Abstract

Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations were carried out in a case of pleomorphic adenoma with bone formation, occurring in the chin of a 34-year-old Japanese man. Examination results showed the modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells reacted positively to S-100 protein. The S-100-positive modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells were proliferated in the closely related area of the bone tissue. Furthermore, positive reaction was detected in the bone forming cells: osteoblasts and osteocytes. These cells also reacted positively to Runx2 as a marker of bone forming cells. These results suggest that the origin of the bone forming cells in this case of pleomorphic adenoma was modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells.

Keywords: Bone forming cells, Immunohistochemical characteristics, Pleomorphic adenoma, Modified myoepithelial cell, Trans-differentiation

1. Introduction

Pleomorphic adenomas can display a variety of histopathological features, such as myxomatous changes, cartilage and bone formation in so-called stromal tissue of the neoplasms. According to the World Health Organization, pleomorphic adenoma is a tumor of variable capsulation, characterized microscopically by architectural rather than cellular pleomorphism. Epithelial and modified myoepithelial elements intermingle most commonly with tissue of mucoid, myxoid or chondroid appearance 1. We believe that a “modified myoepithelial element” (neoplastic myoepithelium) may play an important role in these histopathological changes. There have been few case reports of pleomorphic adenoma with typical bone tissue formation 2, 3, 4, or examinations of the origin of the bone forming cells, using immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Recently, we experienced a case of pleomorphic adenoma with large typical bone formation 5, and in this paper we examined the case using immunohistochemical techniques to study the origin of the bone forming cells (osteoblasts and osteocytes).

2. Materials and Methods

Examination material

The patient, a 34-year old Japanese male noticed a swelling at the region of his chin approximately 1 year ago. The patient was referred to a dental clinic, where initial examination revealed a small painless nodular swelling, soybean in size, of the chin with normal surface epithelium. The patient was prescribed antibiotics and analgesics, but these did not relieve his symptoms. Based on the subsequent clinical course, a clinical preoperative diagnosis of fibroma was made. Surgical enucleation of the lesion was performed under local anesthesia. Post-operative local healing was uneventful.

Examination methods

Immediately after surgical removal, from the patient, the materials were fixed in 10 % neutral buffered formalin fixative solution. The materials were then dehydrated by passage through a series of ethanol and embedded in paraffin. After sectioning, the specimens were examined histopathologically (hematoxylin-eosin: HE) and by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Immunohistochemical examination was carried out using DAKO EnVisionTM+Kit-K4006 (Dako Cytomation, Copenhagen, Denmark) and 2 monoclonal antibodies: S-100 (NCL-S100p; Novo, Newcastle, UK), Runx2 (M70: sc-107589; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, California, USA). DAB was applied for the visualization of immunohistochemical activity. We included immunohistochemical staining using PBS in place of the primary antibody as a negative control.

3. Results

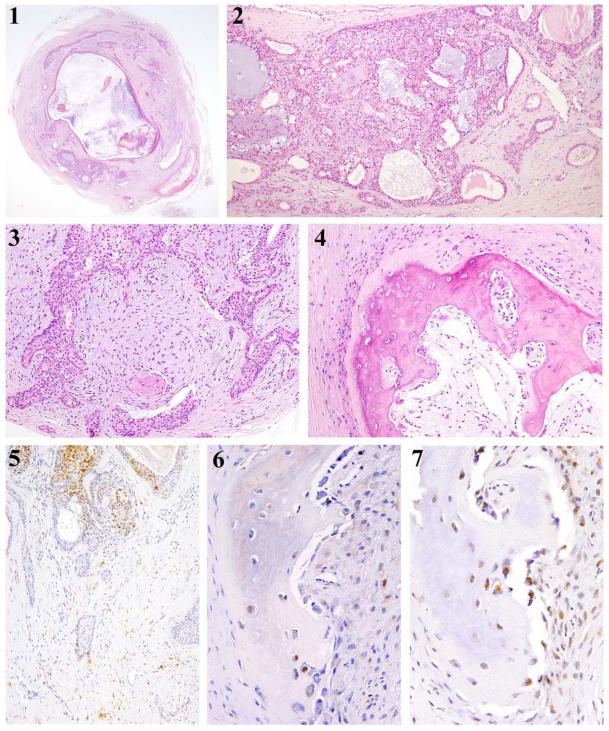

The resected material, 8 x 6 x 6mm in size, was completely circumscribed with a fibrous capsule [Fig 1 (1)]. Tumor tissue was composed of proliferating tumor nests in the fibrous tissues. In the center of the tumor mass, there were some enlarged cystic lumens. The proliferating neoplastic cells consisted of ductal cells, sometimes showing formation of lumens, and modified myoepithelial cells, appearing in the outer layer. Some lumens had eosinophilic material [Fig 1 (2)]. In the area of so-called stromal tissue, spindle-shaped cells proliferated in close or in coarse, and myxomatous lesions were observed. Furthermore, spindle-shaped and oval-shaped neoplastic cells proliferated in the so-called stromal tissues [Fig 1 (3)].

Figure 1.

(1) Tumor tissue is completely circumscribed with a fibrous capsule (HE, x 10). (2) The proliferating neoplastic cells consisted of ductal cells, sometimes showing formation of luminal formation with or without eosinophilic material (HE, x 30). (3) Spindle-shaped and oval-shaped neoplastic cells proliferating in so-called stromal tissues (HE, x 50). (4) Bone formation is observed in the tumor tissue. The bone has marrow-like tissue in the center of the bone tissue mass (HE, x 100). (5) S-100 positive products are detected in the neoplastic cells. Spindle-shaped or oval-shaped modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells react positively to S-100 protein (IHC, S-100, x50). (6) In some cases, S-100 positive products were detected in the cytoplasm of osteoblasts (IHC, S-100, x50). (7) The osteoblasts and osteocytes are both positive to Runx2 (IHC, Runx2, x50).

Bone formation was observed in the area near the fibrous capsule. The bone had marrow-like tissue in the center of the bone tissue mass. The bone tissue was composed primarily of compact bone. The osteoblasts were typically arranged in the outer surface of the bone tissue. In contrast, on the side of marrow-like tissue, arrangements of both osteoblasts and osteoclasts were observed [Fig 1 (4)]. In some instances, there were remodeling lines which were deeply stained with hematoxylin.

Immunohistochemically, S-100 protein-positive products were detected in the cytoplasm of modified neoplastic cells in the neoplastic cell nests. Spindle-shaped or oval-shaped modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells, in the so-called stromal tissue, reacted positively to S-100 protein [Fig 1 (5)]. The S-100 positive cells coarsely proliferated in most stromal tissues, close to the bone tissues. Furthermore, the S-100 positive products were detected in the cytoplasm of some osteoblasts and osteocytes [Fig 1 (6)]. The osteoblasts and osteocytes were both positive to Runx2 [Fig 1 (7)].

4. Discussion

The histopathological pattern of pleomorphic adenoma is variable. Although there are some case reports of bone formation in pleomorphic adenoma 2, 3, 6-9, Shigeishi et al. 3 noted that bone formation in pleomorphic adenoma is a rare finding, and only several cases have been reported. Yates and Paget 9 described a case of pleomorphic adenoma of the submandibular gland with trabecular bone formation, and the bone was formed by endochondral ossification. On the other hand, Lee et al. 7 mentioned in their case report of pleomorphic adenoma with bone formation that the bone matrix was deposited directly by the metaplastic myoepithelial cells rather than by endochondral ossification. Hamakawa et al. 6 noted that bone tissue in pleomorphic adenoma was formed mainly by direct deposition of the osteoid tissue produced by the modified myoepithelial cells and via partial endochondral ossification mode. However, Takeda and Yamamoto 8 discussed bone formation mechanisms according to the histopathological findings of their bone forming pleomorphic adenoma case. In their report, the bone tissue was formed in the so-called stromal tissue and was surrounded by stromal fibrocytes and parenchymal epithelial cells, while no myxochondroid or chondral tissue was evident in the surrounding tissue. They discussed how the histopathological features suggested the possibility of stromal metaplasia of undifferentiated mesemcymal cells to osteoblast. Furthermore, Shigeishi et al. 3 have discussed their case with bone formation, and concluded the possibility of endochondral ossification according to the histopathological features of bone tissue formed within areas of chondral tissue. Arai et al. 2 discussed how the origin of bone-forming cells took place in the metaplasia of the true-stromal undifferentiated cells.

There are two theories in the origin of the bone-forming cells osteoblast and osteocytes: one from modified myoepithelial cells, and other from undifferentiated mesemchymal cells of true stromal tissue, including the possibility that one of the metaplastic factors was neoplastic cells producing BMP. Therefore, we sought to determine the origin of the bone forming cells in our present case using immunohistochemical technique with S-100 protein as a marker of myoepithelial cells, and Runx2 as a marker of bone forming cells. S-100 protein is a well-known marker of modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells of pleomorphic adenoma. Since there have been no report regarding the relationship between the modified myoepithelial cells and bone forming cells (osteoblasts and osteocytes) appearing in pleomorphic adenomas, we examined the relationship between the two.

In the present case, the bone forming cells showed positive immunohistochemical reaction to S-100. S-100 reaction appeared in the modified myoepithelial cells in the nests and spindle-shaped or oval-shaped modified myoepithelial cells of the stromal tissues. Furthermore, the cyto-proliferation of these modified myoepithelial cells continued to the bone forming cells, which reacted to Runx2, a well-known osteoblastic maker. Therefore, the results strongly suggest that the bone forming cells (osteoblasts and osteocytes) originated from the modified (neoplastic) myoepithelial cells. This means the metaplasia (trans-differentiation) took place between the epithelial and mesemchymal tissues, myoepithelium and bone forming cells (osteoblast and osteocytes), although there is supposedly no metaplasia between the epithelial cells and mesemchymal cells according to textbooks of pathology.

In addition, the bone tissue formed in the pleomorphic adenoma, revealed reversal line indicated by deeply-stained hematoxylin structure with osteoclasts and osteoblasts. This finding suggests that bone formation occurred over a long period of time.

In conclusion, our present study morphologically confirms that the origin of the bone forming cells in this case of pleomorphic adenoma was modified neoplastic myoepithelial cells. This finding strongly suggested that the trans-differentiation took place between the epithelial and mesemchymal tissues.

References

- 1.Eveson JW, Kusafuka K, Stenman G, Nagano T. Pleomorphic adenoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai Y, Sakuma Y, Yokozawa S, Uchida M, Fujita H, Nonaka H. A case of pleomorphic adenoma with remarkable bone formation. Jpn J Oral Surg. 2003;49:272–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigeishi H, Hayashi K, Takata T, Kuniyasu H, Ishikawa T, Yasui W. Pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland with extensive bone formation. Pathol Int. 2001;51:883–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thackray AC, Lucas RB. Tumors of the major salivary glands. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institure of Pathology; 1983. pp. 16–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe T, Shimizu T, Kou H, Okafuji N, Kurihara S, Kawakami T. A case of pleomorphic adenoma with bone formation. J Matsumoto Dent Univ Soc (Matsumoto Shigaku) 2006;32:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamakawa H, Takarada M, Ito C, Tabioka H. Bone-forming pleomorphic adenoma of the upper lip: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1471–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KC, Chan JK, Chong YW. Ossififying pleomorphic adenoma of the maxillary antrum. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:50–52. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100118596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeda Y, Yamamoto H. Stromal bone formation in pleomorphic adenoma of minor salivary gland origin. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1996;38:102–104. doi: 10.2334/josnusd1959.38.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yates PO, Paget GE. A mixed tumor of salivary gland showing bone formation, with a histochemical study of the tumor mucoids. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:881–888. doi: 10.1002/path.1700640419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]