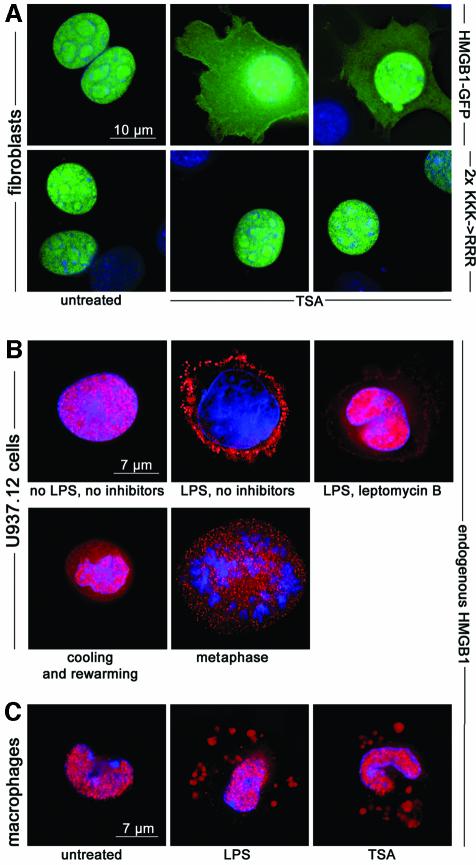

Fig. 4. HMGB1 moves to the cytoplasm following TSA treatment. (A) Exposure of mouse fibroblasts to 10 ng/ml TSA for 1 h causes a significant relocation of HMGB1–GFP to the cytoplasm; no vesicles are recognizable. The mutation of six lysines to arginines (2×KKK→RRR) prevents the cytoplasmic accumulation of HMGB1–GFP, even after TSA treatment. (B) U937.12 cells were cultured for 3 h with or without LPS or leptomycin B. Cells were then fixed and immunostained with anti-HMGB1 antibody (red). HMGB1 is exclusively nuclear in resting U937.12 cells, whereas it is predominantly vesicular in LPS-activated cells. Leptomycin blocks nuclear export, and consequently vesicular accumulation. A significant fraction of HMGB1 is contained in the cytoplasm and in vesicles in resting U937.12 cells that have been incubated 3 h at 4°C to promote passive diffusion of hypoacetylated HMGB1 to the cytoplasm and rewarmed to 37°C for 5 min to resume active transport (‘cooling and rewarming’). Likewise, a significant fraction of HMGB1 is contained in the cytoplasm and in vesicles when U937.12 cells enter M phase and free hypoacetylated HMGB1 into the cytoplasm after nuclear membrane breakdown (‘metaphase’). (C) Mouse peritoneal macrophages contain HMGB1 in the nucleus, but after stimulation with LPS, a fraction of HMGB1 is transferred to cytoplasmic vesicles. Incubation with TSA, but in the absence of LPS, also causes the transfer of HMGB1 to vesicles.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official

government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you've safely

connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.