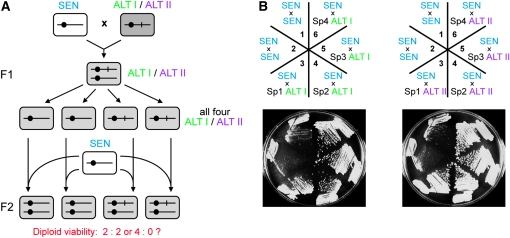

Figure 7.—

A non-Mendelian heritable change acts dominantly both to establish and to maintain the survivor state. (A) Schematic of the genetic analysis experiment (shown in B) addressing possible inheritance patterns for a hypothetical change that confers ALT telotypes. Because all four spores inherited the ALT telotype (see Figure 6), either the change in the original ALT cells is not a chromosomal mutation and therefore inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion (hypothesis 1) or it is a chromosomal mutation, which might be required not for the maintenance but for the establishment of the ALT telotype (hypothesis 2). The crosses of the spore progeny from F1 to SEN cells should distinguish between these two possibilities. If hypothesis 1 is correct, then all four spore progeny are expected to confer the ALT telotype to the diploids in F2. If the hypothetical change is a mutation that is required for the establishment of ALT, then two of the spore progeny that do not have the mutation will not rescue the senescence phenotype of SEN cells. (B, top) Diagram indicating the crosses examined. Cells in sectors 1 and 2 are positive controls for senescence obtained as described in Figure 5. Sectors 3–6 represent mating presurvivors (SEN) with four progeny spores from the same tetrad (from Figure 6). Each spore (Sp) colony was subsequently mated to another presurvivor, as shown. Plates from the second restreak are shown (∼40 generations after mating). Diploids were passaged for ∼80 generations, as in Figure 5. No viability crisis was observed for the diploids from sectors 3–6. One example each for tetrads derived from type I and type II survivors are shown; duplicate experiments gave similar results.