Abstract

Theory shows that speciation in the presence of gene flow occurs only under narrow conditions. One of the most favourable scenarios for speciation with gene flow is established when a single trait is both under disruptive natural selection and used to cue assortative mating. Here, we demonstrate the potential for a single trait, colour pattern, to drive incipient speciation in the genus Hypoplectrus (Serranidae), coral reef fishes known for their striking colour polymorphism. We provide data demonstrating that sympatric Hypoplectrus colour morphs mate assortatively and are genetically distinct. Furthermore, we identify ecological conditions conducive to disruptive selection on colour pattern by presenting behavioural evidence of aggressive mimicry, whereby predatory Hypoplectrus colour morphs mimic the colour patterns of non-predatory reef fish species to increase their success approaching and attacking prey. We propose that colour-based assortative mating, combined with disruptive selection on colour pattern, is driving speciation in Hypoplectrus coral reef fishes.

Keywords: speciation, coral reef fishes, colour pattern, population genetics, assortative mating, aggressive mimicry

1. Introduction

The colours displayed by coral reef fishes are among the most visually stunning phenotypic traits in animals. Coral reef fish colour patterns have been claimed to serve such diverse functions as crypsis (Cott 1940), mimicry (Randall & Randall 1960) or poster coloration to conspicuously identify conspecifics (Lorenz 1966), but the role played by colour pattern in the process of coral reef fish speciation remains poorly understood (McMillan et al. 1999).

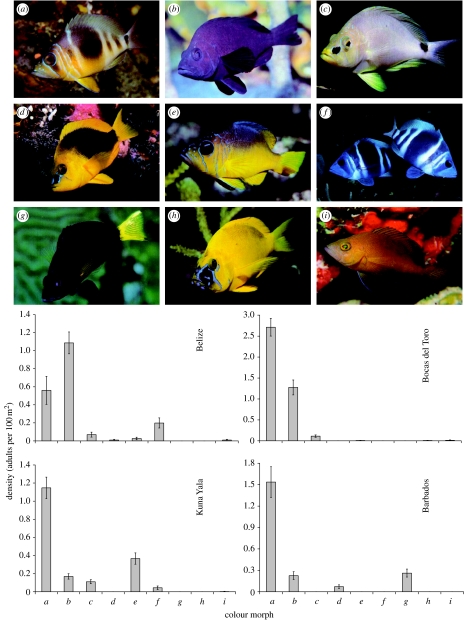

Caribbean coral reef fishes in the genus Hypoplectrus present an unparalleled opportunity to investigate colour polymorphism and its role in marine speciation. These fish, commonly called hamlets, include at least 11 distinct colour morphs (figure 1), with as many as seven morphs recorded from the same reef (Fischer 1980a). Colour pattern is genetically determined (Domeier 1994) and hamlets have been shown to pair assortatively by colour pattern (Fischer 1980a). Nonetheless, spawning events between different colour morphs as well as individuals with intermediate colour patterns have been observed in the wild (present study; Fischer 1980a; Domeier 1994), suggesting the potential for gene flow between colour morphs. There are no intrinsic post-zygotic barriers between colour morphs (Domeier 1994) and to date no ecological, behavioural or morphological trait other than colour pattern has been shown to clearly distinguish the different hamlet morphs (Randall 1983; Böhlke & Chaplin 1993). Population genetic analyses have failed to reveal consistent differences between Hypoplectrus colour morphs (Graves & Rosenblatt 1980; McCartney et al. 2003; Ramon et al. 2003; Garcia-Machado et al. 2004), and although most colour morphs have been described as species (e.g. Poey 1852; Acero & Garzón-Ferreira 1994), a century of study and debate has not settled the question of whether hamlets are distinct species or a single species displaying ‘endless variations in colour’ (Jordan & Evermann 1896).

Figure 1.

Nine Hypoplectrus colour morphs and densities (number of adults per 100 m2, mean±s.e.) in Belize, Bocas del Toro (Panama), Kuna Yala (Panama) and Barbados as assessed from 29, 40, 90 and 21 transects, respectively, covering a total of 72 000 m2 of reef. (a), H. puella; (b), H. nigricans; (c), H. unicolor; (d), H. guttavarius; (e), H. aberrans; (f), H. indigo; (g), H. chlorurus; (h), H. gummigutta; (i), tan hamlet. Photographs with permission from Reef Fish Identification, New World Publications, © 2002, Paul Humann.

Randall & Randall (1960), followed by Thresher (1978), suggested that hamlet colour morphs might have evolved as aggressive mimics. According to this hypothesis, predatory hamlets that mimic the colour pattern of non-predatory coral reef fish models have a fitness advantage resulting from increased success approaching and attacking their prey. Seven putative mimic–model pairs have been identified (Randall & Randall 1960; Thresher 1978), but behavioural evidence of aggressive mimicry in hamlets is lacking.

Disruptive natural selection on the colour pattern of hamlets to match coral reef fish models provides one possible mechanism for the origin of colour differences among some Hypoplectrus colour morphs, and in association with the assortative pairing by colour observed by Fischer (1980a), may provide an explanation for both the origin and maintenance of colour variation in this group of reef fish. Maynard Smith (1966) pointed out that the combination of assortative mating and disruptive natural selection on a single trait, sometimes referred to as a ‘magic trait’ (Gavrilets 2004), establishes one of the most favourable scenarios for speciation in the presence of gene flow (see also Moore 1981; Slatkin 1982; Dieckmann & Doebeli 1999; Kirkpatrick 2000; Gavrilets 2004; Schneider & Bürger 2006). We provide the following three lines of evidence demonstrating the potential for colour pattern to drive speciation in the genus Hypoplectrus: (i) significant genetic differences between sympatric barred (Hypoplectrus puella), black (Hypoplectrus nigricans) and butter (Hypoplectrus unicolor) hamlets in Belize, Panama and Barbados, (ii) behavioural observations of colour-associated assortative mating in Belize, Panama and Barbados, and (iii) behavioural evidence of aggressive mimicry of H. unicolor in association with its putative model, the foureye butterflyfish (Chaetodon capistratus) in Panama.

2. Material and methods

(a) Sampling

In order to investigate the relationship between assortative pairing and genetic differentiation between hamlet colour morphs, we collected large population samples of barred (H. puella), black (H. nigricans) and butter (H. unicolor) hamlets from Belize, Panama and Barbados. These morphs are ubiquitous throughout the Caribbean, thus permitting comparative analysis at a regional scale (figure 1).

Collecting, export and import permits were obtained prior to fieldwork. Sampling was undertaken in the vicinity of Carrie Bow Cay (Belize) in 2004, in Bocas del Toro (Panama) in 2004 and 2005, and along the west coast of Barbados in 2005. Hamlets were collected with microspears, while SCUBA diving over coral reefs at depths between 8 and 100 feet. Behavioural observations and fish collected for genetic analyses were carried out sequentially on the same reefs. Fish were killed in order to use specimens for an array of analyses, including meristic counts and stomach content analysis. The microspear method was efficient and highly selective, causing no damage to the reef or other fish species. The majority of the fish sampled were photographed underwater before and/or immediately after collection and all were preserved on ice until identified, labelled and photographed in the laboratory within a few hours after collecting. Gill tissue samples for genetic analyses were preserved in salt-saturated DMSO buffer. Entire fish were preserved in 10% formalin until accessioned and stored in 70–75% ethanol as voucher specimens in the Neotropical Fish Collection (Bermingham et al. 1997) at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. Specimens, photographs, and DNA samples of all fish considered in this study are available upon request.

(b) Genetic analyses

An enriched Hypoplectrus microsatellite library was constructed and five microsatellite markers were developed (electronic supplementary material). We used these markers as well as five previously developed loci (McCartney et al. 2003) to analyse a total of 371 Hypoplectrus samples, with an average sample size of 46 individuals per colour morph per location (electronic supplementary material). Fst between sympatric colour morphs were estimated following Weir & Cockerham (1984) and genetic differentiation was tested with 10 000 allele permutations using the G log-likelihood statistic (Goudet et al. 1996).

(c) Hamlet densities and spawning observations

Hamlet densities were assessed during the day on the same reefs where spawning observations were made later in the early evening. Two SCUBA divers surveyed non-overlapping 100×4 m transects between 8 and 80 feet, with each diver counting all hamlets observed 2 m on each side of a 100 m transect tape.

Spawning observations were performed using SCUBA in water 10–60 feet deep, during a period beginning roughly 1 h before sunset and ending roughly 15–30 min after sunset. Only hamlets observed in the ritualistic head-to-tail spawning position (Fischer 1980b) were counted as a spawning event. In order to avoid recording the same spawning pair twice, each reef section was surveyed only once.

(d) Behavioural observations to test for aggressive mimicry

Two SCUBA divers observed 12 butter hamlets (H. unicolor), the putative aggressive mimic, in the wild during observation intervals lasting 45–60 min in Bocas del Toro in February and March 2006. The same observation methods and times were also employed to independently track 12 barred hamlets (H. puella), which we used as the experimental control given that this colour morph does not resemble the foureye butterflyfish (C. capistratus), the putative model. Observations were performed between 08.40 and 14.10 at depths ranging from 11 to 43 feet. Time spent by H. unicolor tracking C. capistratus was recorded and the predatory strikes performed by H. unicolor while tracking C. capistratus and while swimming alone were counted. ‘Tracking’ was defined as H. unicolor actively staying within 30 cm of C. capistratus, with sharp changes in speed and/or direction in order to stay close to the putative model (video sequence l in electronic supplementary material). ‘Predatory strikes’ were defined as sharp and long accelerations performed by H. unicolor (video sequence 2 in electronic supplementary material). Moreover, the time spent by H. unicolor in association with all other coral reef fishes and the number of predatory strikes performed during such associations was recorded.

A two-sided Mann–Whitney test was performed to test whether H. unicolor spent significantly more time tracking C. capistratus than did the control. A two-sided Wilcoxon signed ranks test was performed to test whether both H. unicolor and the control, H. puella, displayed significantly higher predatory activity while tracking C. capistratus versus when swimming alone. We tested whether the proportion of predatory strikes while tracking the putative model was significantly greater than the proportion of time spent tracking the putative model. Bonferroni corrections for multiple tests were applied to test the significance of p-values.

3. Results and discussion

Microsatellite analysis demonstrates highly significant genetic differences between all pairs of sympatric colour morphs (table 1). The absence of significant genetic differentiation between two samples of H. puella collected in Bocas del Toro in 2004 and 2005 empirically confirms that our methodology does not detect significant genetic differences in cases where none are anticipated. This constitutes the first evidence of consistent genetic differentiation between sympatric Hypoplectrus colour morphs.

Table 1.

Pairwise Fst estimates and test of genetic differentiation between Hypoplectrus puella, H. nigricans and H. unicolor from Belize, Bocas del Toro (Panama) and Barbados genotyped at 10 microsatellite loci. (Highly significant genetic differences were observed between all pairs of sympatric colour morphs tested except the control, H. puella collected in consecutive years in Panama. n, sample size; CI, confidence interval. Fst estimated following Weir & Cockerham (1984). Genetic differentiation tested with 10 000 permutations using G log-likelihood statistic (Goudet et al. 1996). *, **, ***significant p-value at the 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 levels, respectively.)

| H. puella/H. nigricans | H. puella/H. nigricans | H. puella/H. nigricans | H. unicolor/H. puella | H. unicolor/H. nigricans | H. puella/H. puella | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbados | Panama | Belize | Panama | Panama | Panama | |

| n=50/n=46 | n=50/n=50 | n=50/n=50 | n=40/n=50 | n=40/n=50 | n=50/n=35 | |

| locus | 2005/2005 | 2004/2004 | 2004/2004 | 2004/2004 | 2004/2004 | 2004/2005 |

| E2 | 0.001** | 0.009* | 0.014 | 0.023* | 0.023*** | −0.005 |

| Gag010 | 0.033*** | 0.016 | 0.028*** | 0.007 | 0.025*** | 0.005 |

| Hyp001 | 0.055*** | 0.003 | 0.033** | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.003 |

| Hyp015 | 0.027*** | −0.011 | −0.003 | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.009 |

| G2 | 0.027*** | 0.026*** | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.028*** | 0.002 |

| H24 | 0.035*** | 0.077*** | 0.022** | 0.026** | 0.078*** | −0.002 |

| Hyp008b | 0.113*** | 0.029** | 0.018* | 0.001 | 0.066*** | 0.009 |

| Hyp016 | 0.079*** | 0.042*** | 0.004 | 0.025*** | 0.029*** | 0.002* |

| Hyp018 | 0.000 | −0.007 | −0.003 | 0.007 | 0.024 | −0.001 |

| Pam013 | 0.017*** | 0.011*** | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.016*** | 0.004 |

| overall | 0.042*** | 0.023*** | 0.013*** | 0.010*** | 0.032*** | 0.001 |

| 95% CI | 0.022–0.064 | 0.008–0.039 | 0.005–0.020 | 0.004–0.017 | 0.018–0.048 | −0.002–0.004 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0778 |

Spawning observations carried out on the same populations analysed genetically show that the assortative pairing of hamlets observed by Fischer (1980a) translates to assortative mating, with 247 out of 251 (98.4%) independent spawning events occurring between two individuals of the same colour morph (table 2 and §2). Different colour morphs were recurrently seen in close proximity during spawning observations, thereby discounting habitat selection as a possible cause of assortative mating. A total of 180 transects covering 72 000 m2 of reef revealed considerable variation between sites in relative densities of hamlet colour morphs (figure 1), and in conjunction with the spawning observations indicate that hamlets mate assortatively even when rare (table 2 and §2). For example, yellowbelly hamlets (Hypoplectrus aberrans) from Bocas del Toro were observed spawning assortatively, despite a density estimated to one individual per 16 000 m2 of reef in the area.

Table 2.

Spawning observations of Hypoplectrus in Belize, Panama and Barbados. Of 251 spawnings observed, 247 were assortative with respect to colour pattern.

| colour morph 1 | H. puella | H. nigricans | H. aberrans | H. unicolor | H. indigo | H. chlorurus | H. puella | H. aberrans | H. nigricans | tan hamlet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| colour morph 2 | H. puella | H. nigricans | H. aberrans | H. unicolor | H. indigo | H. chlorurus | H. nigricans | H. puella | H. aberrans | H. nigricans | total |

| Belize | 1 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| Bocas del Toro | 58 | 31 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101 |

| Kuna Yala | 65 | 20 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 107 |

| Barbados | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| total | 132 | 78 | 19 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 251 |

Spawning observations show that colour pattern and mate choice are tightly associated. This suggests that colour pattern is the cue for assortative mating, especially in this system where no ecological, behavioural or morphological trait other than colour pattern has been shown to clearly distinguish the different hamlet morphs (Randall 1983; Böhlke & Chaplin 1993). Formal demonstration that colour pattern is the cue for assortative mating is beyond the scope of this study and is not expected to be an easy task for several reasons. Experiments under monochromatic light typically used to establish that colour alone cues a behavioural response (e.g. Seehausen & van Alphen 1998) would not be entirely satisfying, given that patterns such as bars, lines and spots (figure 1), in addition to colour, are likely to be an important phenotypic aspect of mate recognition. Moreover, hamlets engage in an elaborate courtship (Fischer 1980b) that renders the use of artificial models difficult. Finally, colour pattern manipulation would be challenging owing to the complexity of hamlet colour patterns (figure 1). In the absence of additional experiments, colour pattern represents the best hypothetical cue for the high colour fidelity of mating hamlets.

Notwithstanding the strong assortative mating observed among hamlets, table 2 establishes that 4 out of 256 (1.6%) spawning events occurred between different Hypoplectrus colour morphs. Interestingly, three out of these four spawning events occurred between colour morphs that were locally abundant (table 2 and figure 1), suggesting that there is no straightforward relation between spawning behaviour and colour morph densities. The occurrence of spawning events between different colour morphs in the wild, as well as the occasional occurrence of individuals with intermediate colour patterns, suggests the potential for gene flow between morphs. The analysis of individual microsatellite loci reveals that H24 is the only locus out of 10 systematically demonstrating highly significant differences between colour morphs. This genetic pattern is consistent with a scenario of speciation with gene flow where only a fraction of the genome—presumably linked to an ecological trait under selection—is systematically differentiated (Campbell & Bernatchez 2004). Given our limited assessment of the Hypoplectrus genome, we do not mean to imply that a single gene linked to H24 is responsible for speciation in hamlets, and additional genetic data are required to investigate the genetic architecture in Hypoplectrus. Complexes of multiple genes rather than a single gene are actually expected to underlie speciation in hamlets as colour pattern could result from the combination of several characters, and is shown here to be associated with complex foraging and spawning behaviours.

Altogether, spawning observations and microsatellite data show that although extremely closely related, sympatric Hypoplectrus colour morphs are reproductively isolated and can therefore be considered incipient species. Furthermore, the data on assortative mating provide the first line of evidence that colour pattern might be a phenotypic trait of the sort envisioned by Maynard Smith (1966) when he considered conditions under which speciation might proceed in the face of gene flow. But is hamlet colour pattern also under disruptive selection?

Randall & Randall (1960), followed by Thresher (1978), suggested that hamlet colour morphs evolved as aggressive mimics. According to this hypothesis, predatory hamlets that match the colour pattern of non-predatory coral reef fishes have a fitness advantage resulting from increased success approaching and attacking their prey. Although behavioural confirmation of aggressive mimicry has been lacking, Randall & Randall (1960) and Thresher (1978) identified seven putative mimic–model pairs suggesting, in principle, the possibility that disruptive selection on colour pattern to match models established the colour differences between hamlets.

Although disruptive selection on hamlet colour pattern may result from other ecological mechanisms such as crypsis (notably in H. puella and Hypoplectrus indigo, Thresher 1978; Fischer 1980a), the sheer number of putative mimic–model pairs called for an empirical test of the hypothesis of aggressive mimicry. Aggressive mimicry requires that: (i) the colour pattern of mimic and model match (Randall & Randall 1960; Thresher 1978), (ii) the mimic is rare relative to its model (Bates 1862; Randall & Randall 1960; Thresher 1978; Cheney & Côté 2005), (iii) the mimic spends more time with its model than expected by chance, and (iv) the mimic shows increased predatory activity when associated with its model (Côté & Cheney 2004). Considering that aggressive mimicry is a density-dependent mechanism which can be efficient exclusively when the mimic is rare compared with the model, as well as the substantial variation in colour morphs densities both within and between locations (figure 1), it seems that only a fraction of all putative mimics can actually benefit from aggressive mimicry at each location.

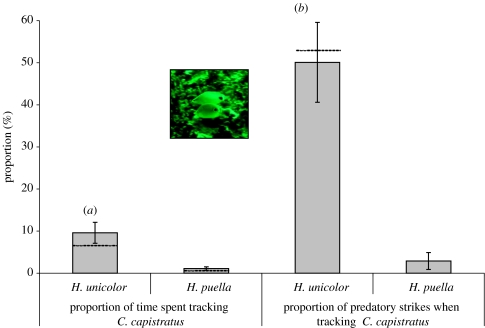

We focused our behavioural observations on H. unicolor because it closely resembles the non-predatory foureye butterflyfish, C. capistratus (figure 2, inset, and video sequences in electronic supplementary material), thus satisfying expectation one. Furthermore, although sufficiently abundant to permit efficient field observations at our principal study site in Bocas del Toro, it was 20 times less frequent in our transects than its putative model (mean density±s.e.=2.4±0.3 and 0.1±0.03 individuals/100 m2 for C. capistratus and H. unicolor, respectively), thus matching expectation two. Underwater observation for 19 h using SCUBA showed that H. unicolor spent a significantly higher proportion of its time tracking C. capistratus than did the experimental control H. puella (Mann–Whitney test, p-value<0.001, figure 2), and was more active as a predator in association with C. capistratus (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, p-value=0.005, figure 2). In contrast, the control H. puella showed no significant difference in predatory activity in or out of association with C. capistratus (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, p-value=0.385). Not counting time spent with C. capistratus, H. unicolor spent less than 1% of its time in association with all other coral reef fish species pooled together, and performed 1.2% of its predatory strikes during these intervals. In sum, H. unicolor spent 10% of its time tracking C. capistratus and executed 50% of all predatory strikes within that time (figure 2), thus satisfying the third and fourth conditions required for aggressive mimicry.

Figure 2.

(a) Proportion of time spent by H. unicolor tracking its putative model, the foureye butterflyfish (C. capistratus). (b) Proportion of predatory strikes performed by H. unicolor while tracking C. capistratus versus while swimming alone. Hypoplectrus puella served as the control for both analyses. Means±s.e., dashed lines: medians, n=12 observations of 45–60 min for each species. Inset: H. unicolor (above) and C. capistratus (below).

Our study permits strong inference that colour pattern is both the cue for assortative mating and subject to natural disruptive selection. Maynard Smith (1966) pointed out 40 years ago that such traits can trigger the evolution of reproductive isolation, but considered their occurrence ‘very unlikely’. Since then, such phenotypic traits have been documented in a limited number of cases (e.g. Nagel & Schluter 1998; Jiggins et al. 2001; Podos 2001), but both theoretical (Moore 1981; Slatkin 1982; Dieckmann & Doebeli 1999; Kirkpatrick 2000; Gavrilets 2004; Schneider & Bürger 2006) and experimental (Rice & Salt 1988, 1990) studies have shown that they offer one of the most plausible paths for speciation in the presence of gene flow. A question raised more recently by single trait models is whether speciation in the presence of gene flow is still possible when the costs of assortative mating are taken into account (Gavrilets 2004; Schneider & Bürger 2006). Our data show that incipient speciation is occurring, despite the fact that assortative mating is expected to be costly for rare colour morphs due to the difficulty of finding mates (e.g. H. aberrans in Bocas del Toro, figure 1). This study demonstrates that sympatric colour morphs of the genus Hypoplectrus are incipient species, and establishes a mechanism by which colour pattern can play an important role in marine speciation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the governments and authorities of Belize, Panama, Barbados and Kuna Yala for permits and support of our research. The Smithsonian Marine Science Network provided financial support for our investigation and Oscar Puebla was supported by graduate fellowships from the Levinson Family, Astroff-Buckshon Family and McGill University. The authors also thank Paul Humann for permission to use his published photographs and Jesus Mavarez as well as anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, tables, discussion, references and video sequence legends

Illustration of the behavioural pattern considered as ‘tracking’ in the present study. Putative mimic H. unicolor presents clear changes in speed and/or direction in order to stay within approximately 30<ce:hsp sp="0.25"/>cm of two C. capistratus putative models. This sequence would be considered as 24<ce:hsp sp="0.25"/>s of ‘tracking’ in our study

Illustration of the behavioural pattern considered as ‘predatory strike’ in the present study. H. unicolor performs a clear, sharp, and long acceleration. Note that the strike is performed close to a C. capistratus and that the prey, a small fish, is visible in this sequence. This sequence would be considered as one ‘predatory strike’ in the presence of C. capistratus in our study

References

- Acero A, Garzón-Ferreira J. Descripción de una especie nueva de Hypoplectrus (Pises: Serranidae) del caribe occidental y comentarios sobre las especies colombianas del genero. An. Inst. Invest. Mar. Punat Betín. 1994;23:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bates H.W. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon valley. Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1862;23:495–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham E, Banford H, Martin A.P, Aswani V. Smithsonian tropical research institute neotropical fish collections. In: Malabarba L, editor. Neotropical fish collections. Museu de Ciencias e Tecnologia, PUCRS; Puerto Alegre, Brazil: 1997. pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Böhlke J.E, Chaplin C.C.G. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 1993. Fishes of the Bahamas and adjacent tropical waters. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Bernatchez L. Generic scan using AFLP markers as a means to assess the role of directional selection in the divergence of sympatric whitefish ecotypes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:945–956. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh101. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney K.L, Côté I. Frequency-dependent success of aggressive mimics in a cleaning symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:2635–2639. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3256. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté I, Cheney K.L. Distance-dependent costs and benefits of aggressive mimicry in a cleaning symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:2627–2630. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2904. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cott H.B. Methuen & Co. Ltd; London, UK: 1940. Adaptive coloration in animals. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann U, Doebeli M. On the origin of species by sympatric speciation. Nature. 1999;400:354–357. doi: 10.1038/22521. doi:10.1038/22521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domeier M.L. Speciation in the serranid fish Hypoplectrus. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1994;54:103–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E.A. Speciation in the hamlets (Hypoplectrus: Serranidae)— a continuing enigma. Copeia. 1980a;1980:649–659. doi:10.2307/1444441 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E.A. The relationship between mating system and simultaneous hermaphroditism in the coral reef fish, Hypoplectrus nigricans (Serranidae) Anim. Behav. 1980b;28:620–633. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(80)80070-4 [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Machado E, Chevalier Monteagudo P.P, Solignac M. Lack of mtDNA differentiation among hamlets (Hypoplectrus, Serranidae) Mar. Biol. 2004;144:147–152. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1170-0 [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilets S. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2004. Fitness landscapes and the origin of species. [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J, Raymond M, de Meeüs T, Rousset F. Testing differentiation in diploid populations. Genetics. 1996;144:1933–1940. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves J.E, Rosenblatt R.H. Genetic relationships of the color morphs of the serranid fish Hypoplectrus unicolor. Evolution. 1980;34:240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04812.x. doi:10.2307/2407388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiggins C.D, Naisbit R.E, Coe R.L, Mallet J. Reproductive isolation caused by colour pattern mimicry. Nature. 2001;411:302–305. doi: 10.1038/35077075. doi:10.1038/35077075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan D.S, Evermann B.W. The fishes of North and Middle America. Bull. US Nat. Mus. 1896;47:1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M. Reinforcment and divergence under assortative mating. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2000;267:1649–1655. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1191. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K. Methuen; London, UK: 1966. On aggression. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith J. Sympatric speciation. Am. Nat. 1966;100:637–650. doi:10.1086/282457 [Google Scholar]

- McCartney M.A, Acevedo J, Heredia C, Rico C, Quenoville B, Bermingham E, Mcmillan W.O. Genetic mosaic in a marine species flock. Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:2963–2973. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01946.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan W.O, Weigt L.A, Palumbi S.R. Color pattern evolution, assortative mating, and genetic differentiation in brightly colored butterflyfishes (Chaetodontidae) Evolution. 1999;53:247–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05350.x. doi:10.2307/2640937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W.S. Assortative mating genes selected along a gradient. Heredity. 1981;46:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel L, Schluter D. Body size, natural selection, and speciation in sticklebacks. Evolution. 1998;52:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb05154.x. doi:10.2307/2410936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podos J. Correlated evolution of morphology and vocal signal structure in Darwin's finches. Nature. 2001;409:185–188. doi: 10.1038/35051570. doi:10.1038/35051570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poey E. Memorias sobre la historia natural de la isla de Cuba. Havana. 1852;1:1–463. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon M.L, Lobel P.S, Sorenson M.D. Lack of mitochondrial genetic structure in hamlets (Hypoplectrus spp.): recent speciation or ongoing hybridization? Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:2975–2980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01966.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall J.E. T. F. H. Publications; Neptune City, NJ: 1983. Caribbean reef fishes. [Google Scholar]

- Randall J.E, Randall H.A. Examples of mimicry and protective resemblance in tropical marine fishes. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1960;10:444–480. [Google Scholar]

- Rice R.W, Salt G.W. Speciation via disruptive selection on habitat preference: experimental evidence. Am. Nat. 1988;131:911–917. doi:10.1086/284831 [Google Scholar]

- Rice R.W, Salt G.W. The evolution of reproductive isolation as a correlated character under sympatric condition: experimental evidence. Evolution. 1990;44:1140–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05221.x. doi:10.2307/2409278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K.A, Bürger R. Does competitive divergence occur if assortative mating is costly? J. Evol. Biol. 2006;19:570–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01001.x. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O, van Alphen J.J.M. The effect of male coloration on female mate choice in closely related Lake Victoria cichlids (Haplochromis nyererei complex) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1998;42:1–8. doi:10.1007/s002650050405 [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. Pleiotropy and parapatric speciation. Evolution. 1982;36:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1982.tb05040.x. doi:10.2307/2408044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thresher R.E. Polymorphism, mimicry, and the evolution of the hamlets (Hypoplectrus, Serranidae) Bull. Mar. Sci. 1978;28:345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Weir B.S, Cockerham C.C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984;38:1358–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x. doi:10.2307/2408641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods, tables, discussion, references and video sequence legends

Illustration of the behavioural pattern considered as ‘tracking’ in the present study. Putative mimic H. unicolor presents clear changes in speed and/or direction in order to stay within approximately 30<ce:hsp sp="0.25"/>cm of two C. capistratus putative models. This sequence would be considered as 24<ce:hsp sp="0.25"/>s of ‘tracking’ in our study

Illustration of the behavioural pattern considered as ‘predatory strike’ in the present study. H. unicolor performs a clear, sharp, and long acceleration. Note that the strike is performed close to a C. capistratus and that the prey, a small fish, is visible in this sequence. This sequence would be considered as one ‘predatory strike’ in the presence of C. capistratus in our study