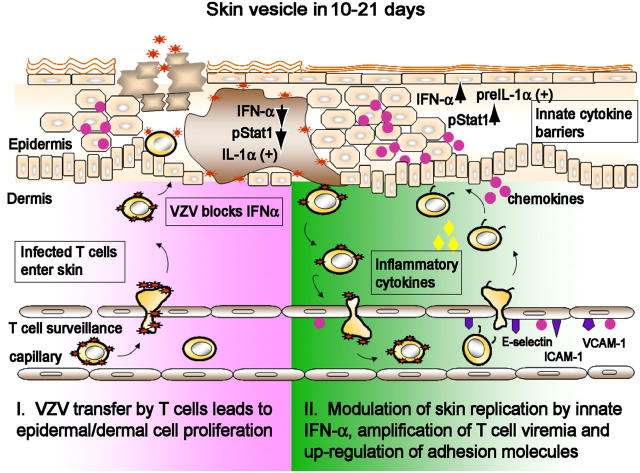

Figure 6.

A model of the pathogenesis of primary VZV infection. T cells within the local lymphoid tissue of the respiratory tract may become infected by transfer of VZV from its initial site of inoculation in respiratory epithelial cells. T cells may then transport the virus to the skin immediately and release infectious VZV. The remainder of the 10–21-d incubation period appears to be the interval required for VZV to overcome the innate IFN-α response in enough epidermal cells to create the typical vesicular lesions containing cell-free virus at the skin surface. The signaling of enhanced IFN-α production in adjacent skin cells may prevent a rapid, uncontrolled cell–cell spread of VZV. Secondary “crops” of varicella lesions may result when T cells traffic through early stage cutaneous lesions become infected and produce a secondary viremia. Intact host immune responses appear to be required to trigger up-regulation of adhesion molecules, facilitating the clearance of VZV by adaptive immunity.