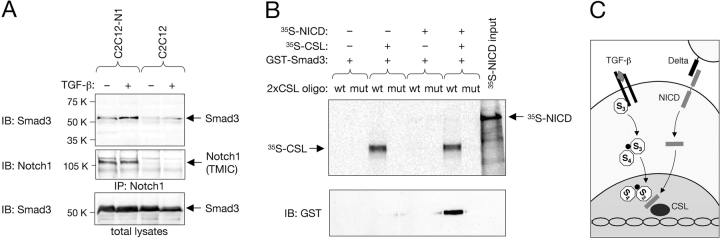

Figure 5.

Ligand-dependent interaction between endogenous Smad3 and Notch, and recruitment of Smad3 to specific DNA sites by CSL and NICD. (A) Parental C2C12 cells or a stable C2C12 transfectant overexpressing full-length Notch1 (C2C12-N1) were either left untreated or stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 50 min before lysis and immunoprecipitation with anti-Notch1 antibodies. Immunoblots were probed with anti-Smad3 antibodies and reprobed with anti-Notch1, detected as its transmembrane and intracellular (TMIC) domain. It should be noted that to date, nuclear NICD has been very difficult to detect by biochemical or in situ methods in normal cells, possibly because it is present in very low amounts and/or has a very short half-life (Rand et al., 2000). (B) A biotinylated oligonucleotide containing two tandem CSL-binding sites (2xCSL) was used to pull down GST–Smad3, 35S-labeled NICD, and 35S-labeled CSL in different combinations as indicated. A mutant oligonucleotide (mut) was used as a control. Note that GST–Smad3 (detected by immunoblot with anti-GST antibodies) could only be recovered using the wild-type (wt) oligonucleotide in the presence of both NICD and CSL. Weak levels of 35S-labeled NICD could also be detected in the same lane. (C) A mechanism for the integration of TGF-β and Notch signaling by direct interaction between Smad3 and NICD. Although the Smad3–Smad4 complex and the NICD can translocate to the nucleus independently, our results do not rule out the possibility that their interaction could already take place in the cytoplasm.