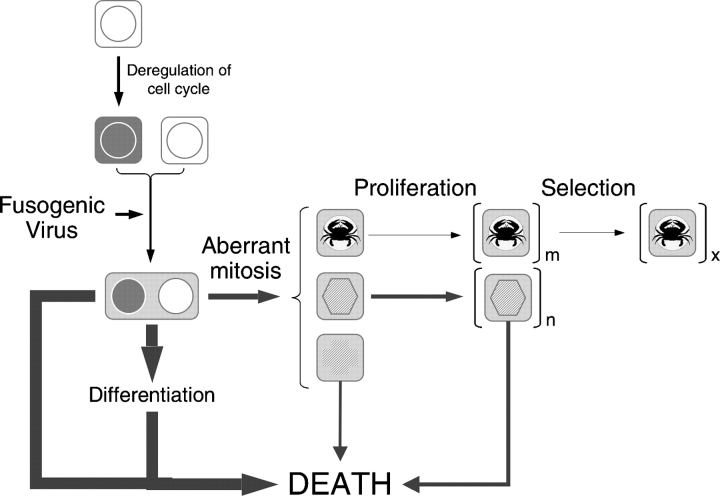

Figure 9.

Cell fusion as a link between viruses and carcinogenesis. Potential implications of our findings to carcinogenesis could be summarized by the following speculative model. Although illicit cell fusion induced by viruses may be a frequent and common event, it usually has no consequences for carcinogenesis because, as a rule, the resulting cells either die or do not proliferate. However, if the cells have a deregulated cell cycle and if the virus tends to produce dikaryons rather than syncytia, the fused cells may proliferate. The majority of these cells, however, die within a few cell divisions because of chromosomal aberrations associated with abnormal mitoses or other, yet unrecognized, consequences of cell fusion. However, the few cells that survive are abnormal in that they have a deregulated cell cycle, lack normal response to this deregulation, are aneuploid, and have epigenetic regulation that is an unpredictable result of the merger between fusion partners. A combination of these properties in a minute fraction of the fused cells may be sufficient to make them cancerous. Considering that a single cell can give rise to a cancer, the frequency with which cell fusion produces such cells does not need to be high to have pathological consequences.