Abstract

In this paper authors present two cases of multiple schwannomas without the features of neurofibromatosis (NF). The authors retrospectively reviewed the hospital charts, radiology films, operative notes and pathology slides of these two patients. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis. The two patients had contrast enhanced MRI, which was negative for vestibular schwannomas. Both underwent surgical excision of symptomatic lesions. Histopathology confirmed these lesions as schwannomas. Molecular genetic analysis in case 1 demonstrated two distinct mutations of the NF2 gene in two different schwannomas, with concomitant loss of heterozygosity in both tumours. In contrast peripheral blood lymphocytes did not reveal mutations of NF2. The authors recommend surgery for symptomatic lesions. Asymptomatic tumours can be monitored. Regular follow up is essential as they may develop fresh lesions at any time. The relevant literature is discussed.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Schwannomatosis, Neurofibromatosis type 1, Neurofibromatosis type 2

Introduction

Schwannomas are benign, slowly growing, encapsulated peripheral nerve tumours. Both schwannomas and neurofibromas originate from the insulating coverings of the nerves. Schwannomas are very homogenous tumours and consist of only schwann cells. They develop on the outside of the nerve, but may push it aside or against adjacent structures causing damage [4]. Neurofibromas are very heterogeneous tumours, which incorporate a mixture of proliferating nerve sheath cells probably arising from perineural fibroblasts [10]. They infiltrate the nerve and displace the individual nerve fibres. Some schwannomas may be cellular and may mimic sarcoma in histological appearance. However, the prognosis is the same as that of benign schwannomas [10, 33]. Most schwannomas occur as solitary lesions and may affect one or more nerves [1–3, 11]. The presence of multiple schwannomas in a single patient suggests tumorogenesis and a possible association with one of the several syndromes, most commonly associated with neurofibromatosis type 2 [7].

Patients with schwannomatosis develop multiple schwannomas on cranial, spinal and peripheral nerves, but they do not develop vestibular schwannomas (VS). They do not develop other tumours such as meninigiomas, ependymomas or astrocytomas [14, 25, 29, 30, 32, 34]. Patients with schwannomatosis usually present with pain [14, 16] whereas NF2 patients present with neurologic deficit [5]. Presence of myxoid stroma, nerve oedema, or an intraneural growth pattern on histology supports the diagnosis of schwannomatosis [24]. Molecular and genetic analysis also suggests that schwannomatosis is a distinct genetic and clinical syndrome [13, 29].

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the hospital charts, operative reports and histopathology of two patients who had two or more pathologically proven schwannomas. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis. Both had Gadolinium enhanced MRI scans of the brain, which revealed no evidence of VS. Ophthalmologic and general examination did not reveal features suggestive of NF2. Both underwent surgery for symptomatic lesions. The overall features of the two patients are presented in Table 1. Literature for review was identified by searching Pub Med.

Table 1.

Patient summary

| No | Age | Sex | Presenting symptoms | Tumour distribution | Clinical findings | Surgery | Pathology | Family history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | M | 1993-Neck swelling | Neck Intradural—L2, T6 | Ophth-exam Nil | 1993-Total excision | Schwannoma | Nil |

| 1998-Backache with radicular pain left leg | No cutaneous markers | 1998-Total excision | Schwannoma | |||||

| 2004-Scapular pain | 2004-Total excision | Schwannoma | ||||||

| 2 | 37 | M | 1994-Back pain and pain in his left thigh | Intradural—L2, L5/S1, T2/3, T11 | Ophth-exam Nil | 1994-Total excision | Schwannoma | Nil |

| 1998-Difficulty in walking and numbness in legs | Cutaneous lumps in axilla, thigh and neck | 1998-Total excision | Schwannoma |

Summary

Case reports

Case 1

A 25-year-old gentleman underwent excision of three schwannomas over a span of 11 years. He first underwent surgery at age 14 for a neck swelling. Histopathology confirmed as schwannoma. He presented in 1998 with backache and radicular pain in his left leg with minimal weakness. MRI scan demonstrated well-defined intradural lesion at L2 enhancing with gadolinium. Cervical and thoracic MRI was normal. He underwent excision of the tumour and histopathology was confirmed as an schwannoma (Fig. 1). Following surgery his pain subsided and the power in the left leg improved to normal. Gadolinium MRI of the lumbar spine at 1 year showed total excision. Cervical, thoracic and cranial MRI were normal. Annual Brain stem auditory evoked potentials were also normal. In 2003 he had MRI of the thoracic spine due to pain in the midthoracic region. MRI scan demonstrated a small enhancing intradural lesion at T6 level. Since the lesion was small with no cord compression, surgery was not advised and he remained under review. In August 2004 he presented with right scapular pain radiating to the mid thoracic level and also pain in the right arm. MRI scan of the thoracic spine showed an increase in the size of the lesion (Fig. 2). He underwent total excision of the intradural lesion. Histopathology confirmed a schwannoma. He did not have any cutaneous markers for neurofibromatosis. Ophthalmologic examination was normal. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis. His cranial MRI was normal. BAEP were normal. NF2 mutation screening results are summarised in Table 2.

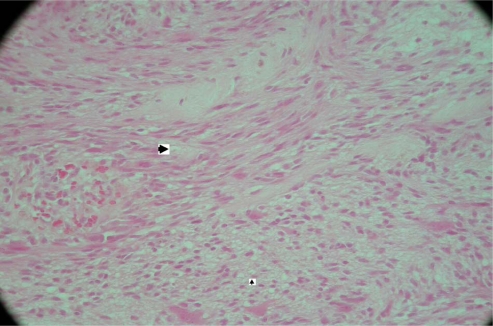

Fig. 1.

Histological examination reveals a tumour composed of schwann cells, which are seen as streams of elongated cells with tapering nuclei. Two main patterns of cellular organisation are clearly seen in this case. The compact areas where cells are arranged in streams (Antoni A)—marked by bigger arrowhead. The smaller arrowhead marks loosely arranged cells with areas of vacuolation and lipidisation (Antoni B). Elsewhere, blood vessels show thickening and hyalinisation of their walls. Mitoses are sparse and the appearances are of a conventional Schwannoma (WHO grade I) (case 1)

Fig. 2.

Thoracic Intradural lesion (case 1)

Table 2.

Case 1 Mutation Screening

| Year | Lymphocyte DNA | Tumour DNA |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | No mutation | Mutation at 379_406 del A in NF2 exon 4 |

| Loss of heterozygostity for NF2CA3 | ||

| 1998 | No mutation | Mutation at nucleotide 441 del G in NF2 exon 4 |

| Loss of heterozygosity for D22S268, D22S275, NF2CA3 |

NF2 mutation screening (case 1)

Case 2

This 37-year-old gentleman presented in 1994 with back pain and pain in his left thigh, of 6 months duration. He had some difficulty with micturition prior to surgery. MRI scan demonstrated an enhancing intradural extramedullary lesion at L2 (Fig. 3). He underwent complete resection of the tumour in March 1994 with a diagnosis of schwannoma. Post surgery he made a good recovery. Postoperative scans after 1 year showed two small intradural lesions at L2 and L5/S1 (Fig. 4). Cranial MRI was normal. These lesions were followed up with yearly MRI studies. He did not have cutaneous or ophthalmologic markers of NF2. BAEPs were also normal. He had a further MRI scan in 1998 when he presented with difficulty in walking and numbness in his legs. MRI scan demonstrated a large enhancing intradural lesion at T2/3 level. He underwent complete resection of this lesion. Histology confirmed a schwannoma (Fig. 5). Post surgery he made an excellent recovery and was able to walk unaided. Postoperative scan a year later showed a small new enhancing intradural lesion at the T11 level (Fig. 6). In 2002 he developed small cutaneous lumps in his right thigh (1 cm) and right axilla (5 mm). In 2004 he developed another small swelling on the left side of the neck lateral to trachea and deep to sternocleidomastoid muscle. His small asymptomatic lesions in thoracic and lumbar spines are being followed with yearly MRI studies. There was no family history of NF1 or NF2.

Fig. 3.

Lumbar Intradural lesion (case 2)

Fig. 4.

Intradural lesions at L2 and L5/S1 (case 2)

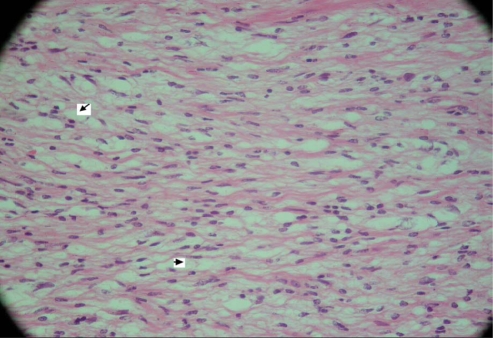

Fig. 5.

This tumour is mainly composed of loose Antoni B tissue. There are small foci of increased cellularity but no definite nuclear palisading is noted. Elsewhere, the tumour contains hyalinised thick-walled blood vessels. Mitotic figures are not seen. The appearances are consistent with a conventional schwannoma (WHO grade I) (case 2)

Fig. 6.

Intradural lesions at T11, L2 and L5/S1

Discussion

Of the several subtypes of neurofibromatosis described in the literature, only neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) have recognised National Institute of Health (NIH) consensus guidelines for diagnosis [18, 19]. NF1 is the most common with an estimated incidence of 1/2500 at birth, representing more than 90% of all neurofibromatosis patients [8, 20, 26]. NF2 arises from sporadic de nova mutations in more than 50% of patients [22]. The NF2 gene was characterised from chromosome 22 q12 [27, 31]. It is a tumour suppressor gene spanning 110 kb and comprises of 16 constitutive exons and one alternative spliced exon [28]. The NF2 gene product is named as merlin. Merlin has structural similarity to a family of proteins that link the actin cytoskeleton to cell membrane glycoprotein [9].

Schwannomatosis was first reported in 1973 as neurofibromatosis type 3 [21]. Multiple cutaneous and spinal schwannomas, without acoustic tumours or other signs of NF1 or NF2, is characteristic. Multiple schwannomas in the same individual may suggest neurofibromatosis type 2 [7]. Two-thirds of NF2 affected individuals will develop schwannomas and they may precede vestibular tumours. Various authors have reviewed reports of individuals with multiple schwannomas who do not show evidence of VS or other features of NF2 [5, 14, 17, 23]. They suggest that schwannomatosis is distinct from other forms of neurofibromatosis.

Evans et al. [6] reported five families with schwannomatosis inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. They had multiple skin and spinal schwannomas without vestibular tumours. Member of a sixth family who initially appeared to have schwannomatosis developed bilateral acoustic neuromas and were later classified as having NF2. He noted difficulty in distinguishing the two disorders and suggested that young patients with multiple schwannomas may have a variant of NF2.

Currently, there are no NIH diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Jacoby et al. [13] proposed clinical criteria for the diagnosis of schwannomatosis. They suggested two or more pathologically proven schwannomas and lack of radiographic evidence of vestibular tumours at age more than 18 years could be taken as evidence of definite schwannomatosis. If MRI of the brain is not available then a probable or presumptive diagnosis may be made if the patient has two or more pathologically proven schwannomas and no clinical symptoms of eighth nerve symptoms at age greater then 30.

Michael et al. [18] proposed modifications that increase the specificity of schwannomatosis diagnostic criteria. According to these authors all patients with definite or possible schwannomatosis must not fulfil any of the existing criteria for NF2 and have no evidence of VS on high quality MRI scan, no first degree relative with NF2 and no constitutional NF2 mutations. The first criterion for definite schwannomatosis is fulfilled if the patient has two or more non-intradermal schwannomas, is older than age 30 years, lacks evidence of VS on high quality MRI scan and does not have a known constitutional NF2 mutation [16]. The second criterion for definite schwannomatosis is fulfilled if an individual has a first degree relative with definite schwannomatosis and has one or more pathologically confirmed non-VS schwannomas, without reference to the patients age, MRI scan results, or results of NF2 mutation testing.

Patients with schwannomatosis represent a very small fraction of patients with spinal or peripheral schwannomas who are managed neurosurgically. Seppala et al. [29] reported an incidence of 3.7% in their series. Haung et al. [12] reported an incidence of 4.6% in their series. These patients commonly undergo multiple operative procedures. They usually present in there fourth decade [12, 29] unlike NF2 patients who present at an earlier age [5]. In this report one patient presented in the second decade and the other in his third decade.

Various authors have studied the molecular genetics of schwannomatosis. Jacoby et al. [13] examined the NF2 locus in 20 unrelated schwannomatosis patients and their affected relatives. They found that the tumours showed typical truncating mutations of the NF2 gene and loss of heterozygosity of the surrounding region of chromosome 22. They found that unlike patients with NF2, no heterozygous NF2 gene changes were seen in normal tissues. In the present report genetic analysis was available for case 1. Lymphocyte DNA did not reveal any NF2 mutation but the tumour DNA showed loss of heterozygosity and mutations of NF2 gene (Table 2). MacCollin et al. [15] studied 28 schwannoma specimens from 17 affected individuals. They identified 20 different somatic mutations in the NF2 gene, 18 of which were truncating mutations. None of the mutations detected in tumour specimens was detected in paired blood specimens. No tumours were found to have two mutations in the NF2 gene. He concluded that schwannomatosis is a distinct entity from neurofibromatosis 2 and that the NF2 region is not the genetic locus responsible for familial schwannomatosis.

Conclusions

Schwannomatosis is a disorder distinct from neurofibromatosis. Most symptomatic schwannomas can be removed surgically. Asymptomatic tumours can be monitored conservatively with serial MRI studies, usually at a yearly interval. It is important to consider genetic testing. Molecular diagnosis rules out NF2 and appropriate genetic counseling can be offered. Patients are advised to monitor themselves for any new neurological problems. Regular and long-term follow up is essential as they may develop fresh lesions at any time

References

- 1.Barre PS, Shaffer JW, Carter JR, et al. Multiplicity of neurilemmomas in the upper extremity. J Hand Surg (Am) 1987;12:307–311. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daras M, Koppel BS, Heise CW, et al. Multiple spinal intradural schwannomas in the absence of Von Recklinghausens disease. Spine. 1993;18:2556–2559. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199312000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donner TR, Voorhies RM, Kline DG. Neural sheath tumours of major nerves. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:362–373. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.3.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW (1988) Soft tissue tumours, 2d edn. Mosby, St. Louis, pp 724–815

- 5.Evans DGR, Huson SM, Donnai D, et al. A clinical study of type 2 neurofibromatosis. Q J Med. 1992;84:603–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans DGR, Mason S, Huson SM, et al. Spinal and cutaneous Schwannomatosis is a variant form of type 2 neurofibromatosis: a clinical and molecular study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:361–366. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutman DH. Molecular insights into neurofibromatosis 2 gene. Neuro Biol Dis. 1997;3:247–261. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutman DH. The neurofibromatosis: when less is more. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:747–755. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutman DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, et al. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haariada S, Nerlich AG, Bise K, et al. Comparison of various basement membrane components in benign and malignant speripheral nerve tumours. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;421:331–338. doi: 10.1007/BF01660980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliday AL, Sobel RA, Martuza RL. Benign spinal nerve sheath tumours: their occurrence sporadically and in neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:248–253. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.2.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang JH, Simon SL, Seema Nagpal SB, et al. Management of patients with Schwannomatosis: report of six cases and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacoby LB, Jones D, Davis K, et al. Molecular analysis of NF2 tumour suppressor gene in Schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1293–1302. doi: 10.1086/301633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacCollin M, Woodfin W, Kronn D, Short MP. Schwannomatosis: a clinical and pathologic study. Neurology. 1996;46:1072–1079. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacCollin M, Willet C, Heinrich B, et al. Familial Schwannomatosis. Exclusion of the NF2 locus as the germ line event. Neurology. 2003;60:1968–1974. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000070184.08740.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacCollin M, Chicocca EA, Evans DG, et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2005;64:1838–1845. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163982.78900.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mautner VF, Tatagiba M, Guthoff R, Samii M, Pulst SM. Neurofibromatosis in the pediatric age group. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:92–96. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michael EB, Friedman JM, Gareth D, Evans R. Increasing the specificity of diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2006;66:730–732. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201190.89751.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvihill JJ, Parry DM, Shermann JL, et al. NIH conference. Neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. An update. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:39–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NIH (1988) Neurofibromatosis, Conference statement, National institutes of health consensus development conference. Arch Neurol 45:575–578 [PubMed]

- 21.Nimura M. Neurofibromatosis. Rinsho Derma. 1973;15:653–663. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry DM, Eldridge R, Kaiser Kupfer M, Bouzas EA, Pikus A, Patronas N. Neurofibromatosis 2: clinical characteristics of 63 affected individuals and clinical evidence for heterogenecity. Am J Genet. 1994;52:450–461. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320520411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parry DM, MacCollin M, Kaiser-Kupfer MI, et al. Germ line mutations in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene: correlation with disease severity and retinal abnormalities. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:529–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poliani PL, DeSantis S, Bettensky RA et al (2005) Defining histologic criteria for the diagnosis of schwannomatosis, Aspen, CO, June 5–8

- 25.Purcell SM, Dixon SL, Schwannomatosis (1989) An unusual variant of neurofibromatosis or a distinct clinical entity. Arch Dermatol 125:390–393 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112313052704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouleau GA, Merel P, Lutchman M, et al. Alteration in new gene encoding a putative membrane-organizing protein causes neurofibromatosis 2. Nature. 1993;363:515–521. doi: 10.1038/363515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruggieri M. The different forms of neurofibromatosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:295–308. doi: 10.1007/s003810050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seppala MT, Saino MA, Haltia MJ, et al. Multiple schwannomas: Schwannomatosis or neurofibromatosis 2. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:36–41. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.1.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin KH, Moon SH, Suh JS, et al. Multiple neurilemomas. A case report. Clin Orthop. 1998;171:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trofatter JA, Mac Collin MM, Rutter JL, et al. A novel moesin-, ezrin-, radixin-like gene is a candidate for the neurofibromatosis 2 suppressor. Cell. 1993;72:791–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90406-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolkenstein P, Benchikhi H, Zeller J, et al. Schwannomatosis: a clinical entity distinct from neurofibromatosis 2. Dermatology. 1997;195:228–231. doi: 10.1159/000245948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodruff JM, Godwin TA, Erlandson RA, et al. Cellular schwannoma: a variety of schwannoma some times mistaken for malignant tumour. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:733–744. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto T, Maruyama S, Mizuno K. Schwannomatosis of sciatic nerve. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:109–113. doi: 10.1007/s002560000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]