Abstract

Self-antigens expressed in extrathymic tissues such as the pancreas can be transported to draining lymph nodes and presented in a class I–restricted manner by bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting cells. Such cross-presentation of self-antigens leads to CD8+ T cell tolerance induction via deletion. In this report, we investigate the influence of CD4+ T cell help on this process. Small numbers of autoreactive OVA-specific CD8+ T cells were unable to cause diabetes when adoptively transferred into mice expressing ovalbumin in the pancreatic β cells. Coinjection of OVA-specific CD4+ helper T cells, however, led to diabetes in a large proportion of mice (68%), suggesting that provision of help favored induction of autoimmunity. Analysis of the fate of CD8+ T cells indicated that CD4+ T cell help impaired their deletion. These data indicate that control of such help is critical for the maintenance of CD8+ T cell tolerance induced by cross-presentation.

There is now considerable evidence that CD8+ T cell responses can be induced in vivo by professional APCs capable of MHC class I–restricted presentation of exogenous antigens (1–3). This mechanism is known as cross-presentation and was suggested to be instrumental in the immune response to pathogens that avoid professional APCs (2–4). However, if this pathway was only directed towards induction of immunity, cross-presentation of self-antigens to autoreactive CD8+ T cells would result in autoimmunity. Recently, in studies using transgenic mice that express a membrane-bound form of OVA under the control of the rat insulin promoter (RIP-mOVA), we have shown that this is not the case. RIP-mOVA mice express membrane-bound OVA in pancreatic islets, kidney proximal tubular cells, thymus and testis. In these mice, OVA was found to enter the class I presentation pathway of a bone marrow– derived cell population and then activate transgenic OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (OT-I cells) (3) in LNs draining the sites of antigen expression. Although this form of activation initially led to proliferation of OT-I cells, it ultimately caused their deletion (5). Thus, cross-presentation can remove autoreactive CD8+ T cells, and may tolerize the CD8+ T cell compartment to self-antigens. These studies, however, did not explain why cross-presentation of a self-antigen induced CD8+ T cell tolerance, whereas foreign antigens induced immunity (1–4, 6).

In numerous models, CD4+ T cell help has been shown to be important for the induction or maintenance of immune responses by CD8+ T cells (7–11), but such help is not always essential (12–14). CD4+ T cell help has also been shown to be important for avoiding CTL tolerance induction (15–17). In these reports, however, it was not known whether CD8+ T cells were activated by cross-presentation or by direct recognition of antigen. Thus, whether CD4+ T cell help can affect tolerance induced by cross-presentation has not been addressed. Recently, we demonstrated that cross-priming by foreign antigens requires CD4+ T cell help for induction of CTL immunity (6). In this study, we have investigated the influence of such help on the deletion of CD8+ T cells induced by cross-presentation of self-antigens.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice were bred and maintained at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research. OT-II (18), OT-I RAG-1 and RIP-mOVA transgenic mice (3) have been described. Bone marrow chimeras were generated as described (5).

Adoptive Transfer and Flow Cytometry.

Preparation and 5,6-carboxy-succinimidyl-fluoresceine-ester (CFSE)-labeling of OT-I and OT-II cells, as well as analysis on a FACScan® (Becton Dickinson and Co., Mountain View, CA) were carried out as described (3, 5, 19). The following mAbs were used for immunostaining: PE conjugated anti-CD8 (YTS 169.4) and anti-CD4 (YTS 191.1) from Caltag Labs. (San Francisco, CA); anti-Vα2 TCR (B20.1) and anti-Vβ5.1/2 TCR (MR9-4).

Immunohistology.

Frozen tissue sections were stained with anti-CD8 supernatant (53.6.72 hybridoma), anti-CD4 ascites (H129.19 hybridoma) or with anti-Vα2 supernatant (B20.1), followed by anti-rat Ig-horseradish peroxidase (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and DAB (Sigma) as described (20). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Results

High Numbers of OT-I Cells Induce Diabetes in RIP-mOVA Mice.

In previous studies, OT-I cells adoptively transferred into RIP-mOVA mice were shown to be activated by cross-presentation of OVA in the draining LNs of OVA-expressing tissues (3). When a relatively large number of OT-I cells (5 × 106) was transferred, autoimmune diabetes was observed within 5–8 d (5). To investigate the dose response for induction of autoimmunity, various numbers of OT-I cells were transferred into RIP-mOVA mice (Table 1). 5–10 × 106 OT-I cells caused 100% of mice to develop diabetes. 50% of the recipients became diabetic when 1 × 106 OT-I cells were transferred, and 0.25 × 106 cells failed to cause disease in any of 26 recipients. Nevertheless, even with small numbers of OT-I cells transferred, their activation and proliferation occurred in the draining LNs (data not shown).

Table 1.

Autoimmune Diabetes in RIP-mOVA Mice Depends on the Number of Adoptively Transferred OT-I Cells

| No. of OT-I cells transferred | No. mice diabetic/ total No. mice (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 × 106 | 3/3 | (100%) | ||

| 5 × 106 | 18/18 | (100%) | ||

| 2 × 106 | 9/10 | (90%) | ||

| 1 × 106 | 4/8 | (50%) | ||

| 0.5 × 106 | 1/12 | (8%) | ||

| 0.25 × 106 | 0/26 | (0%) | ||

| 0.10 × 106 | 0/7 | (0%) | ||

Various numbers of Vα2+ Vβ5+ CD8+ cells prepared from OT-I RAG−/− mice were injected i.v. into unirradiated RIP-mOVA mice between 6 and 8 wk of age. These recipients were monitored daily for glucosuria. Mice that did not develop diabetes were monitored for at least 25 d and 5 recipients of 0.25 × 106 OT-I cells for 210 d. These data have been accumulated over six experiments.

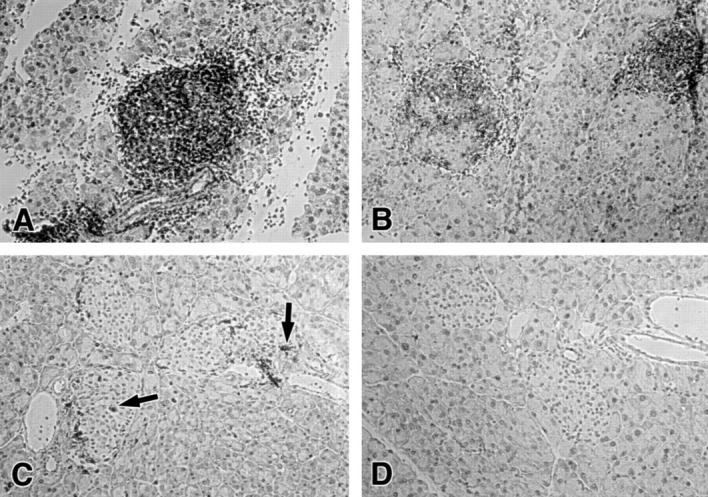

Histological examination revealed that on day 5 after adoptive transfer of 5 × 106 OT-I cells, the pancreatic islets of RIP-mOVA recipients were densely infiltrated with CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1 A) and with CD4+ T cells, B cells, and MAC-1–positive cells, which were of host origin (data not shown). Recipients of 1 × 106 OT-I cells that did not develop diabetes showed some CD8+ T cells within the islets on day 8 (Fig. 1 C), whereas recipients of less OT-I cells showed only sporadic islet infiltration (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Islet infiltration in RIP-mOVA recipients of OT-I and OT-II cells. The following numbers of OT-I and OT-II cells were adoptively transferred into unirradiated RIP-mOVA mice. (A) 5 × 106 OT-I cells; (B) 0.25 × 106 OT-I cells + 2 × 106 OT-II cells; (C) 1 × 106 OT-I cells; (D) 10 × 106 OT-II cells. Sections of the pancreas were stained 5 (A, B, and D) or 8 d (C) after adoptive transfer for CD8 (A–C) or CD4 (D). Arrows in C indicate infiltrating CD8+ cells.

Coinjection of OT-II Cells Can Induce Autoimmune Diabetes in RIP-mOVA Recipients of a Low Number of OT-I Cells.

Both the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments of RIP-mOVA mice were tolerant to OVA as measured by the ability to provide carrier-specific help (21), and to generate OVA-specific CTL (6), respectively (data not shown). This tolerance was most likely due to aberrant expression of mOVA in the thymus, as previously reported (3). Consequently, neither CD4+ nor CD8+ T cells specific for OVA were present in these mice prior to adoptive transfer.

To determine whether CD4+ T cell help could affect the response of OT-I cells, such help was provided by coinjection of CD4+ T cells from OT-II transgenic mice (OT-II cells), which produce H-2Ab–restricted T helper cells specific for OVA. When RIP-mOVA mice were coinjected with 2 × 106 OT-II CD4+ cells and a low number of OT-I CD8+ cells (0.25 × 106), approximately two-thirds of the recipients developed diabetes (Table 2). 5 d after adoptive transfer, islets were densely infiltrated by CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1 B). It is important to note that OT-II cells alone, even when injected at a higher dose (10 × 106 cells), were unable to cause islet infiltration (Fig. 1 D) or autoimmune diabetes (Table 2). Thus, the availability of CD4+ T cell help enhanced the response of OT-I cells, suggesting that such help may direct a normally tolerogenic CD8+ T cell response (with low doses of OT-I cells) towards autoimmunity, as measured by immunopathology.

Table 2.

Incidence of Diabetes after Cotransfer of OT-I and OT-II Cells

| No. cells transferred | No. mice diabetic/ total No. mice (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OT-I | OT-II | |||||

| 5 × 106 | − | 18/18 | (100%) | |||

| 0.25 × 106 | − | 0/26 | (0%) | |||

| 0.25 × 106 | 2 × 106 | 15/22 | (68%) | |||

| − | 2 × 106 | 0/12 | (0%) | |||

| − | 10 × 106 | 0/3 | (0%) | |||

0.25 × 106 OT-I cells were transferred either alone or together with 2 × 106 OT-II cells into sex matched RIP-mOVA mice of 6–8 wk of age. Coinjected recipients developed diabetes between day 6 and 10 after adoptive transfer and were sacrificed for histological verification of diabetes after a further 5–10 d. Mice which did not become diabetic were followed for 60–210 d. Shown are the results collected from 5 coinjection experiments with groups of 3–5 mice. The first two rows of this table were included from Table 1 for comparison.

CD4+ T Cell Help Prolongs the Lifespan of CD8+ T Cells Specific for Cross-presented Autoantigens.

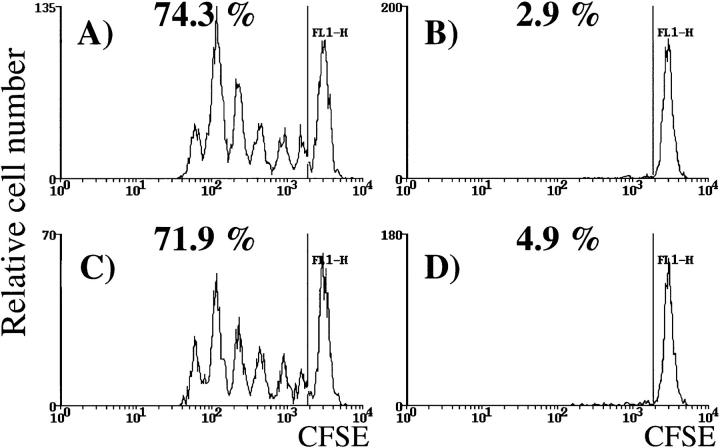

We then investigated whether OT-II cells achieved this effect by increasing the initial expansion of OT-I cells, or by impairing their deletion. To examine the first possibility, CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into RIP-mOVA mice in the presence or absence of coinjected OT-II cells. This technique enables monitoring of proliferation by detecting cells with 2n-fold reduced fluorescence intensity, where n is the number of cell cycles (5, 19). 2 d after adoptive transfer, we compared the CFSE fluorescence profiles of OT-I cells from the draining LNs of the kidney (Fig. 2) or pancreas (data not shown). 2 × 106 OT-II cells did not cause an obvious change in the proliferative peaks in these sites. No changes were observed with smaller numbers of CFSE-labeled OT-I cells (0.5 × 106), or at later time points (data not shown). These results suggested that the rate of OT-I cell cycling was not affected by OT-II cell help.

Figure 2.

OT-II cells do not enhance proliferation of OT-I cells in the draining LNs. 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into littermate RIP-mOVA mice alone (A and B) or together with 2.5 × 106 OT-II cells (C and D). After 52 h, lymphocytes from the renal (A and C) and inguinal (B and D) LNs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Profiles were gated on CFSE+ CD8+ cells. The numbers indicate the percentage of OT-I cells that had proliferated in vivo. These results are representative of five experiments.

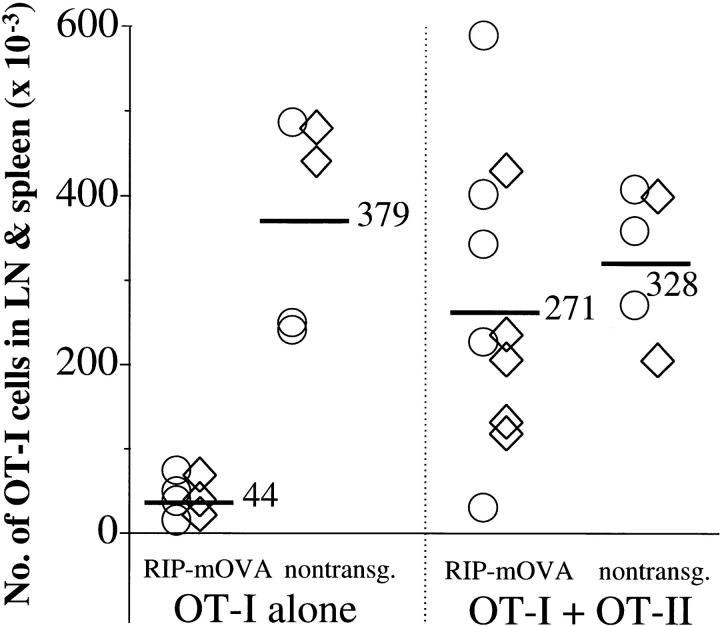

An alternative possibility was that CD4+ T cell help increased the survival of OT-I cells. To test this, it was necessary to generate chimeric mice that would not become diabetic when given OT-I cells. This could be achieved by back-crossing RIP-mOVA mice to the bm1 haplotype, which expresses the Kbm1 molecule instead of Kb and cannot present OVA to OT-I cells. By lethally irradiating and reconstituting these mice with B6 bone marrow, chimeric mice were generated that could present OVA on their bone marrow–derived cells, but not on peripheral tissues. These bone marrow chimeras were previously used to show that cross-presentation of self-antigen can lead to the deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells (5). To determine whether CD4+ T cell help could affect CD8+ T cell survival, these B6→ RIP-mOVA.bm1 chimeric mice and B6→ littermate.bm1 controls were injected with 5 × 106 OT-I cells either alone or together with 2 × 106 OT-II cells. After 6 wk, mice were sacrificed and the total number of OT-I cells in the spleen and LNs was assessed (Fig. 3). In 9 of 10 transgenic recipients of OT-II cells, this number clearly exceeded that in mice given OT-I cells alone, suggesting that CD4+ T cell help improved the survival of CD8+ T cells stimulated by cross-presentation. Islet infiltration or diabetes did not develop in B6→ RIP-mOVA.bm1 chimeric mice coinjected with OT-I and OT-II cells (data not shown) indicating that induction of diabetes was dependent on class I–restricted antigen recognition on islet β cells.

Figure 3.

OT-II cells impair the deletion of OT-I cells activated by cross-presentation. Bone marrow from B6 mice was grafted into irradiated RIP-mOVA.bm1 mice and nontransgenic littermates. 12 wk later, 5 × 106 OT-I cells ± 2 × 106 OT-II cells were adoptively transferred, and after 6 wk the number of Vα2+ Vβ5+ CD8+ cells in the LNs and spleen of the recipients was determined by flow cytometry. An average of 1.4% of CD8+ cells were Vα2+ Vβ5+ in uninjected mice. The total number of OT-I cells was derived using the formula: (%Vα2+ Vβ5+ cells in the CD8+ cells − 1.4%) × (%CD8+ T cells in live cells) × (number of live cells). The figure shows the results of two experiments (○, ⋄). The numbers and bars indicate the average number of OT-I cells in mice from both experiments. Injection of OT-II cells alone did not alter the proportion of host CD4− Vα2+ Vβ5+ cells.

Discussion

In this study, we have used the transgenic RIP-mOVA model to investigate the influence of CD4+ T cell help on the fate of autoreactive CD8+ T cells activated by cross-presentation of self-antigens. We have previously shown that naive OT-I cells, when adoptively transferred into RIP-mOVA mice, were activated by cross-presentation in LNs draining OVA-expressing tissues (3). After an initial expansion phase, this form of activation ultimately led to the deletion of OT-I cells (5), and may thus represent a mechanism that maintains CD8+ T cell tolerance to self. This conclusion highlighted the difference between cross-presentation of self versus foreign antigens, the latter generally inducing immunity (1–4, 6). Here, we demonstrate that OT-I cells activated by cross-presentation of self-antigens can induce islet β cell destruction. This could occur even in the absence of CD4+ T cell help, but only with a relatively large dose of OT-I cells (5 × 106). Transfer of such a high number of autoreactive CD8+ T cells allowed the initial wave of expansion to generate sufficient CTL to destroy all pancreatic β cells, before the CTL could be deleted. When the number of OT-I cells was lowered, they were deleted before inducing diabetes. Thus, when precursor frequencies are low, the dynamic process of proliferation versus deletion is biased towards the latter, particularly in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. Introduction of such help, provided by coinjecting OT-II cells, allowed low doses of OT-I cells to induce diabetes. This enhancing effect of OT-II cells was not exerted by increasing the proliferative rate of OT-I cells. Our results also argue against the interpretation that OT-I cells stimulated OT-II cells to destroy pancreatic β cells, because the induction of diabetes depended on MHC class I–restricted antigen recognition in islet cells, and because mouse islet β cells normally do not express MHC class II molecules (22). The mechanism supported by our findings is that CD4+ T cell help enhanced the survival of activated CD8+ T cells, allowing them more time to exert effector functions, possibly due to the induction of survival genes like bcl-xl. Thus, the balance between proliferation and deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells can be shifted towards an immunogenic response if CD4+ T cell help is available. This interpretation does not exclude other factors influencing this balance, such as inflammatory signals supplied by pathogens or material released from dying cells. In the present model, however, OT-II cells were able to shift the balance in favor of autoimmunity in the absence of any detectable inflammatory signals.

Previous studies investigating the influence of CD4+ T cell help on CTL tolerance have used foreign antigens. For example, responses to Qa1 and H-Y (16) were tolerogenic in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. Furthermore, survival of H-Y–specific transgenic T cells, which normally proliferate and then die in response to priming by male spleen cells, was increased by providing a stimulus for CD4+ T cells (17). This was consistent with our current observations, suggesting that CD4+ T cell help is not necessary for the initial proliferative response, but for the survival of subsequently produced CD8+ T cells. Perhaps, this also explains why CD8+ T cell immunity to many viral infections (11, 12, 14), but not CD8+ T cell memory (10, 11) can be induced in the absence of CD4+ T cell help.

The present study does not elucidate whether CD4+ T cell help was provided at the site of antigen-expression, e.g., in the pancreatic islets, or in the draining LNs. However, we have recently reported that generation of OVA-specific CTL by cross-priming, in another model, required cognate CD4+ T cell help (6). Thus, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells had to recognize antigen on the same APC in order to generate CTL immunity. In the present model it is not known whether cognate antigen recognition was required. If so, OT-II cells might influence the inductive phase of the autoreactive response by activating the cross-presenting APC such that it provided immunogenic rather than tolerogenic signals to CD8+ T cells. This may be mediated by signals like CD40-L, which induces the upregulation of costimulatory molecules such as B7 (23, 24) and the synthesis of IL-12 by the APC (25). Alternatively, CD4+ T cells may supply cytokines, such as IL-2, that enhance the expansion and/or survival of CD8+ T cells (17). Consistent with the view that CD4+ T cell help is required during priming, CD8+ T cell memory to H-Y persisted in the absence of CD4+ T cell help, provided such help was available during the initial priming phase (26).

The ability of antigen expressed on non-lymphoid tissues to cross-prime naive CD8+ T cells in the draining LNs might provide a plausible mechanism whereby infected cells and perhaps even malignant cells that lack the molecular machinery for direct immune induction, could prime CD8+ T cells (1–4). This, however, raises the question of how could CD8+ T cells distinguish between viral antigens expressed on virus-infected tissue cells, which they must kill, and self-antigens on normal tissue cells, which they must leave intact. As the availability of CD4+ T cell help appears to be responsible for dictating whether the CD8+ T cell response is immunogenic or tolerogenic, it is possible that the immune system controls autoreactive CD8+ T cells by limiting the availability of CD4+ T cell help (16). That is, in contrast to the situation with pathogens, the CD4+ T cell repertoire might normally be tolerized to self-antigens. Thus, CD4+ T-cell help would not be available for self-reactive CD8+ T cell responses, resulting in the deletion of this population. In the present model, the CD4+ T cell compartment was tolerant to OVA because of thymic negative selection. Future studies will address mechanisms of peripheral CD4+ tolerance to self-antigens that are not expressed in the thymus.

In conclusion, we have shown that, in the presence of CD4+ T cell help, CD8+ T cell deletion induced by cross-presentation of self-antigens is diminished, leading to autoimmunity. Thus, by limiting such help, the immune system can maintain peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance to self.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tatiana Banjanin, Jenny Falso, Maria Karvelas, Freda Karamalis, and Paula Nathan for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

C. Kurts is supported by a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft fellowship (grant Ku1063/1-2). This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant AI-29385 and grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council.

References

- 1.Bevan MJ. Antigen presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;182:639–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jondal M, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. MHC class I–restricted CTL responses to exogenous antigens. Immunity. 1996;5:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurts C, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Allison J, Miller JFAP, Kosaka H. Constitutive class I–restricted exogenous presentation of self antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:923–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rock KL. A new foreign policy: MHC class I molecules monitor the outside world. Immunol Today. 1996;17:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurts C, Kosaka H, Carbone FR, Miller JFAP, Heath WR. Class I–restricted cross-presentation of exogenous self antigens leads to deletion of autoreactive CD8+T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:239–245. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Miller JFAP, Heath WR. Induction of a CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4 help. J Exp Med. 1997;186:65–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keene JA, Forman J. Helper activity is required for the in vivo generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1982;155:768–782. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husmann LA, Bevan MJ. Cooperation between helper T cells and cytotoxic T lymphocyte precursors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1988;532:158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb36335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fearon ER, Pardoll DM, Itaya T, Golumbek P, Levitsky HI, Simons JW, Karasuyama H, Vogelstein B, Frost P. Interleukin-2 production by tumor cells bypasses T helper function in the generation of an antitumor response. Cell. 1990;60:397–403. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Herrath MG, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone MB, Whitton JL. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardin RD, Brooks JW, Sarawar SR, Doherty PC. Progressive loss of CD8+ T cell-mediated control of a γ-herpesvirus in the absence of CD4+T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:863–871. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler RM, Holmes KL, Hugin A, Frederickson TN, Morse H. Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo in the absence of CD4 helper cells. Nature. 1987;328:77–79. doi: 10.1038/328077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed R, Butler LD, Bhatti L. T4+T helper cell function in vivo: differential requirement for induction of antiviral cytotoxic T-cell and antibody responses. J Virol. 1988;62:2102–2106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2102-2106.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahemtulla A, Fung-Leung WP, Schilham MW, Kundig TM, Sambhara SR, Narendran A, Arabian A, Wakeham A, Paige CJ, Zinkernagel RM, et al. Normal development and function of CD8+cells but markedly decreased helper cell activity in mice lacking CD4. Nature. 1991;353:180–184. doi: 10.1038/353180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees MA, Rosenberg AS, Munitz TI, Singer A. In vivo induction of antigen-specific transplantation tolerance to Qa1a by exposure to alloantigen in the absence of T-cell help. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2765–2769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerder S, Matzinger P. A fail-safe mechanism for maintaining self-tolerance. J Exp Med. 1992;176:553–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirberg J, Bruno L, von Boehmer H. CD4+8− help prevents rapid deletion of CD8+cells after a transient response to antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1963–1967. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnden, M.J., J. Allison, W.R. Heath, and F.R. Carbone. 1998. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based α and β genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol. Cell Biol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison J, Campbell IL, Morahan G, Mandel TE, Harrison LC, Miller JF. Diabetes in transgenic mice resulting from over-expression of class I histocompatibility molecules in pancreatic beta cells. Nature. 1988;333:529–533. doi: 10.1038/333529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalor PA, Nossal GJ, Sanderson RD, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Functional and molecular characterization of single, (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl (NP)-specific, IgG1+B cells from antibody-secreting and memory B cell pathways in the C57BL/6 immune response to NP. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:3001–3011. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell IL, Oxbrow L, Koulmanda M, Harrison LC. IFN-γ induces islet cell MHC antigens and enhances autoimmune, streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the mouse. J Immunol. 1988;140:1111–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Wilson JM. CD40 ligand-dependent T cell activation: requirement of B7-CD28 signaling through CD40. Science. 1996;273:1862–1864. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grewal IS, Foellmer HG, Grewal KD, Xu J, Hardardottir F, Baron JL, Janeway C, Jr, Flavell RA. Requirement for CD40 ligand in costimulation induction, T cell activation, and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Science. 1996;273:1864–1867. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu U, Kiniwa M, Wu CY, Maliszewski C, Vezzio N, Hakimi J, Gately M, Delespesse G. Activated T cells induce interleukin-12 production by monocytes via CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. Long-lasting CD8 T cell memory in the absence of CD4 T cells or B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2153–2163. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]