Abstract

Numerous loci in host organisms are involved in parasite recognition, such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes in vertebrates or genes involved in gene-for-gene (GFG) relationships in plants. Diversity is commonly observed at such loci and at corresponding loci encoding antigenic molecules in parasites. Multilocus theoretical models of host–parasite coevolution predict that polymorphism is more likely than in single-locus interactions because recurrent coevolutionary cycles are sustained by indirect frequency-dependent selection as rare genotypes have a selective advantage. These cycles are stabilized by direct frequency-dependent selection, resulting from repeated reinfection of the same host by a parasite, a feature of most diseases. Here, it is shown that for realistically small costs of resistance and virulence, polycyclic disease and high autoinfection rates, stable polymorphism of all possible genotypes is obtained in parasite populations. Two types of epistatic interactions between loci tend to increase the parameter space in which stable polymorphism can occur with all possible host and parasite genotypes. In the parasite, the marginal cost of each additional virulence allele should increase, while in the host, the marginal cost of each additional resistance allele should decrease. It is therefore predicted that GFG polymorphism will be stable (and hence detectable) when there is partial complementation of avirulence genes in the parasite and of resistance genes in the host.

HOST–PARASITE interactions are recognized as a major evolutionary force producing biological diversity. Genetic variation for resistance reduces the probability that an individual parasite can infect an individual host (May and Anderson 1990) and conversely, genetic diversity at parasite recognition loci increases the range of potentially susceptible hosts. Spatial and temporal genetic polymorphism is commonly found in nature at loci involved in host–parasite recognition such as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in vertebrates (Apanius et al. 1997; Hill 2001) or genes involved in gene-for-gene (GFG) relationships, a common feature of plant–parasite interactions (Thrall et al. 2001; Laine 2004). In both the MHC and the GFG systems, hosts and parasites may have multiple interacting loci (Apanius et al. 1997; Hill 2001; Palomino et al. 2002). Interactions among several plant resistance (RES) genes and parasite avirulence (AVR) genes have been documented for numerous diseases, of which the best studied include barley powdery mildew (Jorgensen 1994), flax rust (Thrall et al. 2001), and rice blast (Dewit 1992), as well as several diseases of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Holub 2001).

In multilocus systems of host–parasite interactions, negative indirect frequency-dependent selection (FDS) is thought to account for the great polymorphism found in MHC genes (Apanius et al. 1997; Hill 2001; Borghans et al. 2004) and GFG genes (Frank 1993a; Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005). In this hypothesis, host and parasite genotypes have a selective advantage when they are rare in coevolving populations. This leads to sustained coevolutionary cycles because when a parasite rare allele is selected, its frequency increases, selecting in turn for the corresponding resistant host genotype. It is hypothesized that these regular cycles of genotype frequencies prevent invasion by a single genotype, especially when mutations introduce new alleles in populations (Sasaki 2000; Borghans et al. 2004). An important question about coevolution is therefore whether or not multilocus interactions are sufficient to maintain polymorphism by themselves or if other ecological and biological factors are required.

In GFG relationships in plants, resistance is induced if the plant has a resistance (RES) gene enabling recognition of a specific parasite avirulence (AVR) protein (Dangl and Jones 2001). The parasite is not detected by the host and resistance is not induced if the host has a susceptibility allele (res) or the parasite has a virulence allele (avr). The asymmetry of the GFG interaction implies that in the absence of other factors, there will be an “arms race,” as successive pairs of RES and AVR alleles are driven to fixation in host and parasite populations, respectively (Bergelson et al. 2001; Holub 2001). Accounting for the diversity observed at host and parasite GFG loci (Thrall et al. 2001; Laine 2004) is a significant challenge because a universally virulent pathogen genotype with an avr allele at each locus might be expected to become fixed as it can infect all plant genotypes (Frank 1993a; Segarra 2005).

Conditions for the maintenance of polymorphism in GFG interactions have been studied in a single-locus system, with a single matching pair of a host RES gene and a parasite AVR gene (Tellier and Brown 2007). Coevolution implies the existence of indirect FDS, because the rate of natural selection on RES depends on the frequency of avr and vice versa. Polymorphism can be maintained only if there is also negative, direct FDS, such that the strength of natural selection for the host resistance allele or the parasite virulence allele or both declines with increasing frequency of that allele itself (Tellier and Brown 2007). Thus, while costs of RES and avr are necessary to maintain polymorphism, they are not sufficient to do so in a single-locus system (Tellier and Brown 2007) or in multilocus GFG interactions (Sasaki 2000; Segarra 2005). In a single-locus GFG interaction, direct FDS is generated if the parasite passes through more than one generation in the same host individual, a feature that is common to most plant diseases. Such polycyclic diseases are characterized by an autoinfection rate, the percentage of parasite spores reinfecting the same host from one parasite generation to the next (Barrett 1980). In single-locus GFG interactions, stable long-term polymorphism can be most readily maintained in host and parasite populations at high autoinfection rates (Tellier and Brown 2007).

With respect to the stability of polymorphism, multilocus systems have behavior similar to that of single-locus GFG systems. For monocyclic diseases on annual plants (one parasite generation per host generation), long-term stable polymorphism with all possible host and parasite genotypes cannot be obtained (Sasaki 2000; Segarra 2005). However, multilocus interactions and high mutation rates increase the variance of the lifetime of a mutation (Sasaki 2000; Segarra 2005). Note that the dynamics of genotype frequencies in multilocus models are highly affected by stochastic processes (mutation and drift) when many loci are considered (Frank 1993a; Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005). Here, we investigate whether the existence of multiple GFG loci further stabilizes a system in which epidemiological and ecological factors generate direct FDS (Tellier and Brown 2007) or further increases the variance of the lifetime of transiently polymorphic alleles (Holub 2001; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005).

A key issue is to discover the epidemiological and genetic factors that cause polymorphism at host and parasite multiple loci to be transient or stable (arms race or trench warfare models) (Stahl et al. 1999; Holub 2001). We extend the results of Tellier and Brown (2007) to a multilocus GFG system with polycyclic disease, assuming realistically small costs of RES and avr. Mutation is included in this model because stochastic processes (mutation and drift) have been shown to play an important role in multilocus GFG coevolution (Frank 1993a; Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005). We show that polymorphism can be maintained at several host and parasite loci when the autoinfection rate is high. Moreover, compared to a single-locus GFG relationship, multilocus interactions diminish the minimum constitutive cost of each RES and avr allele necessary for polymorphism to be maintained.

A complication when moving from a single-locus to a multilocus model is the possible existence of interactions between loci. Functional studies of avr or RES alleles show increasing experimental evidence of epistatic effects between loci in parasites (Bai et al. 2000; Wichmann and Bergelson 2004; Kay et al. 2005; Mudgett 2005). In microbial parasites of plants, AVR proteins have a dual role: as well as being triggers for induction of host defenses upon recognition by RES proteins, some of them at least are pathogenicity effectors (Dangl and Jones 2001; Alfano and Collmer 2004; Skamnioti and Ridout 2005; Ridout et al. 2006). There may be partial complementation between AVR genes (Bai et al. 2000; Wichmann and Bergelson 2004; Kay et al. 2005; Mudgett 2005; Skamnioti and Ridout 2005), so increasing the number of mutations of AVR genes to avr alleles that have lost pathogenicity effector activity may have a synergistically negative effect on parasite fitness. In plants, on the other hand, RES genes induce the expression of similar defense processes (Brown 2003). Significant costs might therefore arise when one RES gene is expressed (Tian et al. 2003), but expression of numerous genes would not necessarily increase cost of defense very much (Bergelson and Purrington 1996). The models analyzed here incorporate functions to describe epistasis between the costs of multiple RES and avr alleles, depending on their number. For example, the marginal cost of adding a single new RES allele may decrease as the number of existing RES alleles increases, while the marginal cost of adding an avr allele may increase with the number of existing avr alleles. These epistatic cost functions are shown here to increase the parameter space in which stable polymorphism can be maintained in both host and parasite. This supports the hypothesis that multilocus GFG systems favor the maintenance of polymorphism at individual loci with the assumption of realistically small costs of RES and avr alleles.

TWO-LOCUS GFG MODEL WITH MONOCYCLIC DISEASE (MODEL A)

The model:

Model A describes a GFG system for two interacting loci in the host and the parasite. Both organisms reproduce clonally. Two alleles, RES and res in the host and AVR and avr in the parasite, are present at each locus and are coded 1 and 0, respectively (Frank 1993a; Sasaki 2000; Thrall and Burdon 2002). For example, a plant genotype with a RES allele at the first locus and a res allele at the second locus is described as 10, as is the parasite genotype with AVR at the first locus and avr at the second locus. An incompatible interaction occurs when the host RES allele matches the parasite AVR allele at least at one of the two interacting loci (1 matching at one or more loci; Frank 1993a). Following a common assumption of GFG relationships, an incompatible interaction results in the parasite being unable to infect the host successfully (Table 1; Dangl and Jones 2001). This model is based on Tellier and Brown (2007) and is a GFG system for monocyclic disease slightly simplified from Segarra (2005). Fitnesses of host and parasite genotypes are given in Table 1, with the following parameters: s is the cost to a plant of being diseased, u1 (u2) is the cost of one (or two) RES alleles, and b1 (b2) is the cost of one (or two) avr alleles. For instance, in Table 1, the fitness of a 10 parasite is 0 on plant genotypes 11 and 10 but (1 − b1) on plant genotypes 00 and 01. Recurrence equations for the frequencies of the genotypes are given in the appendix.

TABLE 1.

Host and parasite fitnesses for monocyclic disease and two loci in each species interacting by gene-for-gene relationships

| Parasite fitness

|

Host fitness

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | Aa | aA | aa | AA | Aa | aA | aa | |

| RR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 − b2 | 1 − u2 | 1 − u2 | 1 − u2 | (1 − s)(1 − u2) |

| Rr | 0 | 0 | 1 − b1 | 1 − b2 | 1 − u1 | 1 − u1 | (1 − s)(1 − u1) | (1 − s)(1 − u1) |

| rR | 0 | 1 − b1 | 0 | 1 − b2 | 1 − u1 | (1 − s)(1 − u1) | 1 − u1 | (1 − s)(1 − u1) |

| rr | 1 | 1 − b1 | 1 − b1 | 1 − b2 | 1 − s | 1-s | 1 − s | 1 − s |

Existence of equilibrium points:

Each genotype has an equilibrium frequency; for example, that of host genotype 11 is defined as  There are trivial equilibria defined by fixation of one or two host or parasite genotypes. Host equilibria are thus fixation of double-RES plants (

There are trivial equilibria defined by fixation of one or two host or parasite genotypes. Host equilibria are thus fixation of double-RES plants ( ), fixation of double-susceptibility (

), fixation of double-susceptibility ( ), and fixation of both single-resistant genotypes (

), and fixation of both single-resistant genotypes ( ). Similar conditions are found for parasite genotypes:

). Similar conditions are found for parasite genotypes:

and

and  The conditions for stability of these trivial equilibria are given in Sasaki (2000) and Segarra (2005).

The conditions for stability of these trivial equilibria are given in Sasaki (2000) and Segarra (2005).

The main point of interest here is the existence of multilocus polymorphism, defined as an equilibrium state with three or four host and parasite genotypes, as can be found in natural populations (Thrall et al. 2001; Laine 2004). This occurs at the nontrivial equilibrium, where host and parasite genotype frequencies are as follows:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

(analysis of recurrence equations is in the appendix with Mathematica 5.0; Wolfram Research 2003). Note that the equilibrium frequencies of host genotypes depend on costs of avr alleles (b2 and b1) while parasite equilibrium frequencies are functions of the costs of RES alleles (u2 and u1) and the cost of disease (s) (Frank 1992).

In Equation 1 the conditions for all host genotypes to exist simultaneously are: 0 <  < 1 (this is always true because 0 <

< 1 (this is always true because 0 <  ); 0 <

); 0 <  < 1 ⇒ b2 < 1 and b1 < 1/(2 − b2), which is reasonable, as costs of virulence tend to be small (Bergelson and Purrington 1996; Brown 2003); and

< 1 ⇒ b2 < 1 and b1 < 1/(2 − b2), which is reasonable, as costs of virulence tend to be small (Bergelson and Purrington 1996; Brown 2003); and

|

(3) |

Previous GFG models have assumed multiplicative costs of two single avr alleles where  (Segarra 2005). Condition (3) is fulfilled if the cost of having two avr alleles (b2) is greater than or equal to the multiplicative cost of two single avr alleles because

(Segarra 2005). Condition (3) is fulfilled if the cost of having two avr alleles (b2) is greater than or equal to the multiplicative cost of two single avr alleles because

In Equation 2 the conditions for all parasite genotypes to exist simultaneously are:  ⇒ u2 < s < 1 (otherwise virulent parasites are eliminated from the population); 0 <

⇒ u2 < s < 1 (otherwise virulent parasites are eliminated from the population); 0 <  < 1 ⇒ u2 > u1 [i.e., the cost of having two RES alleles must be larger than that of one RES allele (similarly

< 1 ⇒ u2 > u1 [i.e., the cost of having two RES alleles must be larger than that of one RES allele (similarly  )]; and

)]; and

|

(4) |

In previous GFG models, the costs of having two RES alleles have been multiplicative:  Condition (4) is not satisfied if the cost of having two RES alleles (u2) is equal to the multiplicative cost of two single RES alleles because

Condition (4) is not satisfied if the cost of having two RES alleles (u2) is equal to the multiplicative cost of two single RES alleles because

Equation 4 shows that when multiplicative costs are assumed (as in Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005), double-AVR parasites cannot be maintained in populations. Epistasis of fitness costs of RES and avr alleles is thus essential for the existence of an interior equilibrium point with all four host and all four parasite genotypes.

Stability of the equilibrium point:

Following analysis in Tellier and Brown (2007), we use a logit transformation of genotype frequencies in model A (appendix and supplemental Section 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), which simplifies considerably the analysis of the genotype dynamics. At host generation g:

|

(5) |

The change (Δ) in the ratio of parasite genotype 10 and 01 frequencies between generation g and g + 1 is then

|

(6) |

Thus the system of equations of model A (see appendix and supplemental Section 1) can be rewritten as

|

(7) |

where JA is the Jacobian matrix of the system. The dynamics of the system are determined by analysis of the eigenvalues of JA (see appendix). For a model with four variables, two pairs of eigenvalues (λ1,2 and λ3,4) are solutions of the characteristic polynomial equation of JA. The pairs of eigenvalues can be real  (and

(and  ) or complex

) or complex  (and

(and  ), with

), with

|

(8) |

(see appendix). An exact condition for stability of an interior equilibrium of this dynamical system with four variables (Equation 7) is that the four eigenvalues of JA must lie within a unit circle centered on (−1, 0) in the complex plane (Roughgarden 1996; Kot 2001). The following condition is derived from the Routh–Hurwitz criterion for stability of a dynamical system:

|

(9) |

(Roughgarden 1996; Kot 2001). For model A, the eigenvalues are

|

(10) |

with  and

and  Consequently, there is always at least one eigenvalue that does not verify condition (9), and the interior, nontrivial equilibrium (Equations 1 and 2) is always unstable. The mathematical reason for this is that all diagonal elements of JA are zero, and therefore α1 = α2 = 0 (Equation 8, appendix, and supplemental Section 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). The elements of JA are the rates of natural selection on the ratio of genotype frequencies. For example,

Consequently, there is always at least one eigenvalue that does not verify condition (9), and the interior, nontrivial equilibrium (Equations 1 and 2) is always unstable. The mathematical reason for this is that all diagonal elements of JA are zero, and therefore α1 = α2 = 0 (Equation 8, appendix, and supplemental Section 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). The elements of JA are the rates of natural selection on the ratio of genotype frequencies. For example,  is the rate of selection on the double-avr parasite genotype (00) as a function of its own frequency, i.e., the rate of direct FDS on 00 parasites (Tellier and Brown 2007). Therefore, α1 and α2 are the sums of the direct FDS coefficients for the four ratios of genotype frequency (Equation 8). Equation 10 demonstrates that for monocyclic diseases, there is no direct negative FDS for host or parasite genotypes, and a polymorphic state with three or four host and parasite genotypes is always unstable.

is the rate of selection on the double-avr parasite genotype (00) as a function of its own frequency, i.e., the rate of direct FDS on 00 parasites (Tellier and Brown 2007). Therefore, α1 and α2 are the sums of the direct FDS coefficients for the four ratios of genotype frequency (Equation 8). Equation 10 demonstrates that for monocyclic diseases, there is no direct negative FDS for host or parasite genotypes, and a polymorphic state with three or four host and parasite genotypes is always unstable.

TWO-LOCUS GFG MODEL WITH POLYCYCLIC DISEASE

Model description:

Model B is a multilocus GFG system with polycyclic disease, where polycyclic pathogens undergo several (G) multiplicative generations during one host generation. Here, the simplest case of G = 2 parasite generations per host generation is considered. The autoinfection rate (ψ) is the percentage of infectious spores that reinfect the same host plant in the second parasite generation (Barrett 1980; Tellier and Brown 2007). The cost to a plant of being diseased increases with the number of successive parasite infections, with a maximum fitness loss of φ after G parasite generations (Campbell and Madden 1990; Tellier and Brown 2007). The loss of plant reproductive output caused by disease increases disproportionately with π, the number of successful parasite generations on a host plant (π ≤ G) because, as the parasite grows multiplicatively, corresponding damage is done to the host (Campbell and Madden 1990). The plant fitness (F) is a decreasing function of π where z is a parameter defining the shape of the disease curve (z > 1):

|

(11) |

(Tellier and Brown 2007). ɛ is the decrease of plant fitness after π = 1 infection ( : Equation 11, G = 2, π = 1). For simplicity, the parasite reproductive fitness does not depend on π. Deterministic equations for evolution of genotype frequencies in time are given below and can be obtained from fitnesses given in supplemental Tables S1 and S2 (supplemental Section 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/,). Table 2 is a summary of equations in model B with only autoinfection (ψ = 1).

: Equation 11, G = 2, π = 1). For simplicity, the parasite reproductive fitness does not depend on π. Deterministic equations for evolution of genotype frequencies in time are given below and can be obtained from fitnesses given in supplemental Tables S1 and S2 (supplemental Section 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/,). Table 2 is a summary of equations in model B with only autoinfection (ψ = 1).

TABLE 2.

Fitness of hosts and parasites in model B for interactions with two parasite generations per host generation (G = 2) and only autoinfection between parasite generations (ψ = 1)

| Parasite genotypes (frequencies) within host generation g

|

Fitness at beginning of host generation g + 1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| First generation | Second generation | Fitness of second parasite infection | Host fitness |

| Host genotype 11 (RRg) | |||

| 11 (AAg) | 11 (AA1) | 0 | 1 − u2 |

| 10 (Aag) | 10 (Aa1) | 0 | 1 − u2 |

| 01 (aAg) | 01 (aA1) | 0 | 1 − u2 |

| 00 (aa1) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u2)(1 − ɛ) | |

| 00 (aag) | 00 (aag) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u2)(1 −φ) |

| Host genotype 00 (rrg) | |||

| 00 (aag) | 00 (aag) | 1 − b2 | (1 −φ) |

| 01 (aAg) | 10 (aAg) | 1 − b1 | (1 −φ) |

| 10 (Aag) | 10 (Aag) | 1 − b1 | (1 −φ) |

| 11 (AAg) | 11 (AAg) | 1 | (1 −φ) |

| Host genotype 01 (rRg) | |||

| 11 (AAg) | 11 (AA1) | 0 | 1 − u1 |

| 01 (aAg) | 01 (aA1) | 0 | 1 − u1 |

| 00 (aa1) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u1)(1 − ɛ) | |

| 10 (Aa1) | 1 − b1 | (1 − u1)(1 − ɛ) | |

| 00 (aag) | 00 (aag) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u1)(1 −φ) |

| 10 (Aag) | 10 (Aag) | 1 − b1 | (1 − u1)(1 −φ) |

| Host genotype 10 (Rrg) | |||

| 11 (AAg) | 11 (AA1) | 0 | 1 − u1 |

| 10 (Aag) | 10 (Aa1) | 0 | 1 − u1 |

| 00 (aa1) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u1)(1 − ɛ) | |

| 01 (aA1) | 1 − b1 | (1 − u1)(1 − ɛ) | |

| 00 (aag) | 00 (aag) | 1 − b2 | (1 − u1)(1 −φ) |

| 01 (aAg) | 10 (aAg) | 1 − b1 | (1 − u1)(1 −φ) |

As an example, the outcome of infection on plant genotype 11 is described below (supplemental Table S1 in supplemental Section 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). In the first parasite generation (π = 1), a 11 plant can encounter parasite genotypes 11, 01, or 11 that cannot infect it successfully. In the second parasite generation (π = 2), that plant can then either (i) encounter spores from the same genotypes (frequencies AA1, Aa1, aA1) that cannot infect it (the plant's fitness is then 1 − u2) or (ii) be infected by the supervirulent genotype 00 (frequency aa1), so its fitness is (1 − u2)(1 − ɛ).

On the other hand, when 11 plants are infected by a supervirulent (00) parasite at π = 1 (frequency aag at the start of generation g) the following occurs at π = 2:

A proportion ψ of these plants remain infected by the same parasite genotype (autoinfection). A proportion ψaagRRg of all the plants in the population has fitness (1 − u2)(1 − φ) after two consecutive successful infections.

A proportion 1 − ψ are allo-infected by virulent parasites (here, only those with the supervirulent genotype 00) produced in the first parasite generation with frequency aa1 [proportion (1 − ψ)aagaa1RRg]. These plants are also infected twice and have fitness (1 − u2)(1 − φ).

A proportion 1 − ψ may encounter spores from the first parasite generation of the genotypes 01, 01, or 11 (frequencies AA1, Aa1, and aA1) that cannot infect. Their fitness is (1 − u2)(1 − ɛ).

Formulas:

The following are deterministic equations for a two-locus GFG system with two parasite generations per host generation with independent fitness costs of host resistance or parasite virulence alleles at different loci and no mutation. Frequencies of parasite genotypes after the first parasite generation are identical to those in model A (see Table 2 and supplemental Section 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/):

|

|

After the second parasite generation (i.e., at the start of the next host generation, g + 1), parasite genotype frequencies are as follows:

Ratio of parasite genotype frequencies 00 to 11:

|

Ratio of parasite genotype frequencies 10 to 01:

|

The ratios of host genotype frequencies at the end of host generation g and the start of generation g + 1 are as follows:

Ratio of host genotype frequencies 01 to 10:

|

Ratio of host genotype frequencies 00 to 11:

|

Existence of equilibrium point (ψ = 1):

The same trivial equilibrium points exist as in model A. The complexity of the equations in model B constrains analysis of the nontrivial equilibrium point to the case when there is only autoinfection (ψ= 1). Owing to quadratic terms and the nonlinear behavior of model B, the following assumptions were made: (i)  and (ii) b1 is small so that (1 − b1) ≈ 1 and (1 − b1)(1 − b2) ≈ (1 − b2). The accuracy of these approximations and of the following equilibrium frequencies was tested numerically across a wide range of parameter values. Theoretical values obtained with Mathematica 5.0 (Wolfram Research 2003) were compared to numerically simulated values, calculated as the mean of genotype frequencies over the last 100 generations of 5000 simulated host generations. These approximations (Equations 12 and 14) are accurate for moderate to high values of φ, but less accurate for values of

and (ii) b1 is small so that (1 − b1) ≈ 1 and (1 − b1)(1 − b2) ≈ (1 − b2). The accuracy of these approximations and of the following equilibrium frequencies was tested numerically across a wide range of parameter values. Theoretical values obtained with Mathematica 5.0 (Wolfram Research 2003) were compared to numerically simulated values, calculated as the mean of genotype frequencies over the last 100 generations of 5000 simulated host generations. These approximations (Equations 12 and 14) are accurate for moderate to high values of φ, but less accurate for values of  when φ < u1 or values of

when φ < u1 or values of  when u1 < φ < u2 (supplemental Section 3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), as

when u1 < φ < u2 (supplemental Section 3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), as

|

(12) |

|

|

where  In Equation 12 the conditions for all parasite genotypes to exist simultaneously are

In Equation 12 the conditions for all parasite genotypes to exist simultaneously are  and

and  (similarly for

(similarly for  ):

):

|

(13) |

In contrast to model A (Equation 4), condition (13) is fulfilled if the cost of having two RES alleles (u2) is lower than or equal to the multiplicative cost of two single RES alleles. The equilibrium frequency of double-AVR parasites increases when the difference between u2 and u1 diminishes:

|

(14) |

|

|

In Equation 14 the conditions for all host genotypes to exist simultaneously are

and

and  because

because  and

and  by definition:

by definition:

|

(15) |

Condition (15) is identical to Equation 3 and is fulfilled if the cost of having two avr alleles (b2) is greater than or equal to the multiplicative cost of two single avr alleles. The equilibrium frequency of double-RES plants becomes higher with a greater difference between b2 and b1.

Stability of the equilibrium point:

The local stability of the nontrivial equilibrium is analyzed when there is only auto-infection (ψ= 1) because in this situation, stable polymorphism occurs over a wider parameter space (Tellier and Brown 2007). The main differences from model A are that the following coefficients are not zero (supplemental Section 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/):

|

(16) |

This coefficient is always negative as

|

(17) |

This coefficient is also negative as

The Jacobian matrix for model B, JB, can thus be rewritten:

|

(18) |

Approximations for the elements x1, x2, x3, x4 are derived in supplemental Section 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/. JB is diagonalizable and has two pairs of eigenvalues (λ1,2 and λ3,4) that can be real,

|

(19) |

and

|

or complex,

|

(20) |

and

|

A necessary condition for stability (Equation 9) is verified because  and

and  are both negative. However, a second condition for stability is that both absolute values of the discriminants of the characteristic polynomial,

are both negative. However, a second condition for stability is that both absolute values of the discriminants of the characteristic polynomial,  and

and  must be <1 (Equation 9). Analytical derivation of this second condition is not possible because of the nonlinearity of equations in model B and because only approximations of the equilibrium genotype frequencies can be obtained.

must be <1 (Equation 9). Analytical derivation of this second condition is not possible because of the nonlinearity of equations in model B and because only approximations of the equilibrium genotype frequencies can be obtained.

Simulation methods:

Host and parasite genotype frequencies were therefore simulated numerically for different values of ψ and φ. Simulations were run in Matlab version 7.0 (Release 14) for 15,000 host generations, by which time stable behavior (or genotype fixation) was achieved, with different sets of initial host and genotype frequencies (all host and parasite genotypes were present at the beginning of each simulation). The system was considered to be stable when the amplitude of the fluctuations of each genotype frequency decreased in time and converged toward an equilibrium value for any of the initial allele frequencies tested.

Mutations, especially with high mutation rates, regularly introduce new rare genotypes into host and parasite populations (Kirby and Burdon 1997; Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005). We therefore compared results of simulations with and without mutation. One set of simulations was done with a mutation rate of 10−5. A second set of simulations assumed two different mutation rates: 10−5 if a mutation results in a loss of function (from RES to res and from AVR to avr) and 10−8 for a gain-of-function mutation in the reverse direction (from res to RES or from avr to AVR) (Kirby and Burdon 1997). A host or parasite genotype was considered lost from a population when its frequency was <10−6, but could be subsequently reintroduced by mutation (if any). On the other hand, a genotype was fixed in a population when its frequency was >1 − 10−6. For a given set of parameter values, the results of the different types of simulations (with and without mutations or with different initial genotype frequencies) were compared. The description of results follows with models B1 and B2.

MULTIPLICATIVE CONSTITUTIVE COSTS (MODEL B1)

Model B1 is a two-locus GFG system with multiplicative costs of RES and avr alleles, i.e., no epistatic interactions among loci for fitness values (Frank 1993b; Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005). Recurrence equations for genotype frequencies are those of model B, where b2 and u2 are the costs of having two RES or avr alleles:

|

(21) |

Simulations were run with b1 = u1 = 5% and b2 = u2 = 9.75%, these values being chosen to allow comparison with single-locus results (Tellier and Brown 2007). When there is only auto-infection (ψ = 1), the double-RES genotype has a very low equilibrium frequency (<10−4, Equation 14). Model B1 is tested numerically to determine if the equilibrium point with all host and parasite genotypes exists for different values of ψ and to discover the range of parameter values of ψ and φ for which the equilibrium point is stable.

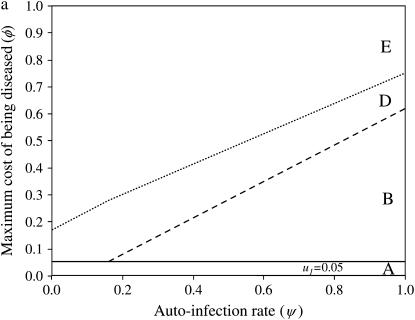

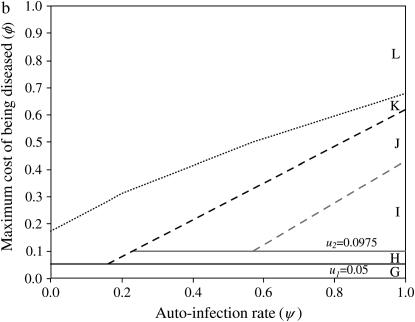

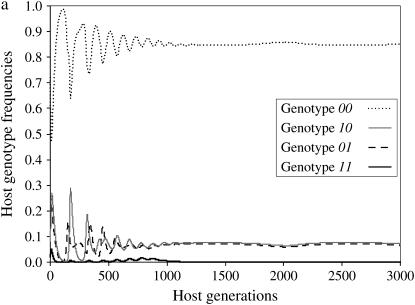

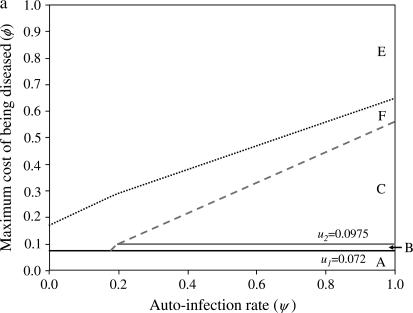

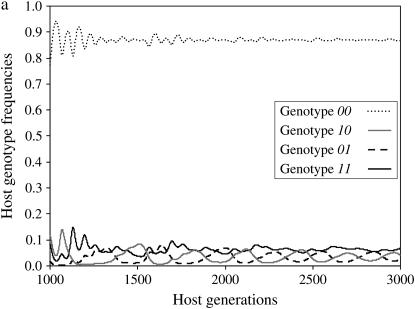

Results of simulations are summarized in Figure 1 by the state of the system (stable or unstable) and the genotypes maintained in the host (Figure 1a) and parasite (Figure 1b) populations. Figure 2a shows the dynamics of host genotype frequencies in one simulation typical of area B of Figure 1a with stable polymorphism of three host genotypes (00, 10, 01). Similarly, Figure 2b shows the dynamics of parasite gene frequencies in area I of Figure 1b where there is stable polymorphism of all four parasite genotypes, with genotype 11 at a very low frequency. Typical simulation results for each area of Figure 1 are provided in supplemental Section 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Figure 1.—

Stability area plots for a two-locus model with independent costs of alleles at different loci (model B1), in relation to values of the autoinfection rate (ψ) and the cost to a plant of being diseased by two parasite generations (φ). u1, u2, costs of host resistance; b1, b2, costs of parasite virulence; u1 = b1 = 0.05, u2 = b2 = 0.0975 (subscript 1, cost of one allele; subscript 2, cost of two alleles). (a) Stability of polymorphism in the host population. Area A, fixation of double-susceptible genotype 00; area B, stable polymorphism with 00 and the single-resistant genotypes 10 and 01; area D, unstable polymorphism with 00, 10, 01; area E, fixation of 00. (b) Stability of polymorphism in the parasite population. Area G, fixation of the double-avirulent genotype 11; area H, stable polymorphism with 11 and the single-avirulent genotypes 01 and 10; area I, stable polymorphism with all four genotypes; area J, stable polymorphism with 10, 01, and the double-virulent genotype 00; area K, unstable polymorphism with 10, 01, 00; area L, fixation of 00.

Figure 2.—

Dynamics of host and parasite genotype frequencies in a two-locus model with independent costs of alleles at different loci (model B1) defined by two loci as a function of the number of host generations. There is no mutation. Autoinfection rate ψ = 0.9 and maximum cost of disease φ= 0.2. u1, u2, costs of host resistance; b1, b2, costs of parasite virulence; u1 = b1 = 0.05, u2 = b2 = 0.097. (a) Maintenance of host genotypes with one or both susceptibility alleles but the double-resistant genotype 11 is eliminated (area B in Figure 1a). (b) Maintenance of all four parasite genotypes (area I in Figure 1b).

If disease severity is smaller than the cost of one RES allele, there is fixation of host res alleles (00) because there is no net advantage to resistance (area A in Figure 1a). As a result, AVR alleles (11) are fixed in the parasite population because virulence is costly (area G in Figure 1b). In mathematical terms, areas A and G correspond to the situation with zero (or negative) equilibrium frequencies of parasite genotypes 01, 10, and 11 because φ< u1 < u2 (Equations 12). The limit of areas A and G is thus the cost of one RES allele (φ= u1).

At medium to high autoinfection (ψ) and low to medium disease severity (φ), there is stable polymorphism of three host genotypes (00, 10, 01) (Figure 1a, area B, and Figure 2a). Double-resistant plants (11) are eliminated from the population because the benefit of being superresistant (not being infected) is not large enough to overcome the cost of having two RES alleles. As a consequence, when u1 < φ< u2 and autoinfection rates are intermediate to high, because avr alleles are costly, double-avr parasites are eliminated from the parasite population (area H in Figure 1b). Stable polymorphism with parasite genotypes 11, 10, and 01 occurs. Mathematically, area H corresponds to a situation where the double-avr equilibrium frequency is zero (or negative) as φ< u2 (Equation 12).

With increasing φ and high autoinfection rates, all four parasite genotypes (00, 01, 10, 11) coexist in stable polymorphism (area I, Figure 1b) because there is direct FDS acting on parasite genes (Equations 16 and 17), and the interior equilibrium for all possible parasite genotypes exists (Equation 12; Figure 2b). The parameter space in which polymorphism is stable diminishes with increasing φ, because resistant genotypes (10 and 01) are selected more strongly, in turn selecting for double-avr parasites (00). Therefore, at intermediate to high ψ, increasing φ favors double-avr parasites and counterselects double-AVR genotypes (11) (area J). In area J, values of ψ and φ do not allow the existence of an interior equilibrium frequency for the double-AVR parasite (Equation 12).

A key result is that the size of areas H, I, and J in Figure 1b matches that of area B in Figure 1a. This is because stability of polymorphic state depends on the strength of direct FDS against strength of indirect FDS, both of which are determined by ψ and φ. Therefore, conditions for stability are identical for host and parasite populations, as shown for single-locus interactions (Tellier and Brown 2007), and only the existence of equilibrium frequencies of the various genotypes discriminates between the different dynamics in host and parasite populations. Moreover, the equilibrium frequency of the double-avr genotype (00) increases with φ (Equation 12) and always has the highest frequency in the parasite population. This is in agreement with observations from surveys in natural populations (Dinoor and Eshed 1987; Bevan et al. 1993; Thrall et al. 2001) (Figure 3b).

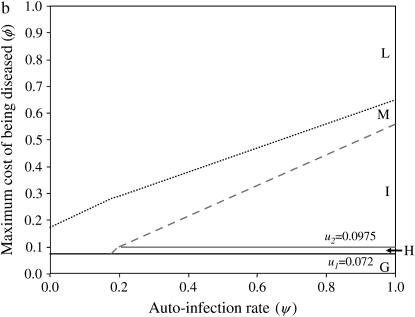

Figure 3.—

Stability area plots for a two-locus model with epistasis in costs of alleles at different loci (model B2), in relation to values of the autoinfection rate (ψ) and the cost to a plant of being diseased by two parasite generations (φ). u1, u2, costs of host resistance; b1, b2, costs of parasite virulence; u1 = 0.072 and b1 = 0.024; u2 = b2 = 0.0975. (a) Stability of polymorphism in the host population. Area A, fixation of double-susceptible genotype 00; area B, stable polymorphism with 00 and the single-resistant genotypes 10 and 01; area C, stable polymorphism with all four genotypes (10, 01, 00, 11); area F, unstable polymorphism with all four genotypes; area E, fixation of 00. (b) Stability of polymorphism in the parasite population. Area G, fixation of the double-avirulent genotype 11; area H, stable polymorphism with 11 and the single-avirulent genotypes 01 and 10; area I, stable polymorphism with all four genotypes (10, 01, 00, 11); area M, unstable polymorphism with all four genotypes; area L, fixation of the double-virulent genotype 00.

When there is a high cost of disease (high φ) (Figure 1, a and b), there is first strong selection for resistant host genotypes 01, 10, 11. They select strongly for virulent parasite genotypes and especially for the double-avr genotype (00). Very high frequencies of double-avr parasite (area K, Figure 1b) then lead to a long-term increase of the double-susceptible genotype frequency (00) because RES alleles are costly. At very high φ, this results in the fixation of the double-avr parasite genotype and the double-susceptible host genotype (areas E and L in Figure 1). The dynamical system is unstable when φ increases, because the indirect FDS overrides the direct frequency-dependent stabilizing effect (areas D and K).

Realistic mutation rates do not affect the behavior of the model (stability or instability) or frequencies at equilibrium in stable areas (B in Figure 1a and H–J in Figure 1b). Without mutation, when the system is unstable (areas D and E in Figure 1a and K and L in Figure 1b) there is fixation of the double-avr parasite genotype. Mutations can sustain stochastic coevolutionary cycles by recurrent introduction of new rare genotypes in areas D and K, following an arms race model. However, as the system has unstable behavior (areas D and E in Figure 1a and K and L in Figure 1b) each coevolutionary cycle results in the fixation of the double-avr parasite until a new mutation arises.

EPISTATIC INTERACTIONS AMONG LOCI (MODEL B2)

In model B2 epistatic interactions are assumed between loci both in host and in parasite. General expressions are shown here for the costs of multiple avr (or RES) alleles in a multilocus GFG system with n loci. The maximum cost of having n avr (or RES) alleles is bmax (umax).

The cost bk of having k avr alleles is thus

|

(22) |

The marginal cost of each additional mutation from AVR to avr increases exponentially with the number of existing avr alleles, such that the loss of two AVR functions is more costly to the pathogen than expected if the costs were independent; therefore, we choose θ > 1, and the cost curve has a convex shape. In model B2, n = 2 so bmax = b2.

On the other hand, the marginal cost of each additional RES allele diminishes with increasing number of existing RES alleles, so the cost of two RES alleles is lower than expected if the costs at different loci were independent. The cost curve has a concave shape when ξ < 1. The cost uk of having k RES alleles is thus

|

(23) |

In model B2, n = 2 so umax = u2. To compare results from models B1 and B2, the cost of having two alleles is fixed to 0.0975 (u2 = b2 = 0.0975, Equation 6). The only difference between models B1 and B2 is then the cost of having one allele with u1 = 0.072 (ξ = 0.4) and b1 = 0.024 (θ = 2). Results for each area of Figure 3 can be seen in supplemental Section 6 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/.

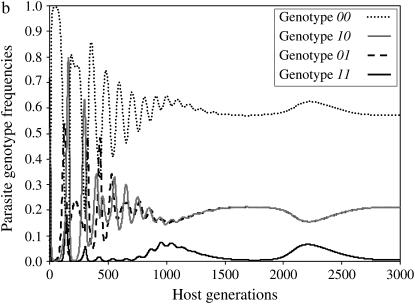

In model B2, stable polymorphism with all four genotypes is maintained in host (area C in Figures 3a and 4a) and parasite populations (area I in Figures 3b and 4b) with medium to high ψ. This occurs because the equilibrium frequency of double-RES hosts increases in proportion to the difference between b1 and b2 (Equation 14). In other words, increasing the cost of having two avr alleles compared to the cost of one avr allele favors parasite genotypes 01 and 10, thus enhancing selection for double-RES host genotypes and increasing the value of  (Figure 4a). In simulations conducted with epistasis between parasite loci and multiplicative costs of RES alleles, there is also stable polymorphism with all four host and parasite genotypes (data not shown). Moreover, epistasis among host loci that decreases the difference between u1 and u2 has the effect of diminishing the equilibrium frequency of double-avr parasites and increasing that of double-AVR parasites. The diminution of the cost of having two RES alleles compared to that of one RES allele decreases selection for host genotypes 01 and 10, thus enhancing selection for double-AVR genotypes and increasing the value of

(Figure 4a). In simulations conducted with epistasis between parasite loci and multiplicative costs of RES alleles, there is also stable polymorphism with all four host and parasite genotypes (data not shown). Moreover, epistasis among host loci that decreases the difference between u1 and u2 has the effect of diminishing the equilibrium frequency of double-avr parasites and increasing that of double-AVR parasites. The diminution of the cost of having two RES alleles compared to that of one RES allele decreases selection for host genotypes 01 and 10, thus enhancing selection for double-AVR genotypes and increasing the value of  (Figure 4b).

(Figure 4b).

Figure 4.—

Dynamics of host and parasite genotype frequencies in a two-locus model with epistasis in costs of alleles at different loci (model B2) as a function of the number of host generations. There is no mutation. Autoinfection rate ψ = 0.9 and maximum cost of disease φ= 0.2. u1, u2, costs of host resistance; b1, b2, costs of parasite virulence; u1 = 0.072 and b1 = 0.024; u2 = b2 = 0.0975. (a) Maintenance of all four host genotypes (area C in Figure 3a). (b) Maintenance of all four parasite genotypes (area I in Figure 3b).

The total stability area for the host in model B2 (C and B in Figure 3a) has a comparable size but is not identical to area B in Figure 1a (model B1). For the parasite, stability areas H and I together in Figure 3b have a comparable size but are not identical to areas H, I, and J together in Figure 1b (model B1). The areas for stable polymorphism are comparable because conditions for stability depend on the strength of direct FDS, which mainly depends on ψ and φ (see Equations 19 and 20). However, stability conditions also depend on costs of RES and avr alleles (Equations 16 and 17), which differ between models B1 and B2, which is why stability areas do not overlap exactly between Figures 1 and 2. Although all four host and parasite genotypes can be maintained, double-res plants and double-avr parasites have higher equilibrium frequencies than the other genotypes, in agreement with results from natural populations (Thrall et al. 2001) (Figure 4, a and b).

In model B2, the equilibrium point with the four host and parasite genotypes exists. However, when φ increases, because indirect FDS overrides the stabilizing effect of direct FDS, this equilibrium state becomes unstable in areas F (Figure 3a) and M (Figure 3b).

Other results from model B2 are similar to those from model B1. If φ< u1, host genotype 00 (area A in Figure 3a) and parasite genotype 11 (area G in Figure 3b) become fixed. When u1 < φ< u2, and ψ is intermediate to high, double-RES genotypes and double-avr parasites are eliminated, respectively, from the host (area B in Figure 3a) and parasite (area H in Figure 3b) populations. In areas B and H, there is stable polymorphism with three host and three parasite genotypes. Finally, at very high φ, there is fixation of the 00 host and parasite genotypes (areas E and L in Figure 3). Simulations for more than two loci generalize our conclusions from models B, showing the generality of the approach (n = 3 in supplemental Section 7 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

DISCUSSION

As in the single-locus model of Tellier and Brown (2007), polycyclic disease gives rise to conditions that stabilize polymorphism at equilibrium (model B, cf. model A). Stable polymorphism with three or four host genotypes and four parasite genotypes occurs at intermediate to high rates of autoinfection (model B). For monocyclic disease (model A), there is no direct FDS in the host ( ) or parasite (

) or parasite ( ) populations (Equation 10). Polymorphism is stabilized in polycyclic diseases, because the stability of GFG systems depends on the outcome of infection in the first parasite generation (g, 1) influencing the second parasite generation (g, 2). Model B extends the principle of single-locus GFG coevolution (Tellier and Brown 2007) to multiple loci. Polycyclic disease generates direct FDS for parasite virulence (

) populations (Equation 10). Polymorphism is stabilized in polycyclic diseases, because the stability of GFG systems depends on the outcome of infection in the first parasite generation (g, 1) influencing the second parasite generation (g, 2). Model B extends the principle of single-locus GFG coevolution (Tellier and Brown 2007) to multiple loci. Polycyclic disease generates direct FDS for parasite virulence ( and

and  ) but not for host resistance (

) but not for host resistance ( ). Increasing alloinfection (decreasing ψ) tends to make successive parasite generations on the same plant independent of one another, causing selection against parasite genotypes to tend to become independent of their own frequency (Tellier and Brown 2007) and decreasing the parameter space in which polymorphism is stable. This can be explained as follows.

). Increasing alloinfection (decreasing ψ) tends to make successive parasite generations on the same plant independent of one another, causing selection against parasite genotypes to tend to become independent of their own frequency (Tellier and Brown 2007) and decreasing the parameter space in which polymorphism is stable. This can be explained as follows.

The coefficient  tends to zero when ψ is small. When the frequency (AA) of the double-AVR parasite (genotype 11) is high and ψ is low, most double-RES plants infected by double-avr parasites in (g, 1) then encounter a double-AVR parasite in (g, 2). Increasing ψ, however, increases the probability of these double-RES plants remaining infected with a double-avr parasite in (g, 2). Hence at higher frequencies of double-AVR parasites and increasing autoinfection, the strength of natural selection for the double-avr genotype and against double-AVR becomes greater (

tends to zero when ψ is small. When the frequency (AA) of the double-AVR parasite (genotype 11) is high and ψ is low, most double-RES plants infected by double-avr parasites in (g, 1) then encounter a double-AVR parasite in (g, 2). Increasing ψ, however, increases the probability of these double-RES plants remaining infected with a double-avr parasite in (g, 2). Hence at higher frequencies of double-AVR parasites and increasing autoinfection, the strength of natural selection for the double-avr genotype and against double-AVR becomes greater ( is more negative). Similarly, the coefficient

is more negative). Similarly, the coefficient  tends to zero when ψ is low. When the frequency (Aa) of parasite genotype 10 and ψ are both low, most 01 plants infected by 10 parasites in (g, 1) then encounter a 01 parasite in (g, 2). Increasing ψ, however, increases the probability of these 01 plants remaining infected with a 10 parasite in (g, 2). Hence, natural selection for parasite genotype 10 and against 01 is stronger (

tends to zero when ψ is low. When the frequency (Aa) of parasite genotype 10 and ψ are both low, most 01 plants infected by 10 parasites in (g, 1) then encounter a 01 parasite in (g, 2). Increasing ψ, however, increases the probability of these 01 plants remaining infected with a 10 parasite in (g, 2). Hence, natural selection for parasite genotype 10 and against 01 is stronger ( is more negative) when the frequency of 10 parasites is lower, and this effect is stronger as ψ increases.

is more negative) when the frequency of 10 parasites is lower, and this effect is stronger as ψ increases.

The absence (model B1, Figures 1 and 2) or presence (model B2, Figures 3 and 4) of epistatic interactions between fitness costs at different GFG loci has a considerable influence on the maintenance of multiple genotypes in host and parasite populations. Epistatic interactions between virulent loci allow the existence of stable equilibrium frequencies of plant genotypes with multiple RES alleles. In two-locus systems, double-resistant plants (11) are maintained if avr alleles have a negative synergistic effect on parasite fitness (model B2), and these results extend to three-locus interactions (model C in supplemental Section 7 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). In biological terms, increasing exponentially the cost of each avr allele as a function of the total number of avr alleles counterselects genotypes with multiple avr alleles. The resulting higher parasite genotypic diversity then favors multiple-RES plant genotypes. Moreover, when the cost of each RES allele diminishes as a function of the total number of RES alleles, this counterselects host genotypes with intermediate numbers of RES alleles and favors double-res plants. Parasites with few AVR alleles are then favored against super-avr parasites that have high costs of avr. As a consequence, the equilibrium point with all four parasite genotypes is more likely to exist.

Epistatic interactions between RES and avr loci are interesting in relation to current advances in research on the function of RES and avr genes. To date, the great majority of experiments on plant and parasite fitness have been conducted on single genes (RES or avr). Some (Leonard 1969; Vera Cruz et al. 2000; Thrall and Burdon 2003; Tian et al. 2003) but not all (Bergelson and Purrington 1996; Vera Cruz et al. 2000; Brown 2003) experiments have detected such costs. The structure of fitness costs emerging from current research in molecular biology supports the hypothesis that epistasis is of the type that leads to GFG polymorphism being stable (and hence detectable).

Avirulence genes in plant parasites have a dual role. The proteins they encode are recognized by the host plant's defense machinery, and hence their avirulence function, similar to the antigenicity of parasites of vertebrates. However, many AVR proteins also have effector activity, promoting infection, colonization, or pathogenicity (Skamnioti and Ridout 2005; Jones and Dangl 2006; Ridout et al. 2006). Parasites generally have numerous avirulence/effector genes (Kay et al. 2005) and there is evidence for redundancy between AVR proteins (Bai et al. 2000; Wichmann and Bergelson 2004; Kay et al. 2005; Mudgett 2005; Skamnioti and Ridout 2005). Increasing the number of mutations of AVR genes to avr alleles may therefore have a synergistic negative effect on parasite fitness (infectivity, growth, reproduction, etc.). In experiments on multiple knockouts of avirulence/effector genes in Xanthomonas axonopodis, the loss of function of one or two of four avirulence genes did not affect significantly bacterial growth, but a significant effect was observed when three or four genes were knocked out (Wichmann and Bergelson 2004). Several parasite AVR genes exist as gene families and are thus predicted to complement each other's effector function to some extent (e.g., Blumeria graminis; Skamnioti and Ridout 2005; Ridout et al. 2006). Whether such a situation is general is not yet known, but if the cost of having one or very few avr alleles is low (2% in model B2), it might explain the lack of experimental evidence for a high cost of a single virulence allele (Vera Cruz et al. 2000; Thrall and Burdon 2003). It is also predicted that polymorphism would be commonly observed in multigene families where there is synergistic epistasis of the costs of different avr alleles, as in models B2 and C. An experiment to test this prediction would estimate the fitness costs of combinations of various numbers of AVR genes in a common background (Wichmann and Bergelson 2004).

Antagonistic interactions between RES alleles in their effect on host fitness are not essential to maintain polymorphism in parasite genotypes, but favor maintenance of genotypes with a low to intermediate number of avr alleles. We assume here that the cost of having one RES allele is high (7% in our simulations compared to 9% found by Tian et al. 2003), but that the marginal cost of each new RES allele added at other loci diminishes (here only 2% more cost for the second allele). High costs of RES have been found experimentally (Tian et al. 2003), but if different RES genes each had such a cost, the fitness of a plant with several RES genes would be severely depressed (Brown 2003). However, if the marginal cost of adding a new RES gene is small, the fitness load of many RES genes may not be much greater than that of one (Bergelson and Purrington 1996; Palomino et al. 2002). Functional data on resistance reactions show that many RES genes activate similar defense proteins (Jones and Dangl 2006). The cost of expressing host defenses may be similar whether they are triggered by a single RES–AVR interaction or by several pairs of RES and AVR genes.

Other theoretical models have suggested that multilocus GFG systems for monocyclic disease enhance polymorphism maintenance (Frank 1993a, 1997; Sasaki 2000; Thrall and Burdon 2002; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005). In a multilocus GFG coevolutionary system with n interacting loci, there are 2n genotypes in host and parasite. An increase in n also diminishes the expected frequency of each host and parasite genotype to a mean equilibrium frequency of 1/2n (Frank 1993a, 1997). In finite and spatially structured populations, allele frequencies in a high-dimension system (high n) are thus more sensitive to random processes (mutations, genetic drift, and migrations) counteracting the frequency-dependent selection process (Frank 1993a, 1997; Thrall and Burdon 2002). High mutation rates (Sasaki 2000; Salathe et al. 2005; Segarra 2005) introduce new genotypes at high frequencies and sustain successive stochastic frequency-dependent selection cycles. As there is no direct frequency-dependent selection in simple models of monocyclic disease, mutation lead to arms race coevolutionary dynamics, with recurrent fixation of alleles, rather than trench warfare dynamics, with stable polymorphism. Interestingly, in our models, realistic rates of mutation do not affect the outcome of coevolution in terms of the stability of polymorphism or the number of genotypes maintained but merely increase the time to genotype fixation and the lifetime of a mutation (this was also shown by Segarra 2005).

Polycyclic disease and autoinfection are important features of many diseases of plants and animals and have been shown to favor stable long-term maintenance of polymorphism at host and parasite loci (Tellier and Brown 2007). Here, a similar outcome is observed in multilocus GFG interactions with realistic costs of RES and avr alleles (model B1), in contrast to monocyclic disease (model A). Models B2 and C indicate the importance of epistatic interactions between host and parasite loci for costs of multiple RES and avr alleles and predict that GFG polymorphism will be stable (and hence detectable) when there is precisely the structure of costs that seems to be emerging from current discoveries in molecular biology.

APPENDIX: TWO-LOCUS GFG MODEL WITH MONOCYCLIC DISEASE

The model:

The parasite genotype frequencies at host generation g are AAg, Aag, aAg, and aag for the genotypes 11, 10, 01, and 00, respectively. Similarly, rrg, rRg, Rrg, and RRg stand for the frequencies in generation g of the respective host genotypes 11, 10, 01, and 00. The frequency of parasite genotype 11 in host generation g + 1 is thus  Similarly,

Similarly,

|

|

and

|

Where  is the overall parasite population fitness,

is the overall parasite population fitness,

|

Host 11 genotype frequency at host generation g + 1 is then

|

and

|

|

|

Where  is the overall host population fitness,

is the overall host population fitness,

|

Stability of the equilibrium state:

Using logit transformations of the above equations (Equations 5 and 6 in the text), the Jacobian matrix JA can be rewritten:

|

The coefficients of JA are the rates of natural selection of the ratio of genotype frequencies. For example,  is the rate of selection on the double-avr parasite genotype (00) as a function of the frequency of the double-susceptible host genotype (00). Close to the equilibrium point, the Jacobian matrix coefficients are approximately

is the rate of selection on the double-avr parasite genotype (00) as a function of the frequency of the double-susceptible host genotype (00). Close to the equilibrium point, the Jacobian matrix coefficients are approximately

|

(supplemental Section 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). The Jacobian matrix JA is diagonalizable and thus has four eigenvalues (λ1–4):

|

with

|

and

|

The sign of β1 depends on values of costs (u1, u2, b1, b2, s), and β2 is always positive.

References

- Alfano, J. R., and A. Collmer, 2004. Type III secretion system effector proteins: double agents in bacterial disease and plant defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42: 385–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apanius, V., D. Penn, P. R. Slev, L. R. Ruff and W. K. Potts, 1997. The nature of selection on the major histocompatibility complex. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 17: 179–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J. F., S. H. Choi, G. Ponciano, H. Leung and J. E. Leach, 2000. Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae avirulence genes contribute differently and specifically to pathogen aggressiveness. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13: 1322–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, J. A., 1980. Pathogen evolution in multilines and variety mixtures. Z. Pflanzenk. Pflanzens.-. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 87: 383–396. [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson, J., and C. B. Purrington, 1996. Surveying patterns in the cost of resistance in plants. Am. Nat. 148: 536–558. [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson, J., G. Dwyer and J. J. Emerson, 2001. Models and data on plant-enemy co-evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35: 469–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, J. R., I. R. Crute and D. D. Clarke, 1993. Variation for virulence in Erysiphe Fischeri from Senecio vulgaris. Plant Pathol. 42: 622–635. [Google Scholar]

- Borghans, J. A. M., J. B. Beltman and R. J. De Boer, 2004. MHC polymorphism under host-pathogen co-evolution. Immunogenetics 55: 732–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. K. M., 2003. A cost of disease resistance: Paradigm or peculiarity? Trends Genet. 19: 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. L., and L. V. Madden, 1990. Introduction to Plant Disease Epidemiology. Wiley Interscience, New York.

- Dangl, J. L., and J. D. G. Jones, 2001. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewit, P., 1992. Molecular characterization of gene-for-gene systems in plant-fungus interactions and the application of avirulence genes in control of plant-pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 30: 391–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinoor, A., and N. Eshed, 1987. The analysis of host and pathogen populations in natural ecosystems, pp. 75–88 in Populations of Plant Pathogens, edited by M. S. Wolfe and C. E. Caten. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

- Frank, S. A., 1992. Models of plant pathogen co-evolution. Trends Genet. 8: 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S. A., 1993. a Co-evolutionary genetics of plants and pathogens. Evol. Ecol. 7: 45–75. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S. A., 1993. b Specificity versus detectable polymorphism in host-parasite genetics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 254: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S. A., 1997. Spatial processes in host-parasite genetics, pp. 325–352 in Metapopulation Biology: Ecology, Genetics and Evolution, edited by I. Hanski and M. Gilpin. Academic Press, New York.

- Hill, A. V. S., 2001. The genomics and genetics of human infectious disease susceptibility. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2: 373–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub, E. B., 2001. The arms race is ancient history in Arabidopsis, the wildflower. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 516–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. D. G., and J. L. Dangl, 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, J. H., 1994. Genetics of powdery mildew resistance in barley. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 13: 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S., J. Boch and U. Bonas, 2005. Characterization of AvrBs3-like effectors from a Brassicaceae pathogen reveals virulence and avirulence activities and a protein with a novel repeat architecture. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18: 838–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, G. C., and J. J. Burdon, 1997. Effects of mutation and random drift on Leonard's gene-for-gene co-evolution model. Phytopathology 87: 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kot, M., 2001. Elements of Mathematical Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Laine, A. L., 2004. Resistance variation within and among host populations in a plant-pathogen metapopulation: implications for regional pathogen dynamics. J. Ecol. 92: 990–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, K. J., 1969. Selection in heterogeneous populations of Puccinia graminis f. sp. avenae. Phytopathology 59: 1845–1850. [Google Scholar]

- May, R. M., and R. M. Anderson, 1990. Parasite host co-evolution. Parasitology 100: S89–S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudgett, M. B., 2005. New insights to the function of phytopathogenic bacterial type III effectors in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56: 509–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, M. M., B. C. Meyers, R. W. Michelmore and B. S. Gaut, 2002. Patterns of positive selection in the complete NBS-LRR gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 12: 1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout, C. J., P. Skamnioti, O. Porritt, S. Sacristan, J. D. G. Jones et al., 2006. Multiple avirulence paralogues in cereal powdery mildew fungi may contribute to parasite fitness and defeat of plant resistance. Plant Cell 18: 2402–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughgarden, J., 1996. Theory of Population Genetics and Evolutionary Ecology: An Introduction. Prentice Hall, New York.

- Salathe, M., A. Scherer and S. Bonhoeffer, 2005. Neutral drift and polymorphism in gene-for-gene systems. Ecol. Lett. 8: 925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, A., 2000. Host-parasite co-evolution in a multilocus gene-for-gene system. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 267: 2183–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra, J., 2005. Stable polymorphisms in a two-locus gene-for-gene system. Phytopathology 95: 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skamnioti, P., and C. J. Ridout, 2005. Microbial avirulence determinants: guided missiles or antigenic flak? Mol. Plant Pathol. 6: 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, E. A., G. Dwyer, R. Mauricio, M. Kreitman and J. Bergelson, 1999. Dynamics of disease resistance polymorphism at the Rpm1 locus of Arabidopsis. Nature 400: 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, A., and J. K. M. Brown, 2007. Stability of genetic polymorphism in host-parasite interactions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 274: 809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrall, P. H., and J. J. Burdon, 2002. Evolution of gene-for-gene systems in metapopulations: the effect of spatial scale of host and pathogen dispersal. Plant Pathol. 51: 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Thrall, P. H., and J. J. Burdon, 2003. Evolution of virulence in a plant host-pathogen metapopulation. Science 299: 1735–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrall, P. H., J. J. Burdon and A. Young, 2001. Variation in resistance and virulence among demes of a plant host-pathogen metapopulation. J. Ecol. 89: 736–748. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, D., M. B. Traw, J. Q. Chen, M. Kreitman and J. Bergelson, 2003. Fitness costs of R-gene-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 423: 74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera Cruz, C. M., J. F. Bai, I. Ona, H. Leung, R. J. Nelson et al., 2000. Predicting durability of a disease resistance gene based on an assessment of the fitness loss and epidemiological consequences of avirulence gene mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 13500–13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, G., and J. Bergelson, 2004. Effector genes of Xanthamonas axonopodis pv. vesicatoria promote transmission and enhance other fitness traits in the field. Genetics 166: 693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram Research, 2003. Mathematica. Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL.