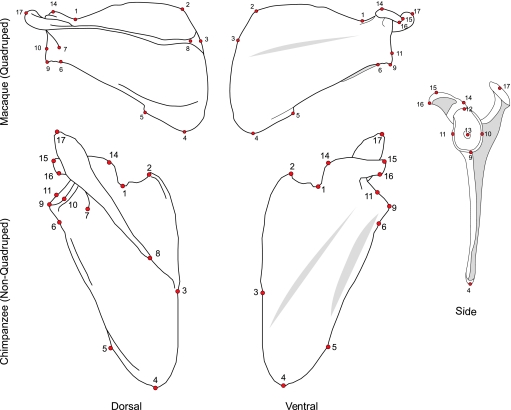

Fig. 1.

The scapula of a typical committed terrestrial quadruped (top, macaque) and an arboreal suspensory non-quadruped (bottom, chimpanzee) in dorsal and ventral view. The side view of a generalized primate scapula is shown on the far right. The typical quadrupedal scapula is longer from vertebral border to glenoid and shorter from superior to inferior angles. In non-quadrupeds such as apes and ateline monkeys this pattern is largely reversed. Note the differences in the shape of the blade, and the orientation and size of the spine that discriminate the extremes of these two groups. Location of landmarks are shown on both specimens: (1) suprascapular notch; (2) superior angle; (3) point on the vertebral margin where the long axis of the scapular spine and the vertebral border meet; (4) inferior angle; (5) teres major fossa; (6) infraglenoid tubercle; (7) spinoglenoid notch; (8) medial extent of the trapezius attachment along the scapular spine; (9) inferior-most point on glenoid fossa; (10) greatest width of the glenoid fossa (lateral); (11) greatest width of the glenoid fossa (medial); (12) superior-most point on glenoid fossa; (13) shallowest point (maximal curvature) of the glenoid fossa; (14) coracoid prominence; (15) distal-most tip of the coracoid process (superior); (16) distal-most tip of the coracoid process (inferior); (17) distal-most point of the acromion.