Abstract

The mechanism by which prostaglandin synthase converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin G2, creating five new chiral centers in the process, is still incompletely understood. The first radical intermediate has been characterized by EPR spectroscopy but subsequent proposed intermediates have not succumbed to detection. We report the synthesis of 7-thiaarachidonic acid designed to stabilize one of the proposed radical intermediates, which may allow its detection.

Prostaglandin H synthase (PGHS, also called cyclooxygenase) catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGG2 through a radical cascade that is initiated via hydrogen atom abstraction from the C13 position of the substrate by an active site tyrosyl radical (Figure 1).1–5 The resulting radical intermediate I is then proposed to react with molecular oxygen to form peroxy radical II.6 A 5-exo trig cyclization onto the C8-C9 double bond leads to formation of intermediate III, followed by a second 5-exo trig cyclization to produce the 2.2.1 bicyclic intermediate IV. This radical is proposed to undergo a second reaction with oxygen to generate the peroxy radical intermediate V, which is converted to PGG2 by abstraction of a hydrogen atom from tyrosine, thereby regenerating the active form of the enzyme.6,7

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism for the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2. With the exception of radical I, no spectroscopic evidence is currently available for any of the proposed intermediates.

Under anaerobic conditions, the initially formed radical intermediate I has been characterized as a pentadienyl radical in PGHS-2.8–10 Experimental observation of subsequent radicals requires the presence of molecular oxygen as a co-substrate, but under aerobic conditions no radical intermediates are observed. Therefore the proposed carbon centered radicals II–V are not present in observable concentrations during aerobic turnover. In order to observe these radical intermediates, the rate determining step would have to be altered by either mutagenesis of the enzyme or modification of the substrate.

A primary kinetic isotope effect observed when tritium was incorporated at the C13 position6 indicates that the initial hydrogen atom abstraction is at least partially rate limiting. This is corroborated by computational studies, which have concluded that the formation of intermediates IV and V require similar activation energies as the hydrogen atom abstraction from C13.11,12 This implies that stabilizing either intermediate III or IV could cause a shift in the rate determining step for the reaction and allow detection of these intermediates.

Stabilization of carbon-centered radicals generated during enzyme catalysis can be achieved in a number of ways.13 Resonance delocalization using an adjacent π-system has been frequently used.13–18 An alternative approach involves incorporation of a sulfur atom adjacent to the radical site. This approach has been successfully used by Frey and co-workers to investigate the reaction mechanism of lysine 2,3-aminomutase.19,20

In that study the stabilization provided by the sulfur atom was estimated as ∼ 9 kcal/mol. The substantial stabilization of an α-sulfide radical over an alkyl radical has also been used in reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) processes to retard the rate of polymerization reactions.21–23

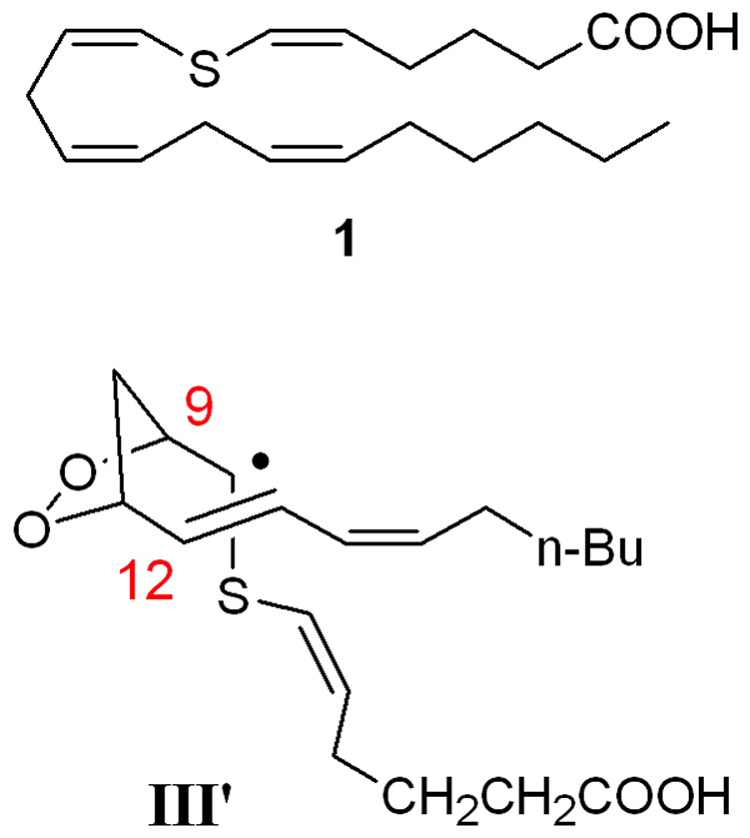

On the basis of these predicted thermodynamic stabilities and the previously calculated barriers for conversion of III to V we embarked on the preparation of 7-thiaarachidonic acid 1 (Figure 2). It was envisioned that if 7-thiaarachidonic acid were accepted by the enzyme, the proposed reaction mechanism would lead to the generation of radical intermediate III’, which would be stabilized by the adjacent sulfur atom and the possibly also by additional resonance stabilization involving the C5-C6 alkene. Previous studies have shown that 7-thiaarachidonic acid is a reversible inhibitor of PGHS-1.24 Inhibition of the PGHS-2 isozyme, for which the pentadienyl radical I has been characterized experimentally, has not been investigated. The PGHS-2 active site is larger and is more tolerant to alteration. For instance, acetylation of Ser530 of PGHS-1 by aspirin abolishes all catalytic activity whereas acetylation of the corresponding Ser516 in PGHS-2 does not prevent substrate binding and hydrogen atom abstraction from C13.25–29 Similar differences between the two isozymes have also been reported for site directed mutants of active site residues.27,30,31

Figure 2.

Structure of the synthetic target 7-thiaarachidonic acid 1 and the stabilized intermediate radical III’.

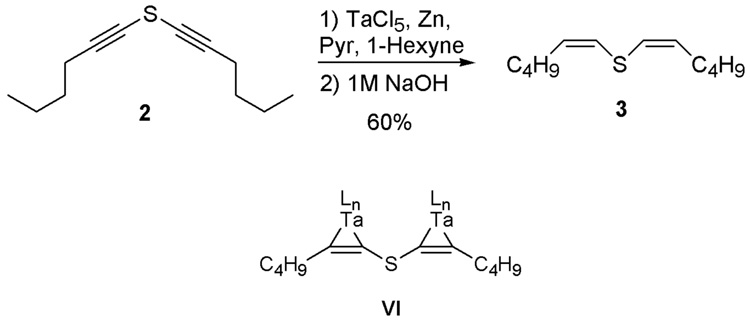

The synthetic challenge for 7-thiaarachidonic acid lies in the bis(Z-alkenyl)sulfide functionality in a molecule with two additional non-conjugated Z-alkenes. The synthesis of 7-thiaarachidonic acid has been previously reported in the mid 1980s in 17 steps.24 With the development in the intervening time of alternative methodologies, we elected to use a different synthetic route to the target compound. The most direct approach for the synthesis of the bis(Z-alkenyl)sulfide moiety is the stereoselective reduction of a bis(alkynyl)sulfide. Although to the best of our knowledge the reduction of a bis(alkynyl)sulfide has not been reported, several methods exist for reduction of a 1-alkynylsulfide. Using bis(hexynyl)sulfide 2 as a model system, several of these reduction conditions were screened. DIBAL-H reduction of the diyne was accomplished in moderate yield (55 %), but the E/Z selectivity was poor (1:1). Hydrogenation conditions previously reported for the reduction of 1-alkynylsulfides or 1-alkynylsulfoxides were also explored. However, Lindlar’s catalyst32 and Wilkinson’s catalyst33 did not produce the reduced product in appreciable yield. Finally, alkynyl sulfide reduction utilizing a stoichiometric amount of tantalum chloride and zinc metal was attempted.34 This reaction yielded the reduced bis(hexenyl)sulfide in 60% yield with very good stereocontrol as only the (Z,Z)-isomer was observed by ¹H and 13C NMR spectroscopy.

The tantalum-promoted stereoselective reduction is believed to proceed through initial formation of a low-valent tantalum species.35 Addition of the alkyne then generates a metallacyclopropene intermediate VI (Figure 3). The formation of such tantalum-η²-alkyne complexes has been demonstrated by ¹H and 13C NMR spectroscopy as well as x-ray crystallography.36,37 These air-sensitive intermediates can be hydrolyzed under basic conditions to yield the alkene, generally in good yield.

Figure 3.

Test substrate 2 for the stereoselective reduction of bisalkynylsulfides. The metallocyclopropene VI has been proposed as an intermediate in the tantalum catalyzed reduction.

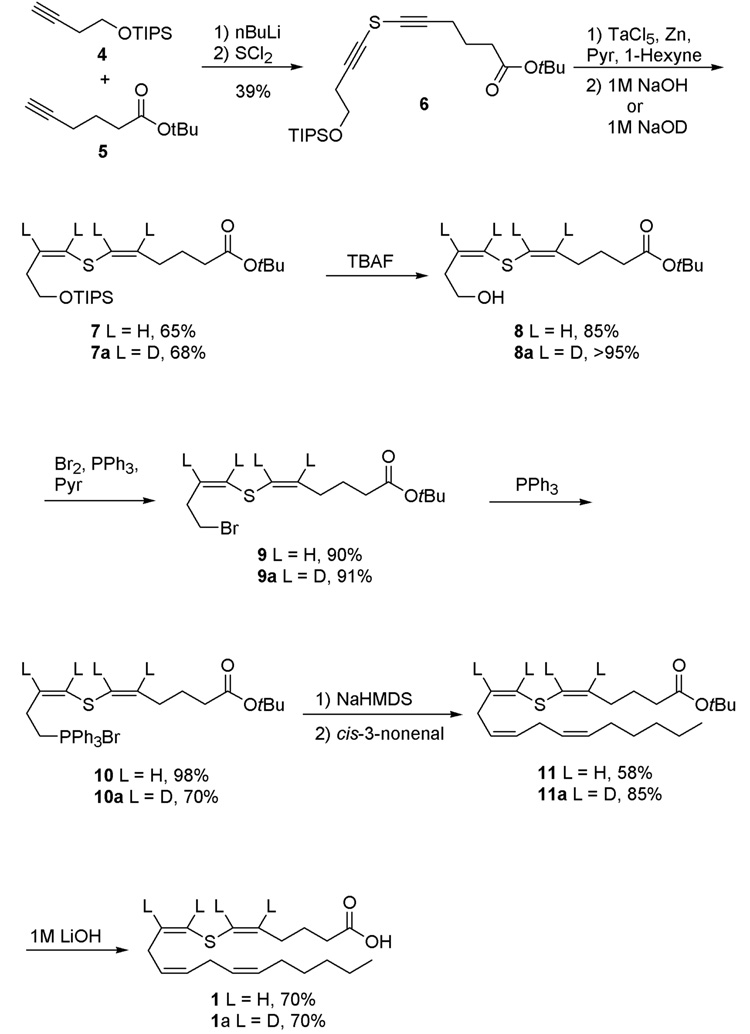

The low-valent tantalum reduction was attempted next on a more functionalized and asymmetric bis(alkynyl)sulfide. Treatment of alkynes 4 and 5 with n-butyllithium followed by slow addition of sulfur dichloride yielded the unsymmetric bis(alkynyl)sulfide 6 (Figure 4).38–40 Sulfide 6 was subjected to the tantalum-mediated reaction conditions resulting in formation of the bis(alkenyl)sulfide 7 in 65% yield and excellent stereoselectivity as only the Z,Z-isomer was detected by ¹H NMR spectroscopy. Interestingly, the reaction required the presence of a terminal hexyne in order to afford reproducible yields of the product. This requirement was discovered serendipitously because the initial attempt at reduction of 6 was conducted with substrate that still contained some 4. Subsequent reactions with pure 6 were unsuccessful unless 1-hexyne was added. Previous experiments have demonstrated that alkynylsulfides react faster than terminal alkynes with low-valent tantalum metal.41 Thus, the role of 1-hexyne in the reaction is not understood.

Figure 4.

Synthetic scheme for the preparation of 7-thia-arachidonic acid and its deuterium-labeled analogs.

The synthesis of 7-thiaarachidonic acid was completed as depicted in Figure 4. Deprotection of 7 with a 1.0 M solution of tetrabutylammonium fluoride afforded alcohol 8 in good yield. This alcohol was reacted with triphenylphosphine and bromine to produce bromide 9, which required rapid chromatographic purification as the compound was unstable to silica gel. Heating of the bromide with triphenylphosphine afforded phosphonium salt 10.

cis-3-Nonenal was synthesized by oxidation of cis-nonenol with Dess-Martin periodinane in quantitative yield.42 A Wittig reaction between phosphonium salt 10 and cis-3-nonenal under Z-selective conditions43,44 yielded tert-butyl thiaarachidonate 11, which was deprotected with a 1.0 M aqueous solution of lithium hydroxide and DME (1:2, v/v). The resulting 7-thiaarachidonic acid was purified by HPLC and isolated as a single isomer. The ¹H NMR spectrum of the compound was consistent with the spectrum reported by Corey and co-workers.24

One advantage of the tantalum pentachloride reduction is the facile incorporation of deuterium at the C5-C9 alkene positions, which is advantageous for EPR characterization of any substrate based radicals that may be formed with PGHS or human lipoxygenases that also use arachidonic acid as substrate for radical based transformations.45,46 The reaction is believed to proceed by basic hydrolysis of a metallocyclopropene intermediate. This step is consistent with the observation that quenching the reaction with a basic solution of deuterium oxide results in deuterium incorporation at both alkene positions for 1,2-disubstituted alkynes.35,41 To test whether this labeling strategy could be extended to bis(alkynyl)sulfides, the reduction of 6 was repeated, but a 1.0 M solution of sodium deuteroxide in deuterium oxide was used during the hydrolysis step. The reaction proceeded in good yield and stereocontrol. Based on ¹H NMR integration, the bis(alkenyl)sulfide 7a contained 97% deuterium at each alkene position. The remaining synthetic steps were identical to the synthetic route for the 7-thiaarachidonic acid. Deprotection with tetrabutylammonium fluoride yielded alcohol 8a, which was halogenated to form bromide 9a. Treatment with triphenylphosphine yielded phosphonium salt 10a. A Wittig reaction then afforded t-butyl 7-thia(5,6,8,9-²H4)arachidonate 11a in good yield. Final deprotection yielded the desired 7-thia(5,6,8,9-²H4)arachidonic acid 1a, which was purified by HPLC to afford the final compound as a single isomer.

In summary, we have developed a new synthetic route to 7-thiaarachidonic acid that marks an improvement over the previously reported route. Our unoptimized synthesis of the target compound was completed in only seven linear steps and allowed the rapid and convenient preparation of deuterium labeled analogs. EPR studies of the interaction of these compounds with PGHS-2 and human lipoxygenases are currently ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship to CMM from the American Heart Association (#0310006Z) and by the National Institutes of Health (GM44911).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and spectral characterization of all synthetic compounds.

References

- Karthein R, Dietz R, Nastainczyk W, Ruf HH. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;171:313. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AL, Hsi LC, Kulmacz RJ, Palmer G, Smith WL. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:5085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimokawa T, Kulmacz RJ, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:20073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Donk WA, Tsai AL, Kulmacz RJ. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15451. doi: 10.1021/bi026938h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2239. doi: 10.1021/cr000068x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:5336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Kulmacz RJ, Tsai AL. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8499. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AL, Kulmacz RJ, Palmer G. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Okeley NM, Tsai AL, Wu G, Kulmacz RJ, van der Donk WA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3609. doi: 10.1021/ja015599x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Okeley NM, Tsai AL, Wu G, Kulmacz RJ, van der Donk WA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10785. doi: 10.1021/ja026880u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg ML, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM, van der Donk WA, Tsai AL. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:3297. [Google Scholar]

- Silva PJ, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts. 2003;110:345. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:705. doi: 10.1021/cr980059c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson OT, Reed GH, Frey PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9764. [Google Scholar]

- Abend A, Bandarian V, Reed GH, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6250. doi: 10.1021/bi992963k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson OT, Reed GH, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7773. doi: 10.1021/bi0104569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Booker S, Lieder KW, Bandarian V, Reed GH, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9561. doi: 10.1021/bi000658p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Donk WA, Gerfen GJ, Stubbe J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4252. [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Lieder KW, Reed GH, Frey PA. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10532. doi: 10.1021/bi00033a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Bandarian V, Reed GH, Frey PA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;387:281. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnajjar MS, Zhang XM, Franz JA, Bordwell FG. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:4976. [Google Scholar]

- Coote ML. Macromolecules. 2004;37:5023. [Google Scholar]

- Coote ML, Henry DJ. Macromolecules. 2005;38:1415. [Google Scholar]

- Corey EJ, Cashman JR, Eckrich TM, Corey DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:713. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman MJ, Turk J, Shornick LP. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:21438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte M, Laneuville O, Ji C, DeWitt DL, Smith WL. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini JA, O'Neill GP, Bayly C, Vickers PJ. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:33. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Brash AR. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AL, Palmer G, Wu G, Peng S, Okeley NM, van der Donk WA, Kulmacz RJ. jbc. 2002;277:38311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuresson ED, Lakkides KM, Rieke CJ, Sun Y, Wingerd BA, Micielli R, Mulichak AM, Malkowski MG, Garavito RM, Smith WL. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Boeglin WE, Prusakiewicz JJ, Rowlinson SW, Marnett LJ, Samel N, Brash AR. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beccalli EM, Marchesini A, Pilati T. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:12697. [Google Scholar]

- Maezaki N, Izumi M, Yuyama S, Sawamoto H, Iwata C, Tanaka T. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:7927. [Google Scholar]

- Takai K, Miyai J, Kataoka Y, Utimoto K. Organometallics. 1990;9:3030. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Takai K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. Tetrahedron Letters. 1990;31:365. [Google Scholar]

- Hierso JC, Etienne M. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2000:839. [Google Scholar]

- Oshiki T, Tanaka K, Yamada J, Ishiyama T, Kataoka Y, Mashima K, Tani K, Takai K. Organometallics. 2003;22:464. [Google Scholar]

- Verboom W, Schoufs M, Meijer J, Verkruijsse HD, Brandsma L. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 1978;97:244. [Google Scholar]

- Ruecker C, Fritz H. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1988;26:1103. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KD, Wenzler DL, Matzger AJ. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2195. doi: 10.1021/ol034266x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Takai K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1615. [Google Scholar]

- Wavrin L, Viala J. Synthesis. 2002:326. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R, Chaykovsky M, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;28:1128. [Google Scholar]

- Bestmann HJ, Stransky W, Vostrowsky O. Chem. Ber. 1976;109:1694. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley CM, van der Donk WA. Chem. Commun. 2003:2843. doi: 10.1039/b311008g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash AR. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:23679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.