Abstract

K/B×N T cell receptor transgenic mice are a model of inflammatory arthritis, most similar to rheumatoid arthritis, that is critically dependent on both T and B lymphocytes. Transfer of serum, or just immunoglobulins, from arthritic K/B×N animals into healthy recipients provokes arthritis efficiently, rapidly, and with high penetrance. We have explored the genetic heterogeneity in the response to serum transfer, thereby focussing on the end-stage effector phase of arthritis, leap-frogging the initiating events. Inbred mouse strains showed clear variability in their responses. A few were entirely refractory to disease induction, and those which did develop disease exhibited a range of severities. F1 analyses suggested that in most cases susceptibility was controlled in a polygenic additive fashion. One responder/nonresponder pair (C57Bl/6 × NOD) was studied in detail via a genome scan of F2 mice; supplementary information was provided by the examination of knock-out and congenic strains. Two genomic regions that are major, additive determinants of the rapidity and severity of K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis were highlighted. Concerning the first region, on proximal chromosome (chr)2, candidate assignment to the complement gene C5 was confirmed by both strain segregation analysis and functional data. Concerning the second, on distal chr1, coinciding with the Sle1 locus implicated in susceptibility to lupus-like autoimmune disease, a contribution by the fcgr2 candidate gene was excluded. Two other regions, on chr12 and chr18 may also contribute to susceptibility to serum-transferred arthritis, albeit to a more limited degree. The contributions of these loci are additive, but gene dosage effects at the C5 locus are such that it largely dominates. The clarity of these results argues that our focus on the terminal effector phase of arthritis in the K/B×N model will bear fruit.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, animal model, genetics, complement, autoimmunity

Introduction

Somewhat surprisingly for a disease of such prevalence, the etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remain poorly understood. The diarthrodial joint lesion is marked by hypertrophy of the synovial lining and leukocyte infiltration of the synovium and the joint cavity, leading to erosion and eventual destruction of cartilage and bone. The arthritic process clearly involves an inflammatory cascade, probably pursuant to an initiating immune response. Yet what activates the inflammatory cascade in a joint-specific manner resulting in RA remains obscure: a genetic lesion? some microbial insult? a combination of the two? Also cloudy is whether the initiating event is systemic or joint directed.

A number of groups have attempted to harness the power of genetic analysis to dissect the arthritic process (for a review, see reference 1). The high prevalence of RA in sibs or twins of affected individuals, its known familial aggregation, and patterns of inheritance suggest inherited influences 2 3, prompting the organization of several large multicenter studies of genetic linkage in families of RA patients 4 5. Although promising in that a number of “suggestive” linkages were uncovered, these efforts failed to demonstrate reproducible significant linkage, implying that the underlying genetic complexity demands larger numbers of informative families and probably some type of patient stratification.

The identification of loci influencing RA in resemblant animal models could prove a significant aid for the human genetic studies. Recognizing this, multiple groups have reported a number of genetic dissections of collagen-, proteoglycan- or irritant-induced arthritis in rats or mice 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14. Here again, the picture that has emerged is one of great complexity, with up to eight regions scoring suggestively or significantly 8 13 although, interestingly, some of the highlighted chromosomal regions are syntenic between mice and rats 10. This complexity, as in the human studies, probably reflects the multiple steps and molecular pathways involved in a disease-like induced arthritis, for example, for collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), the immune response to injected collagen, translation of that response into joint inflammation, and the magnitude and persistence of the immune and inflammatory components over time. This multiplicity of events reads out as complexity in the inheritance patterns, lowers the signal-to-noise ratios in the analyses, and generally hinders our progression towards identifying heritable influences.

Genetic analyses of animal models of arthritis would no doubt be simplified and clarified by viewing discreet disease phases in isolation. A recently developed model of inflammatory arthritis, K/B×N TCR transgenic mice allows such a “phase separation.” This transgene encodes a TCR which confers reactivity to a self-peptide presented in the context of Ag7 class II molecules of the MHC. All K/B×N animals which carry both the transgene and the stimulatory MHC allele spontaneously develop an autoimmune disorder with most (although not all) of the clinical, histological, and immunological features of human RA patients 15. Though the murine disease appears to be exquisitely join specific, it is provoked by T cell reactivity to glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), an enzyme expressed in all cells and also found circulating in the blood 16. Anti-GPI T cell reactivity results in preferential activation of and help to those B lymphocytes whose Ig receptors recognize GPI and sequester the small amounts in circulation, resulting in massive production of anti-GPI Abs, which somehow provoke arthritis. Transfer of serum from arthritic K/B×N mice into healthy mice routinely provokes arthritis within days, even when the recipients are completely devoid of lymphocytes 17. This serum-transfer system has obvious attractions for genetic studies: it allows the rapid analysis of any chosen inbred, variant, or mutant mouse strain; it is robust, with essentially 100% incidence in susceptible strains; and it is simple, focussing on end-stage events, leap-frogging the earlier autoimmune initiation phases, potentially greatly reducing the complexity of the genetic analysis.

This report represents a broad genetic analysis of K/B×N serum-tranferred arthritis. We describe genetic heterogeneity in the response to K/B×N serum in inbred mouse strains and genetic intervals responsible for the difference in disease manifestation shown by the C57Bl/6 (B6) and NOD strains.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

For basic strain analysis, 4–5-wk-old male inbred B6, Balb/cByJ, Balb/cJ, PL, C57BL/10, DBA/1, CBA, MRL/Mp (MRL), NZW, C3H/He (C3H), SJL, 129/Sv, DBA/2, FvB/N, NZB, and various F1 hybrids (Balb/c × B6, B6 × C3H, Balb/c × SJL, B6 ×SJL, PL × SJL, and NZW × NZB) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. NOD/LtDOI, Balb/c × PL, Balb/c × NZW, C3H × NZW, MRL × Balb/c, B6 × NZW, NZW × SJL, C3H × SJL, and MRL × B6 were bred in our laboratory colony. F2 cohorts were generated from both B6 × NOD and NOD × B6 mating pairs, and both female and male offspring were tested at 5–6 wk of age. FcγRII−/− mice 18 on a mixed (B6 × 129) background and control (B6×129/SvImJ) F2 animals (FcγRII+/+) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. B6.NODfcgr2 congenic mice 19 were bred in the animal facility in Hopital Necker.

Serum Transfer Protocol and Arthritis Scoring.

K/B×N serum pools were prepared from arthritic mice at 60 d of age. Arthritis was induced in the diverse recipients by intraperitoneal injection (7.5 μl serum per g weight) in 200 μl total volume at days 0 and 2. A clinical index was evaluated over time: 1 point for each affected paw; and 0.5 point for a paw with only mild swelling/redness or only a few digits affected. Ankle thickness was measured by a caliper 17, ankle thickening being defined as the difference in ankle thickness vis a vis the day 0 measure.

Genetic Mapping and Statistical Analysis.

Tail genomic DNA was isolated from 132 (B6×NOD) F2 hybrids for PCR amplification with 163 primers specific for the C5 and fcgr2 loci and other microsatellite markers spanning the 19 autosomes of the mouse genome. The C5 primers, 5′-GGATTTTACAACAACTGGAACTGC-3′ and 5′-AAGCACTAGATACTCAAACAA-3′, flanking the 2-base pair (bp) deletion in the coding region of the NOD C5 gene were designed to amplify genomic fragment from both the NOD and B6 genomes 20 21. The fcgr2 primers were 5′-AGAATCTGAGAAACTTTGTT-3′ and 5′-TCGGTCTGTGCCCTAGTCCT-3′. These flank the 13-bp deletion in the promoter region of the fcgr2b gene in NOD mice 19 and result in 187- and 200-bp fragments with NOD and B6 genomic DNA, respectively. Amplification conditions: 92°C × 10 s, 45°C × 30 s, and 72°C × 30 s for 35 cycles. The D1Nds8 microsatellite marker was used to confirm the genetic position of the fcgr2 gene on chromosome (chr)1 22 23. The other 161 primers used for screening were selected from the MIT database (http://carbon.wi.mit.edu:8000/cgi-bin/mouse/index#genetic), spaced at about 10-cM intervals and efficiently discriminated the NOD and B6 alleles. For all DnMit markers, the PCR reaction volume was 20 μl containing 50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.50 mM each primer, 45 mM Tris (pH 8.8), 11 mM (NH4)2SO4 (pH 8.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 6.7 mM β-mercapto-ethanol, 4.5 mM EDTA, 65.2 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, and 0.4 U Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer). Thermocycling was initiated by 4 min of denaturation and followed by a touchdown protocol from either 60–55°C or 55–50°C. When possible, genotypes were visualized on a 4% agarose gel. For the remaining markers, PCR products were electrophoresed on standard denaturing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to positive-charged nylon membrane (Pall). The membranes were hybridized with a primer labeled with α-32[PdCTP] using terminal transferase (Boehringer). Genotypes were determined after autoradiography. (Discrepancies for several markers were noticed in polymorphism information provided for the two strains by the MIT database. The full listing of markers used in this study can be consulted at http://stage.joslin. org/research/DOI155).

Marker order and genetic distances were established with MapMaker/Exp3.0 24. After genetic map construction, genotypes were verified using any of two independent criteria: violation of recombination interference (with the help of MapManager/QT2.9 [reference 25] or automatic detection of errors with a threshold of 1% (MapMaker/Exp3.0). Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) were detected by interval mapping with MapManager/QTL1.1. The genome-wise significance of the findings was evaluated using thresholds suggested by Lander and Kruglyak 24. Contingency table analysis was applied in parallel, bringing out the suggestive locus on chr18 in particular. Analysis of the interactions between the QTLs was done both by fixing a QTL and looking at the change in LOD scores with MapMaker/QTL3.0 and by multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), and by multiple regression analysis (S-plus).

Results

Susceptibility to K/B×N Serum-transferred Arthritis in Inbred Mouse Strains.

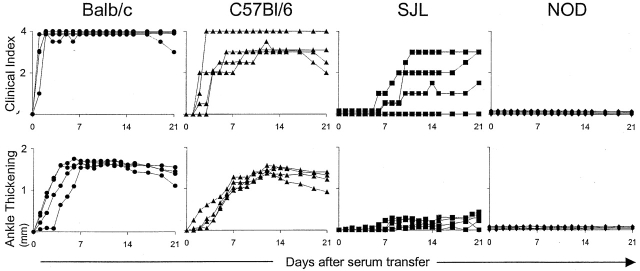

To evaluate the genetic heterogeneity in response to arthritogenic serum, we transferred a fixed dose of K/B×N serum into a panel of inbred mouse strains. These included standard laboratory lines as well as lines with a particular propensity for autoimmune or inflammatory disease. 4–5-wk-old males were injected with 7.5 μl/g of serum from 60-d-old arthritic K/B×N mice. Arthritis was evaluated over time by visual inspection of the limbs in order to derive a clinical index and by measurement of ankle thickness 15. The results are compiled in Table , and representative profiles for four of the strains are presented in Fig. 1. Four categories of response were observed. In hyperreactive strains (e.g., Balb/c), inflammation was visible already 24 h after serum injection and it rapidly attained maximal clinical index and ankle thickening values; these strains also exhibited the most extreme ankle swelling. Several of the strains (e.g., DBA/1, CBA) showed the lesser but still robust responses we previously observed with B6 mice, appearing after 3–4 d and affecting all limbs, with a marked increase in ankle thickness. With a third group (e.g., SJL, 129/Sv), responses were present but torpid, often affecting only one or two limbs and quite slow to reach maximal development. Finally, a fourth group (NOD, NZB, FvB/N, DBA/2) was completely resistant to disease transfer.

Table 1.

K/B×N Serum-transferred Arthritis in Diverse Inbred Strains

| Histological evaluation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Max. clinical index | Day of onset | Max. ankle thickening | No. of mice examined | Inflammation | Cartilage destruction |

| (mm) | ||||||

| Balb/c | 4.0 | 1.2 (1–2) | 1.5 | 11 | (++) | (++) |

| C57Bl/10 | 3.9 | 1.3 (1–3) | 1.4 | 4 | (++) | (+) |

| PL | 3.8 | 2.0 (1–4) | 1.4 | 8 | (++) | (++) |

| C57Bl/6 | 3.5 | 2.9 (1–6) | 1.5 | 19 | (++) | (+) |

| DBA/1 | 3.5 | 2.8 (2–5) | 1.4 | 4 | (+) | (+) |

| CBA | 3.5 | 3.5 (2–5) | 1.1 | 4 | (++) | (+) |

| MRL/Mp | 2.9 | 3.8 (2–4) | 0.9 | 4 | (++) | (+++) |

| NZW | 2.9 | 4.8 (1–14) | 0.7 | 4 | (++) | (+++) |

| C3H/He | 2.2 | 6.4 (3–12) | 1 | 5 | (+/−) | (+/−) |

| SJL | 2.2 | 12.4 (2–28) | 0.6 | 12 | (+) | (+/−) |

| 129/Sv | 1.6 | 3.5 (3–4) | 0.3 | 4 | (+/−) | (+/−) |

| DBA/2 | ND | ND | 0 | 4 | (−) | (−) |

| FvB/N | ND | ND | 0 | 4 | (−) | (−) |

| NZB | ND | ND | 0 | 4 | (−) | (−) |

| NOD | ND | ND | 0 | 4 | (−) | (−) |

Different strains of mice were transferred with 7.5 μl per gram body weight of serum from K/B×N mice on days 0 and 2. Two mice were killed at day 7 for histology, and the others followed until days 12–28. The “day of onset” is the first day of overt disease on one limb.

Figure 1.

Variable responses by diverse inbred strains to K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis. Mice of each strain (4–5-wk-old males) were injected with serum from arthritic K/B×N animals (7.5 μl per gram body weight) on days 0 and 2. Arthritis was evaluated by measuring “clinical index” and “ankle thickening” (see Materials and Methods) every day until day 21. Data from representative, multiple experiments are shown, each curve representing an individual mouse.

Results from histological analyses of limbs from injected mice largely correlated with the clinical indices (Table ). The strongest synovitis, inflammatory infiltration of the articular cavity, and cartilage destruction were observed in the strains that had the greatest joint involvement and ankle thickening. The only exceptions were the MRL/Mp and NZW strains which showed more extensive pannus formation and cartilage erosion than one might have expected from their clinical evaluation.

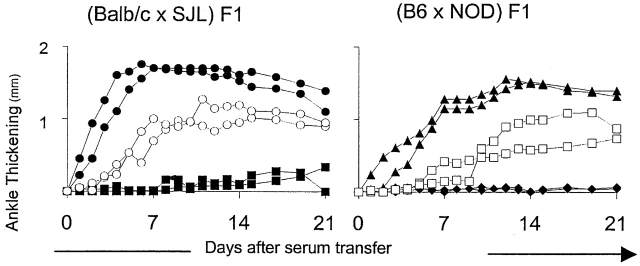

These findings pointed to significant heterogeneity within the Mus species in susceptibility to K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis. As a first step in dissecting the genetic basis of this heterogeneity, we generated a number of F1 hybrids between these strains and tested their response to transfer K/B×N serum (Fig. 2, Table ). Some of these crosses were designed to evaluate trait dominance by combining high responders with medium, low, or nonresponders. Several different outcomes were observed. (Balb/c × NZW) F1 mice took on the rapid responsiveness typical of the Balb/c parent suggesting a dominant accelerating Balb/c locus or loci. On the other hand, in Balb/c crosses to B6 or MRL the more typical responsiveness of the latter strains won out. Finally, the (Balb/c × SJL) F1s displayed an intermediate phenotype. In other crosses (C3H/He × SJL or NZW × NZB), low or nonresponders were combined in an attempt to reveal complementing loci. But this was not observed, these F1s remaining low responders; similarly, none of the F1s between intermediate responders could reproduce the very aggressive disease of the Balb/c strain.

Figure 2.

Susceptibility of F1 mice to K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis. (Balb/c × SJL) F1 and (B6 × NOD) F1 mice as well as the parental strains were tested by the procedure described in the legend to Fig. 1. Each panel shows data from a representative experiment of three. ○, (Balb/c × SJL) F1; •, Balb/c; ▪, SJL; □, (B6 × NOD) F1; ▴, B6; ♦, NOD.

Table 2.

Responses of Diverse Strain Combinations to K/B×N Serum

| Combination | Strain (F1) | Max. clinical index | Day of onset | Max. ankle thickening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm) | ||||

| Hi × Hi | Balb/c × PL | 4 | 1 (1) | 1.5 |

| Hi × M | Balb/c × NZW | 4 | 1 (1) | 1.4 |

| Balb/c × MRL | 2.8 | 3.5 (2–5) | 1.0 | |

| Balb/c × B6 | 2.5 | 2.5 (2–3) | 0.9 | |

| Hi × Lo | Balb/c × SJL | 2 | 3.7 (3–4) | 0.8 |

| PL × SJL | 1.1 | 5.8 (3–7) | 0.3 | |

| M × M | B6 × NZW | 2.5 | 4 (4) | 1.6 |

| B6 × MRL | 1 | 6.5 (6–7) | 0.4 | |

| M × Lo | NZW× C3H | 3.5 | 2.5 (2–3) | 1.6 |

| B6 × C3H | 2.5 | 2.5 (2–3) | 0.8 | |

| NZW × SJL | 2 | 3.5 (1–6) | 1.1 | |

| B6 × SJL | 1.8 | 5 (3–7) | 0.3 | |

| Lo × Lo | C3H × SJL | 1.3 | 6 (5–7) | 0.1 |

| M × Non | B6 × NOD | 2.5 | 4.2 (2–7) | 1.0 |

| NZW × NZB | 1 | 5.5 (4–7) | 0.2 |

Different strains of mice were transferred with 7.5 μl per gram body weight with serum from K/B×N mice on days 0 and 2. 2–10 mice were tested in each group. Mice were followed until day 7. In the “combination” column, Hi, M, Lo, and Non stand for high, moderate, low, and nonresponders, respectively. The “day of onset” is the first day of overt disease in one limb.

No simple genetic model can account for the diversity of phenotypes in the inbred strains and their hybrids. Several genes and alleles must be segregating.

Phenotype Analysis in (B6 × NOD) F2 Hybrids.

Next, we chose a responder/nonresponder pair for a phenotypic/genotypic analysis in an F2 intercross, the (B6 × NOD) combination, because i) it is a strain pair that has been studied previously in the context of autoimmune diabetes and for which reliable polymorphic microsatellite marker sets are available; ii) disease incidence is high and reproducible in the B6 strain, which is the prototype strain used in many transgenic manipulations and for which genome sequence data should soon be available; and iii) although we know that the NOD genetic background is not absolutely required for disease development 15, the propensity of the NOD strain to autoimmune disease might prove relevant in the present context.

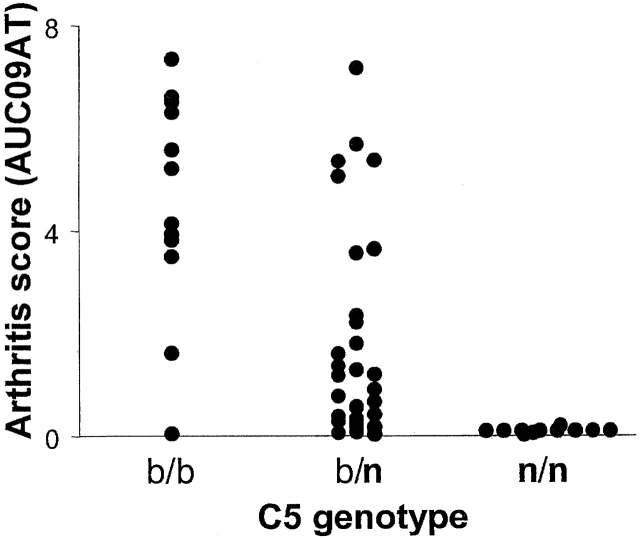

A preliminary set of 56 (B6 × NOD) F2 mice was bred and tested for response to transfer of K/B×N serum. A wide range of phenotypes was observed (Fig. 3), ranging from a complete lack of response to full responsiveness. There were no sex-related differences (AUCAT0-9 of 5.94 ± 3.17 and 5.00 ± 3.22 in males and females, respectively). Analogous to the situation with CIA 26 27, we suspected that the locus encoding the C5 fraction of complement might be involved in the differential susceptibility of F2 mice to K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis, particularly since NOD mice are C5 deficient due to a 2-bp deletion in the coding region of the C5 locus 21. Therefore, we typed the F2 mice for this trait; the results presented in Fig. 3 are partitioned according to genotype at the C5 locus. Homozygosity for the NOD-derived C5 allele (n/n) totally prevented arthritis transfer. This finding is substantiated by the strain distribution of susceptibility to K/B×N serum (Table ): all of the four nonresponder strains (NOD, FvB/N, NZB, DBA/2) are C5 deficient 20, while all the strains that showed some degree of responsiveness are C5 proficient. Also evident was a gene-dosage effect of the B6-derived allele; disease was usually more severe in b/b homozygotes than in b/n heterozygotes.

Figure 3.

Responses of mice of different C5 genotypes to transfer of K/B×N serum. In this pilot experiment, 56 (B6 × NOD) F2 mice were followed by measuring ankle thickness (see Materials and Methods) after K/B×N serum transfer. The arthritis score was read out as “AUC09AT,” the integral of ankle swelling between 0 and 9 d after transfer, a composite measure of disease rapidity and severity. Each point represents the response of an individual mouse. Animals were also genotyped via PCR to identify the inactivating 2-bp deletion at the C5 locus, derived from the NOD genome; results are plotted according to the C5 genotype.

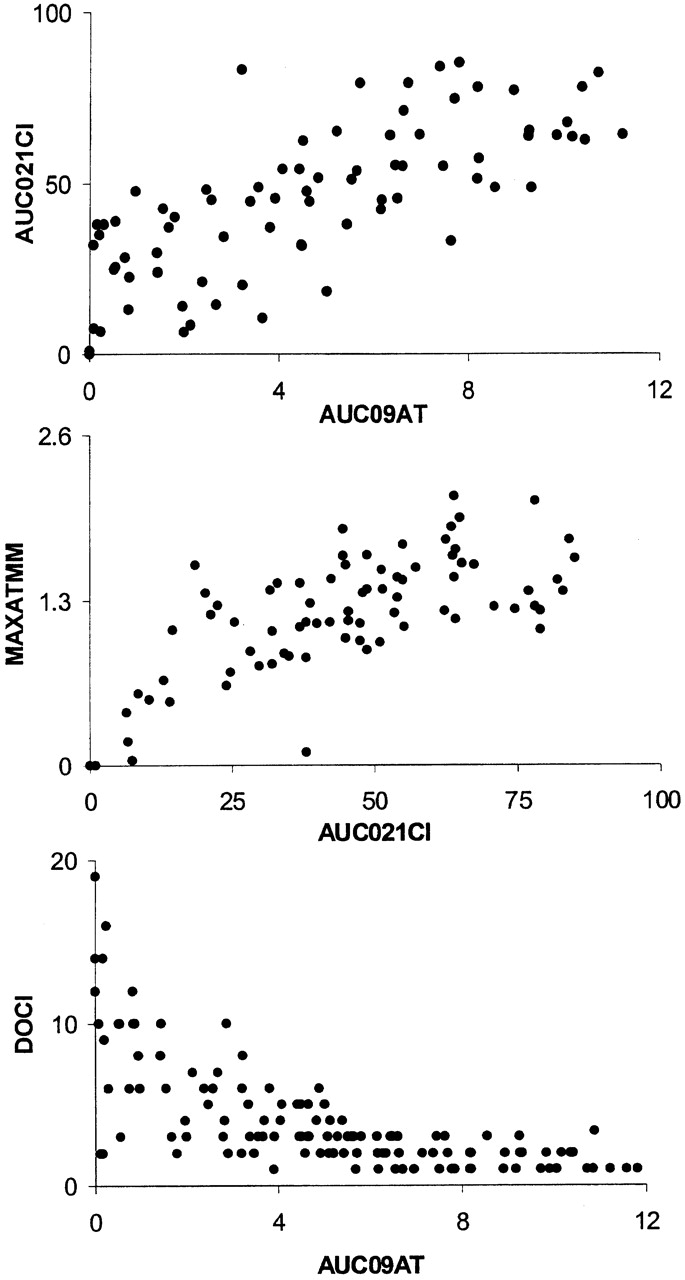

On the basis of these preliminary data, there being little point in testing resistant C5 n/n mice, we transferred K/B×N serum to a cohort of 132 F2 mice that had been preselected for carrying b/b or b/n genotypes at the C5 locus. As in the pilot group, a wide range of responses was seen. 92.4% showed at least some disease manifestations, and 7.6% did not. In a recent analysis of susceptibility to pristane-induced arthritis in rats 13, it was found that different loci controlled different parameters of the animals' response: severity, speed of onset, and chronicity behaved as independent quantitative traits (QTs). To test whether similar differences are found in the K/B×N serum-induced disease, we converted our clinical observations on the F2 recipients to several independent QTs; DOCI, the day of onset of clinically detectable disease, a measure of response speed; MAXATMM, the maximum degree of ankle swelling, a measure of severity; AUC0-9AT, the integral of ankle swelling up to day 9 after transfer, a composite measure of disease rapidity and severity; and AUC0-21CI, the integral of the clinical index up to day 21 after serum transfer, a composite measure incorporating disease aggressiveness and persistence. (In the K/B×N serum-transfer model, disease usually wanes slowly after 2 wk, without establishment of a chronic state).

Genetic Mapping in the (B6 × NOD) Combination.

Results for the 132 mice of the (B6 × NOD) F2 cohort are presented in Fig. 4 as a set of two-parameter plots correlating the various indices. Clearly, all disease parameters were correlated, and there was no indication of genotypes preferentially affecting speed or severity. This visual evaluation was confirmed by cluster analysis and principal components (data not shown; Statistica).

Figure 4.

Correlations between different QTs. 132 (B6 × NOD) F2 mice with at least one functional C5 allele from the B6 genome were injected with K/B×N serum. Arthritis development was read out as four distinct QTs: MAXATMM, the maximum degree of ankle swelling, is a measure of severity; AUC09AT, the integral of ankle swelling up to day 9 after transfer, a composite measure of disease rapidity and severity; AUC021CI, the integral of the clinical index in the 21 d after serum transfer, a composite measure of disease aggressiveness and persistence; DOCI, the day of onset of clinically detectable disease, a measure of response speed. Two-parameter representations of these traits are shown. Each point corresponds to an individual mouse.

The mice were then typed for a set of 162 informative microsatellite markers selected from our previous analyses 28 and from the MIT database (http://carbon.wi.mit.edu:8000/cgi-bin/mouse/index#genetic), verified for polymorphism between our NOD and B6 strains. These markers gave 87.5% coverage of the mouse genome based on 10-cM intervals, with an average spacing of 7.84 cM between markers. The marker list and full genotype data are accessible at http://stage.joslin.org/research/DOI155.

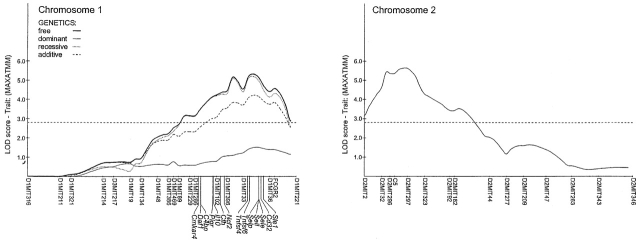

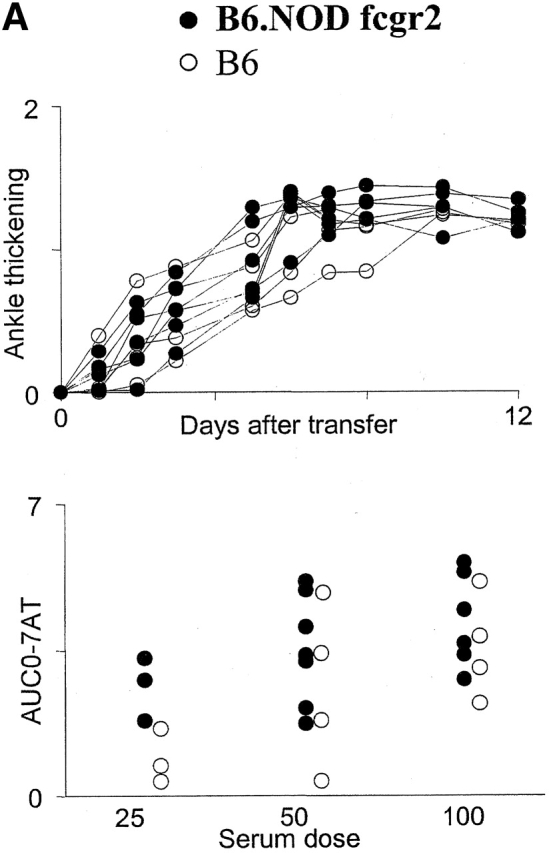

The genotypic data were analyzed by Mapmaker/QTL. Two major QTLs were found, and these stood out with all QTs tested (Table ; graphic representation in Fig. 5). One is centered at the C5 locus on chr2, confirming the difference in distribution between b/b and b/n genotypes seen in the preliminary study (Fig. 3). The functional C5b allele enhances severity in a gene-dose–dependent fashion. The other strong locus is on chr1, roughly centered around the D1MIT33 marker (95% confidence interval 79.0–92.3 cM). Severity is associated with the NOD-derived allele, which behaves as “partially dominant.” The NOD strain carries a mutation in the gene encoding the inhibitory receptor for IgG, FcγRII, which prevents efficient signaling upon Ig engagement 19. Although the fcgr2 locus appeared slightly outside the peak linkage interval on the chromosome map (Fig. 5), it was important to ascertain its possible contribution to the phenotype. Two lines of mice were employed to this end: i) the B6.NODfcgr2 congenic line, which carries the NOD allele of fcgr2 on the B6 background 19; and ii) the FcγRII−/− line, which harbors a knockout mutation of the fcgr2 gene 18, this mutation rendering normally resistant H-2b mice susceptible to CIA 29. Both of these lines were tested in time-course studies, and in response to graded doses of K/B×N serum. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the enhanced severity imparted by the NOD chr1 interval in F2 mice was not reproduced by the NOD fcgr2 congenic interval. In addition, knockout of fcgr2 had no apparent effect on disease, neither a positive nor a negative one. These results strongly suggest that fcgr2 is not responsible for the chr1 effect we have detected. This analysis also puts a right boundary on the interval, which must map to the left of the 87.9–112 cM congenic interval in B6.NODfcgr2.

Table 3.

Mapmaker LOD Scores for Different Markers

| AUC09AT | MAXATMM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD | P | LOD | P | |

| D1MIT134 | 1.3 | 0.04481 | ||

| D1MIT48 | 2.3 | 0.00483 | 2.0 | 0.00891 |

| D1MIT386 | 2.6 | 0.00249 | 2.2 | 0.00580 |

| D1MIT469 | 2.8 | 0.00169 | 2.5 | 0.00294 |

| D1MIT89 | 2.7 | 0.00209 | 2.7 | 0.00189 |

| D1MIT229 | 3.0 | 0.00100 | 3.2 | 0.00069 |

| D1MIT286 | 3.0 | 0.00100 | 3.2 | 0.00069 |

| D1MIT102 | 3.8 | 0.00018 | 4.2 | 5.7e-5 |

| D1MIT396 | 3.9 | 0.00013 | 4.4 | 3.7e-5 |

| D1MIT33 | 4.0 | 9.3e-5 | 4.5 | 2.8e-5 |

| D1MIT36 | 3.9 | 0.00014 | 4.4 | 3.8e-5 |

| FCGR2 | 3.5 | 0.00031 | 4.6 | 2.6e-5 |

| D1MIT221 | 1.8 | 0.01497 | 2.4 | 0.00412 |

| D2MIT2 | 3.6 | 0.00027 | 3.1 | 0.00075 |

| D2MIT32 | 5.7 | 2.0e-6 | 4.6 | 2.4e-5 |

| D2MIT296 | 7.0 | 9.4e-8 | 5.4 | 4.3e-6 |

| C5 | 7.0 | 1.2e-7 | 5.4 | 4.4e-6 |

| D2MIT297 | 6.1 | 8.7e-7 | 5.6 | 2.3e-6 |

| D2MIT323 | 5.8 | 1.7e-6 | 4.3 | 5.4e-5 |

| D2MIT92 | 3.8 | 0.00018 | 3.4 | 0.00038 |

| D2MIT182 | 3.6 | 0.00023 | 3.3 | 0.00047 |

| D2MIT44 | 2.4 | 0.00406 | 2.0 | 0.01012 |

| D2MIT277 | 1.9 | 0.01377 | ||

| D2MIT209 | 1.9 | 0.01348 | 1.6 | 0.02458 |

| D2MIT47 | 1.5 | 0.03414 | 1.4 | 0.03987 |

| D12MIT136 | 1.9 | 0.01180 | ||

| D12MIT109 | 1.7 | 0.02220 | ||

| D12MIT156 | 2.6 | 0.00250 | 1.8 | 0.01485 |

| D12MIT158 | 1.8 | 0.01686 | 1.7 | 0.02040 |

| D14MIT133 | 1.5 | 0.03113 | ||

| D14MIT141 | 1.7 | 0.02292 | ||

| D14MIT193 | 1.9 | 0.01388 | ||

| D18MIT21 | 1.5 | 0.02923 | ||

| D18MIT60 | 1.8 | 0.01422 | 2.3 | 0.00446 |

| D18MIT123 | 1.5 | 0.03491 | 1.3 | 0.04897 |

LOD scores >3 are shown in bold type.

Figure 5.

Chromosome susceptibility plots. MAPMAKER LOD score curves from the (B6×NOD) F2 whole genome scan for chr1 and 2 (Fig. 4). For chr1, all four traces are shown (MAPMAKER run along free, dominant, recessive, and additive models; note that significant LOD scores are obtained with the recessive, but not the dominant, model. For chr2, only the dominant model was warranted since n/n homozygotes are not included in the analysis. The positions (mouse genome database) of several candidate genes within the interval of interest are shown.

Figure 6.

Lack of influence of the fcgr2 locus on susceptibility to K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis. (A) Congenic strain analysis. (Top) B6.NODfcgr2 (•) or B6 (○) mice were injected with serum from arthritic K/B×N mice, and ankle thickness was followed over time; each line represents an individual mouse. (Bottom) A group of mice was challenged with limiting doses of serum, and the arthritis score was measured over the next 4 d (AUC-07AT; each dot represents an individual mouse). (B) Knockout analysis. Fcgr2-deficient mice (▴) or control (B6 × 129) F2 mice (▵) were treated as in A and followed for ankle swelling over time, or in dose–response experiments, again as in A.

No other locus exhibited a comparable degree of linkage in the Mapmaker/QTL analysis. Two other regions (chr12, 19–38 cM, chr18, 4–20 cM) showed marginal evidence of linkage according to the criteria, proposed by Lander and Kruglyak 24.

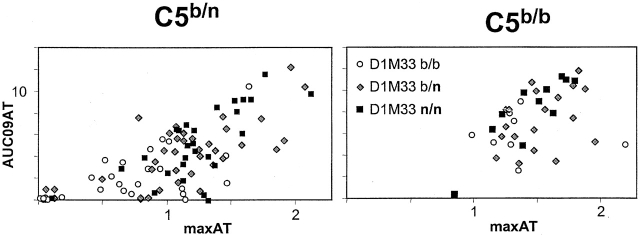

Finally, potential epistatic interactions between the loci were sought. As graphically illustrated in Fig. 7, which partitions animals according to C5b homo/heterozygosity and according to the D1MIT33 marker on chr1, the C5b locus has a dominating effect, such that the majority of C5b/b mice, no matter the D1MIT33 status, are high responders. The impact of the chr1 region appears less obvious than in C5 heterozygotes. However, multiple regression analysis did not provide support for interaction between C5 and D1MIT33, consistent with a simple additive model.

Figure 7.

Influence of the C5 locus on the rapidity/severity of K/B×N serum-transferred arthritis. The results from the (B6 × NOD) F2 analysis of Fig. 4 are represented after segregating the mice into C5 b/n heterozygotes (left) or C5 b/b homozygotes (right); all C5n/n mice are fully resistant to disease and are not represented. Within these two groups, mice of different genotypes at D1MIT33 are represented by different symbols. Note how the C5 locus alone has a major influence on severity, such that the effect of the D1MIT33 genotype, readily apparent in C5b/n mice, is far less obvious in C5b/b animals.

Discussion

We have exploited the K/B×N serum-transfer system to survey and dissect genetic influences on end-stage effector processes during the unfolding of inflammatory arthritis. The rapid, robust, repeatable character of the K/B×N serum-induced disease has allowed a straightforward genetic examination, living up to our expectations on several counts.

First, the experimental system permitted the expedient study of a large panel of inbred mouse strains, which is usually impossible with murine models of autoimmune disease, for which only a limited set of strains can usually be assayed. For example, the NOD strain is one obligate partner in genetic studies on autoimmune diabetes, and experiments on CIA are restricted to mice of the H-2 haplotype that confers responsiveness to the eliciting antigen, primarily H-2q 30. Precedents from the genetic analyses of autoimmune diabetes have underlined the importance of assessing the genetic variance for a number of strains. While, for simplicity and as a “proof of principle,” we chose to focus on one particular strain combination in this study, examination of a large sampling of genetic variance will be required to generate a picture that can be compared with outbred humans. Indeed, considering the extent of genetic variability, even that focussed within the terminal phase of disease, one cannot help being daunted by the task of genetically dissecting RA in mixed human populations.

Second, the genetic influences revealed in the (B6 × NOD) combination studied here, summarized in Table , appear more tractable than in cases where arthritis was induced by immunization with collagen-, proteoglycan-, or oil-based irritants. Two loci clearly dominated, compared with the seven linked to inflammation in proteoglycan-induced arthritis 31, or the four determining CIA in the (DBA/1 × B10.Q) combination 10. The influence of the QTLs in our system also seems simpler. We did not detect separate influences on severity and kinetics, as had been reported previously for CIA 13. Undoubtedly, this great simplification results from the narrow focus of the K/B×N serum-transfer system, where genetic influences do not risk being masked by effects on immune responsiveness. Not surprisingly in this context, the present analysis did not reproduce the previously reported linkage peaks on mouse chr3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, and 16 for CIA, proteoglycan-induced arthritis, or Lyme arthritis 9 10 31. These might have influenced earlier steps in the arthritic process, reflect different underlying pathogenetic mechanisms, or be restricted to the strain combinations used in these studies, all different from (B6×NOD).

As in many previous studies, the highly susceptible parent strain in our analysis did not carry susceptible alleles at all loci. The B6 allele on chr1 dampened K/B×N serum-induced arthritis. This will no doubt prove a feature of human populations as well.

The C5 Locus.

The main genetic influence detected with the (B6 × NOD) strain pair maps to the C5 region of chr2, where the NOD-derived allele confers nonresponsiveness to K/B×N serum (absolute in homozygotes). A number of arguments support the assignment of this influence to the C5 gene, itself, known to be defective in the NOD strain 21. First, there was a perfect correlation between nonresponse and C5 deficiency in the panel of inbred strains (Table ). In addition, in the course of an in-depth analysis of the role of complement pathway components in the K/B×N model, we have found that C5 activity is essential for serum-transferred arthritis, completely prevented by treatment with an anti-C5 mAb or by a knockout mutation of the C5a receptor gene (unpublished data). Thus, the usual criteria for confirmation of the role of a candidate gene have been fulfilled: the presence of an inactivating mutation in deficient individuals, demonstration of a required biological role. Finally, implication of the C5 locus in a murine model of arthritis has precedents. Early evidence argued for an influence on CIA (reference 32, although such a linkage was later questioned [reference 33]); but more recent genetic data have confirmed the link 27 34 35, and CIA can be prevented by administration of anti-C5 mAb 26.

Our results significantly add to the story, showing that C5 acts at a late effector stage of arthritis and not necessarily in the immunological phase, as might have been extrapolated from the role of complement in B lymphocyte tolerance 36. Further, the data demonstrate a strong C5 gene-dosage effect. This suggests that the amounts of circulating C5 fraction may be limiting for the development of the arthritic lesion. It may prove valuable to routinely measure C5 levels and/or identify C5 genotypes in arthritis patients in order to stratify disease phenotypes or just to monitor disease progression.

The chr1 Region.

The other major genetic influence revealed by the (B6 × NOD) strain combination mapped to the distal region of chr1. Interestingly, this stretch also contains the Sle1 locus mapped by Wakeland's group 37 38, a locus that controls susceptibility to a systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease in mice. Apparent concordance between genetic intervals influencing different autoimmune diseases certainly has precedent 39 40. However, from a pathophysiological standpoint, the connection is not so obvious. sle1 controls the loss of tolerance to chromatin, while the effects we have mapped concern late-stage effector mechanisms. Thus, the colocalization may only be fortuitous. Alternatively, members of an immunologically relevant multigene family could be at the root, different members exerting divergent influences on the immune system processes underlying autoimmunity, or the convergence might reflect different consequences of the same genetic event, much as mutations affecting lytic properties of complement also influence complex organismal events such as B cell tolerance or lupus-like autoimmunity 36 41 42.

The data in Fig. 6 show that chr1's influence cannot be attributed to the fcgr2 gene, an otherwise attractive candidate because of its known alteration in the NOD strain 19, and previous implication in CIA 29. Given the above-discussed advantages of the K/B×N serum-transfer system, narrowing down the true support interval by congenic construction followed by recombinant analysis should be a fairly straightforward task.

In conclusion, the ready applicability of the K/B×N serum transfer model has allowed us to employ a diversity of inbred, congenic, and knockout mouse strains to analyze the genetics of end-stage phenomena in murine arthritis. One locus has been identified; positional cloning of the second should be fairly straightforward, particularly with the forthcoming availability of mouse genome sequence. Ultimately, this information, together with that from parallel analyses under way for other strain combinations, should greatly help in understanding aspects of human disease and deciphering its complex genetics.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Hergueux and S. Johnson for managing the colonies of K/B×N mice and provision of serum and to P. Michel, W. Manant, and M. Gendron for maintaining the mice.

H. Ji was supported by the Université Louis Pasteur, D. Gauguier by the Wellcome Foundation, K. Ohmura by the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and A. Gonzalez by the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. This work was supported by institute funds from the INSERM, the CNRS, the Hopital Universitaire de Strasbourg, and by grants from the Association pour la Recherche sur la Polyarthrite.

Note added in proof: Johansson et al. (2001. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1847–1856) reported the importance of the same chr1 and chr2 regions highlighted here in comtrolling susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis. Thus, the C5 and fcgr2 regions similarly control effector phase phenomena in different arthritis models.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: chr, chromosome; CIA, collagen-induced arthritis; QT, quantitative trait; QTL, QT locus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

References

- Jirholt J., Lindquist A.-K.B., Holmdahl R. The genetics of rheumatoid arthritis and the need for animal models to find and understand the underlying genes. Arth. Res. 2001;3:87–97. doi: 10.1186/ar145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor A.J., Snieder H., Rigby A.S., Koskenvuo M., Kaprio J., Aho K., Silman A.J. Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arth. Rheum. 2000;43:30–37. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<30::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn A.H., Kwoh C.K., Venglish C.M., Aston C.E., Chakravarti A. Genetic epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;57:150–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis F., Faure S., Martinez M., Prud'homme J.F., Fritz P., Dib C., Alves H., Barrera P., de Vries N., Balsa A. New susceptibility locus for rheumatoid arthritis suggested by a genome-wide linkage study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10746–10750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa S., Hayashi S., Tsukamoto Y., Goko H., Kawasaki H., Wada T., Shimizu K., Yasuda N., Kamatani N., Takasugi K. Identification of the gene loci that predispose to rheumatoid arthritis. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:1891–1895. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.12.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers E.F., Longman R.E., Du Y., O'Hare A., Cannon G.W., Griffiths M.M., Wilder R.L. A genome scan localizes five non-MHC loci controlling collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:82–85. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulko P.S., Kawahito Y., Remmers E.F., Reese V.R., Wang J., Dracheva S.V., Ge L., Longman R.E., Shepard J.S., Cannon G.W. Identification of a new non-major histocompatibility complex genetic locus on chromosome 2 that controls disease severity in collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Arth. Rheum. 1998;41:2122–2131. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2122::AID-ART7>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dracheva S.V., Remmers E.F., Gulko P.S., Kawahito Y., Longman R.E., Reese V.R., Cannon G.W., Griffiths M.M., Wilder R.L. Identification of a new quantitative trait locus on chromosome 7 controlling disease severity of collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Immunogen. 1999;49:787–791. doi: 10.1007/s002510050552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirholt J., Cook A., Emahazion T., Sundvall M., Jansson L., Nordquist N., Pettersson U., Holmdahl R. Genetic linkage analysis of collagen-induced arthritis in the mouse. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:3321–3328. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3321::AID-IMMU3321>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.-T., Jirholt J., Svensson L., Sundvall M., Jansson L., Pettersson U., Holmdahl R. Identification of genes controlling collagen-induced arthritis in micestriking homology with susceptibility loci precisely identified in the rat. J. Immunol. 1999;2917–2921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorentzen J.C., Glaser A., Jacobsson L., Galli J., Fakhrai-rad H., Klareskog L., Luthman H. Identification of rat susceptibility loci for adjuvant-oil-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6383–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahito Y., Cannon G.W., Gulko P.S., Remmers E.F., Longman R.E., Reese V.R., Wang J., Griffiths M.M., Wilder R.L. Localization of quantitative trait loci regulating adjuvant-induced arthritis in ratsevidence for genetic factors common to multiple autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4411–4419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingsbo-Lundberg C., Nordquist N., Olofsson P., Sundvall M., Saxne T., Pettersson U., Holmdahl R. Genetic control of arthritis onset, severity and chronicity in a model for rheumatoid arthritis in rats. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:401–404. doi: 10.1038/3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigar N.D., Cabrera W.H.K., Araujo L.M.M., Ribeiro O.G., Ogata T.R.P., Siqueira M., Ibanez O.M., De Franco M. Pristane-induced arthritis in mice selected for maximal or minimal acute inflammatory reaction. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:431–437. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<431::AID-IMMU431>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouskoff V., Korganow A.-S., Duchatelle V., Degott C., Benoist C., Mathis D. Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoreactivity. Cell. 1996;87:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto I., Staub A., Benoist C., Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition a glycolytic enzyme. Science. 1999;286:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korganow A.-S., Ji H., Mangialaio S., Duchatelle V., Pelanda R., Martin T., Degott C., Kikutani H., Rajewsky K., Pasquali J.-P. From systemic T cell self-reactivity to organ-specific autoimmune disease via immunoglobulins. Immunity. 1999;10:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T., Ono M., Hikida M., Ohmori H., Ravetch J.V. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fcγ RII-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;379:346–349. doi: 10.1038/379346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan J.J., Monteiro R.C., Sautes C., Fluteau G., Eloy L., Fridman W.H., Bach J.F., Garchon H.J. Defective Fcγ RII gene expression in macrophages of NOD micegenetic linkage with up-regulation of IgG1 and IgG2b in serum. J. Immunol. 1996;157:4707–4716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetsel R.A., Fleischer D.T., Haviland D.L. Deficiency of the murine fifth complement component (c5). A 2-base pair gene deletion in a 5′-exon. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:2435–2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A.G., Cooke A. Complement lytic activity has no role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 1993;42:1574–1578. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornall R.J., Prins J.B., Todd J.A., Pressey A., Delavato N.H., Wicker L.S., Peterson L.B. Type 1 diabetes in mice is linked to the interleukin-1 receptor and Lsh/Ity/Bcg genes on chromosome 1. Nature. 1991;353:262–265. doi: 10.1038/353262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth P.M., Witort E., Hulett M.D., Bonnerot C., Even J., Fridman W.H., McKenzie I.F. Structure of the mouse β Fcγ receptor II gene. J. Immunol. 1991;146:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E., Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traitsguidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly K.F., Olson J.M. Overview of QTL mapping software and introduction to map manager QT. Mamm. Genome. 1999;10:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s003359900997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Rollins S.A., Madri J.A., Matis L.A. Anti-C5 monoclonal antibody therapy prevents collagen-induced arthritis and ameliorates established disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:8955–8959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Kristan J., Hao L., Lenkoski C.S., Shen Y., Matis L.A. A role for complement in antibody-mediated inflammationC5-deficient DBA/1 mice are resistant to collagen-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4340–4347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A., Katz J.D., Mattei M.G., Kikutani H., Benoist C., Mathis D. Genetic control of diabetes progression. Immunity. 1997;7:873–883. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa T., Kubo S., Yoshino T., Ujike A., Matsumura K., Ono M., Ravetch J.V., Takai T. Deletion of fcγ receptor IIB renders H-2(b) mice susceptible to collagen-induced arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:187–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmdahl R., Andersson M.E., Goldschmidt T.J., Jansson L., Karlsson M., Malmstrom V., Mo J. Collagen induced arthritis as an experimental model for rheumatoid arthritis. Immunogenetics, pathogenesis and autoimmunity. APMIS. 1989;97:575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto J.M., Cs-Szabo G., Gallagher J., Velins S., Mikecz K., Buzas E.I., Enders J.T., Li Y., Olsen B.R., Glant T.T. Identification of multiple loci linked to inflammation and autoantibody production by a genome scan of a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. Arth. Rheum. 1999;42:2524–2531. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199912)42:12<2524::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Anderson G.D., Luthra H.S., David C.S. Influence of complement C5 and V β T cell receptor mutations on susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J. Immunol. 1989;142:2237–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M., Goldschmidt T.J., Michaelsson E., Larsson A., Holmdahl R. T-cell receptor V β haplotype and complement component C5 play no significant role for the resistance to collagen-induced arthritis in the SWR mouse. Immunology. 1991;73:191–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooley P.H., Seibold J.R., Whalen J.D., Chapdelaine J.M. Pristane-induced arthritis. The immunologic and genetic features of an experimental murine model of autoimmune disease. Arth. Rheum. 1989;32:1022–1030. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori L., De Libero G. Genetic control of susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis in T cell receptor β-chain transgenic mice. Arth. Rheum. 1998;41:256–262. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199802)41:2<256::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodeus A.P., Goerg S., Shen L.-M., Pozdnyakova O.O., Chu L., Alicot E.M., Goodnow C.C., Carroll M.C. A critical role for complement in maintenance of self-tolerance. Immunity. 1998;9:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel L., Mohan C., Yu Y., Croker B.P., Tian N., Deng A., Wakeland E.K. Functional dissection of systemic lupus erythematosus using congenic mouse strains. J. Immunol. 1997;158:6019–6028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel L., Blenman K.R., Croker B.P., Wakeland E.K. The major murine systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility locus, Sle1, is a cluster of functionally related genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1787–1792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031336098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K.G., Simon R.M., Bailey-Wilson J.E., Freidlin B., Biddison W.E., McFarland H.F., Trent J.M. Clustering of non-major histocompatibility complex susceptibility candidate loci in human autoimmune diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:9979–9984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M.M., Encinas J.A., Remmers E.F., Kuchroo V.K., Wilder R.L. Mapping autoimmunity genes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999;11:689–700. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Garnier G., Circolo A., Wetsel R.A., Ruiz P., Holers V.M., Boackle S.A., Colten H.R., Gilkeson G.S. Modulation of renal disease in MRL/lpr mice genetically deficient in the alternative complement pathway factor B. J. Immunol. 2000;164:786–794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botto M., Dell'Agnola C., Bygrave A.E., Thompson E.M., Cook H.T., Petry F., Loos M., Pandolfi P.P., Walport M.J. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:56–59. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]