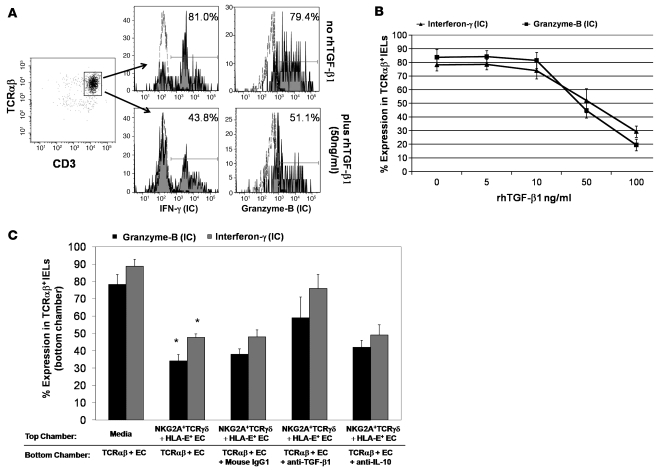

Figure 6. Suppression by CD3+TCRγδ+ NKG2A+ IELs is mediated by TGF-β1 secretion.

(A) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing percentage of CD3+TCRαβ IELs expressing intracellular IFN-γ (left) and granzyme B (right) in cocultures of CD3+TCRαβ IELs with ESA+ ECs were stimulated with rhIL-15 in the presence (bottom row) or absence (top row) of rhTGF-β1. (B) Percentage (mean ± SEM) of CD3+TCRαβ IELs expressing intracellular IFN-γ and granzyme B in cocultures of CD3+TCRαβ IELs with ESA+ ECs, in the presence of rhIL-15 to which different concentrations of rhTGF-β1 were added. Data shown are from 3 independent experiments. (C) Percentage (mean ± SEM) of CD3+TCRαβ+ IELs expressing intracellular IFN-γ and granzyme B in cocultures of CD3+TCRαβ+ IELs with ESA+ ECs, in the bottom chamber of a diffusion chamber system. When CD3+TCRγδ+NKG2A+ IELs with HLA-E+ ECs (from an ACD patient) were added to the top chamber, a significant decrease (*) in the percentage of CD3+TCRαβ IELs expressing intracellular IFN-γ (P = 0.006) and granzyme B (P = 0.003) was seen. However, inhibition of intracellular IFN-γ and granzyme B expression by CD3+TCRαβ IELs in the bottom chamber was blocked when 1 μg/ml of anti-human TGF-β1 antibody was added to the bottom chamber. This led to an increase in the percentage of CD3+TCRαβ+ IELs expressing intracellular IFN-γ by 28.0% ± 4.1% and granzyme B by 21.2% ± 9.3%, compared with cultures with mouse IgG1 (control). Addition of anti-human IL-10 did not block the suppressive effect of CD3+TCRγδ+NKG2A+ IELs; data shown from 4 independent experiments (P values determined by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test).