the CPG recommendation was important or capable of being implemented at their facility.

This study did not determine if the main obstacle for CPC implementation was a lack of clinician knowledge or the failings of the CPG (complexity, lack of evidence).

An alternative approach might have been to provide some minimal education to participants about the CPG recommendations and their evidence prior to their participation in the study so that their levels of agreement would be better informed.

This study does not attempt to address the issues of whether or not the CPG is written in such a manner that the recommendations can be implemented, whether providers are familiar enough with specific CPG recommendations, or whether the incentives are adequate to induce providers to use the CPG.

The sample consisted of only physicians and nurses, even though other professionals, such as physical therapists, psychologists, and dietitians, are involved in guideline implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals (4) identifies strategies to reduce the incidence, prevalence, recurrence, and management of pressure ulcers in patients with SCI. Nurses and physicians completed a survey and participated in focus groups. Quantitative and qualitative data captured providers' degree of CPG agreement, their perception of the degree of CPG implementation, and participants' identification of barriers and facilitators to implementation. Participants indicated that consistent and systematic implementation of CPG recommendations requires changes in organizational factors, education, increased resources, further research/evidence, and CPG clarification and/or rewording.

Lessons learned by this study include:

Organizational factors that present barriers to implementing the CPG must be addressed, including clinical tools to facilitate implementation of recommendations (eg, algorithms, best-practice protocols, systematic tracking of treatment approaches).

A unit-based, systematic approach to implement CPG recommendations is optimal (eg, unit-based interdisciplinary task force, unit “champions”). One cannot assume that simply because the CPG is widely distributed that the recommendations will be implemented.

Given the need to partner with clinicians outside of the SCI or rehabilitation unit to implement the recommendations, facilities should adopt a systematic approach to implementing CPG recommendations (eg, policies and procedures developed by a hospital skin committee, standardizing best practices) within the facility where the SCI/rehabilitation unit is based.

CPG educational materials should be developed that target all disciplines, nonprofessional staff, patients, and home caregivers (eg, pressure ulcer prevention strategies, patient behavioral modification techniques, comprehensive assessment).

The impact of policy and reimbursement procedures on the capability of providing CPG-recommended care should be determined (eg, Medicare-reimbursed supplies/equipment, channels to facilitate access to facility and/or external resources, advocacy of flexibility in formulary controls). By the same token, larger efforts to implement these CPG recommendations may fail due to a lack of specificity of who is supposed to do what and if local standards and practices are not taken into consideration.

Research involving pressure ulcer prevention and management in persons with SCI should be conducted to justify recommendations, especially those that are costly to implement (eg, adjunctive topical therapy, specialty support surfaces and other technologies). SCI clinicians have been found to place more value on research conducted in SCI and are less likely to accept findings obtained from non-SCI populations.

The CSCM and other guideline development panels should carefully consider the impact of the wording and complexity of each guideline recommendation because this affects implementation. Wording should be modified in future editions of the CPG to enhance precision, specificity, prioritization, and operational definitions of terms.

CPG implementation is a complex process that involves the entire continuum of patient care, crosses service lines within the health care facility, and extends into the community. The findings of this project will hopefully stimulate implementation and discussion of the pressure ulcer CPG across sites. Future research is needed to identify aspects of change that must be managed by the system instead of each facility and establish evidence-based gold standards to evaluate outcomes.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital. This research was also supported by the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry, Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), and the United Spinal Association. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the hospital, PVA, or Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- DeVivo MJ. Causes and costs of spinal cord injury in the United States. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:809–813. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AB, Dijkers M, DeVivo MJ, Poczatek RB. A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries: change and stability over 30 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1740–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein AR, Horwitz RI. Problems in the “evidence” of “evidence-based medicine.”. Am J Med. 1997;10:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. Br Med J. 1997;315:418–421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulding NT, Silagy CA, Weller DP. A framework for effective management of change in clinical practice: dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guidelines. Qual Health Care. 1999;8:177–183. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.3.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image J Nurs Scholar. 1999;31:317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Mittman BS, Yano EM, Mulrow CD. From understanding health care provider behavior to improving health care: the QUERI framework for quality improvement. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Med Care. 2000;38(Suppl 1):I129, I141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Getting evidence into practice. Effect Health Care. 1999;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8iii–iv:1–72. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach Evidence-Based Medicine. New York, NY: Churchill Living-stone; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Xakellis GC, Frantz RA, Lewis A, Harvey P. Translating pressure ulcer guidelines into practice: it's harder than it sounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14:249–256. 258. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guihan M, Simmons B, Nelson A, Bosshart HT, Burns SP. Spinal cord injury providers' perceptions of barriers to implementing selected clinical practice guideline recommendations. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:48–58. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guihan M, Bosshart HT, Nelson A. Lessons learned in implementing SCI clinical practice guidelines. SCI Nurs. 2004;21:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancellot M. CNS combats pressure ulcers with skin wound assessment team (SWAT) Clin Nurse Spec. 1996;10:154–160. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199605000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz J, Bates-Jensen B. Algorithms, critical pathways, and computer software for wound care: contemporary status and future potential. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2001;47:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M, Balas EA, Mitchell JA, Ewigman BC. Effect of physician reminders on preventative care: meta-analysis of randomized, clinical trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;18:121–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ. Organizational interventions to encourage guideline implementation. Chest. 2000;118:40S–46S. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg WE, Bass M, Calonge N, Crouch H, Salenstein G. Randomized controlled study of customized preventative medicine reminder letters in a community practice. Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:81–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RD, Bennett NL. Learning and change: implications for continuing medical education. Br Med J. 1998;316(7129):466–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RD, Davis DA, Wentz D. The case for research in continuing medical education. In: Davis DA, Fox RD, editors. Physicians as Learners. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 1994. pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fox RD, Mazmanian PE, Putnam RW, editors. Change and Learning in the Lives of Physicians. New York, NY: Praegar; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins K, Marsick V. Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systematic Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy DM. Clinical policies and quality clinical practice. New Engl J Med. 1982;6:343–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208053070604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy DM. Designing a practice policy: standards. Guidelines and options. JAMA. 1990;263:3077, 3081, 3044. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.22.3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weber R. Basic Content Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]