Abstract

An N-terminally truncated and cooperatively folded version (residues 6–39) of the human Pin1 WW domain (hPin1 WW hereafter) has served as an excellent model system for understanding triple-stranded β-sheet folding energetics. Here we report that the negatively charged N-terminal sequence (Met1-Ala-Asp-Glu-Glu5) previously deleted, and which is not conserved in highly homologous WW domain family members from yeast or certain fungi, significantly increases the stability of hPin1 WW (≈4 kJ mol−1 at 65°C), in the context of the 1–39 sequence based on equilibrium measurements. N-terminal truncations and mutations in conjunction with a double mutant cycle analysis and a recently published high-resolution X-ray structure of the hPin1 cis/trans-isomerase suggest that the increase in stability is due to an energetically favorable ionic interaction between the negatively charged side chains in the N terminus of full-length hPin1 WW and the positively charged ɛ-ammonium group of residue Lys13 in β-strand 1. Our data therefore suggest that the ionic interaction between Lys13 and the charged N terminus is the optimal solution for enhanced stability without compromising function, as ascertained by ligand binding studies. Kinetic laser temperature-jump relaxation studies reveal that this stabilizing interaction has not formed to a significant extent in the folding transition state at near physiological temperature, suggesting a differential contribution of the negatively charged N-terminal sequence to protein stability and folding rate. As neither the N-terminal sequence nor Lys13 are highly conserved among WW domains, our data further suggest that caution must be exercised when selecting domain boundaries for WW domains for structural, functional, or thermodynamic studies.

Keywords: WW domain, β-sheet, protein stability, double mutant cycle analysis, domain boundaries, laser temperature-jump relaxation

WW domains are naturally occurring protein–protein interaction modules of 30–50 residues, found in multidomain signaling and regulatory proteins (Sudol et al. 1995; Sudol 1996; Macias et al. 2000; Hu et al. 2004). Biophysical studies reveal that WW domains fold into their characteristic twisted three-stranded β-sheet architecture, and most (but not all) WW domains remain fully folded and functional when studied in isolation (Macias et al. 1996, 2000; Pires et al. 2001; Kowalski et al. 2002; Wiesner et al. 2002; Russ et al. 2005; Socolich et al. 2005; Petrovich et al. 2006).

The human cell regulatory protein hPin1 is a 167 residue two-domain protein, composed of an N-terminal WW domain (residues 1–39, hPin1 WW hereafter) and a C-terminal cis/trans-isomerase domain (residues 45–167). The domains are connected by a flexible linker (Ranganathan et al. 1997). Isolated hPin1 WW 6–39 has been studied extensively by us experimentally (Jäger et al. 2001, 2006; Deechongkit and Kelly 2002; Deechongkit et al. 2004, 2006; Nguyen et al. 2005; Powers et al. 2005) and others theoretically (Zhou 2003; Cheung et al. 2005; Cecconi et al. 2006). Its small size, high solubility (mM range) (Kowalski et al. 2002), aggregation resistance (M. Jäger and J.W. Kelly, unpubl.), ready availability by chemical synthesis (Kaul et al. 2001) or recombinant expression, and its simple two-state unfolding (Jäger et al. 2001, 2006) make it attractive as a model system to understand β-sheet folding energetics (Deechongkit et al. 2006). Moreover, it is amenable to extensive conventional side-chain mutagenesis as well as backbone amide mutagenesis (amide-to-ester or amide-to-E-olefin) enabling perturbations to be made to probe the basis for its stability and fast folding (microsecond timescale) (Jäger et al. 2001, 2006; Kaul et al. 2001; Deechongkit and Kelly 2002; Deechongkit et al. 2004, 2006; Nguyen et al. 2005).

Previous thermodynamic and kinetic studies on hPin1 WW were conducted with a sequence-minimized version (variant 5, Fig. 1B), which lacks the first five N-terminal residues (Met1-Ala-Asp-Glu-Glu5) (Jäger et al. 2001, 2006). These residues were not structurally defined in the first high-resolution X-ray structure of full-length hPin1, and were assumed to be disordered (Ranganathan et al. 1997). However, in a more recent X-ray structure of hPin1 (1.3 Å resolution), the negatively charged N-terminal Glu4 and Glu5 residues are structurally well defined and appear to be engaged in an ionic interaction with the positively charged ɛ-amino group of Lys13 in β-strand 1 (Fig. 1A; Verdecia et al. 2000). Lys13 is only weakly conserved among WW domain family members (more than 200 members). Position 13 residues with the highest frequencies (in parentheses) are Glu (0.32), Lys (0.15), Met (0.13), Arg (0.11), and Val (0.08). The N-terminal region is not conserved in the structurally and functionally related WW domains of the Pin1 cis/trans-isomerases from yeast or fungi (Fig. 1B, first three entries). To investigate the importance of ionic interactions between Glu4, Glu5, and Lys13 in the hPin1 WW ground and transition states, a detailed mutational study was conducted (Fig. 1B, variants 1–12).

Figure 1.

(A) Structural depiction of hPin1 WW (residues 1–39) generated using PDB-file 1F8A. The labeled side chains of residues Asp3, Glu4, Glu5, and Lys13 are shown in stick representation. (B) Sequence alignment of the hPin1 WW domain variants discussed in the main text. Residues that are part of the WW domain consensus sequence are shaded in gray. Residues that are engaged in the electrostatic interactions involving the N-terminal region and Lys13 within β-strand 1 are highlighted in blue. Residues that were mutated or deleted are color coded red. Residue numbering is based on variant 1.

Results and Discussion

Far- and near-UV CD spectra obtained with the isolated full-length hPin1 WW domain (residues 1–39, referred to as variant 1) and its N-terminally truncated version (residues 6–39, variant 5) were almost identical (data not shown), suggesting that deletion of the N terminus in variant 5 does not significantly perturb the structure of the WW domain. Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments on variant 1 (data not shown) and variant 5 (Kaul et al. 2001) reveal that both isolated domains remain monomeric up to a concentration of at least 200 μM.

Thermodynamic characterization

Normalized equilibrium unfolding curves of hPin1 WW variants 1 and 5, measured at low ionic strength (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0), are depicted in Figure 2A. Both variants unfold sigmoidally with very similar unfolding cooperativities, suggesting no significant changes in the solvent accessible area upon unfolding by the presence of the negatively charged N-terminal region. The midpoint of unfolding and the folding free energy of variant 1 (residues 1–39) significantly exceeds that of the N-terminally truncated variant 5 (see Table 1 for a summary of the thermodynamic data for variants 1–12). While deletion of the first two hydrophobic residues (Met-Ala) (variant 2) has no significant effect on WW domain stability (ΔΔG = 0.37 kJ mol−1 at 65°C), further deletion of the first negatively charged residue (Asp3, variant 3) leads to a significant destabilization by 1.40 kJ mol−1, relative to variant 1. Even further N-terminal truncation beyond Glu4 (variant 4) or Glu5 (variant 5) led to an additional destabilization of 1.18 kJ mol−1 (65°C) and 1.79 kJ mol−1 (65°C), respectively.

Figure 2.

Summary of thermodynamic and kinetic data. (A) Normalized equilibrium unfolding curves for hPin1 WW variant 1 (filled black circles) and variant 5 (open squares). (B) Double mutant cycle analysis to estimate the energetic contribution of the ionic interaction between the negatively charged N-terminal region and Lys13. The mutant cycle was calculated from thermodynamic parameters of variants 2, 6, 7, and 9 (see Table 1). Numbers indicate changes in free energy in kJ mol−1 upon mutation (ΔΔG = ΔG[i] – ΔG[j]) at 65°C with ΔG(i) and ΔG(j) representing the free energies of folding of reference (variant) state i and j, calculated from fitting of the temperature-induced equilibrium denaturation curves. Negative numbers indicate that the respective sequence manipulation is energetically destabilizing. (C) Summary of the kinetic analysis showing the dependence of the mutational ΦM-value, calculated from variants 1 and 2 (using variant 5 as reference) and the data in Tables 1 and 2, as a function of temperature. Solid black line: ΦM-value for variant 1. Dotted black line: ΦM-value for variant 2. Solid gray line: Average ΦM-value for variant 1 and 2. A ΦM-value = 0 indicates that the interaction is not formed in the transition state, while ΦM-value = 1 means that the interaction is fully formed. ΦM-values for both variants exhibit a similar temperature-dependence, although minor quantitative differences are detectable.

Table 1.

Summary of thermodynamic parameters

In order to ascertain whether the N-terminal electrostatic interaction can be diminished by increasing ionic strength, we recorded thermal denaturation curves for variants 1 and 5 in the presence of 500 mM sodium chloride. Our results (Table 1) reveal that the denaturation midpoint of variant 1 decreases from 69.2°C (no added NaCl) to 65.1°C in the presence of 500 mM NaCl (corresponding to a decrease in free energy (ΔΔG) of 1.64 kJ mol−1). In contrast, no significant salt-induced destabilization was observed for variant 5 (ΔΔG = 0.15 kJ mol−1), lacking the N-terminal electrostatic network. These data imply that the three charged residues in the N-terminal sequence contribute to the higher stability of variant 1, with Glu5 being the energetically most important residue, consistent with the interactions implied by X-ray crystallography (Verdecia et al. 2000). Electrostatic screening weakens this N-terminal electrostatic network in variant 1, consistent with its implied importance; however, the double mutant cycle analysis below was utilized to quantify this interaction.

Double mutant cycle analysis

To quantify the energetic contributions of the electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged N terminus and the positively charged Lys13 residue to the overall domain stability of hPin1 WW, a double mutant cycle analysis (Wells 1990; Horovitz 1996) was performed (Fig. 2B). Variant 2 was chosen as one of the four reference states, as the first two N-terminal residues in variant 1 contribute only minimally to domain stability and variant 2 retains all three N-terminal negatively charged residues. Replacing Asp3–Glu4–Glu5 with the nearly isosteric yet uncharged sequence Asn–Gln–Gln (variant 6) disrupts the electrostatic interactions between the N terminus and Lys13 and completely eliminates the stabilizing effect of the N-terminal region (ΔΔG = 4.22 kJ mol−1). A significant destabilization of variant 2 is also observed upon a Lys13Ala mutation in β-strand 1 (variant 7), which eliminates the positive charge of the Lys sidechain but retains the three negatively charged side chains in the N-terminal region. However, the decrease in stability in variant 7 (ΔΔG = 3.77 kJ mol−1) was slightly less than that observed in variant 6. A control experiment with the Lys13Ala mutation in the N-terminally truncated WW domain variant 5 (yielding variant 8) showed that the higher stability of variant 7 over variant 6 is in part due to a stabilizing effect of the Lys13Ala mutation on the stability of the three-stranded β-sheet substructure (ΔΔG = 0.53 kJ mol−1). Finally, simultaneous replacement of Asp3–Glu4–Glu5 and Lys13 with Asn–Gln–Gln and Ala, respectively, yields variant 9 (ΔΔG [65°C] = 3.81 kJ mol−1), which closes the double mutant cycle.

The coupling energy ΔΔG ionic is defined as ΔΔG ionic = ΔG (variant 9) − ΔG (variant 7) − ΔG(variant 6) + ΔG (variant2), with ΔG (variant i) equaling the free energy of folding of variant i obtained from a two-state analysis of the temperature equilibrium unfolding curves (Fig. 2B). At 65°C, a temperature at which accurate free energies for all mutants can be calculated from the experimental data without extrapolation beyond the unfolding transition region, a coupling energy of 4.18 kJ mol−1 was obtained. This value is similar to the free energy difference between variant 2 and 5 at the same temperature (ΔΔG = 4.00 kJ mol−1), indicating that the higher stability can mostly, but not entirely, be attributed to the (Asp3–Glu4–Glu5)–Lys13 ionic network.

The X-ray structure of hPin1 WW in the context of full-length hPin1 (Verdecia et al. 2000) provides strong experimental evidence for an electrostatic interaction between Lys13 and the negatively charged N terminus (in particular Glu5) in the crystalline state of hPin1 WW, and our thermodynamic data demonstrate that this interaction is energetically important. This ionic interaction is also observed in bovine and mouse Pin1 WW domains (sequence identical to hPin1 WW). In contrast, hPin1 WW homologs from yeast or fungi carry a Val residue (high β-sheet forming potential) instead of the charged Lys residue in β-strand 1, and the N-terminal residues are polar but not anionic (Fig. 1B). As expected from the high β-sheet propensity of Val, a Lys13Val mutation in the context of variant 5 (yielding variant 10) increases the stability of the hPin1 WW domain, but only slightly (ΔΔG [65°C] = 1.10 kJ mol−1) (Table 1). On the other hand, substitution of Lys13 with Tyr (variant 11), also a residue of high β-sheet propensity, was clearly less stable than variant 5 (ΔΔG [65°C] = 2.37 kJ mol−1), which might explain why Tyr is not found at this position among WW domains. Finally, replacing Lys13 with Glu, the statistically preferred residue at this position among WW-domain family members (frequency: 0.32), did not affect thermodynamic stability and resulted in a variant (variant 12) isoenergetic to variant 5.

Kinetic experiments

From the X-ray structure of the two-domain cell cycle regulatory protein hPin1 bound to its natural Pro-rich peptide ligand (Verdecia et al. 2000), and solution binding studies with isolated hPin1 WW variants 1 and 5 (Verdecia et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2006), it can be concluded that neither Lys13, nor the five N-terminal residues in hPin1 WW measurably contribute to ligand binding energy. Both Lys 13 and the N terminus are positioned on the concave side of the triple-stranded β-sheet, opposite to the convex side composing the ligand binding surface. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that interactions between Lys13 and the negatively charged N-terminal region coevolved in hPin1 WW domain to maximize the thermodynamic stability of the WW domain without compromising function, to the extent that binding energy is a surrogate for function.

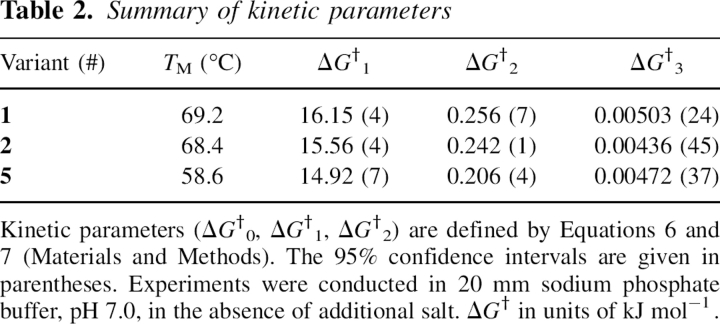

To test the influence of the charged N-terminal region on folding kinetics, laser temperature-jump relaxation experiments were conducted. As shown previously for variant 5 (Jäger et al. 2001, 2006; Nguyen et al. 2005), kinetic relaxation traces obtained with variant 1 and 2 could be fitted to a single exponential decay function (indicating barrier-limited two-state folding) over the entire temperature range investigated (45°C–70°C) (data not shown). A temperature-dependent ФM-analysis (Crane et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2001; Fersht and Sato 2004), calculated from the kinetic data in Table 2, reveals that at near physiological temperature, the contacts between Lys13 and the negatively charged N-terminal sequence that significantly stabilize the ground state of hPin1 WW, are only weakly developed in the folding transition state (ФM < 0.3). At higher temperatures, these interactions seem to increase slightly in magnitude, but never dominate transition state energetics.

Table 2.

Summary of kinetic parameters

Conclusions

We provide thermodynamic evidence that the negatively charged N-terminal sequence in hPin1 WW is engaged in a stabilizing ionic interaction with the ɛ-ammonium group of Lys13 comprising the β-sheet, as suggested by a recent X-ray structure of full-length hPin1 (Verdecia et al. 2000). Neither Lys13 nor the negatively charged N-terminal region seem to be directly involved in hPin1 WW function (binding of Pro-rich ligands). Likewise, Lys 13 and the N-terminal region are not conserved in structural and functional homologs of hPin1 WW. This finding reiterates previous observations that caution must be exercised when defining domain boundaries based on sequence alignments only. With regard to WW domains, a stabilizing effect of regions of low sequence conservation outside the consensus sequence of large domain family (more than 200 members identified to date), has also been observed previously for the human Yap65 WW domain (hYap65 WW). In hYap65 WW, the sidechain of Ile 7, which is positioned in an unstructured region N-terminal to residue Trp17 (the first residue of the three-stranded β-sheet substructure), is engaged in a hydrophobic contact with side chains within the β-sheet substructure and is required for a stable fold. N-terminal sequence truncation beyond the critical Ile7 residue leads to domain unfolding (Macias et al. 1996). Similarly, in dystrophin (a multidomain protein associated with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies), the WW domain makes extensive side-chain contacts with an α-helix preceding the N terminus of the triple-stranded β-sheet structure and two EF-hand domains downstream of the β-sheet. The isolated WW domain (lacking the N-terminal helix) showed no ligand-binding affinity and was presumed to be unfolded (Huang et al. 2000). These two examples suggest that the choice of domain boundaries can significantly affect the thermodynamic stability of WW domains, and that residues that lie outside the consensus sequence of this domain family must in some cases be included to assure maximal folding stability or avoid (partial) unfolding.

Fortunately, the truncated N-terminal residues in hPin1 WW variant 5 are neither crucial for its function (binding of a Pro-rich natural ligand) nor do they compromise the stability of the WW-domain fold substantially (Verdecia et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2006). Nevertheless, drastic sequence perturbations, such as classical Ala-truncations of residues that constitute the delocalized and highly conserved hydrophobic mini-core of hPin1 WW 6–39 (Trp11–Tyr24–Asn26–Pro37) or nontraditional backbone amide-to-ester substitutions to mutate buried backbone hydrogen bonds do result in partially unfolded or completely unfolded WW domains (Jäger et al. 2001; Deechongkit et al. 2004). In these instances, the higher thermodynamic stability offered by variants 1 and 2 may facilitate the extraction of accurate thermodynamic parameters in the case of these severe perturbations without the need to resort to stabilizing osmolytes (Deechongkit and Kelly 2002; Deechongkit et al. 2004).

Materials and Methods

WW domains were expressed recombinantly, and purified as described in detail elsewhere (Jäger et al. 2001). Equilibrium and kinetic experiments were performed in 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, in the absence of additional salt and in two cases in the presence of additional salt (500 mM sodium chloride). Equilibrium thermal stabilities of the WW domains were measured by far-UV CD (229 nm) in a 2-mm quartz cuvette. The temperature was raised from 0°C to 100°C in 2°C intervals. The protein solution was allowed to equilibrate for 60 sec at a preset temperature before the signal was averaged for 10 sec. Raw data were fitted to Equation 1, which assumes the validity of a two-state reaction:

In Equation 1, K eq = exp(−ΔG[T]/RT) is the equilibrium constant for folding, θ is the experimentally measured ellipticity, and θN(T) and θD(T) the slopes of the pre- and post-transitions. The folding free energy ΔG(T) was expressed as a parabolic Taylor's expansion around the midpoint of equilibrium folding (T = T M) (Equation 2):

Equilibrium unfolding transitions were normalized to the fraction of denatured protein (F D):

Kinetic experiments were performed as described in detail elsewhere (Jäger et al. 2001). Briefly, the shape f of each temperature-induced fluorescence decay curve (after t-jumps between 5° and 10°) was fit to a linear combination of the denatured decay (f D; after the new equilibrium is reached) and folded (F N, decay curve before the t-jump) shapes, in accord with a two-state behavior (Equation 4):

The change in fluorescence characterizing the phase transition from the native to denatured state was plotted as χ(t) (Equation 5):

Apparent rate constants k obs = k f + k uf were obtained by fitting χ(t) to a single exponential decay function. Microscopic folding and unfolding rates were calculated from k obs and K eq = k f/k uf, obtained from equilibrium unfolding experiments. Activation free energies (ΔG †) were determined by simultaneous fitting of the folding and unfolding rate constants to a Kramers model using a temperature-dependent free energy of activation (Equation 6):

where η(T) is the temperature-dependent solvent viscosity, T M is the midpoint of folding (ΔG[T M] = 0) and ν (ν = 50 nsec−1) is the viscosity-corrected frequency of the characteristic diffusional motion over the folding barrier that replaces the traditional Eyring-prefactor (≈100 fsec−1).

ΔG † in Equation 6 was expanded as a second-order polynomial around T M (Equation 7):

ΦM-values (a measure for the importance of a side-chain truncation/sequence truncation on transition state energetics) were calculated as described in detail elsewhere (Crane et al. 2000; Jäger et al. 2001).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the NIH (GM51105, to J.W.K.), the Skaggs Institute of Chemical Biology (J.W.K.), the Lita Annenberg Hazen Foundation (J.W.K.), and the NSF (MCB-0613643, to M.G.). M.J. thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Council, DFG) and the La Jolla Interfaces in Science program (supported by the Burroughs Welcome Fund) for postdoctoral fellowship support while this work was carried out. We also thank Prof. E. Powers (Scripps) for helpful discussions and Dr. Wim D'Haeze (Scripps) for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Jeffery W. Kelly, Department of Chemistry and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, BCC265, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA; e-mail: jkelly@scripps.edu; fax: (858) 784-9610.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.072775507.

References

- Cecconi F., Guardiani, C., and Livi, R. 2006. Testing simplified proteins models of the hPin1 WW domain. Biophys. J. 91: 694–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M.S., Klimov, D., and Thirumalai, D. 2005. Molecular crowding enhances native state stability and refolding rates of globular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102: 4753–4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J.C., Koepf, E.K., Kelly, J.W., and Gruebele, M. 2000. Mapping the transition state of the WW domain β-sheet. J. Mol. Biol. 298: 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deechongkit S. and Kelly, J.W. 2002. The effect of backbone cyclization on the thermodynamics of β-sheet unfolding: Stability optimization of the PIN WW domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124: 4980–4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deechongkit S., Nguyen, H., Jager, M., Powers, E.T., Gruebele, M., and Kelly, J.W. 2006. β-sheet folding mechanisms from perturbation energetics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16: 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deechongkit S., Nguyen, H., Powers, E.T., Dawson, P.E., Gruebele, M., and Kelly, J.W. 2004. Context-dependent contributions of backbone hydrogen bonding to β-sheet folding energetics. Nature 430: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A.R. and Sato, S. 2004. ϕ-value analysis and the nature of protein-folding transition states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 7976–7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz A. 1996. Double mutant cycles: A powerful tool for analyzing protein structure and function. Fold. Des. 1: R121–R126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Columbus, J., Zhang, Y., Wu, D., Lian, L., Yang, S., Goodwin, J., Luczak, C., Carter, M., Chen, L., et al. 2004. A map of WW domain family interactions. Proteomics 4: 643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Poy, F., Zhang, R., Joachimiak, A., Sudol, M., and Eck, M.J. 2000. Structure of a WW domain containing fragment of dystrophin in complex with β-dystroglycan. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 634–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger M., Nguyen, H., Crane, J.C., Kelly, J.W., and Gruebele, M. 2001. The folding mechanism of a β-sheet: The WW domain. J. Mol. Biol. 311: 373–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger M., Zhang, Y., Bieschke, J., Nguyen, H., Dendle, M., Bowman, M.E., Noel, J.P., Gruebele, M., and Kelly, J.W. 2006. Structure–function–folding relationship in a WW domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103: 10648–10653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul R., Angeles, A.R., Jager, J., Powers, E.T., and Kelly, J.W. 2001. Incorporating β-turns and a turn mimetic out of context in loop 1 of the WW domain affords cooperatively folded β-sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123: 5206–5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski J.A., Liu, K., and Kelly, J.W. 2002. NMR solution structure of the isolated Apo Pin1 WW domain: Comparison to the X-ray crystal structures of Pin1. Biopolymers 63: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias M.J., Hyvonen, M., Baraldi, E., Schultz, J., Sudol, M., Saraste, M., and Oschkinat, H. 1996. Structure of the WW domain of a kinase-associated protein complexed with a proline-rich peptide. Nature 382: 646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias M.J., Gervais, V., Civera, C., and Oschkinat, H. 2000. Structural analysis of WW domains and design of a WW prototype. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H., Jager, M., Kelly, J.W., and Gruebele, M. 2005. Engineering a β-sheet protein toward the folding speed limit. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109: 15182–15186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich M., Jonsson, A.L., Ferguson, N., Deggett, V., and Fersht, A.R. 2006. Phi-analysis at the experimental limits: Mechanism of β-hairpin formation. J. Mol. Biol. 360: 865–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires J.R., Taha-Nejad, F., Toepert, F., Ast, T., Hoffmuller, U., Schneider-Mergener, J., Kuhne, R., Marcias, M.J., and Oschkinat, H. 2001. Solution structures of the YAP65 WW domain and the variant L30 K in complex with the peptides GTPPPPYTVG, N-(n-octyl)-GPPPY and PLPPY and the application of peptide libraries reveal a minimal binding epitope. J. Mol. Biol. 314: 1147–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers E.T., Deechongkit, S., and Kelly, J.W. 2005. Backbone–backbone H-bonds make context-dependent contributions to protein folding kinetics and thermodynamics: Lessons from amide-to-ester mutations. Adv. Protein Chem. 72: 39–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R., Lu, K.P., Hunter, T., and Noel, J.P. 1997. Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell 89: 875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ W.P., Lowery, D.M., Mishra, P., Yaffe, M.B., and Ranganathan, R. 2005. Natural-like function in artificial WW domains. Nature 437: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolich M., Lockless, S.W., Russ, W.P., Lee, H., Gardner, K.H., and Ranganathan, R. 2005. Evolutionary information for specifying a protein fold. Nature 437: 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol M. 1996. Structure and function of the WW domain. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 65: 113–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudol M., Chen, H.I., Bougeret, C., Einbond, A., and Bork, P. 1995. Characterization of a novel protein-binding module—The WW domain. FEBS Lett. 369: 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecia M.A., Bowman, M.E., Lu, K.P., Hunter, T., and Noel, J.P. 2000. Structural basis for phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IV WW domains. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J.A. 1990. Additivity of mutational effects in proteins. Biochemistry 29: 8509–8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner S., Stier, G., Sattler, M., and Macias, M.J. 2002. Solution structure and ligand recognition of the WW domain pair of the yeast splicing factor Prp40. J. Mol. Biol. 324: 807–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.X. 2003. Effect of backbone cyclization on protein folding stability: Chain entropies of both the unfolded and the folded states are restricted. J. Mol. Biol. 332: 257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]