Abstract

Chemoperception in invertebrates is mediated by a family of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). To date nothing is known about the molecular mechanisms of chemoperception in coleopteran species. Recently the genome of Tribolium castaneum was sequenced for use as a model species for the Coleoptera. Using blast searches analyses of the T. castaneum genome with previously predicted amino acid sequences of insect chemoreceptor genes, a putative chemoreceptor family consisting of 62 gustatory receptors (Grs) and 26 olfactory receptors (Ors) was identified. The receptors have seven transmembrane domains (7TMs) and all belong to the GPCR receptor family. The expression of the T. castaneum chemoreceptor genes was investigated using quantification real- time RT-PCR and in situ whole mount RT-PCR analysis in the antennae, mouth parts, and prolegs of the adults and larvae. All of the predicted TcasGrs were expressed in the labium, maxillae, and prolegs of the adults but TcasGr13, 19, 28, 47, 62, 98, and 61 were not expressed in the prolegs. The TcasOrs were localized only in the antennae and not in any of the beetles gustatory organs with one exception; the TcasOr16 (like DmelOr83b), which was localized in the antennae, labium, and prolegs of the beetles. A group of six TcasGrs that presents a lineage with the sugar receptors subfamily in Drosophila melanogaster were localized in the lacinia of the Tribolium larvae. TcasGr1, 3, and 39, presented an ortholog to CO2 receptors in D. melanogaster and Anopheles gambiae was recorded. Low expression of almost all of the predicted chemoreceptor genes was observed in the head tissues that contain the brains and suboesophageal ganglion (SOG). These findings demonstrate the identification of a chemoreceptor family in Tribolium, which is evolutionarily related to other insect species.

Introduction

In living animals the chemical senses are important to detect various environmental chemical informations. The insect gustatory and olfactory systems play important roles in development and reproduction (the mate partner or an oviposition site) as well as in searching for host plants [1]. Insects are covered with chemosensory structures known as sensilla, were sensory neurons for olfactory stimuli and taste are located. Chemosensory sensilla are present on the antennae, mouth parts, legs, wings and the ovipositor [2]. Most of the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) are located on the antennae; whereas the gustatory neurons are present on the mouth parts and the legs [2]. In vertebrates, chemosensation is mediated by a large family of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) of the rhodopsin-related receptor superfamily, which are known as odorant receptors [3]. Receptors that belong to the GPCR families T2R and T1R mediate the sensing of sweet and bitter tastes and are known as gustatory receptors (Gr) in vertebrates. The vertebrate chemosensory receptor superfamily is evolutionarily distant from the invertebrate chemosensory receptor family [3].

Genome analysis of Drosophila melanogaster genome elucidated the presence of 62 olfactory receptors (Or), which are encoded by 60 genes, and 68 gustatory receptors (Gr), which are also encoded by 60 genes [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. From the genome of Anopheles gambiae 79 olfactory receptors and 76 gustatory receptors were identified [10]. The genome of Apis mellifera encoded 170 Or and 10 Gr receptor genes [11] and Bombyx mori genome encoded 41 olfactory receptors [12], 17 of which appear to be orthologs of Helicoverpa virescens [13], [14]. Recently the genome of Aedes aegypti was found to contains genes for 131 Or receptors, and 88 gustatory receptors [15]. In the last few years much had been made in understanding the molecular and neurological mechanism of insect chemoperception, especially in D. melanogaster, including the fact that the number of glomerulus's is almost in a ratio of 1:1 to Or receptors [16], [1]. Using this information it is now possible to predict the number of olfactory receptors in different insect species.

The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum is an insect pest that belongs to the Tenebrionidae family within the order Coleoptera. It presents the most destructive species of stored product insects. It attacks stored grain products, dried pet food, dried flowers, chocolate, nuts, seeds, and even dried museum specimens [17]. Tribolium beetles are also considered as secondary pests, where they infest previously damaged and addicted grains [18]. Recently, the genome of T. castaneum has been sequenced to 7-fold coverage using a whole genome shotgun approach and assembled using the HGSC's assembly engine Atlas (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/projects/tribolium/).

The present paper describes the molecular characterization of a chemoreceptor family in T. castaneum. The receptor gene sequences provide novel information to study their molecular evolution in relation to other insect chemoreceptor gene family. The molecular data have allowed studies on the expression of receptor gene transcripts in various tissues of the beetles to be conducted, which may help to elucidate their physiological significance.

Results

Prediction of T. castaneum chemoreceptors

Using blast searches of the genome sequence of Tribolium castaneum, a family of 88 receptors was identified (Table 1 and Figure S1A). All of the predicted proteins were found to share a common structure of seven transmembrane domains, belonging to the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Figure S1B). Sixty two of the genes showed sequence similarity to the gustatory receptor families of Drosophila melanogaster [5], Anopheles gambiae [10], Apis mellifera [11], and Aedes aegypti (unpublished data) with 6 to 13% identity (Figure S1C). Most receptors of the insect Gr receptors also found to share a signature motif with a PKFSAGFFDIDRTLLFSIFGAITTYLIILIQF amino acid sequences in the putative seventh transmembrane domain at the C-terminus (Figure S2).

Table 1. List of all identified chemoreceptors genes in T. castaneum .

| Number | Gene bank accession Number | Gene proposed name | Map position | Number of introns | Size (amino acids) |

| 1 | AM292322 | TcasGr10 | 7 | 3 | 373 |

| 2 | AM292323 | TcasGr2 | 5 | 6 | 586 |

| 3 | AM292324 | TcasGr38 | 7 | 2 | 398 |

| 4 | AM292325 | TcasGr4 | 2 | 1 | 309 |

| 5 | AM292326 | TcasGr5 | 7 | 3 | 522 |

| 6 | AM292327 | TcasGr6 | 4 | 2 | 387 |

| 7 | AM292328 | TcasGr7 | 5 | 7 | 429 |

| 8 | AM292329 | TcasGr104 | 7 | 3 | 379 |

| 9 | AM292330 | TcasGr9 | 5 | 5 | 408 |

| 10 | AM292331 | TcasGr1 | 7 | 1 | 437 |

| 11 | AM292332 | TcasGr11 | 7 | 2 | 344 |

| 12 | AM292333 | TcasGr12 | Un | 2 | 316 |

| 13 | AM292334 | TcasGr13 | Un | 2 | 390 |

| 14 | AM292335 | TcasGr14 | 7 | 1 | 374 |

| 15 | AM292336 | TcasGr15 | 5 | 5 | 455 |

| 16 | AM292337 | TcasGr16 | 10 | 2 | 452 |

| 17 | AM292338 | TcasGr17 | 10 | 3 | 372 |

| 18 | AM292339 | TcasGr150 | 10 | 2 | 387 |

| 19 | AM292340 | TcasGr19 | 7 | 2 | 355 |

| 20 | AM292341 | TcasGr20 | 6 | 4 | 393 |

| 21 | AM292342 | TcasGr21 | 5 | 4 | 385 |

| 22 | AM292343 | TcasGr22 | 10 | 1 | 301 |

| 23 | AM292344 | TcasGr79 | Un | 4 | 291 |

| 24 | AM292345 | TcasGr123 | 7 | 1 | 384 |

| 25 | AM292346 | TcasGr25 | Un | 0 | 314 |

| 26 | AM292347 | TcasGr26 | 4 | 2 | 387 |

| 27 | AM292348 | TcasGr27 | 6 | 4 | 346 |

| 28 | AM292349 | TcasGr28 | 5 | 3 | 250 |

| 29 | AM292350 | TcasGr29 | 9 | 7 | 429 |

| 30 | AM292351 | TcasGr30 | 5 | 6 | 394 |

| 31 | AM292352 | TcasGr31 | 5 | 4 | 250 |

| 32 | AM292353 | TcasGr32 | 7 | 4 | 651 |

| 33 | AM292354 | TcasGr47 | 6 | 1 | 321 |

| 34 | AM292355 | TcasGr34 | 6 | 1 | 324 |

| 35 | AM292356 | TcasGr35 | 6 | 1 | 251 |

| 36 | AM292357 | TcasGr105 | 7 | 1 | 355 |

| 37 | AM292358 | TcasGr37 | 7 | 3 | 331 |

| 38 | AM292359 | TcasGr3 | 5 | 2 | 436 |

| 39 | AM292360 | TcasGr39 | 7 | 1 | 437 |

| 40 | AM292361 | TcasGr40 | 5 | 1 | 373 |

| 41 | AM292362 | TcasGr41 | Un | 1 | 398 |

| 42 | AM292363 | TcasGr71 | 6 | 5 | 347 |

| 43 | AM292364 | TcasGr43 | 8 | 2 | 353 |

| 44 | AM292365 | TcasGr44 | 2 | 1 | 313 |

| 45 | AM292366 | TcasGr45 | 4 | 3 | 379 |

| 46 | AM292367 | TcasGr46 | 7 | 7 | 1451 |

| 47 | AM292368 | TcasGr33 | 4 | 2 | 387 |

| 48 | AM292369 | TcasGr48 | Un | 2 | 408 |

| 49 | AM292370 | TcasGr49 | 7 | 1 | 418 |

| 50 | AM292371 | TcasGr50 | 7 | 3 | 350 |

| 51 | AM292372 | TcasGr51 | 7 | 5 | 771 |

| 52 | AM292373 | TcasGr54 | 7 | 2 | 360 |

| 53 | AM292374 | TcasGr62 | 7 | 4 | 659 |

| 54 | AM292375 | TcasGr52 | 4 | 3 | 311 |

| 55 | AM292376 | TcasGr125 | 7 | 3 | 402 |

| 56 | AM292377 | TcasGr56 | 5 | 4 | 358 |

| 57 | AM292378 | TcasGr57 | 2 | 3 | 387 |

| 58 | AM292379 | TcasGr98 | 4 | 4 | 376 |

| 59 | AM292380 | TcasGr59 | Un | 0 | 489 |

| 60 | AM292381 | TcasGr60 | 10 | 4 | 364 |

| 61 | AM292382 | TcasOr61 | 7 | 7 | 670 |

| 62 | AM292383 | TcasOr53 | 7 | 3 | 319 |

| 1 | AM689931 | TcasOr1 | 7 | 2 | 353 |

| 2 | AM689904 | TcasOr2 | 7 | 0 | 314 |

| 3 | AM689905 | TcasOr3 | 4 | 2 | 413 |

| 4 | AM689906 | TcasOr4 | 2 | 0 | 378 |

| 5 | AM689907 | TcasOr5 | 2 | 0 | 299 |

| 6 | AM689908 | TcasOr6 | 8 | 5 | 475 |

| 7 | AM689909 | TcasOr7 | 2 | 1 | 311 |

| 8 | AM689910 | TcasOr63 | 9 | 4 | 383 |

| 9 | AM689911 | TcasOr9 | 9 | 1 | 294 |

| 10 | AM689912 | TcasOr10 | 8 | 1 | 330 |

| 11 | AM689913 | TcasOr11 | 8 | 0 | 332 |

| 12 | AM689914 | TcasOr12 | 2 | 2 | 374 |

| 13 | AM689915 | TcasOr13 | 6 | 5 | 405 |

| 14 | AM689916 | TcasOr56 | 10 | 5 | 433 |

| 15 | AM689917 | TcasOr15 | 10 | 1 | 340 |

| 16 | AM689918 | TcasOr16 | 6 | 4 | 475 |

| 17 | AM689919 | TcasOr17 | 8 | 3 | 243 |

| 18 | AM689920 | TcasOr18 | 8 | 1 | 410 |

| 19 | AM689921 | TcasOr19 | 9 | 0 | 331 |

| 20 | AM689922 | TcasOr20 | 10 | 1 | 386 |

| 21 | AM689923 | TcasOr21 | 8 | 0 | 240 |

| 22 | AM689924 | TcasOr22 | 9 | 1 | 382 |

| 23 | AM689925 | TcasOr23 | 9 | 4 | 360 |

| 24 | AM689926 | TcasOr24 | 9 | 0 | 343 |

| 25 | AM689927 | TcasOr25 | 9 | 6 | 791 |

| 26 | AM689928 | TcasOr26 | 9 | 0 | 338 |

Un = Chromosome LGUn

Another 26 identified genes showed sequence similarity to the olfactory receptor families of D. melanogaster [4], [6], A. gambiae [10], A. mellifera [11], Bombyx mori [12], Helicoverpa virescens [13], [14], and A. aegypti [15] with about 15% homology (Figure S1D). The receptor gene family was code named T. castaneum olfactory receptor family (TcasOr).

Genome analyses

The TcasGr receptors amino acid sequence lengths are extremely diverse. They range from 250 aa (TcasGr28) to 1451 aa in TcasGr46 (Table 1). The mean length of the TcasGrs is about 412 aa. Within the predicted TcasGr receptors four groups consisting of more than ten members were found to have at least 1-4 introns (Table 1). Another three groups with two to four members were found to contain 5-7 introns, and in one group of two receptors no introns were found. The TcasOr receptors also varied in their aa lengths (240 aa for TcasOr21 to 791 aa for TcasOr25). The mean length of the TcasOr receptors was about 374 aa (Table 1). Eight of the predicted TcasOr receptors contained no introns. Seven receptors had one intron each and two groups, each consists of three receptors had two and five introns each, respectively. One group of three receptors had four introns each (Table 1), TcasOr17 had three introns, and the TcasOr25 had six introns. 64 of the T. castaneum chemoreceptor genes were found to contain a conserved intron near the carboxyl terminus (Table 1).

24 receptor genes including 22 TcasGr genes and two TcasOr genes were located on chromosome 7 (Table 1 and Figure S3). The evolutionary relationships of these genes, based on their amino acid sequences, showed that they arrange in five subfamilies consisting of eight, two, four, seven and two proteins (Figure S3). A weak bootstrap value supported the evolutionary relationships between the different families. The TcasGr19 gene does not belong to any of the subfamilies. 7, 7, 11, 8, 7, 9, and 8 receptor genes of TcasGr and Or receptors were localized on the chromosomes two, four, five, six, eight, nine and ten, respectively (Table 1). Seven of the predicted TcasGr genes were localized on the Un chromosome. There was not suggestion that any of the predicted genes was a pseudogene, as none were interrupted by a stop codon nor were any frame shift mutations detected (Table 1). GPCRHMM protein analysis of all the putative T. castaneum chemoreceptors family showed that only the TcasGr19 and TcasGr40 are true GPCR proteins (Table 2 and S2). Within chemoreceptors from other insect species, AmelGr5 from, A. mellifera is also a true GPCR protein (Table 2 and S2).

Table 2. List of insect chemoreceptors that belong to the GPCR superfamily based on GPCRHMM analysis.

| Sequence identifier | Global | Local | Prediction | |

| Proposed name | Accession number | |||

| TcasGr19 | (AM292340) | 60.36 | 75.14 | GPCR |

| TcasGr40 | (AM292361) | 3.34 | 15.90 | GPCR |

| AmelGr5 | 6.61 | 15.71 | GPCR | |

For other details see Figure S2.

Phylogenetic analysis of T. castaneum chemoreceptor family

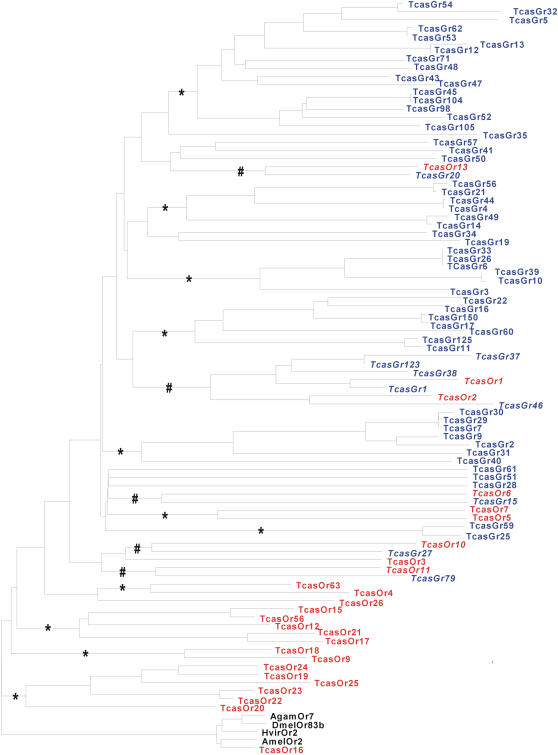

The entire chemoreceptor family of T. castaneum consists of 88 putative receptors (Figure S1A). Alignment analysis of the T. castaneum chemoreceptor gene family (TcasGr and TcasOr) indicated that the family members share a high degree of sequence divergence (Figure S1C, S1D). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the presence of five distinct lineages of TcasGr and TcasOr receptor subfamilies (Figure 1). One lineage containing seven chemoreceptors (TcasGr37, 123, 38, 1, and 46, and TcasOr1 and 2) was identified. Another four lineages each consisting of two receptors, TcasOr13 and TcasGr20, TcasOr6 and TcasGr15, TcasOr10 and TcasGr27, and TcasOr11 and TcasGr79, respectively, (Figure 1) were found. The TcasGr receptors alone represented six lineages of proteins, and the TcasOr receptors formed five lineages of proteins (Figure 1). The TcasOr16 displayed a lineage with its homologs from other insect species (DmelOr83b, AmelOr2, HvirOr2, and AgamOr7) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Neighbor joining tree of T. castaneum chemoreceptor genes family.

The T. castaneum putative chemoreceptor genes (TcasGr and TcasOr) are indicated to the right. The corrected distance tree was rooted by declaring the TcasOr16 and its homologs (DmelOr83b, AmelOr2, AgamOr7, and HvirOr2) as outgroup, based on their position at the base of the insect Or family in the phylogenetic analysis of [11]. Receptors that represent lineages are indicated in bold and italics, and the supported bootstrap value (>50%) is indicated with #. * represents lineages of either TcasGr or TcasOr receptors supported with a bootstrap value of >50%. TcasGr are written in blue letters, TcasOr are written in red, and the members of TcasOr16 outgroup are written in black. The amino acid sequences alignment was carried out using CLUSTAL X [47]. The neighbour joining tree was produced using the PHYLIP package [48] and based on the consensus of 1000 bootstrap replicates. Tree drawing was performed as corrected-distance cladogram with the help of TreeView 1.6.6. program.

Phylogenetic analysis of the insect gustatory receptor (Gr) family

The genome of T. castaneum encoded at least 62 Gr genes compared to 60 Gr genes in D. melanogaster [9], 52 Gr genes in A. gambiae, [10], 10 Gr genes in A. mellifera [11], and 88 Gr genes in A. aegypti (unpublished data). The 62 T. castaneum Gr genes showed thirteen lineages in a phylogenetic analysis of all known insect Grs (Figure S4). Based on the role of DmelGr5a as a trehalose receptor, six of the T. castaneum Gr receptors, TcasGr2, TcasGr7, TcasGr9, TcasGr29, TcasGr30, and TcasGr31, were clustered confidently with eight sugar receptors each of D. melanogaster and A. gambiae, nine sugar receptor candidates of A. aegypti (unpublished data), and two (Gr1 and 2) of A. mellifera [9], [19], [11]. An ortholog for the highly conserved lineage of the DmelGr21a, DmelGr63a, and AgamGr22-24 proteins was also identified. The TcasGr1 and TcasGr39 clustered confidently with DmelGr21a, AgamGr22, and AaegGr21b, respectively. The TcasGr3 represented an ortholog with AgamGr24, DmelGr63a, and AaegGr63a (Figure S4). TcasGr6, TcasGr26 and TcasGr33 clustered confidently with the AaegGr21a and AgamGr23 proteins. None of the AmelGrs clustered within these orthologs (Figure S4). There was a weak bootstrap value supporting the lineage of TcasGr10, TcasGr46, TcasGr38, TcasGr62, and TcasGr123 as being orthologs to AmelGr3, DmelGr43a, AgamGr25 and AaegGr43a (Figure S4). The remaining TcasGr lineages had no apparent orthologs to any other known insect Gr lineage. Within the TcasGr receptors, alternative splicing relationships between TcasGr2 and TcasGr9, TcasGr7, TcasGr29 and TcasGr30, TcasGr6, TcasGr26 and TcasGr33, and TcasGr17 and TcasGr150 existed (data not shown).

Phylogenetic analysis of insect olfactory receptor (Or) families

Phylogenetic analysis of the proteins encoded by the 26 TcasOr receptor genes, along with the Ors of D. melanogaster [5], [6], A. gambiae [10], A. mellifera [11], H. virescens [13], [14], B. mori [12], and A. aegypti [15] showed that they comprised six lineages (Figure S5). Three lineages consisted of four, two, and five TcasOr receptors, respectively, and had no apparent orthologs in any other insect species identified (Figure S5). One subfamily was extraordinarily expanded to 18 Or receptors including TcasOr9 and TcasOr18 together with 16 members of AmelOr (AmelOr142-148 and AmelOr150-158) as orthologs (Figure S5). Another subfamily represents the only orthologs between TcasOr and the lepidopteran Ors, where the TcasOr13 forms a strong lineage with BmorOr13, HvirOr4, HvirOr1, and HvirOr5. No relationships between TcasOr and any Or receptors of flies was detected with one exception: TcasOr16, which was show to be an ortholog with DmelOr83b, AgamOr7, AmelOr2, AaegOr2, BomrOr2 and BmorOr2a (Figure S5). Alignment analysis also showed that TcasOr16 had a 75% identity in its amino acid sequences to DmelOr83b (data not shown).

Quantification real time RT-PCR analysis

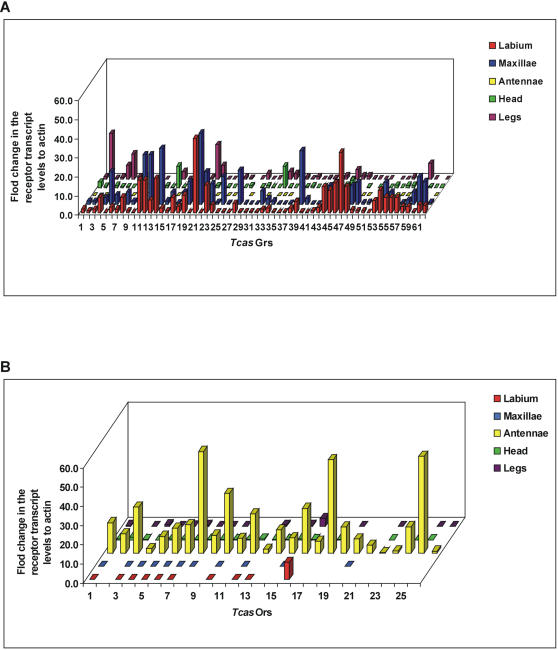

Tissue-specific expression patterns of the T. castaneum chemoreceptor genes were determined by quantitative (Q) real time RT-PCR analysis. The amplification efficiency of each primer set was validated; standard curves (5× serial dilutions starting with 2 ng/µl RNA concentration) yielded regression lines with r2 values >0.97 and slopes ranging from 3.07–3.20 (a slope of 3.13 indicates 100% amplification efficiency). Q-RT-PCR analysis revealed that the 62 TcasGr genes were expressed as a single transcript in T. castaneum labium and maxillae tissues (gustatory organs of the mouth parts) (Figure 2A). 55 of the putative TcasGr genes were also expressed in the femur, tibia, and tarsus of the adult T. castaneum prolegs (Figure 2A); while seven of the predicted genes were not expressed in the adult prolegs (Figure 2A). The receptors genes were also expressed to a low level in the head tissues [brain- suboesophageal ganglion (SOG)].

Figure 2. Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis of T. castaneum chemoreceptor genes family.

It shows the relative transcription levels of (A) TcasGr receptor genes, and (B) TcasOr receptor genes in the labium, maxillae, antennae, heads (without gustatory and olfactory organs), and prolegs of adult T. castaneum. The genes are encoded on X axon with numbers as described in Table 1. The data on Y axon represented mean±SD normalized relative to the actin related protein transcript levels. All samples were run in triplicate and the entire assay was performed twice for each biological pool.

For the TcasOr receptor genes the amplification efficiency of the respective primer sets was validated as described above and the r2 values were >0.98 and slopes ranged from 3.04–3.12 (a slope of 3.08 indicates 100% amplification efficiency). All the TcasOr receptors were expressed as a single copy in the adult antennae (olfactory organ) (Figure 2B). The TcasOr16 was also expressed in the labium and the prolegs of adult beetles (gustatory tissues) (Figure 2B). Expression of the TcasOr receptor genes in head tissues (brain-SOG) was also recorded.

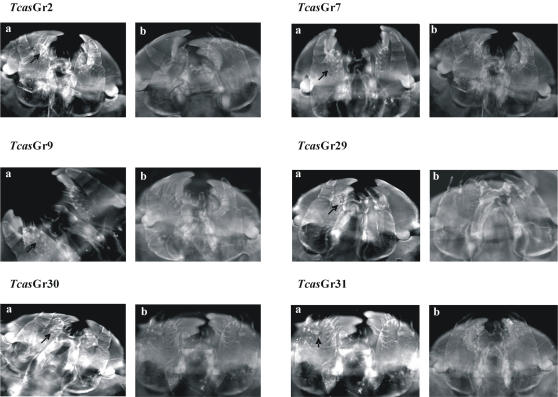

Tissues specific localization using in situ whole mount RT-PCR analysis

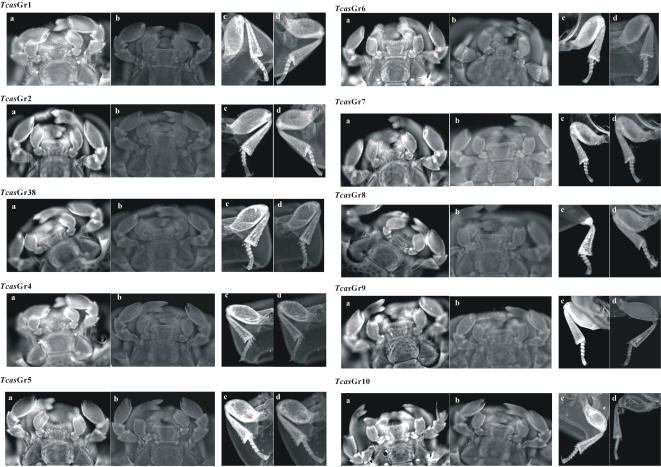

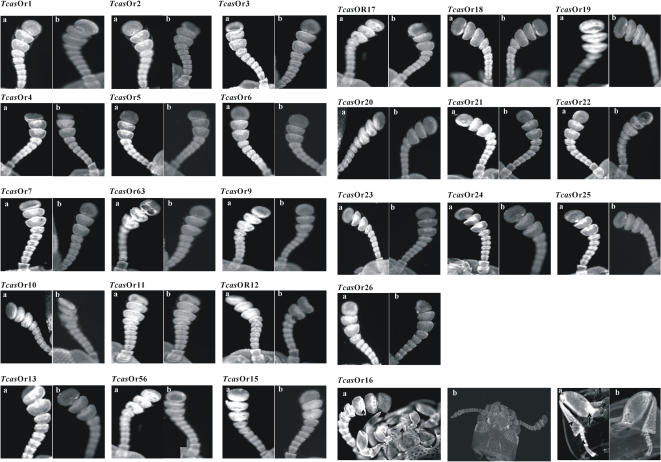

Whole mount in situ RT-PCR analysis showed that all the putative TcasGr receptor genes were localized in the labium and maxillae of adult Tribolium (Figures 3 and S6). 55 of the TcasGr were also localized in the femur, tibia, and tarsus of the adult prolegs (Figures 3 and S6). During the last instar larvae, TcasGr2, 7, 9, 29, 30, and 31, which are candidates for sugar receptors, as shown in the phylogenetic analysis (Figure S4), were localized in the lacinia of the maxillae (Figure 4). 25 members of TcasOr genes were localized in the antennae of adult beetles (Figure 5), and the TcasOr16 was localized not only in the antennae but also in the labium, maxillae, and prolegs of the beetles (Figure 5). The negative controls using the sense RNA probes did not show any positive signal in the tissues studied (Figures 3, 4, 5, and S6).

Figure 3. Tissue specific localization of the T. castaneum Gr receptors using whole-mount in situ RT-PCR analysis.

The TcasGr1, 2, 38, and 4–10 candidates were localized in the labium and maxillae of the adult beetles, but also in the femur, tibia and tarsus of the prolegs. (a) shows the expression of the TcasGr receptors in the labium and maxillae of adult mouth parts. (c) shows the expression of the TcasGr receptors in the femur, tibia, and tarsus of adult prolegs. (b) and (d) show the sense negative controls. The TcasGr mRNAs were labeled using Dig 11-dUTP (Roche) and visualized by fluorescence in situ RT-PCR analysis using HNPP/Fast Red TR (Roche).

Figure 4. Tissue specific localization of T. castaneum Gr sugar receptor candidates in the head of larval using whole-mount in situ RT-PCR analysis.

The receptors were localized in the lacina of the maxillae. (a) shows the antisense mRNA expression. (b) shows the sense negative controls. For other details see Figure 3.

Figure 5. Tissue specific localization of the T. castaneum Or receptor genes in the antennae of adult beetles using whole-mount in situ RT-PCR.

(a) shows the antisense mRNA expression. (b) shows the sense negative controls. The last line shows the expression of the TcasOr16 receptor (homolog to DmelOr83b) in the antennae, mouth parts (labium and maxillae), and in the prolegs (femur, tibia, and tarsus) of adult beetles. For other details see Figure 3.

Discussion

Taken together the data in this study characterizes a chemoreceptor family in T. castaneum, which consists of 88 receptors. 62 are gustatory receptors (TcasGrs), which are expressed mainly in gustatory organs of the beetle's mouth parts and the prolegs. Another 26 are olfactory receptors (TcasOrs) that are localized only in the antenna; while the TcasOr16 (homolog to DmelOr83b) was localized in gustatory and olfactory organs of Tribolium. In previous studies, members of DmelGr receptors were localized in the labellum, pharynx, legs, and anterior wing margins of D. melanogaster [5], and the DmelOrs were localized mainly in the antennae of the fly [6]. In A. aegypti 64 Or receptors were expressed in the antennae of the mosquitos [10]. In B. mori all of the 41 BmorOr genes were localized in the antennae [12].

In this paper I have showed that T. castaneum has at least 62 gustatory receptors and 26 olfactory receptors. However, since conservation of these gene families was extremely low (6–15%), the number of chemoreceptors might be underestimated. This phenomenal was previously recorded in other insect species: For example [5] first characterized a family of 42 chemoreceptors genes, 19 of them being gustatory receptors. Later [7] and [8] extended the family to 54 and 56, respectively. Afterwards [9] extended the chemoreceptor family in Drosophila to 130 receptors of 68 Grs and 62 Ors. The Tribolium genome has at least 200 Gr receptors and 250 Or receptors, where many of them are pseudogenes (Hugh Robertson; personal communication). This means that the chemoreceptor family in the beetles may well be added to in future.

Alignment analysis showed that the TcasGr receptors shared a signature motif of 32 amino acids. The data agreed well with [8], who showed that 23 of the DmelGr and 33 of the DmelOr share a 33 amino acids motif. Within the T. castaneum novel chemoreceptor genes family none of the predicted receptor genes appear to be pseudogene. Within the D. melanogaster chemoreceptor family only DmelOr98p is a pseudogene [9]. The olfactory receptors family of A. mellifera included 7 pseudogenes [11]. In A. aegypti 21 of the identified Ors are pseudogene [15]. 46 of the genes have a conserved intron near the carboxyl terminus.

In Drosophila half of the predicted Gr genes had a single intron in the 7TM region [5], [7]. In this study most of the T. castaneum chemoreceptors can be arranged into large clusters up to 8 genes that have 0–4 introns. 64 memebrs of T. castaneum chemoreceptors had one intron localized in the 7TM region. Some of the Grs in Drosophila are encoded by alternatively spliced genes [5], and in A. gambiae 5 Grs are also alternative spliced genes [4]. The Tribolium Gr family included also alternative spliced genes. The Drosophila chemoreceptors are distributed on 5 chromosomes and presented in clusters of more than 3 genes [4]. The olfacory receptors in A. gambiae are distributed over three chromosomes, arranged mostly in pairs, triples or large clusters up to 9 genes [10]. The T. castaneum chemoreceptors are distributed on nine chromosomes mostly arranged in clusters of 7 genes or in large clusters up to 24 genes. This pattern of lineage-specific subfamily may reflect the physiological, biological, and ecological importance of these receptors.

Insect chemoreceptors belonged to the GPCR class A, the bovine rhodopsin like family [20], where the second extracellular loop (E2 loop) has extensive contact with many extracellular regions as well as with the ligand retinal. Length variations, especially in the E2 loop and in terminal fragments, could contribute to the functional specificity between the ligands and the G-proteins [21]. Abnormal length configuration in the E2 loop may also play a negative regulatory role in receptor activation, where it stabilizes the inactive state of the receptor [22]. The T. castaneum chemoreceptor proteins have an E2 loop with a mean of 36 amino acids. The shortest E2 loops (12 amino acids) were found in TcasGr7, 29, 30 and 60, whereas the longest E2 loop (87 amino acids) was found in TcasGr49. The data is in line with [23], who showed that the invertebrate Or receptors have a relatively long E2 loop with 47 amino acids on average.

Insect Ors do not belong to the GPCR family [24]. Recent studies using GPCRHMM analysis also strongly rejects the claim that the arthropod-specific Or receptors are GPCRs [25]. A detailed analysis showed that these receptor sequences, including D. melanogaster Gr and A. gambiae Gr, are very different from other GPCR proteins [25]. GPCRHMM protein analysis shows that the TcasGr19, TcasGr40, and AmelGr5 are true GPCR protein. It seems that these proteins form a superfamily of environment-sensing receptors, which have little in common with odorant receptors in the mammals, and probably have a different membrane topology [25].

Phylogenetic analysis of the Gr families reveals similar pattern of largely lineage-specific gene subfamily. There are 13 orthologous pairs of Grs shared by the T. castaneum, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, and A. aegypti species, but only two of them are conserved (DmelGr5a ortholog and the DmelGr21a, DmelGr63a, and AgamGr22-24 ortholog), suggesting that these receptors might be sufficiently conserved to recognize the same ligands in different species. An ortholog which is represented by six receptor genes in T. castaneum was evolutionary related to the sugar receptors candidates of D. melanogaster (DmelGr5a subfamily) [19], [9], A. gambiae [10], A. aegypti (unpublished data), and AmelGr1 and AmelGr2 of A. mellifera [11]. Another ortholog of TcasGr1, TcasGr39, and TcasGr3 is related to DmelGr21a, DmelGr63a, and AgamGr22-24 receptor gene subfamily. None of the AmelGrs clustered within these orthologs. Recently in [26], it was shown that the DmelGr21a and DmelGr63a and their homologs in A. gambiae (AgamGr22 and AgamGr24) are true carbon dioxide receptors. Whether, TcasGr1, TcasGr39, and TcasGr3 are CO2 receptors is still unknown.

One exception to the rapid evolution can be seen in the expressed DmelOr83b receptor and its orthologous in other insect species, including AmelOr2, AgamOr7, HvirOr2, BmorOr2, BmorOr2a, and AaegOr7 [11], [10], [27], [12], [15], where they expressed in olfactory and gustatory organs. DmelOr83b has an unusual function, acting as “courier” supporting the functions of other Or receptors in the dendritic membrane of olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) [24], [28], [29]. DmelOr83b and its ortholog AgamOr7 were also broadly expressed throughout olfactory and gustatory tissues of Drosophila and Anopheles [24], [30]. Absence of DmelOr83b in Drosophila limited the activity in neurons of other olfactory receptors. This gravely reduced the physiological and behavioral responses of adult Drosophila to a wide range of odorants, altered adult metabolism, enhanced stress resistance and extended their life span [31]. In T. castaneum the TcasOr16 is an ortholog to DmelOr83b. It was expressed in gustatory and olfactory organs of the beetles and shared 75% of its' amino acid sequences identity with DmelOr83b. Whether the TcasOr16 receptor is also necessary for the mediation of other receptors functions, and is essential for the development of the beetles, has still to be elucidated.

The organs of smell (olfactory sensilla) in Coleoptera species lie not only on the antennae but also on the wings and the legs [32], while taste sensilla are concentrated on the maxillae and labial palpi and other mouthparts and are often found on tibiae or tarsi of the front legs. In insect the ORNs had been shown to detect odor quality, quantity, and temporal changes in odor concentration [33], [34], [35]. The antenna in Drosophila has about 1200 ORNs and 120 on the maxillary palp [36], [37]. On the antennae of the mosquito A. gambiae about 1500-1600 ORNs are present [38]. In Tenebrionidae species Tenebrio molitor the antenna bear 2861 ORNs distributed on antennal segments 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, and 5 with 1338, 705, 455, 208, 118, 34, and 3 sensilla, respectively, [39]. 564 of these sensilla probably have olfactory and or gustatory functions and belonged to thin-walled peg sensilla. Other type of sensilla such as thick-walled peg organs, grooved peg organs, and smooth-surfaced peg organs sensilla are located on the antennal segments 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, and 4, respectively, and have olfactory functions. The larvae of T. castaneum have 21 sensilla organized into 1 trichoid, 8 styloconic, 1 placoid, 9 campaniform, and 2 coeloconic sensilla on the antennae [40].

All of the TcasOr genes were localized on the antennal segments 9-4. Q real time RT-PCR analyses showed also that 25 of the TcasOr genes were expressed in the antennae. The TcasOr16 (homolog to DmelOr83b) was localized in the antennae, maxillae, labium, and prolegs of the beetles. Low expression was recorded within the brain-SOG tissues. I suggest that the TcasOr16 was mainly expressed in the flat-tipped peg sensilla, chaetica sensillum or in thin-walled peg sensilla. Such sensilla were previously suggested to have gustatory functions in T. molitor (Tenebrionidae) [39]. The Drosophila olfactory sensilla were mainly located on the antennae and maxillary palp, in each of which one or few olfactory receptor genes are expressed [6], [41], [4].

Q-RT-PCR analysis revealed that the 62 TcasGr genes were expressed as a single transcript in T. castaneum labium and maxillae tissues (gustatory organs of the mouth parts). Low expression levels of the genes were found in the head tissues (brain-SOG). In situ whole mount RT-PCR analyses also showed that the Gr receptors were localized in the maxillae and labium of the beetles. Within the Teneprionidae Cryphaeus cornutus taste sensilla are located on the maxillae and labial palp. There are 12 sensilla on the maxillary palp and 28 on the labial palp [42]. In coleopteran species the number of sensilla on the palps ranges from 4 to 12. In Drosophila the taste sensilla are located on the labial palp, proboscis, labral and cibarial sense organ on the pharynx, where their neurons projects axons to the SOG of the brain, processing gustatory information [6], [41], [4]. A few chemosensory neurons were located on the legs of Drosophila, legs bristles, tibia and tarsi, on the anterior wing margin, and on the abdominal vaginal plate. 57 TcasGr genes were expressed and localized in the proleg tissues RNA (trochanter, femur and Tarsi). In beetle legs there are a group of ORNs located at the end of each trochanter, sometimes on the femur, commonly on the tibia, and sometimes on the tibial spine and on the tarsi [32]. The number of the ORNs on the six legs varied from 49- 341. For example, Tenebrio molitor has 66 chemoreceptor sensilla on the legs, 145 on the elytra and 462 on the wings, while Uloma impressa has 80 chemoreceptor sensilla on the legs, 119 on the elytra and 361 olfactory sensilla on the wings [32]. Expression studies and tissue specific localization of the predicted TcasGr and TcasOr genes in the wings and other two pairs of legs have not yet been carried out.

An approximate 1:1 ratio of Or genes to glomeruli was found in the neurobiological organization of the olfactory system in several different insects such as D. melanogaster [43], [44], A. mellifera [11], B. mori [12]. A. gambiae has 61- 60 glomeruli [45] while the number of Or receptors is 79 [10]. Expression analyses in the larval and adult olfactory organs also reveal that the ratio of odorant receptors to antennal glomeruli was not one to one in A. aegypti [15]. In this study 26 olfactory receptors were predicted. The total number of olfactory sensilla within the Tenebrionidae species is in general more than 26. Taking this into account the family of olfactory receptors in T. castaneum might be an underestimate. Future studies to prove this theory may be interesting.

The results demonstrated here present a putative chemoreceptor family in T. castaneum, an insect species with biological and evolutionary history different from those for D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, B. mori, or A. mellifera. Knowledge of the genes structure, characterization of their expression, and their evolutionary relationship to other insect species are significant steps towards a deeper understanding of how chemical stimuli in Tribolium are perceived and processed. These results also open the way to the characterization of their homologs in other coleopteran species.

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics analyses

Known insect chemoreceptors sequences which had been submitted to GEN-BANK (National Center for Biotechnology Information) were used to search for similar genes in Tribolium castaneum genome sequences. The protein sequences were used to perform a TBLASTN [46] comparing a protein sequence against nucleotide database through two servers: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/seq/BlastGen/BlastGen.cgitaxid7070 and http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/projects/tribolium/. The predicted nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acid sequences using a variety of bioinformatic algorithms including the Baylor College of Medicine six frame translation server (http://searchlauncher.bcm.tmc.edu/seq-util/Options/sixframe.html/), the translate tool server at http://www.expasy.org/tools/dna.html/, and EMBOSS transeq server at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/emboss/transeq/. Prediction of intron/exon splice sites was carried out using the online servers http://deepc2.psi.iastate.edu/cgi-bin/sp.cgi/ and http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html. Transmembrane helix domain within the predicted proteins was done using TMHMM program; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/, Tm-pred program; http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html, and HMMTOP version 2.0 program; http://www.enzim.hu/hmmtop/html/submit.html/. The identified proteins were analyzed to GPCR structure using the GPCRHMM server (http://gpcrhmm.cgb.ki.se/tm.html/ ) [26]. The blast servers http://www.expasy.ch/tools/blast/ and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/Blast.cgi/ were used for comparison with other known protein sequences from different species. The servers http://www.soe.ucsc.edu/research/compbio/gpcr-subclass/, and http://pfam.janelia.org/hmmsearch.shtml/ were used to classify the predicted proteins into subfamily. Finally all of the chemoreceptor DNA sequences were amplified using PCR techniques for further study.

Beetles rearing

T. castaneum beetles were purchased from Biologische Bundesanstalt (BBA); Berlin, Germany, and were reared in glass containers provided with growing medium under constant conditions of 30°C and 70% relative humidity at L 16: D 8 hrs photoperiod.

Genomic DNA extraction

To amplify the complete receptor gene sequences of the putative chemoreceptors, genomic DNA of T. castaneum was extracted and used as a PCR template in the following manner: individual T. castaneum adults were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder. The powder was resuspended and the genomic DNA was extracted according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer of QIAamp® DNA Mini kit (50) (Qiagen GmbH). The extracted genomic DNA was later used as a template in PCR reactions to amplify the whole receptor gene sequences. The genomic DNA (100 ng/µl) was used as a template in combination with the specific TcasGr1-62/OrF1-26-TcasGrR1-62-OrR1-26) (Table S1A). The PCR program was 95°C for 3 min, followed by 10 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 45 sec decreasing by 1.0°C per cycle and 68°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 40–45°C for 45 sec, 68°C for 2 min, and a final extension step of 68°C for 10 min.

Cloning and sequencing

All of the amplified DNAs were eluted from low melting point agarose gel (Biozym Biotech, Oldendorf, Germany) using GFX™ purification kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany), and ligated into plasmids with the StrataClone™ PCR vector cloning kit supplied with StrataClone™ SoloPack competent cells (Stratagene) for amplification. Plasmid DNAs were later purified using QIAprep® Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen GmbH). The templates were sequenced by MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany).

Phylogenetic analysis

The D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, H. virescens, B. mori, and A. aegypti olfactory and gustatory receptor sequences were downloaded from the genomic DNA archive database at the national center for biotechnology information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/agtrace.html/). Alignment analysis of T. castaneum Gr and Or receptor deduced amino acid sequences were performed by means of AlignX server; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/ [47]. The corrected distance of tree was rooted by declaring the TcasOr16 and its homologs (DmelOr83b, AmelOr2, AgamOr7, and HvirOr2) as outgroup, based on their position at the base of the insect Or family in the phylogenetic analysis of [11]. The neighbour joining tree was produced using the PHYLIP package [48] and based on the consensus of 1000 bootstrap replicates. Tree drawing was performed as corrected-distance cladogram with the help of TreeView 1.6.6. program.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis

To investigate the expression of T. castaneum chemoreceptors in different tissues, total RNAs were extracted from two different biological pools of labium (gustatory tissue), maxillae (gustatory tissue), antennae (olfactory tissue), heads (from which olfactory and gustatory tissues had been removed but still included brain suboesophageal ganglion (SOG)), and prolegs of T. castaneum adults (N = 100 per biological pool). The total RNA was extracted using Invertebrate RNA Kit (Peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH) in combination with a DNase treatment (RNase-free DNase set; Qiagen) to eliminate potential genomic DNA contamination. After extraction, the RNA samples were stored at −80°C until use.

The expression of the T. castaneum chemoreceptors was performed using quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis. The Q-real time RT-PCR reactions were preformed in 20 µl reaction volume containing 10 µl of 2× FullVelocity™ SYBR® Green Q-RT-PCR master mix, 0.3 µl diluted reference dye, 0.05 µl StrataScript® RT/RNase block enzyme mixture (Stratagene), 1 µl pro primer (20 pmoL) (Table S1B), 2 µl RNA (2 ng/µl), and 5.65 µl DEPC H2O. To generate a relative standard curve, the endogenous protein T. castaneum actin (EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Data Base, accession number; XM_961644 was used. The actin primer nucleotide sequences were 5′-ATGTCGGCGACGCTAC-3′ as forward primer and 5′-GCTATACTGATACGGAC-3′ as reverse primer. With these primers a fragment of 224 bp was yielded and later used as a relative standard. Relative standard curves for the TcasGr and TcasOr receptors were generated with a series of five dilutions of the RNA from adult T. castaneum labium, maxillae, antennae, heads and prolegs, respectively. A dilution series of a standard sample (actin) was included within each RT-PCR run. Reactions were run in triplicate on MX3005P Real Time PCR System (Stratagene) using the following thermal cycling profiles of 50°C (30 min) and 95°C (5 min), followed by 40 steps of 95°C for 30 sec, 45–50°C for 1 min and 72°C for 30 sec. Afterwards, the PCR products were heated to 95°C for 30 sec, cooled to 45°C for 1 min and heated to 95°C for 30 sec to measure the dissociation curves. All assays were performed twice for each RNA biological pool to minimize variations due to sample handling.

The specificity of the different PCR amplification reactions was double checked using analysis of the dissociation curves for the T. castaneum chemoreceptor gene transcripts and their endogenous control, which showed a single melting peak. The different PCR products were later analyzed via gel electrophoresis, which proved the presence of a single band of the expected size for each chemoreceptor gene transcript. In all negative controls, no amplification of the fluorescent signal was detected, proving that there was no contamination with genomic DNA in the RNA samples

Whole-mount in situ RT-PCR analysis

The head tissues of T. castaneum adults, including the labium, maxillae, and antennae, the prolegs of adult beetles, and the heads of last instar larvae were dissected and immediately placed in fixative buffer (4% paraformaldehyde in DEPC-PBS buffer (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaH2PO4 )). After decolourization by incubation in H2O2 for 1 h. the tissues were dehydrated in a series of 30, 50, 70, 95, and 96% (v/v) ethanol/H2O followed by protein digestion using proteinase K solution (2 μg/ml) for 15 min. For other details see [49].

Supporting Information

Nucleotide sequences (5-3′) of the primers that were used in this study

(0.36 MB PDF)

Insect chemoreceptors that are not belong to the GPCR superfamily.

(0.09 MB DOC)

T. castaneum putative chemoreceptors gene family. (A) The deduced amino acid sequences from the cDNA of the T. castaeum gustatory (Gr) and olfactory receptors (Or). (B) Table showing the T. castaneum chemoreceptor names (accession numbers) and the predicted TM domain positions for each receptor using the GPCRHMM server; http://gpcrhmm.cgb.ki.se/. (C) Alignment analysis of the insect gustatory receptor superfamily including T. castaneum Gr, D. melanogaster Gr, A. gambiae Gr, A. mellifera Gr, and A. aegypti Gr using the http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/server. The gene names are given at the left and the amino acid positions are given at the right. (D) Alignment analysis of the insect olfactory receptor superfamily including the putative T. castaneum Or, D. melanogaster Or, A. gambiae Or, A. mellifera Or, H. virescens Or, B. mori Or, and A. aegypti Or7. For other details see (C).

(0.71 MB PDF)

The signature motif of the Gr receptors in insect species. Sequence alignments of the Gr gene families of T. castaneum, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, and A. aegypti revealed a common amino acid motif in the Gr sequences. The Gr sequences are marked to the left with their proposed gene name. The average similarity in the sequence motif was more than 50%. Alignment of the amino acid sequence was analyzed using CLC Free Workbench 3.2.2. software. The consensus alignment and the colouring of the conserved residues was asigned using ClustalX.

(0.88 MB PDF)

The molecular evolution of 24 chemoreceptor genes localized on chromosome seven of T. castaneum. The proposed gene names for the chemoreceptor are given to the right. The main lineages within the receptors are supported by bootstrap values >50% and are indicated with *. Only TcasGr19 does not belong to any of the orthologs within the tree. For other details see Figure S2.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Neighbor joining tree of the insect gustatory receptor superfamily. D. melanogaster (DmelGr), A. gambiae (AgamGr), A. mellifera (AmelGr), A. aegypti (AaegGr) (unpublished data), and T. castaneum Gr receptor gene sequences were used to draw the orthologous relationships between the gustatory receptors of the different insect species. Insect Gr receptors are indicated at the right. Receptors that represent lineages between different insect species are written in bold and italic. The supported bootstrap values (>50%) are denoted with #. The insect sugar receptor subfamily is shown in blue. The insect CO2 receptor subfamily is indicated in green. A weak bootstrap value (<50%) is indicated with a black square, and the appropriate orthologs are written in red. * represents lineages of only T. castaneum Gr receptor orthologs supported with a bootstrap value of >50%. For other details see Figure 1.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Neighbor joining tree of the insect olfactory receptor superfamily. Insect olfactory receptor genes (Or) are indicated to the right. The corrected distance tree was rooted by declaring the TcasOr16 and its homologs (DmelOr83b, AmelOr2, AgamOr7, BmorOr2, BmorOr2a, and HvirOr2) as outgroup. Receptors that represent lineages between different insect species are written in blue, and the supported bootstrap values (>50%) are denoted with #. * represents lineages of only T. castaneum Or receptor orthologs supported with a bootstrap value of >50%. For other details see Figure 1.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Tissue specific localization of the T. castaneum Gr receptors. The T. castaneum Gr11-62 were localized in the labium and maxillae of the adult beetles, and in the femur, tibia and tarsus of the larval prolegs. For other details see Figure 5.

(2.03 MB PDF)

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Prof. Dr. Monika Hilker (Free University of Berlin) for motivating discussion and suggestions for improvement the manuscript. I thank Prof. Dr. Klaus Hoffmann (University of Bayreuth) for critical reading of the manuscript in its preparation stage. I also thank the Department of Zoology, Free University of Berlin, Germany, for using the fluorescent microscope for the in situ RT-PCR experiments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The research was supported by the Free University of Berlin, Department of Applied Zoology/Animal Ecology.

References

- 1.Hallem EA, Dahanukar A, Carlson JR. Insect odour and taste receptors. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:113–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.051705.113646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Goes van Naters W, Carlson JR. Insects as chemosensors of humans and crops. Nature. 2006;444:302–307. doi: 10.1038/nature05403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bargmann CI. Comparative chemosensation from receptors to ecology. Nature. 2006;444:295–301. doi: 10.1038/nature05402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clyne PJ, Warr CG, Freeman MR, Lessing D, Kim JH, et al. A novel family of divergent seven-transmembrane proteins: candidate odorant receptors in Drosophila. Neuron. 1999;22:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clyne PJ, Warr CG, Carlson JR. Candidate taste receptors in Drosophila. Science. 2000;287:1830–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vosshall LB, Amerin H, Morozov PS, Rzhetsky A, Axel R. A spatial map of olfactory receptor expression in the Drosophila antenna. Cell. 1999;96:725–736. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunipace L, Meister S, McNealy C, Amrein H. Spatially restricted expression of candidate taste receptors in the Drosophila gustatory system. Curr Biol. 2001;11:822–835. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott K, Brady JR, Cravchik A, Morozov P, Rzhetsky A, et al. A chemosensory gene family encoding candidate gustatory and olfactory receptors in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;104:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson HM, Warr CG, Carlson JR. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14537–14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill CA, Fox AN, Pitts RJ, Kent LB, Tan PL, et al. G protein-coupled receptors in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:176–178. doi: 10.1126/science.1076196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson HM, Wanner KW. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 2006;16:1395–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.5057506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wanner KW, Anderson AR, Trowell SC, Theilmann DA, Robertson HM, et al. Female-biased expression of odorant receptor genes in the adult antennae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger J, Raming K, Dewer YM, Bette S, Conzelmann S, et al. A divergent gene family encoding candidate olfactory receptors of the moth Heliothis virescens. . Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:619–628. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieger J, Grosse-Wilde E, Gohl T, Dewer YM, Raming K, et al. Genes encoding candidate pheromone receptors in a moth (Heliothis virescens). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11845–11850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403052101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohbot J, Pitts RJ, Kwon HW, Rützler M, Robertson HM, et al. Molecular characterization of the Aedes aegypti odorant receptor gene family. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rützler M, Zwiebel LJ. Molecular biology of insect olfaction: recent progress and conceptual models. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2005;191:777–790. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong D, Pai A, Yan G. AFLP-based genetic linkage map for the red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum). J Heredity. 2004;95:53–61. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trematerra P, Sciaretta A, Tamasi E. Behavioural responses of Oryzaephilus surinamensis, Tribolium castaneum and Tribolium confusum to naturally and artificially damaged durum wheat kernels. Entomol Exp Appl. 2000;94:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chyb S, Dahanukar A, Wickens A, Carlson JR. Drosophila Gr5a encodes a taste receptor tuned to trehalose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14526–14530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135339100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Singhvi A, Kong P, Scott K. Taste representations in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2004;117:981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacquin-Joly E, Merlin C. Insect olfactory receptors: contributions of molecular biology to chemical ecology. J Chem Eco. 2004;30:2359–2397. doi: 10.1007/s10886-004-7941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otaki JM, Yamamoto H. Length analyses of Drosophila odorant receptors. J Theor Biol. 2003;223:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benton R, Sachse S, Minchink SW, Vosshall LB. Atypical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:0240–0257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wistrand M, Käll L, Sonnhammer ELL. A general model of G protein-coupled receptor sequences and its application to detect remote homologs. Protein Sci. 2006;15:509–521. doi: 10.1110/ps.051745906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones WD, Cayirlioglu P, Kadwo IG, Vosshall LB. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;445:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature05466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger J, Klink O, Mohl C, Raming K, Breer H. A candidate olfactory receptor subtype highly conserved across different insect orders. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2003;189:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, et al. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones WD, Nguyen TA, Kloss B, Lee KJ, Vosshall LB. Functional conservation of an insect odorant receptor gene across 250 million years of evolution. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R119–R121. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitts RJ, Fox AN, Zwiebel LJ. A highly conserved candidate chemoreceptor expressed in both olfactory and gustatory tissues in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5058–5063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Libert S, Zwiener J, Chu X, vanVoorhies W, Roman G, et al. Regulation of Drosophila life span by olfaction and food-derived odors. Science. 2007;315:1133–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1136610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micndoo NE. The olfactory sense of Coleoptera. Biol Bull. 1915;28:407–460. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinbockel T, Kaissling KE. Variability of olfactory receptor neuron responses of female silkmoths (Bombyx mori L.) to benzoic acid and (±)-linalool. J Insect Physiol. 1996;42:565–578. [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bruyne M, Clyne PJ, Carlson JR. Odor coding in a model olfactory organ: the Drosophila maxillary palp. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4520–4532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Bruyne M, Foster K, Carlson JR. Odor coding in the Drosophila antenna. Neuron. 2001;30:537–552. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stocker RF. The organization of the chemosensory system in Drosophila melanogaster: a review. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;275:3–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shanbhag S, Muller B, Steinbrecht A. Atlas of olfactory organs of Drosophila melanogaster. 1. Types, external organization, innervation and distribution of olfactory sensilla. Int J Insect Morphol Embryol. 1999;28:377–397. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu YT, van Loon JJA, Takken W, Meijerink J, Smid HM. Olfactory coding in antennal neurons of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Chem Sense. 2006;31:845–863. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harbach RE, Larson JR. Humidity behavior and the identification of hygroreceptors in the adult mealworm, Tenebrio molitor. J Insect Physiol. 1977;23:1121–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behan M, Ryan MF. Ultrastructure of antennal sensory receptors of Tribolium larvae (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Int J Insect Morphol Embryol. 1978;7:221–236. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Q, Chess A. Identification of candidate Drosophila olfactory receptors from genomic DNA sequence. Genomics. 1999;60:31–39. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alekseev MA, Sinitsina EE, Chaika SY. Sensory organs of the antennae and mouth parts of beetle larvae (Coleoptera). Entomol Rev. 2006;86:638–648. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Q, Yuan B, Chess A. Convergent projections of Drosophila olfactory neurons to specific glomeruli in the antennal lobe. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:780–785. doi: 10.1038/77680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vosshall LB, Wong AM, Axel R. An olfactory sensory map in the fly brain. Cell. 2000;102:147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghaninia M, Hannson BS, Ignell R. The antennal lobe of the african malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae-innervation and three-dimensional reconstruction. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2007;36:23–39. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeanmougin F, Thompson JD, Gouy M, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. Multiple sequence alignment with ClustalX. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:403–405. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Felsenstein J. Seattle, WA: Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdel-latief M, Hoffmann KH. The adipokinetic hormones in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda: cDNA cloning, quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis, and gene specific localization. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:999–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nucleotide sequences (5-3′) of the primers that were used in this study

(0.36 MB PDF)

Insect chemoreceptors that are not belong to the GPCR superfamily.

(0.09 MB DOC)

T. castaneum putative chemoreceptors gene family. (A) The deduced amino acid sequences from the cDNA of the T. castaeum gustatory (Gr) and olfactory receptors (Or). (B) Table showing the T. castaneum chemoreceptor names (accession numbers) and the predicted TM domain positions for each receptor using the GPCRHMM server; http://gpcrhmm.cgb.ki.se/. (C) Alignment analysis of the insect gustatory receptor superfamily including T. castaneum Gr, D. melanogaster Gr, A. gambiae Gr, A. mellifera Gr, and A. aegypti Gr using the http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/server. The gene names are given at the left and the amino acid positions are given at the right. (D) Alignment analysis of the insect olfactory receptor superfamily including the putative T. castaneum Or, D. melanogaster Or, A. gambiae Or, A. mellifera Or, H. virescens Or, B. mori Or, and A. aegypti Or7. For other details see (C).

(0.71 MB PDF)

The signature motif of the Gr receptors in insect species. Sequence alignments of the Gr gene families of T. castaneum, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. mellifera, and A. aegypti revealed a common amino acid motif in the Gr sequences. The Gr sequences are marked to the left with their proposed gene name. The average similarity in the sequence motif was more than 50%. Alignment of the amino acid sequence was analyzed using CLC Free Workbench 3.2.2. software. The consensus alignment and the colouring of the conserved residues was asigned using ClustalX.

(0.88 MB PDF)

The molecular evolution of 24 chemoreceptor genes localized on chromosome seven of T. castaneum. The proposed gene names for the chemoreceptor are given to the right. The main lineages within the receptors are supported by bootstrap values >50% and are indicated with *. Only TcasGr19 does not belong to any of the orthologs within the tree. For other details see Figure S2.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Neighbor joining tree of the insect gustatory receptor superfamily. D. melanogaster (DmelGr), A. gambiae (AgamGr), A. mellifera (AmelGr), A. aegypti (AaegGr) (unpublished data), and T. castaneum Gr receptor gene sequences were used to draw the orthologous relationships between the gustatory receptors of the different insect species. Insect Gr receptors are indicated at the right. Receptors that represent lineages between different insect species are written in bold and italic. The supported bootstrap values (>50%) are denoted with #. The insect sugar receptor subfamily is shown in blue. The insect CO2 receptor subfamily is indicated in green. A weak bootstrap value (<50%) is indicated with a black square, and the appropriate orthologs are written in red. * represents lineages of only T. castaneum Gr receptor orthologs supported with a bootstrap value of >50%. For other details see Figure 1.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Neighbor joining tree of the insect olfactory receptor superfamily. Insect olfactory receptor genes (Or) are indicated to the right. The corrected distance tree was rooted by declaring the TcasOr16 and its homologs (DmelOr83b, AmelOr2, AgamOr7, BmorOr2, BmorOr2a, and HvirOr2) as outgroup. Receptors that represent lineages between different insect species are written in blue, and the supported bootstrap values (>50%) are denoted with #. * represents lineages of only T. castaneum Or receptor orthologs supported with a bootstrap value of >50%. For other details see Figure 1.

(0.03 MB PDF)

Tissue specific localization of the T. castaneum Gr receptors. The T. castaneum Gr11-62 were localized in the labium and maxillae of the adult beetles, and in the femur, tibia and tarsus of the larval prolegs. For other details see Figure 5.

(2.03 MB PDF)