Abstract

Background

As patients grow older, accurate communication with health care providers about cancer becomes increasingly important. However, little is known about the cancer communication experiences of older Asian immigrants.

Objective

To learn about the cancer-related communication experiences of older Vietnamese immigrants from the insider perspective.

Design

Qualitative study (grounded theory, constant comparative method) using individual interviews with older Vietnamese immigrants with the purpose of discussing how they learn about cancer. Interviews were conducted in Vietnamese.

Participants

Vietnamese immigrants aged 50–70 years, recruited through community-based organizations. Most had low education and limited English proficiency. The sample size of 20 was sufficient to achieve theoretical saturation.

Results

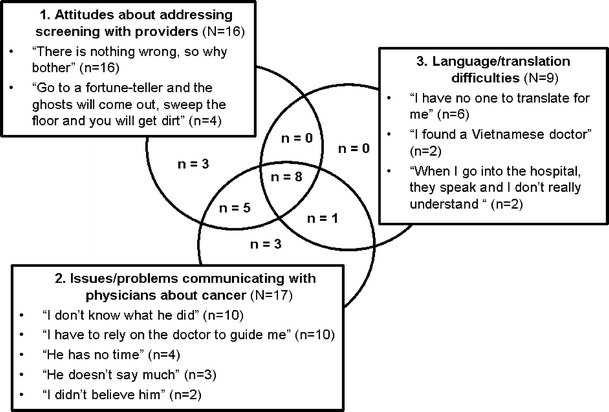

We identified 3 categories of themes concerning informants’ experiences with cancer communication in the health care setting: (1) attitudes about addressing screening with providers, (2) issues/problems communicating with physicians about cancer, and (3) language/translation difficulties. There was substantial overlap between informants who mentioned each theme category, and 40% of the participants mentioned all 3 categories.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of and act upon specific cancer communication needs/challenges of their older immigrant patients. Moreover, health care systems need to be prepared to address the needs of an increasingly multiethnic and linguistically diverse patient population. Finally, community-level interventions should address baseline knowledge deficits while encouraging immigrant patients to engage their doctors in discussions about cancer screening.

KEY WORDS: communication, cancer, immigrant, Asian, doctor–patient relationship

INTRODUCTION

As American society becomes increasingly multicultural and linguistically diverse, and as primary care providers continue to see larger numbers of older adult immigrants and refugees, the health information needs of these diverse populations must be acknowledged and addressed. These needs become increasingly apparent in the setting of limited English proficiency, low education, and low health literacy.1

There are nearly 1.3 million Vietnamese Americans in the United States, and over 70% are foreign-born. This is a disadvantaged group, with 14% in poverty and 30% of adults having under high school education (compared to 8.8% and 11.4% in non-Hispanic Whites); poverty rates for Vietnamese immigrants age 65+ are even worse, 16.6%. Meanwhile, nearly 90% of Vietnamese Americans speak a language other than English at home, and 55% speak English less than “very well”.2 Vietnamese Americans also suffer from cancer-related disparities, including disproportionately high mortality from lung, cervical, and liver cancer and low screening rates for cervical, prostate, and colon cancer.3

Primary care physicians play a key role in communicating with patients about cancer and would benefit from a clearer contextualization of immigrant experiences with the communication process. As such, it is important to allow members of these communities to speak directly of their own experience rather than to approach them with the preconceived views of scientists and clinicians. An emic approach whereby concepts arise from within the community’s “insider” perspective can yield a richer understanding than the usual etic, or external, investigator-driven approach.4

We define cancer communication broadly as any exchange of information about cancer between a health care consumer and an information source, including electronic, print, and interpersonal sources. Such information exchange can occur within the context of active information seeking, or through more passive exposure (i.e., “scanning”).5

Little is known about the cancer communication experiences of Vietnamese Americans. The Health Information National Trends Survey was the first national study designed specifically to address cancer communication, and yet few Asians were represented in the sample.6 Another study, which included Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Cambodian Americans, examined awareness of clinical trials and NCI’s 1-800-4-CANCER service, but it did not address doctor–patient communication about cancer beyond asking if smokers had been advised to quit.7 Also, a study of adult Vietnamese men in Seattle reported that 58% had received some form of health information from doctors/nurses, but it did not focus on women, older adults, or cancer.8

The purpose of this study is to examine elements of provider–patient cancer communication from the viewpoint of older Vietnamese immigrants. By understanding these key elements, we hope to identify areas on which to focus limited resources to maximize cancer control efforts and improve patient care. Although this study is focused specifically on Vietnamese immigrants, it brings to light issues of relevance to other Asian American and immigrant populations.

METHODS

We recruited 20 Vietnamese immigrants, aged 50–70 years, with no personal history of cancer. The age restriction reflects ages most likely to engage in screening decisions such as colonoscopy, mammography, and PSA testing.9–11 Participants were recruited through community-based organizations serving Vietnamese populations in Philadelphia. We used purposive sampling to recruit equal numbers of male and female immigrants who were age-appropriate for doctor–patient discussions about cancer screening. Participants were given $20 as a token of appreciation. Informant identities were not recorded in the study data.

We conducted semistructured, one-on-one interviews in locations selected by participants (usually at home). All sessions were conducted in Vietnamese by bilingual, bicultural research staff, using an interview guide focusing on cancer in general and colon, breast (women only), and prostate (men only). These cancers represent diseases for which information seeking could be of greatest benefit, given the complexity of potential decisions (e.g., controversy about age to begin mammography, uncertain utility of PSA, and multiple options for colon screening). Questions were created to elicit comments about cancer prevention/screening, cancer information seeking, and related personal experiences. Whereas each interview was different, they all followed the same basic structure; sample questions are listed in Table 1. A related study using similar questions among a general adult population (mostly White and African American) has been described elsewhere.5 The interview guide yielded responses about a wide range of issues (e.g., cancer information from mass media), but the present report focuses only on the 986 lines of transcript text relevant to cancer communication in the health care setting (∼10% of the total text available). The interview format was pilot-tested and refined before implementation. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and translated into English for coding. Bilingual reviewers compared translated transcripts to the audio recordings to ensure accuracy of translation.

Table 1.

Sample Interview Questions

| Questions |

|---|

| General cancer beliefs |

| What comes to mind when you think about health? |

| What comes to mind when you think about cancer? |

| Where did you hear that? |

| Prevention |

| What can people do to avoid cancer? What can people do to avoid breast/prostate/colon cancer? |

| Where did you hear or see this information? |

| Have you ever actively looked for information about this? |

| Screening |

| What do you know about mammogram/PSA/colon cancer screening? |

| Where did you hear or see this information? |

| Have you ever actively looked for information about this? |

| For each area of inquiry, interviewers asked specifically about the following potential sources of information if not spontaneously offered by the informants |

| Public sources: television, internet, radio, newspaper, magazines, books, pamphlets |

| Interpersonal sources: doctor/health care provider, friends/family |

| Personal experiences |

| How did the information (about cancer) affect you? Did you do anything differently? |

| Have you had mammogram/PSA/colonoscopy? |

| Within the last 10 years, has any immediate family member been diagnosed with cancer? What type of cancer? Do you remember looking for any information on their behalf? Tell me about how you came across that information. |

We examined the text using grounded theory4 and managed the textual data using QSR N6 qualitative analysis software.12 The study team reviewed all transcripts and allowed key ideas (themes) to emerge from the data. Codes were applied to lines of text pertaining to these themes so that we could compare similar ideas across cases.13 Once a parsimonious set of themes was identified and no new ideas emerged, we determined that we had reached saturation and terminated data collection. Results in this paper will be reported through representative quotes, and theme category frequency will be depicted diagrammatically.

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We completed 20 interviews, which were sufficient to achieve theoretical saturation (i.e., later interviews did not reveal new themes not already mentioned in earlier interviews).14 A description of the sample is provided in Table 2. Not all participants had limited English proficiency, but all expressed a preference for speaking in Vietnamese over English.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics

| Sample Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, median years | 64.5 |

| Immigration age, median years | 49.5 |

| Immigration year, median | 1992 |

| Education in Vietnam | |

| Less than High School graduate | 70% |

| High School graduate | 15% |

| Some college or more | 15% |

| Education in USA | |

| None | 60% |

| Vocational or trade school | 15% |

| Some college | 5% |

| ESL | 20% |

| English-speaking ability, self-reported | |

| Very well | 10% |

| Well | 20% |

| Not well | 35% |

| Not at all | 35% |

| Access to regular source of health care | |

| Vietnamese primary doctor* | 70% |

| Non-Vietnamese primary doctor | 25% |

| No regular doctor | 5% |

*All patients in this category spoke Vietnamese with their doctors

Less than two-thirds of participants (60%) reported having heard of a way to detect colon cancer involving a tube used by doctors to look at the colon. Most of the women (90%) had heard of an x-ray test to detect breast cancer, but only 20% of men had heard of a blood test to detect prostate cancer. Indeed, most men in our study had little to say about prostate cancer and reported little communication with health care providers about it.

Respondents frequently expressed confusion about anatomy and other basic medical matters. For example, men often were unclear about what the prostate was (with some men thinking that it might be near the lung or in the neck). Respondents also did not seem to recognize the differences among cancers originating in different organs. For instance, one of the more highly educated participants incorrectly believed that the new anticancer vaccine protected women against breast cancer rather than cervical cancer.

We identified 3 broad categories of themes related to how participants interacted with the health care system in the context of cancer communication: (1) attitudes about addressing screening with providers, (2) issues/problems communicating with physicians about cancer, and (3) language/translation difficulties. Figure 1 describes these themes graphically, indicating the overlap among themes described by informants.

Figure 1.

Main themes discussed by informants. Most informants discussed multiple themes, as indicated by the Venn diagram.

Theme Category 1 Attitudes about addressing screening with providersInformants’ comments fell into 2 themes when discussing why individuals lacked motivation to address cancer screening during interactions with health care providers:“There is nothing wrong, so why bother” (n = 16 people mentioned this theme)—The idea that cancer is only a concern when symptoms arise was mentioned by equal numbers of men and women. They spoke of a willingness to address medical conditions they already knew they had (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) but felt that, in the absence of symptoms, cancer was not relevant. Speaking of colon cancer, 1 woman said:

I know an acquaintance who had died of [colon] cancer... He had what they called hemorrhoids or something for decades. When he came to the US and went for a checkup, they said that he had colon cancer. Within the next 2 or 3 years later, he died! ...If there are any symptoms or something, like bleeding, constipation, or something then you should go get examined one time... this cancer can’t occur without no reasons...It happens to those who have blood in stool... My stool is normal. There is no blood in it. I do not have constipation. I have a peace of mind that I don’t have colon cancer.

Even in the case of participants who had received recommended screening once in the past, the prevailing belief that the absence of symptoms equates to absence of disease persisted. An exception may be the case of mammography, in which women often spoke of being tested regularly, even when results were normal.“Go to a fortune-teller and the ghosts will come out, sweep the floor and you will get dirt [Xem bói ra ma, quét nhà ra rác]” (n = 4)—This Vietnamese proverb expresses a belief that one should not look for problems unless there is a strong reason for it; otherwise, one invites new troubles into one’s life: “[Only] sweep the house when it is dirty, and invite the [fortune-teller] if there [truly is] a ghost in your house. If there is nothing wrong, no need to go to visit doctor”. Another informant said it this way:

Going to the doctor is looking for trouble. You waste your time, going back and forth... Then if they discover something, you become worried and sad. That is the thinking of the Vietnamese people... This even I myself have said, “If I am ill, then I’ll go (to the doctor), if I’m not, I just don’t want to go.” Honestly it’s like that.

All of the people who mentioned this theme also ascribed to the “there is nothing wrong, so why bother” theme. The main difference, however, is that this theme suggests potential harm from screening, whereas the earlier theme merely focused on its lack of utility.

Theme Category 2 Issues/problems communicating with physicians about cancerRespondents generally trusted information from doctors. At the same time, however, they did not frequently engage doctors in discussions about cancer. They offered several descriptions of their cancer communication experiences with doctors:“I don’t know what he did (n = 10)”—Patients often expressed poor understanding of medical tests that they had received. For instance, 1 man described his experience with endoscopy several months previously. Rather than for screening, he had this test in response to abdominal pain. However, after the test was done, he still did not know whether it was a colonoscopy or an upper endoscopy.“I have to rely on the doctor to guide me” (n = 10)—Other respondents spoke more at length about how they depended on doctors to tell them what they needed to know, and to advise them on any necessary tests or treatments. Seeing this as the full responsibility of the doctor, these patients felt that it was not their role to seek information on their own. Overall, there was an acceptance of the paternalistic doctor–patient relationship, and a reliance on the health care system to tell patients what to do and when to do it. When providers failed to recommend age-appropriate screening, however, important preventive health measures were overlooked. For example, 1 woman received regular mammography because of her doctor’s recommendation, but reported that she had never been advised to screen for colon cancer.Reminders or other literature from the doctor or hospital played an important role for some, particularly in the context of mammograms. One woman spoke of how she relied on her children, who could read English, to notice when the doctor’s reminder appeared in the mail and to take her to the hospital for testing. She was content to have her health matters overseen by her doctor, her children, and the government: “I think it’s great. The doctors are willing to check for us. The government provides us health care. Why shouldn’t we get a checkup? If we are not lucky and we have to die then we die. We should not complain because there is someone to remind us and [who is] concerned for us”.“He has no time” (n = 4)—Participants also stated that time constraints caused a disinclination to engage their doctors in discussions about cancer. One woman recalled having difficulty interpreting the bits of information about cancer prevention she had received from friends; however, she never discussed her confusion with her doctor because she did not want to take time from his many other patients. Meanwhile, another woman’s attempt to engage her doctor in a discussion about cancer was met with outright resistance: “[If] I ask her, she just yells at me, [so] I don’t ask. She says, ‘I’m letting you go [for your test] already, so go do it. Why do you ask?’”“He doesn’t say much” (n = 3)—Several participants noted that doctors said little in general and tended not to speak about cancer specifically. Doctors, they said, addressed only the chief complaints and spoke of little else. One woman also voiced the belief that doctors might hide a cancer diagnosis from a patient: “The situation in Vietnam is that [doctors] often hide this because of fear that the patient will worry too much.”“I didn’t believe him” (n = 2)—A minority spoke of distrust of the doctor’s advice. One woman noted that if a doctor was not an expert in the medical issue at hand, he might not be able to offer sufficient guidance; in such a case, a referral was expected. In addition, if the doctor’s rationale did not appear logical, trust would be lost. For example, 1 man said that a cardiologist had tried to convince him to get a catheterization because his heart was “leaky.” However, the patient and his family refused the procedure, feeling that if his heart were leaking, he would have died already.

Theme Category 3 Language/translation difficultiesEqual numbers of men and women spoke of linguistic difficulties when interfacing with doctors and the health care system.“I found a Vietnamese doctor” (n = 2)—Informants voiced that they felt most reassured going to doctors with whom they shared the same ethno-linguistic background. Said 1 woman, “I don’t know English. Seeing Vietnamese doctor allows me to explain the illness I have in my body so that the doctor can prescribe the right medicine. Otherwise, I would be like a mute and would not understand anything...” However, Vietnamese doctors were not always accessible to patients, and patients sometimes had to communicate with doctors in English, despite a preference for Vietnamese.“When I go into the hospital, they speak and I don’t really understand” (n = 2)—Even when patients had Vietnamese primary care doctors, they faced challenges when going to the hospital or to specialists. For example, 1 woman described her experience at the breast imaging center as follows:

[The technicians] only say “good” [in English]. Those white women keep saying, “good, good,” and it’s just like that, other than that I don’t know anything else... I only hear the sound, “GOOD, GOOD,” the sound of them congratulating me... Hearing that makes me happy and that is all, they don’t say how I am...

“I have no one to translate for me” (n = 6)—Informants also spoke at length about the lack of language assistance. They were reluctant to impose upon their children to take time from work to accompany them to doctor’s appointments and to serve as interpreters. For those without anyone to translate for them, it was even more difficult. At times, this led to delays in follow-up care. One woman said:

So now they tell me every year I must go once [for testing]... But when I go there isn’t anyone to translate for me. The other day they mailed me a letter. There wasn’t anyone to translate for me, so I just ignored it again.... After I find a person to translate I will go...

One man even went so far as to ask strangers in the doctor’s waiting room to serve as his interpreters:

There is [a translator in the doctor’s office] but they... are Chinese, they know very little Vietnamese... I only ask [other] people to help. I don’t bring anyone. I have no one to bring along. [So I ask the people in the waiting room] who go to see the doctor. [If] they know English, then they will talk for me.

None of our informants voiced the understanding that health systems are required to provide translation/interpretation services for patients like them.

DISCUSSION

Doctor–patient interaction, language access, and patients’ own attitudes about screening are highly salient to older Vietnamese immigrants when describing their experiences with cancer communication in the health care setting. Patients in this study seemed unsatisfied with doctor–patient communication about cancer, even when doctors shared the patients’ ethno-linguistic background. Screening discussions are not always taking place because patients and providers are not bringing up the topic. These issues are further complicated by language difficulties.

The National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care (CLAS) provide a framework for addressing language access in the medical setting.15 However, our study suggests that currently available services may be lacking in quality control, and patients are unaware of the CLAS mandates. Moreover, interpreters in the exam room alone cannot prevent miscommunication during outpatient testing or when arranging referrals and follow-up. Indeed, 70% of the informants discussing “issues/problems communicating with doctors” actually had Vietnamese doctors with whom they spoke the same language.

Unlike other minority communities (e.g., African Americans), our sample did not reveal much evidence for lack of trust in doctors.16 In fact, our participants generally voiced a strong sense of dependence upon their physicians and respected what little advice they received from them. This points to a more external locus of control, which was clearly directed at the doctor. Trust issues in our data revolved around perceived physician expertise rather than concerns over discrimination. Physicians’ explanations about why screening tests are important must therefore come across as logical within patients’ worldviews and should take into account their baseline level of knowledge. Also, it is important for clinicians to identify instances where patient perceptions of how the body works and how cancer occurs may be different from professional interpretations; misconceptions should be viewed not as being “wrong” (even if they are), but as opportunities to reconcile different explanatory models between doctor and patient and to strengthen the therapeutic relationship.

Time constraints often prevent primary care physicians from accomplishing all recommended preventive tasks.17 Consequently, screening is more likely to be discussed if patients initiate the conversation.18 Older immigrants, however, may not feel empowered to do this, especially when doctors discourage questions.

It is striking that many patients in our study did report having had screening despite the prevalent belief in “there is nothing wrong, so why bother.” It appears that physician recommendation may have superseded this belief, underscoring the importance that physicians take every possible opportunity to encourage screening in this population (e.g., acute visits for unrelated symptoms).

The generally high regard for physician advice was consistent with prior work in Asian Americans, but our study goes beyond discussing the core values described elsewhere for Asian immigrants (i.e., collectivism, conformity, emotional self-control, family recognition through achievement, humility, and filial piety).19,20 For example, some of our findings about beliefs underlying the reluctance to screen are new, as are the specific relationships we identified between provider–patient interaction and cancer communication. The remarks from our study participants also provide new context for interpreting the mental health and stroke literature suggesting that Asians tend to delay seeking medical care.21,22 Countervailing influences on preventive behavior (i.e., paternalistic faith in physician recommendations and personal reluctance to address cancer screening) should be examined more closely.

Interestingly, the informants in this study did not bring up concerns about cultural differences between them and their doctors. This may be because of the fact that many of them had Vietnamese doctors. Moreover, the language access issues for patients with non-Vietnamese doctors perhaps were so overwhelming that they may not have recognized more subtle cultural discordance.

Also interesting is our finding that many participants subscribed to more than 1 of the thematic categories we identified. In fact, 40% of our sample discussed all 3 of the categories, suggesting the importance of all of these concepts in the minds of older Vietnamese immigrants.

As this study was limited to Vietnamese immigrants, it is difficult to generalize our findings to other racial/ethnic groups. Ultimately, similar studies with other ethnic groups will allow meaningful comparisons; however, we expect that many of the ideas put forth by our informants would be echoed by other Asian immigrants. Selection bias is a potential limitation. However, as it is difficult to obtain a truly random sample of Vietnamese immigrants (particularly among those who are most culturally and linguistically isolated), it is reasonable and feasible to use community groups that serve this population to facilitate recruitment. This type of study recruitment has been used successfully by other investigators in the area of Asian American health.23 However, our quantitative findings should be interpreted with caution (e.g., one must not assume that 85% of Vietnamese immigrants have doctor–patient communication issues simply because 17 of 20 informants discussed this in our study).

Transcription issues offered unique challenges in this study. However, we used a professional research support service specializing in foreign languages including Vietnamese; in addition, all translations were confirmed by bilingual research staff. The question of anonymity is an important one, particularly when informants are asked about personal experiences and behaviors. However, participants’ names were not linked with the study responses, and this was made clear at the beginning of the interview. Also, as participants were recruited through community groups, there was an added level of trust.

Future research could focus on ways to bridge the apparent disconnect between physician and immigrant patient perspectives on cancer and preventive health care. Further efforts to disentangle the overlapping influences of education, socioeconomic status, culture, and language would also aid in the creation of appropriate interventions. Cancer communication programs should include efforts in both clinical and community settings.

Community-level interventions should include public health campaigns crafted specifically to fill in the gaps by educating immigrant communities about information that American physicians are likely to assume that all patients know (e.g., basic anatomy, navigation of the American health care system). In addition, preventive behaviors and engagement of physicians should be encouraged in a way that is consistent with immigrants’ underlying cultural constructs.

Meanwhile, providers must also be vigilant for cues that patients do not fully comprehend them, or that patients desire additional information. In addition, policymakers may need to create positive incentives for all health care providers, including ethnic minority physicians, to improve the process of information exchange between patients and their providers, medical support staff, and health care systems, particularly in the context of cancer.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported in part by Grant Number 5P50CA095856-04 from National Cancer Institute. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI. Additional funding was provided by pilot grants from the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (University of Pennsylvania) and the Center for Asian Health (Dr. Grace X. Ma, Temple University). Dr. Nguyen was supported by a Cancer Control Career Development Award from the American Cancer Society (CCCDA-05-161-01) and a Pfizer Fellowship in Health Literacy/Clear Health Communication. The authors wish to thank the Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition, the Vietnamese United National Association of Greater Philadelphia, the Vietnamese Association for Aging in Philadelphia and Suburbs, and the Vietnamese community of Saint Helena Church for their assistance in participant recruitment. They also wish to thank Chau Nguyen, To Lan Chau, Dr. Huan M. Vu, and Gia An Vu for data collection/data management and Dr. Marjorie Bowman (University of Pennsylvania) for her thoughtful review of prior versions of this paper. Finally, they thank the anonymous reviewers of this journal, whose constructive suggestions helped to shape the final paper.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Nguyen GT, Bowman MA. Culture, language, and health literacy: communicating about health with Asians and Pacific Islanders. Fam Med. 2007;39(3):208–10. [PubMed]

- 2.US Census Bureau. The American Community—Asians: 2004. 2007 Feb. Report No.: US Census ACS-05.

- 3.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr., et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):190–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Weiss MG. Cultural epidemiology: an introduction and overview. Anthropol Med. 2001;8(1):5–28. [DOI]

- 5.Niederdeppe JD, Hornik RC, Kelly BJ, et al. Exploring the dimensions of cancer-related information seeking and scanning behavior. Health Commun. 2007;22(2):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Nguyen GT, Bellamy SL. Cancer information seeking preferences and experiences: disparities between Asian Americans and Whites in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Commun. 2006;11(Suppl 1):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ma GX, Fleisher L. Awareness of cancer information among Asian Americans. J Commun Health. 2003;28(2):115–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Woodall ED, Taylor VM, Yasui Y, et al. Sources of health information among Vietnamese American men. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):263–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. 2002. Report No.: 03-510A.

- 10.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). Screening for Breast Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. 2002. Report No.: 03-507A.

- 11.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsprca.htm. 2002:Accessed May 10, 2007.

- 12.Richards L. Using N6 in Qualitative Research Doncaster Victoria Australia: QSR International; 2002.

- 13.Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002;36(4):391–409. [DOI]

- 14.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry, ch 2. . In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:33–45.

- 15.Office of Minority Health. (US Department of Health and Human Services). National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care: Final Report. 2001 Mar.

- 16.Blocker DE, Romocki LS, Thomas KB, et al. Knowledge, beliefs and barriers associated with prostate cancer prevention and screening behaviors among African-American men. J Nat Med Assoc. 2006;98(8):1286–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Fairfield KM, Chen WY, Colditz GA, Emmons KM, Fletcher SW. Colon cancer risk counseling by health-care providers: perceived barriers and response to an internet-based cancer risk appraisal instrument. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(2):95–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Guerra CE, Jacobs SE, Holmes JH, Shea JA. Are physicians discussing prostate cancer screening with their patients and why or why not? A pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kim BSK, Li LC, Ng GF. The Asian American values scale—multidimensional: development, reliability, and validity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psycholology. 2005;11(3):187–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Li FP, Phillips RS. Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. Am J Med. 2003;115(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kramer EJ, Kwong K, Lee E, Chung H. Cultural factors influencing the mental health of Asian Americans. West J Med. 2002;176(4):227–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Smith MA, Doliszny KM, Shahar E, McGovern PG, Arnett DK, Luepker RV. Delayed hospital arrival for acute stroke: the Minnesota Stroke Survey.[see comment]. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(3):190–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ma GX, Shive S, Tan Y, Toubbeh J. Prevalence and predictors of tobacco use among Asian Americans in the Delaware Valley region. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):1013–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]