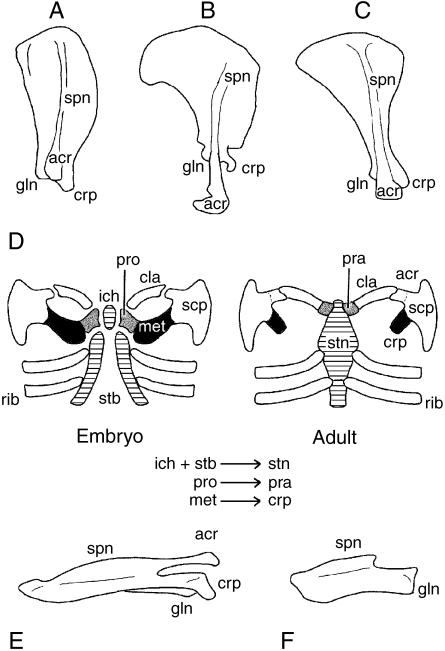

Fig. 6.

Therian scapula morphology and pectoral apparatus development. Adult (right) scapulae of (A) Canis, (B) Priodontes and (C) Mus in lateral view, demonstrating the morphological variation of this element. (D) Early during skeletogenesis the cellular condensations (membranous skeleton) giving rise to the pectoral apparatus include a median unpaired pars chondralis interclaviculae and bilateral coracoid–scapular plates, clavicular condensations, sternal bands and rib primordia. The bulk of the coracoid–scapular plate gives rise to the scapula, although a rudiment homologous with the procoracoid joins with the cranialmost portion of the coalescing sternal bands and pars chondralis interclaviculae to form the manubrium sterni. In addition, procoracoid may give rise to vestiges adjacent to the clavicular–sternal contact (the praeclavia). The portion of the coracoid–scapular plate homologous with the metacoracoid gives rise to the coracoid process and, at least in some eutherians, the acromion and part of the glenoid. Dorsal view of adult (left) scapula in Mus (E) wildtype and (F) undulated (Pax1 deficient) mutant (see text for details). Abbreviations: acr (acromion), cla (clavicle), cpr (coracoid process), gln (glenoid), ich (pars chondralis interclaviculae), met (metacoracoid), pra (praeclavium/suprasternal), pro (procoracoid), rib (rib), scp (scapula), spn (scapular spine), stb (sternal band), stn (sternum). Source for images: (A,B) modified from Flower (1876); (C,F,G) modified from Timmons et al. (1994), reproduced with permission from The Company of Biologists Ltd; (D) reprinted from Functional Morphology in Vertebrates, vol. 1, M. Klima, ‘Development of the shoulder girdle and sternum in mammals’, pp. 81–83 (1985).