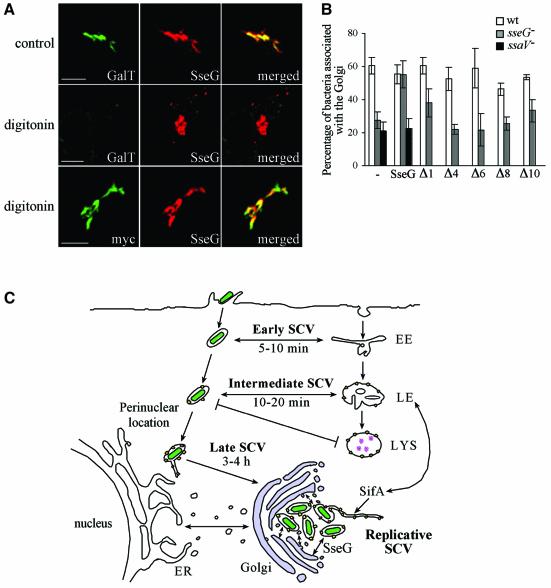

Fig. 7. Topology of SseG and functional activity of mutant polypeptides. (A) HeLa cells expressing myc::SseG were permeabilized with Triton X-100 (control) or digitonin and labelled with antibodies against myc, SseG or a luminal epitope of human galactosyltransferase (GalT). Scale bars correspond to 5 µm. (B) HeLa cells expressing wild-type or mutant myc::SseG polypeptides were infected for 10 h with GFP-expressing wild-type, ssaV or sseG mutant S.typhimurium. Cells were labelled with anti-myc and anti-giantin antibodies, and the level of bacterial association with the Golgi network was determined in both transfected and untransfected cells. Values represent means of three independent experiments and the standard deviations from the mean are shown. (C) Model of SCV trafficking in relation to localization within epithelial cells. Following host cell invasion, development of the early and intermediate SCV proceeds by progressive and selective interactions with compartments of the endocytic pathway (LAMP1 and cathepsin D are shown as yellow and pink symbols, respectively), as bacteria (green) migrate to a perinuclear location. This leads to the formation of the late SCV. The translocation of the SPI-2 TTSS effector SifA is required for recruitment of lgp-containing vesicles and the formation of Sifs, while SseG localizes SCVs to the Golgi network. As a consequence of this, the replicative phase of development can begin through acquisition of nutrients that enable bacterial replication, and membrane which encloses the growing population of intracellular bacteria. EE, early endosome; LE, late endosome; LYS, lysosome.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official

government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you've safely

connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.