Abstract

Diepoxybutane (DEB) is the most potent metabolite of the environmental chemical 1, 3-butadiene (BD), which is prevalent in petrochemical industrial areas. BD is a known mutagen and human carcinogen, and possesses multi-systems organ toxicity. We recently reported that DEB-induced cell death in TK6 lymphoblasts was due to the occurrence of apoptosis, and not necrosis. In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms responsible for DEB-induced apoptosis in these cells. Bax and Bak were found to be over-expressed and activated, and the mitochondrial trans-membrane potential was attenuated in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis. Cytochrome c was depleted from the mitochondria of TK6 cells undergoing apoptosis, and was released into the cytosol in Jurkat-T lymphoblasts exposed to the same concentrations of DEB. Executioner caspase 3 was deduced to be activated by initiator caspase 9. DEB induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, and the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine effectively blocked DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 cells. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is activated to mediate DEB-induced apoptosis in human TK6 lymphoblasts. These results further demonstrate that DEB-induced apoptosis is also mediated by the DEB-induced generation of ROS. This is the first report to examine the mechanism of DEB-induced apoptosis in human lymphoblasts.

Keywords: Diepoxybutane, butadiene, apoptosis, mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, human TK6 lymphoblasts, reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress, N-acetyl-l-cysteine

1. Introduction

Diepoxybutane (DEB) is the most toxic metabolite of 1, 3-butadiene (BD). BD (CH2=CH-CH=CH2, CAS No. 106-99-0) is a high production volume industrial chemical, largely produced through the processing of petroleum, and extensively used in the manufacture of synthetic rubber, polymers, and plastics (NTP, 2005). Exposure to BD occurs principally in the occupational settings of industrial facilities that produce and use this compound (Jackson et al., 2000; Anttinen-Klemetti et al., 2006). However, exposure to low levels of BD in urban air and in door settings do occur, since BD is also found in automobile exhaust and cigarette smoke (Adam et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2007). BD is currently regulated as a hazardous air pollutant (NTP, 2005).

BD is a mutagen, and is classified by the National Toxicology Program as a known human carcinogen (NTP, 2005). The toxicity of BD, however, is mediated through its epoxy metabolites, 1, 2-epoxy-3-butene (EB), 1,2:3,4-diepoxybutane (DEB), and 1,2-dihydroxy-3,4-epoxybutane (EBD). Although all three metabolites are genotoxic, carcinogenic and mutagenic, and induce chromosomal aberrations, micronucleus formation, sister chromatid exchanges, and mutations in various animal and human cells, DEB is the most potent (Kligerman and Hu, 2006). DEB is a bi-functional alkylating agent that exhibits both inter-strand and intra-strand DNA cross-linking ability (Millard et al., 2006). DEB also generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can damage DNA or produce H2O2 (Erexson and Tindall, 2000a). Although DEB is cytotoxic, the cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating this process are not completely understood. In a recent study, we reported that the DEB-induced cell death in human TK6 lymphoblasts exposed to low concentrations of DEB was due to the occurrence of apoptosis, and not necrosis (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004). Apoptosis in response to DEB exposure has also been observed in the Big Blue Rat cultured cells, mouse L929 cultured cells, as well as in human CD34+ bone marrow cells (Erexson and Tindall, 2000b; Irons et al., 2000; Brockmann et al., 2006). The molecular mechanisms by which DEB induces apoptosis, however, have not yet been elucidated.

Apoptosis is a highly ordered cellular suicidal mechanism that regulates normal physiological processes (such as development and immune function), and plays a crucial role in maintaining normal homeostasis by eliminating aged, damaged, and cancerous cells from the system (Hail et al., 2006). It is characterized by distinct morphological and biochemical changes in the nucleus, as well as in the cell membrane and cytoplasm. Morphological changes in the nucleus include condensation/margination of chromatin, DNA fragmentation in a laddering pattern, and nuclear fragmentation. Apoptotic cells are also characterized by the externalization of phosphatidyl-serine (PS), cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, a peculiar boiling action of the plasma membrane (zeiosis), and fragmentation of the cell into apoptotic bodies (Vermeulen et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005).

Apoptosis in response to cellular stress may be executed through two well known principal pathways that lead to the activation of effector caspases, the central event in the effector phase of apoptosis (Jin and El-Deiry, 2005; Vermeulen et al., 2005). The extrinsic apoptosis pathway is initiated through ligation of death receptor family receptors by their ligands (Fas et al., 2006). The intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway is triggered by stress stimuli, including growth factor deprivation, DNA damage, and oxidative stress (Mohamad et al., 2005). This pathway is regulated by the pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bad, Bak, Bim, t-BID) and anti-apoptotic (such as Bcl-2) Bcl-2 family proteins, which induce or prevent, respectively, the release of apoptogenic factors from the mitochondrial inter-membrane space into the cytosol (Mohamad et al., 2005; Er et al., 2006). Execution of apoptosis through this pathway involves increased permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, resulting in the release of apoptosis promoting proteins [such as cytochrome c, SMAC/DIABLO, and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF)] from the mitochondrial inter-membrane space. The release of mitochondrial cytochrome c facilitates the formation of the apoptosome complex (composed of cytochrome c, the adapter molecule apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (APAF1) and pro-caspase 9), which then leads to the activation of caspase 9 by cleavage, subsequently activating the effector caspases, such as caspases 3, 6, and 7 (Jin and El-Deiry, 2005; Wang et al., 2005), which execute the final stages of apoptosis.

In recent years, evidence has accumulated to indicate that oxidative stress may play a role in the regulation of apoptosis (Curtin et al., 2002). Oxidative stress occurs when the antioxidant systems are overwhelmed by increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). An increase in cellular ROS generation has been observed in apoptotic processes triggered by various toxicants in various cell types (Buttke and Sandstrom, 1994). Although, oxidative stress has been implicated in DEB-induced cytotoxicity (Pagano et al., 2003), there have been no reports to indicate whether oxidative stress plays a role in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis in exposed cells.

The mechanisms mediating apoptosis cannot be predicted, for they are toxicant and cell type dependent (Hail et al., 2006; Modjtahedi et al., 2006). Thus, in this study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms responsible for DEB-induced cytotoxicity by examining the role of the mitochondrial pathway in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis in human TK6 lymphoblasts. The involvement of the mitochondrial pathway was deduced by examining the occurrence of several rate-limiting steps of this pathway in TK6 lymphoblasts undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis. The role of oxidative stress in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 cells was also examined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

DEB (11.267 M) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Company. Acridine-orange (AO, 10 mg/ml), ethidium-bromide (EB, 10 mg/ml), Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Cat # P36931) and CM-H2DCFDA (5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2’,7’-dichlorodihyrofluorescein diacetate) were purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. The caspase inhibitor Z-LEHD-FMK was purchased from MBL International, Inc. as a 2 mM sterile solution. N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) was purchased from Calbiochem, Inc. All manipulations were performed under class 2 type B3 conditions, since most of these chemicals are hazardous.

2.2. Antibodies

Antibodies directed against the active forms of Bax (N-20) and Bak (AM03) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and EMD Biosciences, Inc, respectively. A monoclonal antibody against cytochrome c oxidase complex IV (COX IV, Cat. # 4850), as well as an antibody specific for the cleaved form of caspase 3 (Cat. # 9661) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. The mouse monoclonal antibodies against cytochrome c utilized for immunofluorescence (clone 6H2.B4) and western blot analysis (Cat # MSA06) were purchased from BD Biosciences, Inc, and Mitosciences, Inc, respectively. Alexa Flour® 488-anti-COX IV (Cat. # A21296), and Alexa Flour® 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody were obtained from Molecular Probes. Anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (GAPDH, MAB374) was purchased from Chemicon, Inc. The secondary (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit) antibodies purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories were utilized at 1:5000 dilution.

2.3. Exposure of cells to diepoxybutane

The human B lymphoblastic cell line TK6 (American Type Culture collection) was propagated at 2 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen Life Technologies), 2 mM l-glutamine and penicillin-streptomycin. The human T-cell line Jurkat was also obtained from the American Type Culture collection, and was propagated in RPMI 1640 medium at 2 × 105 cells/ml, according to vendor instructions. Cells were passaged into fresh media at 24 h prior to each experiment. Cells were then washed, seeded in fresh media, and exposed to DEB stock solutions prepared in media (such that the final vehicle concentration was 0.1%). Exposures to DEB in the presence of caspase inhibitors or N-acetyl-l-cysteine were performed by pre-treating cells with either vehicle or inhibitor for 1 h prior to the addition of DEB or vehicle; the final vehicle concentration was 0.1%.

2.4. Quantitation of diepoxybutane-induced apoptosis

This was performed by assessing nuclear morphology using dual staining with acridine orange and ethidium bromide, as previously described (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004).

2.5. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004). Antigen levels were detected by utilizing a chemi-luminescent substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) and a Fluorichem 8000 Chemifluorimager (Alpha Innotech). Quantitation of the bands was performed by densitometry tracing using the AlphaEase™ software.

2.6. Assessment of mitochondrial trans-membrane potential

Changes in mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ψm) after exposure of TK6 cells to DEB were assessed by utilizing the Mitocapture Apoptosis Detection kit (EMD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mitocapture reagent, a cationic dye, accumulates and forms aggregates in the mitochondria, giving off a bright red fluorescence in healthy cells that maintain their mitochondrial ψm. On the contrary, cells with altered mitochondrial ψm generate cytoplasmic green fluorescence, since the dye fails to accumulate in the mitochondria, and remains in the cytoplasm in its monomeric green form. Samples were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy, utilizing fluorescein (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 520 nm) and rhodamine (excitation at 550 nm, emission at 565 nm) filters. In order to quantitate green and red fluorescence, samples were also analyzed at the indicated wavelengths by utilizing a Molecular Devices fluorescence micro-plate reader.

2.7. Immunofluorescence detection of activated Bax, activated Bak, and cytochrome c

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described, with minor modifications (Kandasamy et al., 2003). Briefly, cells were harvested, and washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for an additional 5 minutes. Cells were subsequently washed in PBS, and incubated in blocking buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS, 1 μg/ml appropriate control IgG, 0.1% sodium azide) for 1 h. Cells were then washed (with PBS containing 2% FBS, 0.1% sodium azide) and incubated with primary antibody {mouse anti-cytochrome c antibody (6H2.B4, 2 μg/ml), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax (N-20), or mouse anti-Bak (AM03)} for 1 h; control cells were incubated with appropriate control rabbit or mouse IgG. The antibody was removed by washing, and the cells were further incubated with an Alexa Flour® 594-labeled appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h. After washing to remove unbound secondary antibody, cells were incubated with an Alexa Flour® 488-labeled anti-COX IV antibody for an additional hour. Cells were stained with 4’, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg/ml in PBS) or Prolong Gold Anti-fade reagent with DAPI to visualize nuclei. Stained cells were analyzed utilizing a Nikon E400 fluorescent microscope equipped with a Diagnostic Instruments RT-Spot Slider digital camera to detect cytochrome c, activated-Bax, activated-Bak, mitochondrial marker COX IV and cell nuclei.

2.8. Sub-cellular fractionation of cell lysates

All manipulation steps were carried out at 4°C. Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were prepared as described previously (Mihara and Moll, 2003), with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were harvested and re-suspended in buffer A (10 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 68 mM sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 0.1% BSA), supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.1 mM leupeptin). After 30 min incubation on ice, cells were disrupted with a dounce homogenizer (25-40 strokes with pestle B), and the homogenates were centrifuged at 200g for 2 min to eliminate unbroken cells. The 500g supernatants were then centrifuged at 7,000g for 15 min to obtain the heavy membrane pellet enriched with mitochondria. The resultant supernatants pre-cleared at 16,000g for 30 min were collected as the cytosolic fractions. Mitochondrial fractions were subsequently solubilized in TBSTDS (10 mM Tris, [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS, 0.02% NaN3, 0.0004% NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.1 mM leupeptin). All fractions were stored at −70 °C until used.

2.9. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species

TK6 cells were pre-incubated with vehicle or 20 mM NAC for 1 hr prior to treatment of cells with 0, 10, or 20 μM DEB for indicated times. Cells were washed three times, and incubated for 20 min in Dulbecco’s PBS (PBS) containing 5 μM of the ROS-sensitive cell-permeable probe CM-H2DCFDA, according to vendor instructions. To determine the total number of cells by nuclear staining, and to identify apoptotic cells by their nuclear morphology, Hoechst 33342 (4 μg/ml final concentration) was included in the reactions containing CM-H2DCFDA. Cells were then washed two times with PBS, and the induction of ROS was examined by fluorescence microscopy. For statistical analysis, the percentage of ROS-positive (green) cells from four different fields was averaged.

3. Results

3.1. Bax and Bak proteins are up-regulated and activated in lymphoblasts undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis

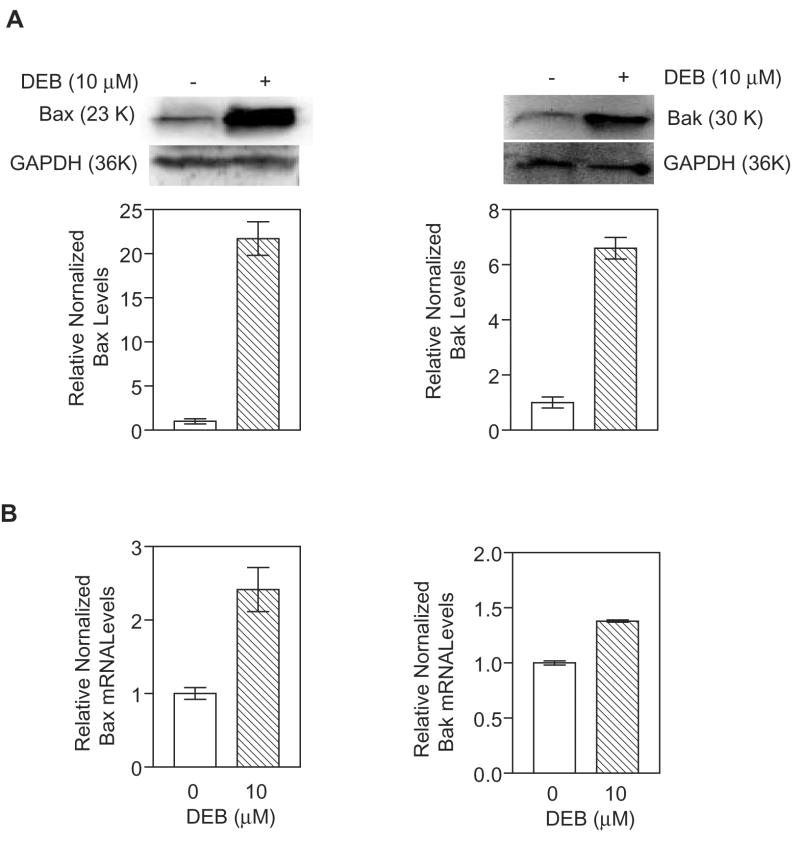

Exposure of TK6 cells to 10 μM and 20 μM DEB for 24h triggers apoptosis in 30% and 50% of the cells, respectively (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004). To understand the mechanism of apoptosis, we examined the regulation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl2 factors Bax and Bak at the protein and mRNA levels in control and TK6 cells exposed to 10 μM DEB for 24 h (Figure 1). Under conditions where GAPDH levels remained unchanged, Bax (panel A, left) and Bak (panel A, right) protein levels were elevated 21.5-fold and 6-fold, respectively, in TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis as compared to control-unexposed cells. Bax steady-state mRNA levels (panel B, left) were consistently found to be elevated approximately 3-fold in exposed cells as compared to control cells, while Bak steady-state mRNA levels (panel B, right) were not significantly elevated under these conditions. These results imply that up-regulation of Bax and Bak proteins in cells exposed to 10 μM DEB for 24 h occurs predominantly at the protein level. Since pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak are known to exert their effects by acting on the mitochondria, the observed up-regulation of the Bax and Bak proteins in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis suggested that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in these cells could be activated.

Figure 1. Bax and Bak protein and mRNA levels in TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis.

A. Protein Levels. Extracts (100 μg of protein) from cells exposed to vehicle and 10 μM DEB for 24 h were subjected to western blot analysis. Relative normalized levels shown in graphical representations for Bax (left panel) and Bak (right panel) were obtained after densitometer tracing, followed by normalization to the corresponding GAPDH levels for each sample. Representatives of three experiments are shown. B. Messenger RNA Levels. Total RNA extracted from control and TK6 cells exposed to 10 μM DEB for 24 h was subjected to quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction using Bax (left panel) and Bak (right panel) gene specific primers. The results obtained were normalized against GAPDH levels in the same samples, and the numbers obtained for exposed cells were compared to control un-exposed cells using a computer program for relative quantitation.

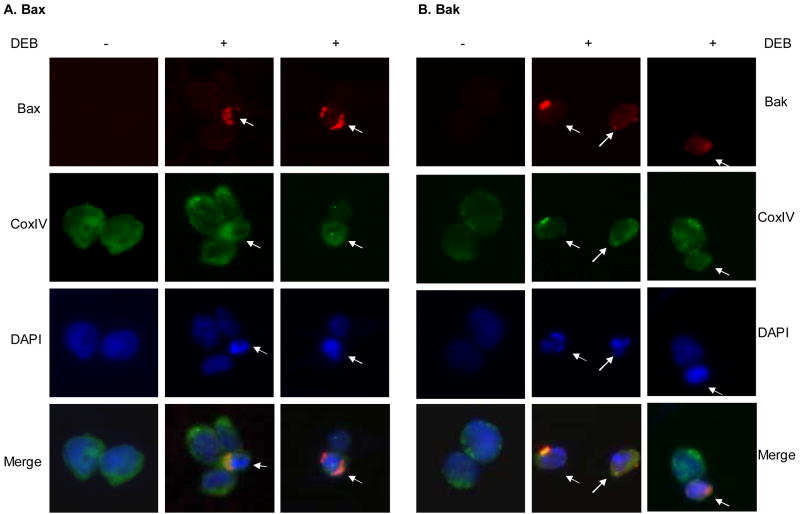

Activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway requires activation and translocation of the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and/or Bak to the mitochondria. To investigate whether the Bax and Bak proteins in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis were activated and translocated to the mitochondria, control and cells exposed to 10 μM DEB for 14 h were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining, using antibodies specific for Bax and Bak in active conformation (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence staining for Bax (panel A, red) and Bak (panel B, red) were detected only in DEB-exposed cells undergoing apoptosis (as shown by the differential blue DAPI staining marked by arrows). The detected Bax and Bak immunostaining co-localized with the cytochrome c oxidase complex IV (COX IV) mitochondrial marker (green) in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis(marked by arrows), as shown by the yellow or orange colors in the respective merged images. These results demonstrate that Bax and Bak proteins in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis are localized to the mitochondria, where they are in active conformation. Collectively, the results shown in figures 1 and 2 suggest that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is activated in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis.

Figure 2. Localization of activated Bax and Bak proteins in TK6 cells after DEB treatment.

Cells were exposed to vehicle or 10 μM DEB for 14 h, fixed, permeabilized, and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies specific for Bax (panel A, red) and Bak (panel B, red) proteins in active conformation. Mitochondrial identification was performed by staining with an Alexa-Fluor 488-conjugated mouse antibody against the mitochondria marker CoxIV (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Fluorescence from the various samples was detected by using a Nikon E400 fluorescence microscope. The same microscopic field for each sample was analyzed for all three fluorochromes, and an overlay of all three microscopic fields is also shown (as merge). Arrows point to cells undergoing early stage DEB-induced apoptosis, as identified by their condensed nuclei after DAPI staining.

3.2. Mitochondrial trans-membrane potential is attenuated in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis

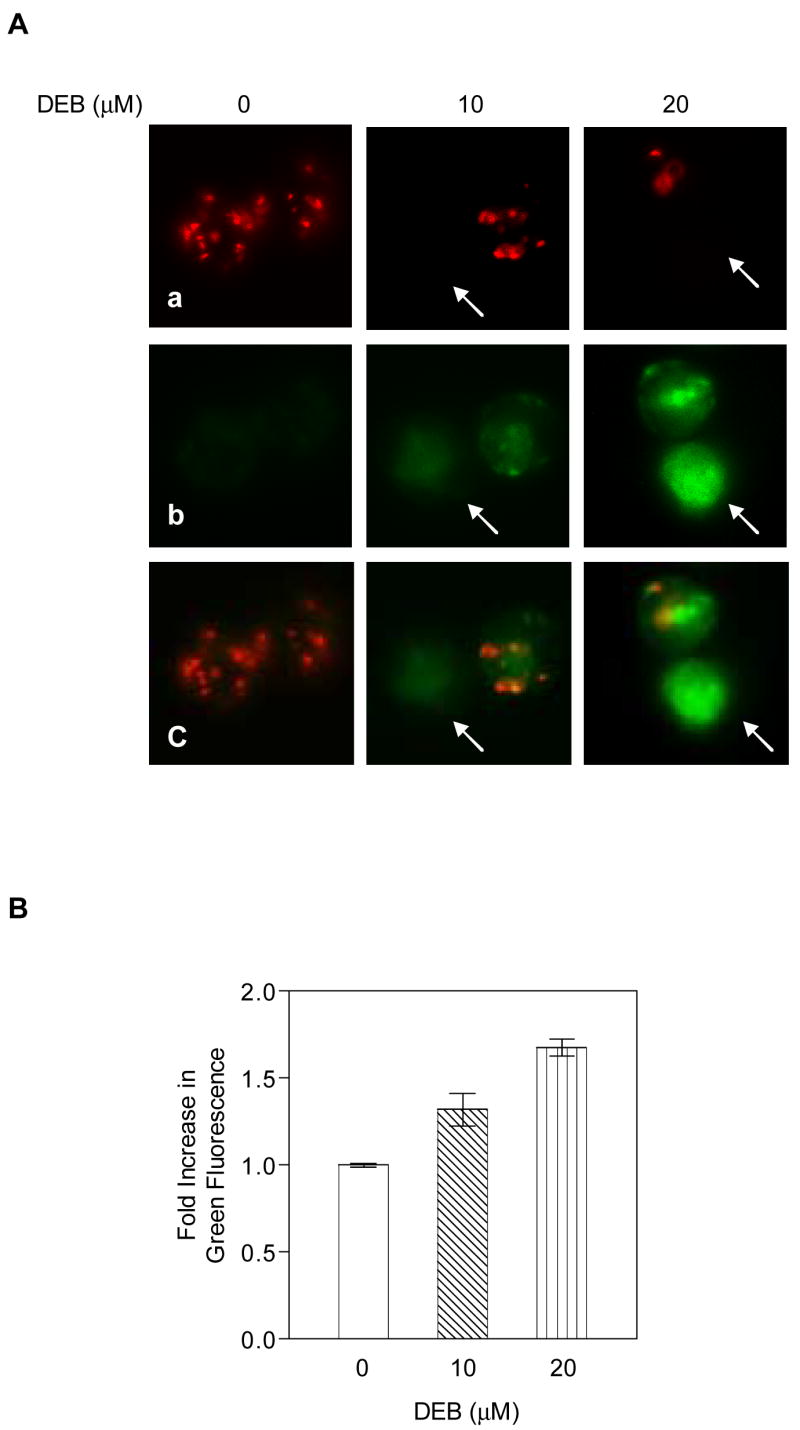

To further investigate the activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by DEB, the effect of DEB exposure on the mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ψm) of exposed TK6 cells was investigated. Cells were treated with vehicle alone, 10 μM, or 20 μM DEB for various times (6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 h). Control and DEB-exposed cells were then stained using the Mitocapture Apoptosis Detection kit (see Methods section for details), and changes in ψm were assessed by fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence microplate reader (Figures 3A-B). The Mitocapture dye reagent exhibits dual fluorescence emission depending on the status of ψm. Panel A shows a representative of the fluorescence microscopy photographs taken at 10 h post-DEB exposure, an optimal time point for changes in ψm between control, 10 μM and 20 μM DEB-exposed cells. Control unexposed cells displayed bright red fluorescence with little green fluorescence. Exposure of cells to DEB progressively decreased the red fluorescence and increased the green fluorescence, as the concentration of DEB increased from 0 μM to 20 μM. Prevalence of green fluorescence occurs when the dye fails to aggregate as a dimer in the mitochondria (due to loss of ψm), and remains in the cytoplasm in monomeric form. Although less than 12% and 20% of the cells exposed to 10 μM and 20 μM DEB, respectively, were apoptotic at 10 h post-DEB exposure, the observed normalized increase in green fluorescence of total cells was quantifiable by a fluorescence plate reader, and this increase directly correlated with DEB concentration (Figure 3B). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the ψm is maintained in control-unexposed cells and attenuated in TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis. These results thus confirm that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is activated by DEB, and may mediate DEB-induced apoptosis in human lymphoblasts.

Figure 3. The mitochondrial trans-membrane potential (ψm) is attenuated in DEB-exposed cells.

TK6 cells exposed to vehicle alone, 10, and 20 μM DEB for various time periods (6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 h) were evaluated for changes in the mitochondrial trans-membrane potential, as described in Methods. The experiment was repeated three times. A. Representative fluorescence microscope images of the same microscopic field obtained at 10 h post-DEB exposure. Images are shown as a, b, c for each sample (at a 40X magnification). a. Images obtained using the rhodamine filter, demonstrating aggregation of the cationic dye in the mitochondria for cells which maintain the mitochondria membrane potential. b. Images obtained using the fluorescein filter, demonstrating the failure of the cationic dye to accumulate in the mitochondria, remaining in the cytoplasm in its monomeric green form. c. A merge of fluorescein and rhodamine images for each sample. B. Quantitation of changes in mitochondria transmembrane potential. The samples analyzed by fluorescence microscopy were also analyzed using a fluorescence micro-plate reader. The ratio for green fluorescence to red fluorescence for each DEB-exposed sample was normalized against the corresponding ratio for the control untreated sample, and the results were plotted as a fold increase in green fluorescence against increasing DEB concentrations utilized for exposure.

3.3. Diepoxybutane affects the distribution of cytochrome c levels in exposed cells

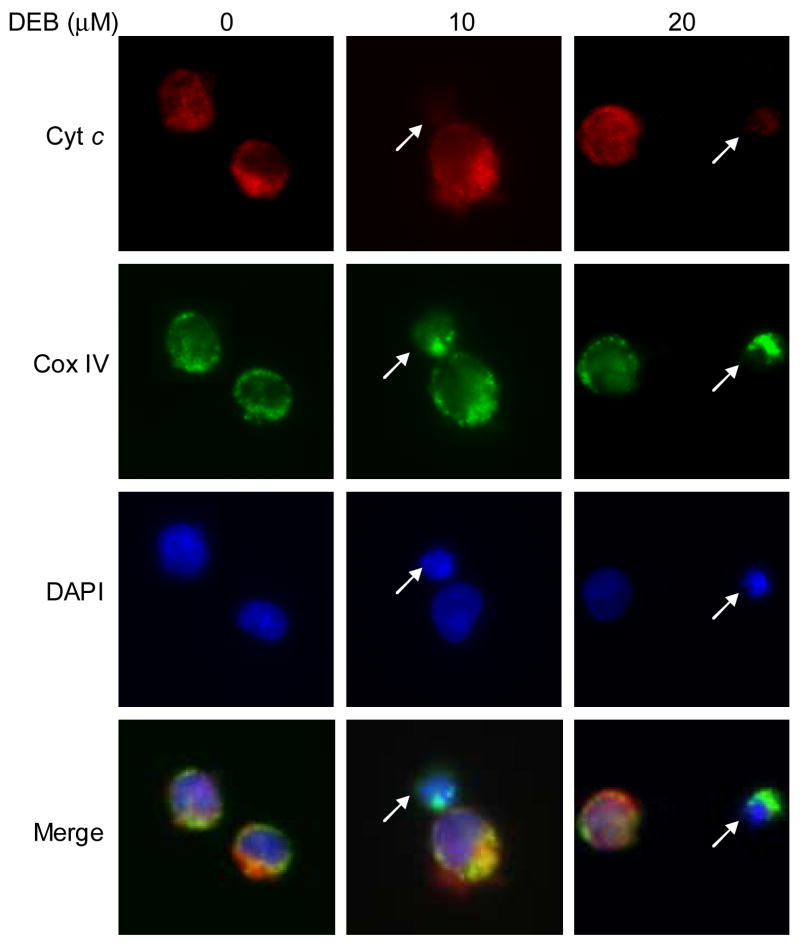

To further confirm the role of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis, the distribution of cytochrome c within TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis was examined. TK6 cells were exposed to vehicle or 10 μM DEB for 14h (time post-DEB exposure with maximum alterations in mitochondrial ψm for cells exposed to 10 μM DEB), and cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. As shown in figure 4, cytochrome c (red) was found to co-localize with the COX IV mitochondrial marker (green) in control unexposed cells, resulting in a predominantly yellow/orange overlay (see merged image). In contrast, in TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis (as demonstrated by the condensed nuclei identified by DAPI staining and marked by arrows in the DEB-exposed panels), there was considerably less or no detectable cytochrome c (red), although mitochondrial staining (green) was still detected. Consequently, there is a dramatic reduction in the yellow overlay color in cells undergoing early apoptosis (see merged images marked by arrows), due to the lack of co-localization of cytochrome c (red) with the COX IV mitochondrial marker (green). Since cytochrome c is a mitochondria resident protein, these results suggest that DEB causes the depletion of cytochrome c from the mitochondria of TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis.

Figure 4. Immunofluorescence detection of cytochrome c release in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis.

TK6 cells were exposed to vehicle alone or 10 μM DEB for 14 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for cytochrome c (red, using mouse anti-cytochrome c antibody 6H2.B4 and Alexa-Fluor® 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody), the mitochondrial marker COX IV (green, using Alexa-Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-COX IV antibody), and for the location and morphology of nuclei using DAPI staining (blue). Fluorescence from the various samples was detected by using a Nikon E400 fluorescence microscope equipped a Diagnostic Instruments RT-Spot slider digital camera. The same microscopic field for each sample was analyzed for all three fluorochromes, and an overlay of all three microscopic fields is also shown. Arrows point to cells undergoing early stage DEB-induced apoptosis.

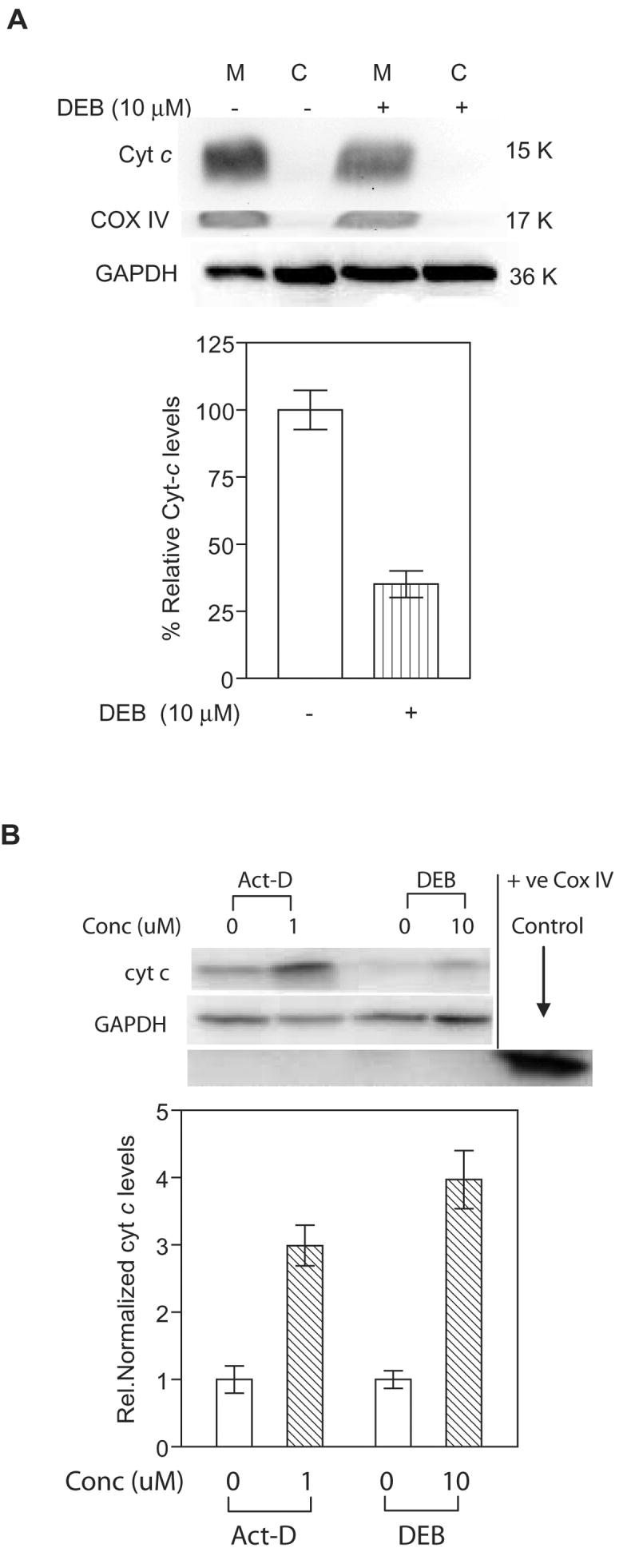

To further confirm the observed results on the depletion of cytochrome c from the mitochondria of TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis, TK6 cells were exposed to vehicle or 10 μM DEB for 14h, and cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were analyzed for cytochrome c, COX IV (mitochondrial marker), and GAPDH levels by western blot analysis (Figure 5A, upper panel). As shown in the graphical representation of the results (Figure 5A, lower panel), only 35% of the cytochrome c levels detected in the mitochondrial fraction of control un-exposed cells was detected in the mitochondrial fraction of exposed cells; under these conditions, levels of the mitochondrial marker COX IV remained unchanged in exposed cells as compared to control unexposed cells. Cytochrome c levels were repeatedly undetectable in the cytosolic fractions of control and DEB-exposed TK6 cells under our experimental conditions (tested up to 24 h post-DEB-exposure and 20 μM DEB). To demonstrate that the inability to detect the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol of TK6 cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis was not due to experimental artifacts, a positive control system composed of Jurkat cells exposed to vehicle only or 1 μM of actinomycin-D was utilized, and mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were analyzed by western blot analysis (Figure 5B). Cytochrome c levels increased three fold in the cytosolic fraction of actinomycin D-exposed cells as compared to control un-exposed cells, confirming the fact that the experimental conditions being utilized were capable of detecting the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol. In fact, under conditions where GAPDH levels remained unchanged, exposure of Jurkat cells to 10 μM DEB for 17 h resulted in a four fold increase in cytosolic cytochrome c levels as compared to control un-exposed cells (Figure 5B). Collectively, the results of figures 4 and 5 imply that DEB caused the depletion of cytochrome c from the mitochondria of exposed TK6 cells, without a detectable increase in cytosolic cytochrome c levels under all the experimental conditions tested. These results also demonstrate that DEB caused the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytosolic fraction of exposed Jurkat cells, which are T-lymphoblastic cells that undergo apoptosis at approximately half the frequency of TK6 cells under identical DEB concentrations. These results thus imply that the induction of different patterns of cytochrome c distribution/release occur in a cell type-specific manner. The basis of these differences is currently under investigation, and will be published elsewhere. Nevertheless, since cytochrome c is a mitochondrial protein, these results further strengthen the so far observed influence of DEB upon the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.

Figure 5. DEB affects the distribution of cytochrome c levels in exposed cells.

Mitochondrial (M) and cytosolic (C) fractions from control and DEB-exposed cells were analyzed for cytochrome c (using 7H8.2C12 antibody), mitochondrial marker COX IV, and GAPDH levels by western blot analysis. The experiments were repeated three times, and representative western blot data as well as the corresponding bar graph of the relative normalized cytochrome c levels are shown. A. TK6 cells exposed to 10 μM DEB for 14 h. Western blot data (top panel) obtained from mitochondria and cytosolic fractions, as well as the graphic representation (bottom panel) of mitochondrial cytochrome c levels in control and DEB-exposed TK6 cells are shown. Percent relative cytochrome c (Cyt-c) levels were obtained by normalizing against COX IV levels in the same fraction, and expressing this value as a percentage of Cyt-c levels in the mitochondria of control unexposed cells. Since no cytochrome c was detected in cytosolic fractions of TK6 cells under our experimental conditions, only mitochondrial Cyt-c values in control and exposed cells are compared (bottom panel). B. Jurkat cells exposed to 1 uM Actinomycin D and 10 μM DEB for 17 h. Western blot data (top panel) as well as the graphic representation (bottom panel) of cytochrome c levels in the cytosolic fractions of control and exposed cells are shown. Relative normalized cytochrome c (Cyt-c) levels were obtained by normalizing against GAPDH levels in the same sample, and further normalizing the obtained values against the corresponding control un-exposed cell values.

3.4. Activation of caspase 3 occurs downstream of caspase 9 in diepoxybutane-induced apoptosis

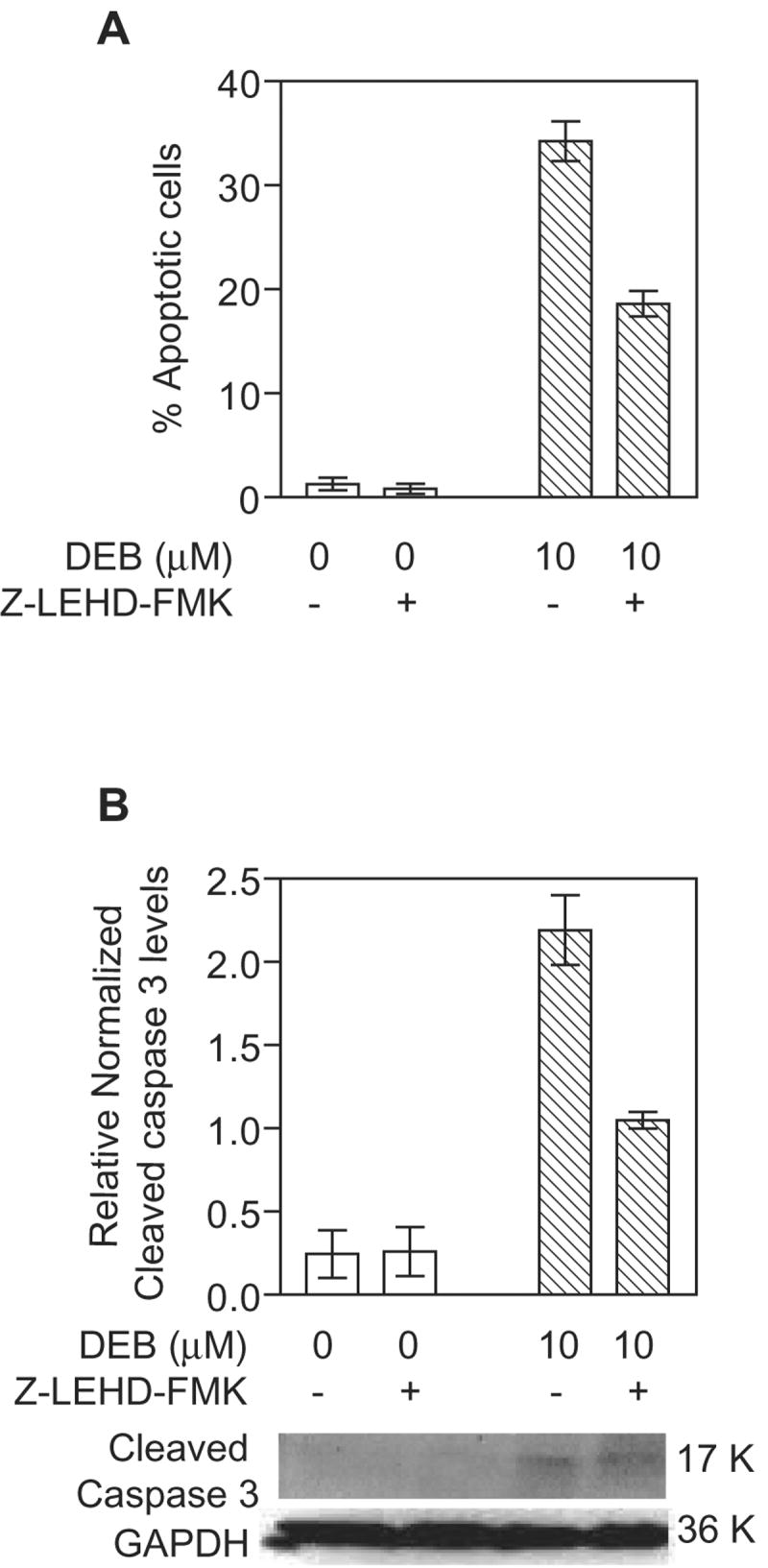

Since the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway was found to be activated in TK6 lymphoblasts undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis, we examined whether executioner caspase 3 serves as a downstream substrate for mitochondrial apoptotic pathway initiator caspase 9. TK6 cells pre-treated with DMSO or 2 μM of the caspase 9 inhibitor Z-LEHD-FMK for 1 h were exposed to vehicle alone or 10 μM DEB for 24 h (Figure 6). Samples were then analyzed for apoptosis by nuclear morphology fluorescent dye staining (panel A) as well as for activated (cleaved) caspase 3 by western blot analysis (panel B). DEB-induced apoptosis was found to be inhibited by approximately 50% in the presence of the caspase 9 inhibitor. Likewise, under conditions where GAPDH levels remained unchanged, the DEB-dependent activation (cleavage) of caspase 3 was inhibited by approximately 50% in cells exposed to 10 μM DEB in the presence of the caspase 9 inhibitor as compared to exposed cells without the inhibitor (panel B). No cleaved caspase 3 band was observed in control un-exposed cells. Since the specific inhibitor of caspase 9 suppressed DEB-induced apoptosis as well as the activation (cleavage) of caspase 3 in the same cells, these results imply that caspase 3 activation in DEB-induced apoptosis occurs downstream of caspase 9 activation. These results further support the involvement of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis.

Figure 6. Activation of caspase 3 in DEB-exposed TK6 cells is mediated by caspase 9.

Cells were pre-incubated with vehicle alone or 2 μM caspase 9 inhibitor (Z-LEHD-FMK, MBL) for 1 h, followed by exposure to vehicle alone or 10 μM DEB for 24 h. A. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by nuclear morphology fluorescence dye staining. B. Activation of caspase 3 was analyzed by the western blot technique, using 100 μg of extract protein. The 17 K activated form of caspase 3 was detected using a cleaved caspase 3 specific antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). GAPDH levels were determined in order to normalize for the quantity of protein retained on the blot. Relative normalized cleaved caspase 3 levels were obtained after densitometric analysis by normalizing the obtained caspase 3 to GAPDH ratios for each sample to the lowest detectable caspase 3 to GAPDH ratios. Representative western blot data as well as the corresponding graphic representation of the data obtained from three experiments are shown.

3.5. Diepoxybutane-induced apoptosis is mediated through the production of reactive oxygen species in TK6 cells

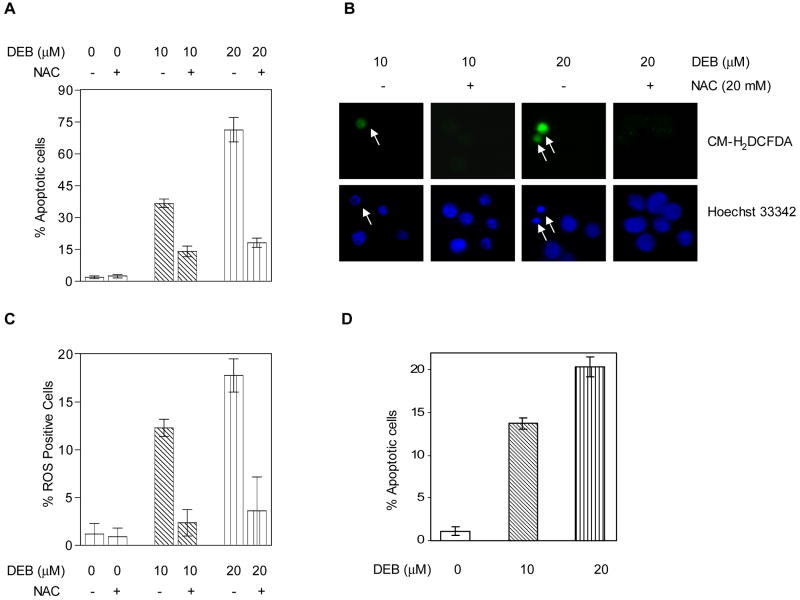

DEB is known to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce oxidative DNA damage in exposed cells (Erexson and Tindall, 2000b), conditions that have been implicated in mediating apoptosis induced by some toxicants (Mohamad et al., 2005). To investigate whether oxidative stress is involved in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis, TK6 cells were pre-treated with the ROS-scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) for 1 h, and cells were then exposed to vehicle, 10 μM, or 20 μM DEB for 24 h. The percentage of apoptotic cells was then determined by fluorescent dye staining and nuclear morphology analysis. As shown in figure 7A, DEB treatment induced apoptosis in a DEB-concentration-dependent manner. In the presence of NAC, however, apoptosis in cells treated with 10 μM and 20 μM DEB for 24 h was effectively decreased by 57% and 75%, respectively. To confirm that ROS were indeed generated and mediated the DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 cells, cells exposed to vehicle, 10 μM, or 20 μM DEB for 12 h in the presence or absence of NAC, were assayed for reactive oxygen species, using the cell permeable ROS indicator CM-H2DCFDA. Figure 7B shows that only cells undergoing apoptosis (determined by Hoechst 33342 staining and marked by arrows) stained positive for ROS, and both ROS production and apoptosis were markedly inhibited by NAC. In fact, the percentage of ROS positive cells increased as the DEB concentration increased, while treatment with NAC reduced the percentage of ROS positive cells by ~84%, regardless of whether cells were exposed to 10 μM or 20 μM DEB (Figure 7C). Interestingly, the percentage of apoptotic cells at 12 h post-DEB exposure (Figure 7D) correlated perfectly to the percentage of ROS positive cells (Figure 7C). These observations are in line with the results of figure 7B, further supporting the observations that at early times in the apoptotic process (12 h), all the cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis are positive for increased ROS. Since prevention of ROS formation effectively blocks DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 cells, the results of figure 7 collectively demonstrate that DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 cells is mediated through the DEB-induced generation of ROS.

Figure 7. DEB-induced apoptosis is mediated through DEB-induced reactive oxygen species.

TK6 cells were exposed to DEB as indicated, in the presence or absence of the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), and apoptosis or ROS were quantitated, as described in Methods. A. Effect of NAC on DEB-induced apoptosis at 24 h post-exposure. B. Representative fluorescence microscopy pictures demonstrating the induction of ROS only in cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis and the effect of NAC on ROS and apoptosis. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain nuclei in order to identify apoptotic cells as well as total number of cells. CM-H2DCFDA (5-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2’,7’-dichlorodihyrofluoroscein diacetate) was utilized as the probe for the detection of ROS-positive cells. C. Effect of NAC on the DEB-induced generation of ROS at 12 h post-exposure to DEB, expressed as a percentage of ROS positive cells. D. The effect of DEB on the percentage of apoptotic cells at 12 h post-DEB exposure.

4. Discussion

Diepoxybutane-induced cell death observed in human lymphoblasts at low concentrations of DEB was recently reported to be due to the occurrence of apoptosis, and not necrosis (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004). In this report, we have demonstrated for the first time that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is activated to mediate DEB-induced apoptosis in human lymphoblasts. This was deduced from the occurrence of several rate limiting hallmarks of this pathway. Up-regulation and activation of Bax and Bak, attenuation of the mitochondrial trans-membrane potential, release of cytochrome c into the cytosol of DEB-exposed Jurkat-T lymphoblasts, and activation of executioner caspase 3 by initiator caspase 9 were observed in cells undergoing apoptosis induced by DEB. In this report, we have also demonstrated for the first time that DEB-induced apoptosis is mediated through the increased generation of ROS initiated by DEB. This is supported by observations that N-acetyl-l-cysteine, a ROS-scavenger, effectively blocked apoptosis initiated by DEB in TK6 cells under conditions where it prevented the DEB-dependent increase in the generation of ROS. This is the first report to examine the mechanism of apoptosis induced by DEB in human lymphoblasts.

A variety of apoptotic stimuli, including DNA damaging agents and oxidative stress, have been reported to stimulate the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by activating, and up-regulating, pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Bax and Bak), thereby provoking dissipation of the mitochondrial trans-membrane potential (Mandic et al., 2001; Jungas et al., 2002; Panaretakis et al., 2002; Chada et al., 2006; Donahue et al., 2006; Kuhar et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Baysan et al., 2007; Jantova et al., 2007). Our observations of Bax and Bak activation and up-regulation, together with attenuation of mitochondrial trans-membrane potential in lymphoblasts undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis, are in line with these reports. Collectively, these observations suggest that the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is activated and involved in mediating apoptosis in our system. This is the first report to examine the involvement of the mitochondrial pathway in DEB-induced apoptosis.

Activation of the mitochondrial pathway by toxicants frequently results in the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol (Gogvadze et al., 2006; Kuhar et al., 2006). Experiments conducted to examine cytochrome c release in lymphoblasts undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis consistently demonstrated a decrease in mitochondrial cytochrome c levels in DEB-exposed TK6 cells. However, release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol was only observed in DEB-exposed Jurkat-T lymphoblastic cells under the same experimental conditions. These observations are in line with the fact that the patterns and kinetics of cytochrome c release in various systems is differentially regulated depending in part on the cell type and the nature of the apoptotic stimulus (Tang et al., 1998; Martinou et al., 2000; Renz et al., 2001; Gogvadze et al., 2006). For instance, U937 lymphoma cells, HL60 leukemic cells, and PC3 epithelial cells treated with staurosporine released cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol, while no cytosolic cytochrome c accumulation was observed in the same cell types upon treatment with BMD188 (a potent apoptotic inducer) (Tang et al., 1998). Likewise, others (Tikhomirov and Carpenter, 2005) reported changes in mitochondrial membrane potential as well as apoptosis, but no significant release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. Thus, it is possible for mitochondrial related apoptosis to occur in the absence of detectable cytochrome c release into the cytosol. In fact, alternative cytochrome c-independent means for activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway initiator caspase 9 have been reported (Bitzer et al., 2002; Costantini et al., 2002; Kim and Park, 2003). The basis for the variation in the patterns of cytochrome c release between the DEB-exposed Jurkat and TK6 cells lines is currently under investigation, and so is the question of how mitochondrial initiator caspase 9 becomes activated in DEB-exposed cells. Nonetheless, the observed DEB-induced changes in the distribution of cytochrome c in TK6 and Jurkat cells, together with the observed activation and translocation of Bax and Bak, and the attenuation of mitochondrial transmembrane potential collectively support a role for the mitochondrial pathway in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis.

In a recent study (Yadavilli and Muganda, 2004), we reported the involvement of caspases 3 and 9 in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 lymphoblasts. In the present study, we confirmed the role of caspase 3 in DEB-induced apoptosis (data not shown). In addition, our results demonstrated a significant reduction in DEB-induced cleavage of caspase 3, as well as DEB-induced apoptosis, in the presence of the caspase 9-inhibitor. Since caspase 9 is the initiator caspase responsible for activating the executioner caspases (such as caspases 3 and 7) within the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (Fan et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Hail et al., 2006), suppression of caspase 3 activation as well as DEB-induced apoptosis by the caspase 9 inhibitor further confirms the involvement of the mitochondrial pathway in DEB-induced apoptosis of human lymphoblasts.

In this report, we have demonstrated for the first time that DEB-induced apoptosis is mediated through the DEB-dependent generation of oxidative stress. The occurrence of DEB-induced oxidative stress and its cytotoxicity effect has previously been reported (Erexson and Tindall, 2000a; Pagano et al., 2003), although its connection to apoptosis has not been previously reported. Oxidative stress, however, has been implicated in mediating apoptosis induced by various toxicants, including cisplatin and dolichyl phosphate (Rybak et al., 2007; Yokoyama et al., 2007). Our results are, thus, in line with these observations. Oxidative stress may be involved in mediating apoptosis at early and/or late stages through different possible mechanisms (Fleury et al., 2002). Oxidative stress may trigger or mediate apoptosis by causing DNA damage, activation of apoptotic signaling pathways (such as MAP kinases and p53), induction of mitochondrial permeability transition, the release of mitochondrial death amplification factors, as well as activation of intracellular caspases (Datta et al., 2000; Kim and Park, 2003; Le Bras et al., 2005). In DEB-exposed TK6 cells, increased ROS were observed as early as 3 h post-exposure. This, and the fact that the observed percentage of ROS-positive was proportional to the DEB exposure concentration, and equal to the percentage of cells undergoing DEB-induced apoptosis, suggests that the DEB-generated oxidative stress may be primarily involved in the early phase of apoptosis (the apoptotic signaling phase). This concept is reinforced by the fact that treatment of DEB-exposed TK6 cells with N-acetyl-l-cysteine prevents the activation of apoptotic signaling pathways (MAP kinases, p53, and others; Martinez-Ceballos and Muganda, to be submitted elsewhere).

In summary, the studies reported here have shown that DEB-induced apoptosis in TK6 lymphoblasts involves activation and up-regulation of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (Bax, Bak), dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential, depletion of mitochondria cytochrome c levels, and activation of initiator caspase 9 to mediate DEB-induced apoptosis, accompanied by activation of executioner caspase 3 by caspase 9. The occurrence of these rate-limiting steps (Martinou et al., 2000; Jin and El-Deiry, 2005; Mohamad et al., 2005) implicates the activation and involvement of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in mediating DEB-induced apoptosis in human lymphoblasts. Our findings also point to the involvement of an oxidative stress-mediated mechanism in the execution of DEB-induced apoptosis in human lymphoblasts. Since the DEB-dependent generation of ROS is an early event proportional to the percentage of DEB-induced apoptosis, and since the activation of DEB-induced apoptotic signaling pathways (MAP kinases and p53) is prevented by the ROS scavenger NAC, then the DEB-dependent oxidative stress is likely to exert its effect on the apoptotic pathway at early times, upstream of mitochondria. Collectively, these findings contribute towards the understanding of DEB-induced apoptosis and toxicity, and therefore of butadiene toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences ARCH Grant ES10018, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences MBRS SCORE Grant GM076530, and in part by National Science Foundation Grant HRD 0450375. We thank Ms. Tillerie Darby for technical support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Statement The authors have no conflicts of interest with any parties that might inappropriately influence the work submitted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam T, Mitschke S, Streibel T, Baker RR, Zimmermann R. Quantitative puff-by-puff-resolved characterization of selected toxic compounds in cigarette mainstream smoke. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:511–520. doi: 10.1021/tx050220w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttinen-Klemetti T, Vaaranrinta R, Mutanen P, Peltonen K. Inhalation exposure to 1,3-butadiene and styrene in styrene-butadiene copolymer production. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2006;209:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysan A, Yel L, Gollapudi S, Su H, Gupta S. Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway by upregulating the expression of Bax and Bim in human B cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitzer M, Armeanu S, Prinz F, Ungerechts G, Wybranietz W, Spiegel M, Bernlohr C, Cecconi F, Gregor M, Neubert WJ, Schulze-Osthoff K, Lauer UM. Caspase-8 and Apaf-1-independent caspase-9 activation in Sendai virus-infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29817–29824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann WG, Kostoryz EL, Eick JD. Correlation of apoptotic potential of simple oxiranes with cytotoxicity. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttke TM, Sandstrom PA. Oxidative stress as a mediator of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1994;15:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chada S, Mhashilkar AM, Liu Y, Nishikawa T, Bocangel D, Zheng M, Vorburger SA, Pataer A, Swisher SG, Ramesh R, Kawase K, Meyn RE, Hunt KK. mda-7 gene transfer sensitizes breast carcinoma cells to chemotherapy, biologic therapies and radiotherapy: correlation with expression of bcl-2 family members. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:490–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini P, Bruey JM, Castedo M, Metivier D, Loeffler M, Susin SA, Ravagnan L, Zamzami N, Garrido C, Kroemer G. Pre-processed caspase-9 contained in mitochondria participates in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:82–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JF, Donovan M, Cotter TG. Regulation and measurement of oxidative stress in apoptosis. J Immunol Methods. 2002;265:49–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta K, Sinha S, Chattopadhyay P. Reactive oxygen species in health and disease. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue SL, Lin Q, Cao S, Ruley HE. Carcinogens induce genome-wide loss of heterozygosity in normal stem cells without persistent chromosomal instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11642–11646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510741103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er E, Oliver L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Manon S, Vallette FM. Mitochondria as the target of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erexson GL, Tindall KR. Reduction of diepoxybutane-induced sister chromatid exchanges by glutathione peroxidase and erythrocytes in transgenic Big Blue mouse and rat fibroblasts. Mutat Res. 2000a;447:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erexson GL, Tindall KR. Micronuclei and gene mutations in transgenic big Blue((R)) mouse and rat fibroblasts after exposure to the epoxide metabolites of 1, 3-butadiene. Mutat Res. 2000b;472:105–117. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(00)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan TJ, Han LH, Cong RS, Liang J. Caspase family proteases and apoptosis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2005;37:719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fas SC, Fritzsching B, Suri-Payer E, Krammer PH. Death receptor signaling and its function in the immune system. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2006;9:1–17. doi: 10.1159/000090767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury C, Mignotte B, Vayssiere JL. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cell death signaling. Biochimie. 2002;84:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Multiple pathways of cytochrome c release from mitochondria in apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RL, Leopold V, McCant D, Honeycutt M. Spatial and temporal trend evaluation of ambient concentrations of 1,3-butadiene and chloroprene in Texas. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;166:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hail N, Jr, Carter BZ, Konopleva M, Andreeff M. Apoptosis effector mechanisms: a requiem performed in different keys. Apoptosis. 2006;11:889–904. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irons RD, Pyatt DW, Stillman WS, Som DB, Claffey DJ, Ruth JA. Comparative toxicity of known and putative metabolites of 1, 3-butadiene in human CD34(+) bone marrow cells. Toxicology. 2000;150:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MA, Stack HF, Rice JM, Waters MD. A review of the genetic and related effects of 1,3-butadiene in rodents and humans. Mutat Res. 2000;463:181–213. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantova S, Cipak L, Letasiova S. Berberine induces apoptosis through a mitochondrial/caspase pathway in human promonocytic U937 cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Overview of cell death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:139–163. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.2.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungas T, Motta I, Duffieux F, Fanen P, Stoven V, Ojcius DM. Glutathione levels and BAX activation during apoptosis due to oxidative stress in cells expressing wild-type and mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27912–27918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy K, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ, Bryant JL, Srivastava RK. Involvement of proapoptotic molecules Bax and Bak in tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced mitochondrial disruption and apoptosis: differential regulation of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO release. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1712–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Park JH. ROS-dependent caspase-9 activation in hypoxic cell death. FEBS Lett. 2003;549:94–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kligerman AD, Hu Y. Some insights into the mode of action of butadiene by examining the genotoxicity of its metabolites. Chem Biol Interact. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar M, Sen S, Singh N. Role of mitochondria in quercetin-enhanced chemotherapeutic response in human non-small cell lung carcinoma H-520 cells. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1297–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras M, Clement MV, Pervaiz S, Brenner C. Reactive oxygen species and the mitochondrial signaling pathway of cell death. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:205–219. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandic A, Viktorsson K, Molin M, Akusjarvi G, Eguchi H, Hayashi SI, Toi M, Hansson J, Linder S, Shoshan MC. Cisplatin induces the proapoptotic conformation of Bak in a deltaMEKK1-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3684–3691. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3684-3691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Desagher S, Antonsson B. Cytochrome c release from mitochondria: all or nothing. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E41–43. doi: 10.1038/35004069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara M, Moll UM. Detection of mitochondrial localization of p53. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;234:203–209. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-408-5:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard JT, Hanly TC, Murphy K, Tretyakova N. The 5’-GNC Site for DNA Interstrand Cross-Linking Is Conserved for Diepoxybutane Stereoisomers. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:16–19. doi: 10.1021/tx050250z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modjtahedi N, Giordanetto F, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Apoptosis-inducing factor: vital and lethal. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad N, Gutierrez A, Nunez M, Cocca C, Martin G, Cricco G, Medina V, Rivera E, Bergoc R. Mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. Biocell. 2005;29:149–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP. 1,3-Butadiene 11th Report on Carcinogens. US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Public Health Service; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano G, Manini P, Bagchi D. Oxidative stress-related mechanisms are associated with xenobiotics exerting excess toxicity to Fanconi anemia cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1699–1703. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretakis T, Pokrovskaja K, Shoshan MC, Grander D. Activation of Bak, Bax, and BH3-only proteins in the apoptotic response to doxorubicin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44317–44326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz A, Berdel WE, Kreuter M, Belka C, Schulze-Osthoff K, Los M. Rapid extracellular release of cytochrome c is specific for apoptosis and marks cell death in vivo. Blood. 2001;98:1542–1548. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak LP, Whitworth CA, Mukherjea D, Ramkumar V. Mechanisms of cisplatin-induced ototoxicity and prevention. Hear Res. 2007;226:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang DG, Li L, Zhu Z, Joshi B. Apoptosis in the absence of cytochrome c accumulation in the cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:380–384. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhomirov O, Carpenter G. Bax activation and translocation to mitochondria mediate EGF-induced programmed cell death. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5681–5690. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. Apoptosis: mechanisms and relevance in cancer. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:627–639. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZB, Liu YQ, Cui YF. Pathways to caspase activation. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadavilli S, Muganda PM. Diepoxybutane induces caspase and p53-mediated apoptosis in human lymphoblasts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama Y, Nohara K, Okubo T, Kano I, Akagawa K, Kano K. Generation of reactive oxygen species is an early event in dolichyl phosphate-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:349–361. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZM, Zhong N, Gao HQ, Zhang SZ, Wei Y, Xin H, Mei X, Hou HS, Lin XY, Shi Q. Inducing apoptosis and upregulation of Bax and Fas ligand expression by allicin in hepatocellular carcinoma in Balb/c nude mice. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006;119:422–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]