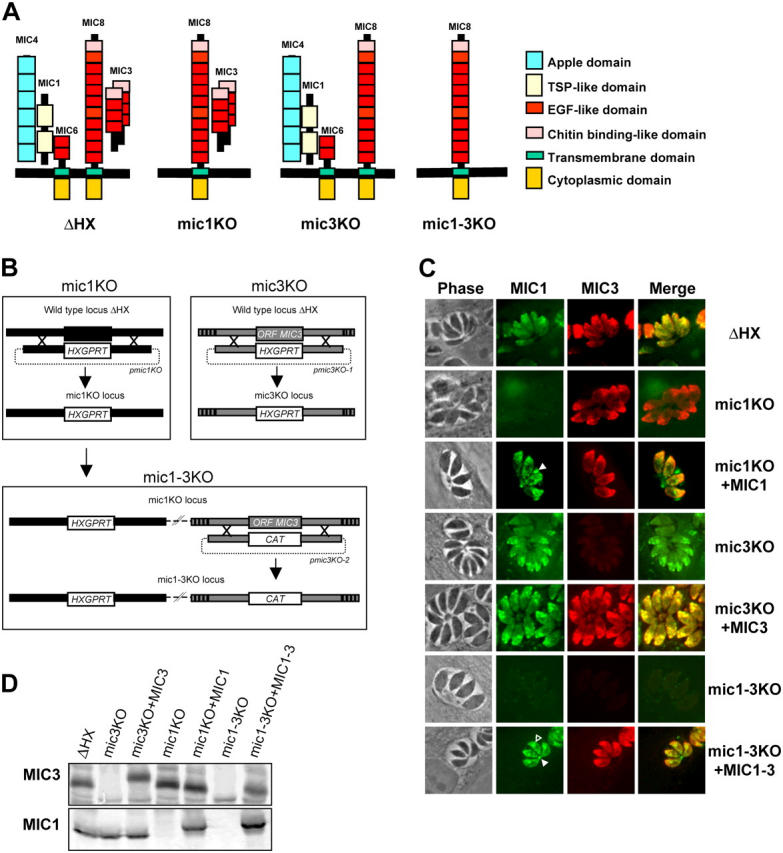

Figure 1.

Disruption of MIC1 and MIC3 genes and genetic complementation. (A) Schematic representations of the MIC1/4/6 and MIC3/8 complexes in micronemes of the ΔHX strain and the KO strains constructed in this study. In mic1KO (and mic 1-3KO), MIC1 is ablated, whereas MIC4 and MIC6 are mistargeted, resulting in a triple deletion of the proteins in micronemes. (B) Schematic drawing of the KO procedures described in Results. (C) IF of ΔHX (wild-type), MIC KOs, and complemented parasites. In wild-type, polyclonal anti-MIC3 (red) and mAb anti-MIC1 (green) show a punctuate fluorescence pattern within the apical complex, characteristic of microneme staining. Anti-MIC1 does not label mic1KO and mic1-3KO, whereas mic3KO and mic1-3KO do not react with anti-MIC3. Reexpression of MIC3 in mic3KO and mic1-3KO fully restored microneme labeling, whereas reexpression of MIC1 in mic1KO+MIC1 and in mic1-3KO+MIC1-3 led to some parasitophorous vacuole (closed arrowhead) and perinuclear (open arrowhead) labeling in addition to microneme staining. (D) Western blot analysis of MIC1 and MIC3 expression. On the top, the membrane was probed with anti-MIC3, and on the bottom, it was probed with anti-MIC1. The mobility shift observed for MIC3 in mic3KO+MIC3 is consistent with the addition of the Ty-1 epitope tag in this strain. Note the mobility shift of MIC1 in both complemented strains due to the addition of an myc epitope tag.