Abstract

The amiloride-sensitive epithelial Nachannel (ENaC) is a heteromultimeric channel made of three αβγ subunits. The structures involved in the ion permeation pathway have only been partially identified, and the respective contributions of each subunit in the formation of the conduction pore has not yet been established. Using a site-directed mutagenesis approach, we have identified in a short segment preceding the second membrane-spanning domain (the pre-M2 segment) amino acid residues involved in ion permeation and critical for channel block by amiloride. Cys substitutions of Gly residues in β and γ subunits at position βG525 and γG537 increased the apparent inhibitory constant (K i) for amiloride by >1,000-fold and decreased channel unitary current without affecting ion selectivity. The corresponding mutation S583 to C in the α subunit increased amiloride K i by 20-fold, without changing channel conducting properties. Coexpression of these mutated αβγ subunits resulted in a nonconducting channel expressed at the cell surface. Finally, these Cys substitutions increased channel affinity for block by externalZn2+ ions, in particular the αS583C mutant showing a K i for Zn2+of 29 μM. Mutations of residues αW582L or βG522D also increased amiloride K i, the later mutation generating a Ca2+blocking site located 15% within the membrane electric field. These experiments provide strong evidence that αβγ ENaCs are pore-forming subunits involved in ion permeation through the channel. The pre-M2 segment of αβγ subunits may form a pore loop structure at the extracellular face of the channel, where amiloride binds within the channel lumen. We propose that amiloride interacts with Na+ions at an external Na+binding site preventing ion permeation through the channel pore.

Keywords: epithelial sodium channel, ENaC, amiloride, ion permeation, channel pore

introduction

The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) is a highly selective cation channel involved in the reabsorptive movement of Na+ions in epithelia of distal colon, airways, and distal nephron (Rossier et al., 1994). This electrogenic vectorial transport of Na+is accomplished by a two-step transport system involving the apical ENaC channel and the basolateral Na+-K+ pump. The functional characteristics of ENaC have been studied in isolated renal tubular segments using patch-clamp techniques and can be defined as a small 4–6 pS conductance channel in isotonic NaCl with high selectivity for Na+andLi+over K+ (<20:1) and slow gating kinetics. In addition, ENaC is highly sensitive to the diuretic amiloride with an apparent inhibitory constant of 10−7 M.

The primary structure of ENaC has been elucidated by expression cloning and is composed of three homologous αβγ subunits (Canessa et al., 1994b ). The ENaC subunits are members of a new gene superfamily of ion channels including a peptide-gated Na channel recently cloned in the snail Helix aspera, a voltage-insensitive brain Na channel showing high selectivity for Na+ions and amiloride sensitivity. More distant relatives of ENaC are gene products identified in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans called degenerins (MEC-4, DEG-1), whose functional properties are not yet known, but are thought to be involved in mechanosensation (Corey and García-Añoveros, 1996).

The predicted membrane topology of the ENaC subunits reveals two hydrophobic domains separated by a large hydrophilic loop that represents the major portion of the protein. Compelling evidences indicate the NH2 and COOH termini are facing the cytoplasmic side leaving the large hydrophilic loop in the extracellular milieu (Canessa et al., 1994a ; Renard et al., 1994; Snyder et al., 1994). This membrane topology makes ENaC resemble other channel types such as the inward-rectifier potassium channel, the ATP-gated cation channel (P2X receptor), or the mechanosensitive channel of Escherichia coli (North, 1996).

Expression of the αENaC subunit in Xenopus oocytes results in a small amiloride-sensitive current which is greatly potentiated by coexpression with the β and γ ENaC subunits (Canessa et al., 1994b ). Expression of β and γ subunits alone or together do not result in a detectable amiloride-sensitive current. These experiments suggest that the α subunit is a pore-forming subunit which contains all the biophysical and pharmacological properties of ENaC. Recent labeling experiments have shown that only the heteromultimeric αβγ channel can be detected at the cell surface indicating that the mature channel is a heteromultimeric channel made of three αβγ subunits with an unknown stoichiometry (Firsov et al., 1996). The functional role of the β and γ subunits has not yet been clearly established. From their structural homology with the α subunit, it is conceivable that the β or γ subunits also participate in the formation of the channel pore. Alternatively, the ion conduction pathway could be made exclusively of α subunits with the β and γ subunits representing accessory subunits that modulate ENaC activity.

To address these questions about the subunit structure of ENaC, we have used a site-directed mutagenesis approach to identify amino acid residues in the α, β, and γ subunits that play a role in ion permeation or channel sensitivity to amiloride block. In addition, we have performed different type of amino acid substitutions such as sulfhydryl or carboxylate residues with the purpose of engineering divalent cation binding sites for Zn2+or Ca2+ions that would block the channel. Within a short segment preceding the second membrane-spanning domain we have identified Gly and Ser residues in all three αβγ subunits, which when mutated alter the conducting properties, channel's affinity for amiloride, or create binding sites for blocking cations. These mutagenesis experiments support the notion that the amiloride binding site is located within the ion permeation pathway and that all three channel subunits participate in the formation of the conducting pore.

materials and methods

Preparation of the ENaC mutants

Rat ENaC channel cDNA encoding the αβγ subunits cloned into the pSD5 (α and β subunits) or pSport (γ subunit) vectors were used for site-directed mutagenesis. Mutations were introduced by PCR using a three-step protocol as described previously (Schild et al., 1996). The first PCR step used a 5′ mutagenic primer and a 3′ inverse hybrid primer carrying an unrelated sequence. The PCR product was elongated during the second step, and finally the cDNA was selectively amplified using a primer that primes synthesis only from DNA containing the unrelated sequence introduced in step 1. The final PCR product containing the desired mutation flanked by two unique restriction sites allowed its isolation and ligation into the ENaC cDNA. Mutations in the α subunit were introduced in a cDNA cassette flanked by unique Sfu1 and BamH1 restriction sites, mutations in the β subunit in a cassette flanked by Sac1 and Spe sites, and a cassette delineated by unique BglII and Apa 1 was used for γ mutations. cDNA sequencing confirmed the presence of the desired mutation.

In addition, the βG525 to C,D and γG537 to C mutations were respectively introduced in β and γ subunit cDNA containing a FLAG reporter octapeptide DYKDDDDK located ∼30 residues downstream the first transmembrane domain which can be recognized by anti-FLAG M2 IgG1 mouse monoclonal antibodies (Firsov et al., 1996). Introduction of the FLAG epitope does not alter the functional properties of the ENaC subunits and allows quantification of ENaC channel subunits expressed at the cell surface using a specific binding assay (Firsov et al., 1996).

Expression of ENaC Channels in Xenopus Oocytes

Complementary RNAs of each αβγ ENaC subunits were synthetized in vitro, and equal amount of subunit cRNA at saturating concentrations for maximal channel expression (5 ng total cRNA) were injected into stage V oocytes (Schild et al., 1995). Electrophysiological measurements were performed 24 h after injection.

Macroscopic whole-oocyte Li+currents (ILi) resulting from ENaC channel expression were measured using the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique and determined as the amiloride-sensitive inward current at −100 mV holding potential generated by substitution of 20 mM KCl with 20 mM LiCl in the external sucrose buffer solution.

Single channel recordings were obtained using patch-clamp technique in the cell-attached configuration. Data were sampled at 2 kHz and filtered at 100 Hz for analysis. Construction of current-voltage curves (I-V curves) for the channel open states was done from amplitude histograms containing at least 50 current transitions between open and closed states. All electrophysiological measurement were performed at room temperature.

Surface expression of ENaC channels was determined by specific binding of [125I]M2IgG1 (M2Ab) to oocytes expressing FLAG-tagged channel β and γ subunits as described previously (Firsov et al., 1996). The equilibrium dissociation constant of specific [125I]M2IgG1 (M2Ab) binding was 3 nM. Accordingly, 12 nM M2Ab were added to a Modified Barth's Saline (MBS) solution supplemented with 5% calf serum incubating the oocytes. After 1 h incubation at 4°C, oocytes were washed eight times with 1 ml MBS solution and transferred individually in a γ counter, and then used to measure amiloride-sensitive Li+ current. M2Ab nonspecific binding was detected with oocytes injected with ENaC cRNAs encoding nontagged subunits.

Solutions

Oocytes were incubated in a MBS solution containing in mM: NaCl 85; KCl 1; NaHC03 2.4; MgSO4 0.82; CaCl2 0.4; HEPES-NaOH 16, pH 7.2. Measurement of macroscopic currents were performed in sucrose buffer solutions containing in mM: either KCl, 20 or LiCl, 20 or NaCl, 20; sucrose, 150; CaCl2, 0.2; HEPES-KOH, 30, pH 7.2.

The pipette filling solution in patch-clamp experiments contained in mM: NaCl or LiCl, 110 mM; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 1.8; HEPES-OH, 10, pH 7.2. The bathing solution in these experiments was identical to the pipette solution except that 100 mM KCl replaced LiCl or NaCl.

Analysis of the Data

To analyze titration curves for inhibition of macroscopic Li+current (ILi), the ratio ILi/ILi0 measured in the presence (ILi) of a particular blocker B to that in the absence of the blocker (ILi0) is described by a Langmuir inhibition isotherm:

|

1 |

where K i is the inhibitory constant of the blocker, n′ is a pseudo-Hill coefficient.

In case of a voltage-dependent block, K i (V) is the voltage-dependent inhibitory constant, which has been expressed by Woodhull (Woodhull, 1973) as a Boltzmann relationship with respect to the voltage,

|

2 |

where K i(0) is the inhibitory constant at 0 mV, z′ is a slope parameter, and F, V, R, and T have their usual meanings. z′ is equal to the product of the actual valence of the blocking ion z and the fraction of the membrane potential (or electrical distance) δ acting on the ion.

results

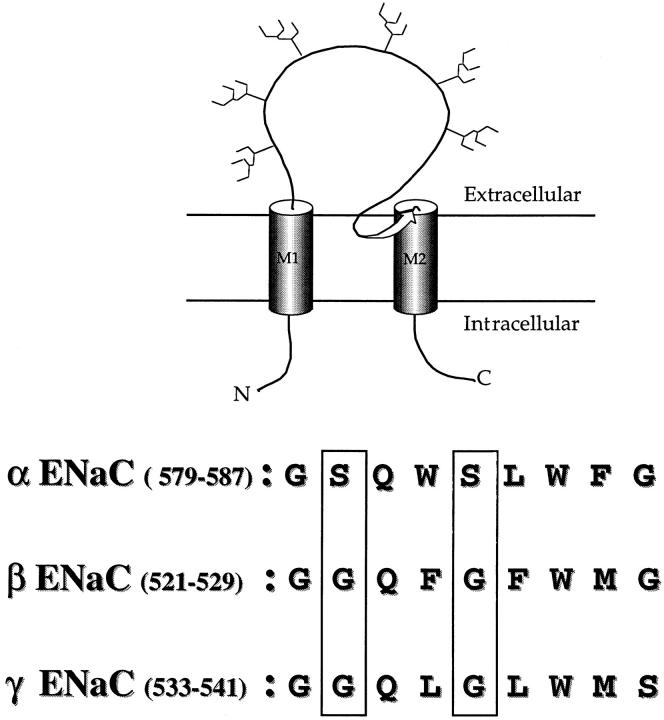

ENaC channel subunits are comprised of two hydrophobic segments M1 and M2 that probably form transmembrane α helices (Fig.1). Preceding the second transmembrane domain a short segment (pre-M2 segment) shows a high degree of homology among all the members of the ENaC gene family identified in epithelia or in CNS that exhibit sensitivity to amiloride block. It has been postulated that this segment forms an αβ barrel structure extending to the extracellular entrance of the channel pore (Guy and Durell, 1995). Sequence alignment of the pre-M2 segment in the αβγ ENaC subunits is shown in Fig. 1. This stretch of amino acid residues is strictly identical among the different αβγ ENaC genes from Xenopus laevis, rat, or human. To investigate the relationship of this amino acid segment with the channel pore, we specifically mutated the Ser residues (shown in the boxes) at positions S580 and S583 in the α subunits and the Gly residues at corresponding positions in the β (G522, G525) and γ (G534, G537) subunits. The functional consequences of these site specific mutations on the ionic permeation properties, and on the blocking pharmacology of the channel were investigated.

Figure 1.

Linear model of an ENaC subunit showing two transmembrane domains M1 and M2 with a pre-M2 segment (arrow) dipping into the membrane. The pre-M2 segment corresponds to the H2 segment in the linear model of ENaC subunits proposed by Canessa et al. (1994b). Sequence alignment of the pre-M2 segments of ENaC αβγ subunits is shown below. These sequences are identical in X. Laevis, rat, and human ENaC genes. Numbering refers to the ENaC rat sequence.

Amino Acid Substitutions in the αS583, βG525, γG537 Positions

Effects on ion permeation.

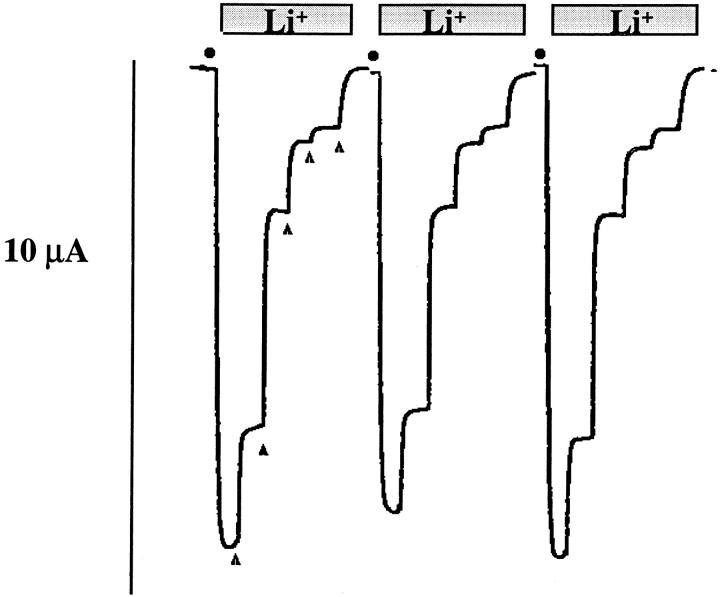

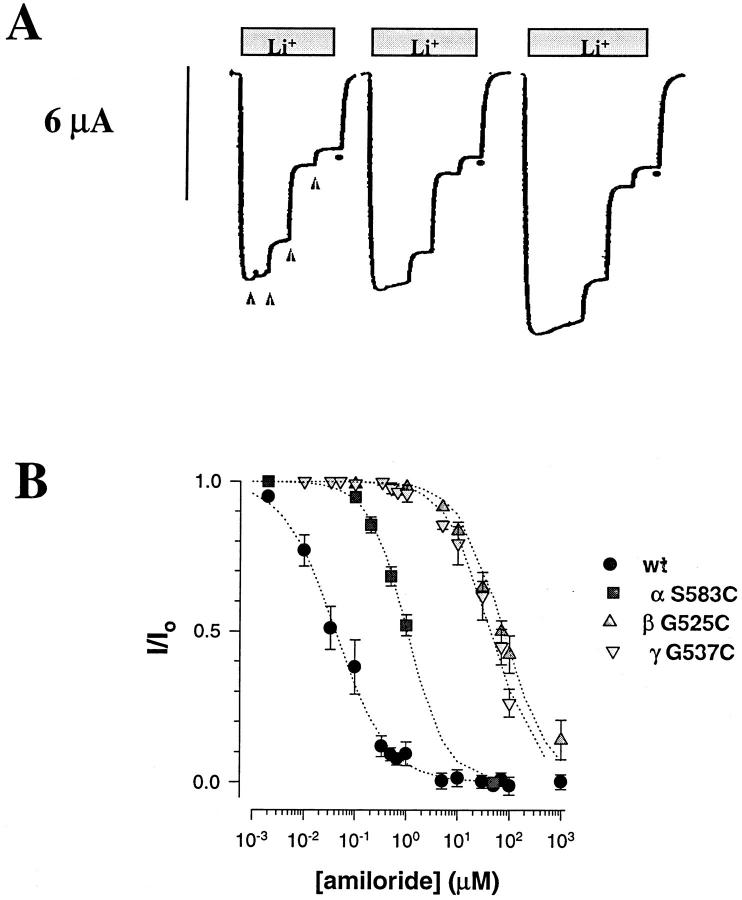

Among the unique functional characteristics of ENaC are its higher ionic permeability for Li+than Na+ ions, and its unmeasurably low permeability for K+ ions (Canessa et al., 1994b ). We have taken advantage of this ionic permeability property to assess functional expression of ENaC at the cell surface by measuring the inward current after substitution of 20 mM K+ by 20 mM Li+in a K-sucrose buffer solution. Fig. 2 shows representative recordings of macroscopic Li+currents (ILi) obtained with expression of αβγ wild-type (wt) 1 ENaC in Xenopus oocytes. Substitution of external K+ by Li+induced an inward current that was inhibited by increasing concentrations of external amiloride. Under these experimental conditions >98% of ILiwas inhibited by 5 μM amiloride, indicating that the amiloride-sensitive inward Li+current reflects channel activity of amiloride-sensitive ENaC expressed at the cell surface.

Figure 2.

Representative tracings of macroscopic inward Li+current recorded in three different oocytes expressing wild-type ENaC αβγ subunits. Substitution of 20 mM KCl with 20 mM LiCl in the external sucrose buffer medium (•) induced an inward Li+current that was inhibited by addition of 10 nM, 100 nM, 330 nM, 660 nM, 5 μM indicated by the filled triangles (▴).

Single amino acid substitutions of either αS583, βG525, or γG537 induced a robust inward Li+current in the μA range (Table I). With the exception of the βG525D, for which ILiwas <1 μA, the expressed current for the mutants were not different from the ENaC wild type. No ILicould be detected with coexpression of the Cys mutations in the three αβγ subunits (αG583C + βG525C + γG537C). The absence of ILiexpressed by the triple Cys mutant could result either from impaired channel expression at the cell surface or from a nonconducting channel.

Table I.

| αβγ ENaC channels | ILi + (μA) | n | Binding [125I]Ab | K i amiloride | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | fmols/oocyte (m ± SD) | μM | ||||||

| wild type | 11.5 ± 8.2 | 84 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.0 42 | ||||

| αS583C | 9.1 ± 8.3 | 20 | 1.0 | |||||

| αS583C + Zn2+ (0.2 mM) | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 12 | 5.7 | |||||

| βG525C | 7.4 ± 5.1 | 59 | 71.3 | |||||

| βG525A | 7.0 ± 5.5 | 14 | 131.0 | |||||

| βG525D | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 8 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | >100 | ||||

| γG537C | 19.0 ± 12.4 | 45 | 45.1 | |||||

| αS583C + βG525C | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 6 | 28.7 | |||||

| βG525C + γG537C | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 9 | >100 | |||||

| αS583C + βG525C + γG537C | 0 | 12 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | — | ||||

| αW582L | 5.5 ± 4.5 | 12 | 1.4 | |||||

| βF524A | 7.6 ± 4.4 | 9 | 0.0 39 | |||||

| βF524D | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 8 | 0.031 |

Effects of mutations in the pre-M2 segment of αβγ subunits on the expressed Li+ current, surface expression of the channel, and the inhibitory constant of amiloride (Ki). M2Ab denotes antibodies directed against the FLAG epitope in the β and γ subunits.

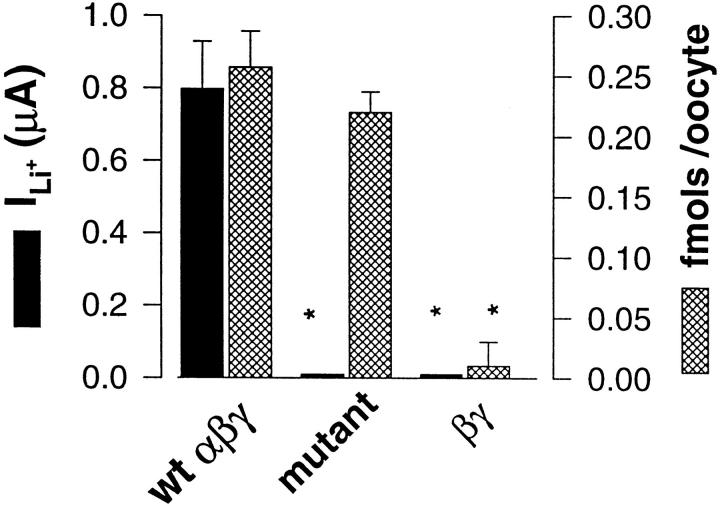

To address these possibilities, we measured cell-surface expression of the triple Cys mutant (αG583C + βG525C + γG537C) using a binding assay with a iodinated antibody (M2Ab) of high specific activity against a FLAG epitope placed in the extracellular domain of β and γ subunits. This epitope placed ∼30 amino acids downstream from the first transmembrane M1 domain does not affect ENaC channel function (Firsov et al., 1996). Fig. 3 compares ILiwith specific binding of M2Ab in oocytes expressing either FLAG-tagged αβγ ENaC wild type, the FLAG-tagged triple Cys mutant or FLAG-tagged βγ subunits. For the FLAG-tagged wt the mean ILicurrent expressed corresponded to ∼0.3 fmol of M2Ab specifically bound per oocyte at the cell surface. Surface expression of the triple Cys mutants was not statistically different from wild type as shown by M2Ab binding assay, but no detectable ILicould be measured. The absence of ILiand specific M2Ab binding in oocytes injected with only β and γ subunits tagged with the FLAG epitope demonstrate that single β, γ subunits or βγ dimers are not expressed at the cell surface, and that surface targeting of ENaC requires co-assembly of the three αβγ subunits. The specific M2Ab binding in oocytes with the triple Cys mutant implicates that the heterotrimeric channel mutant is correctly expressed at the membrane surface but is nonconducting. As shown in Table I, surface expression of the βG525D mutant was comparable to the wild type, and the lower ILifor this mutant is consistent with a lower ionic permeability.

Figure 3.

Cell surface expression and macroscopic ILiof wt ENaC (n = 39), triple Cys mutant (αSCβSCγSC) (n = 36) and βγ subunits (n = 41). Filled bars represents ILi. Hatched bars represents specific binding per oocyte of M2AB ([125I]M2IgG1) antibodies (fmols/oocyte) directed against a FLAG epitope introduced in the ectodomain of β and γ wt and mutant subunits. *Denotes statistical significance <0.001.

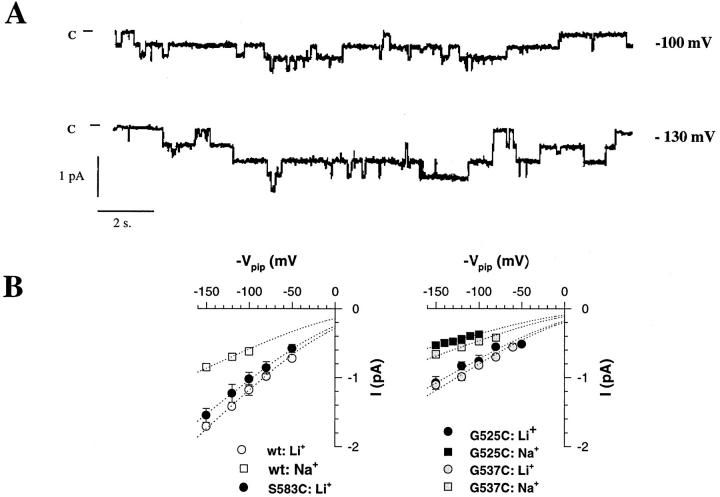

The consequences of Cys mutations of αS583, βG525, and γG537 residues on ion permeation were further investigated at the single channel level. Fig. 4 illustrates a single channel recording of the βG525C mutant coexpressed with the α and γ wt in the presence of external Na+as conducting ion. This mutant displays characteristic long opening and closing events as well as shorter transitions between open and closed states, a gating behavior similar to that described for the ENaC channel wt (Canessa et al., 1994b ; Palmer and Frindt, 1996). Changes in the single channel conductance are evidenced by the current-voltage relationships comparing wt ENaC, or αS583C mutant with βG525C and γG537C. The αS583 to C mutation did not significantly affect channel conductance (8.9 pS versus 10 pS for ENaC wt). The Cys mutations at corresponding positions in the β and γ subunits resulted in an ∼40% decrease in single channel cord conductance without affecting Na+over Li+permeability ratio. Channel conductance for Li+ions were 5.8 and 6.2 pS for βG525C and γG537C mutants.

Figure 4.

Effects of introducing Cys residues in pre M2 segment at positions αS583, βG525, and γG537. (A) Single channel tracings of βG525C mutant recorded with Na+as permeating ion. (B) Left: I-V relationships of wt ENaC and αS583C mutant. Cord conductance for wt ENaC (wt) in the presence of Na+was 5.1 and 10 pS with Li+. Li+conductance of αS583C was 8.9 pS. Right: I-V relationships for βG525C and γG537C. In the presence of Na+and Li+ions, cord conductances were, respectively, 3.2 and 5.8 pS for βG525C, 4 and 6.23 pS for γG534C. Dotted lines represent fit of the data of the I-V relationships according to the constant field equation. Each point represents mean value of two to five channels.

Taken together these results indicate that the Gly to Cys mutations in the β and γ subunits affect ion permeation through the channel without changing its Li+ over Na+ selectivity or its apparent gating properties. The effect of these mutations was additive and resulted in a nonconducting channel when all three subunits were mutated.

Channel block by amiloride and divalent cations.

In early experiments with expression of βG525C mutant together with α and γ subunits, it became rapidly evident that the inward Li+current was less sensitive to amiloride. Representative recordings of macroscopic ILifor the βG525C mutant and its dose-dependent inhibition by amiloride is illustrated in Fig. 5 A. ILiexpressed by G525C mutant could only be partially inhibited by increasing amiloride concentrations up to 100 μM, indicative of a decrease in amiloride sensitivity compared to wt ENaC (see Fig. 2). Amiloride titration curves of ILiis shown in Fig. 5 B for wt ENaC and the α, β, or γ or Cys mutants. In the presence of 20 mM external Li+, the inhibitory constant (K i) for amiloride block of wt ENaC was 42 nM. The αS583 to C mutation coexpressed with β and γ wt decreased channel affinity for amiloride block to 1 μM. A more dramatic decrease in affinity for amiloride was observed with the Gly to Cys mutations in the β and γ subunits with an ∼1,000-fold increase in amiloride K i. As shown on Table I similar amiloride resistance were conferred by the βG525 to A mutation, and the G525D mutant was completely resistant to amiloride block at concentrations up to 100 μM. Finally double Cys mutations in the α and β subunits were not additives with respect to amiloride sensitivity, whereas mutations in the β and γ subunits further increased the K i for amiloride. Thus Cys mutations in αβγ subunits affect external channel block by amiloride, but the effects of mutations in the β and γ are quantitatively more important and coincides with their respective decrease in single channel conductance.

Figure 5.

Amiloride sensitivity of αβγ Cys mutants. (A) Original tracings of amiloride inhibition of inward Li+current in oocytes expressing βG525C mutant together with α and γ subunits. Triangles (▴) represent addition of external amiloride at increasing concentrations of 0.1, 10, 70, and 100 μM, and • indicates return to the starting K solution. (B) Titration curve of Li+current by amiloride. I/I0 is the ratio of blocked over unblocked Li+current. Li+ current was measured in individual oocytes in the presence of four different amiloride concentrations (wt-ENaC, n = 82; αS583C, n = 27; βG525C, n = 59; γG537C, n = 14) Dotted lines represent fit of data to a Langmuir inhibition isotherm (see materials and methods).

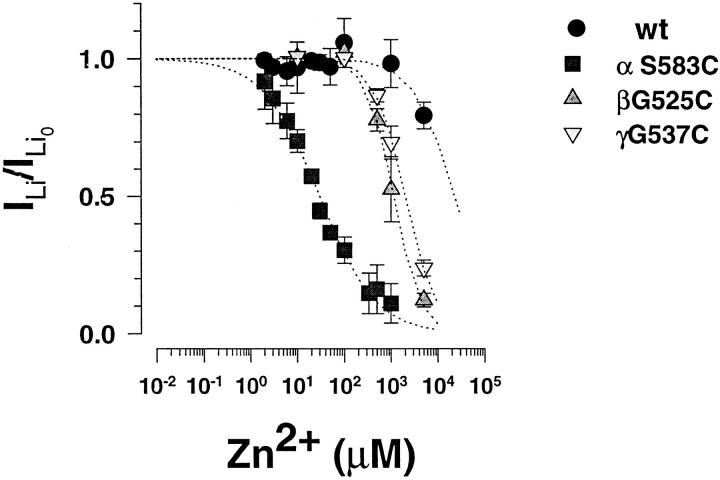

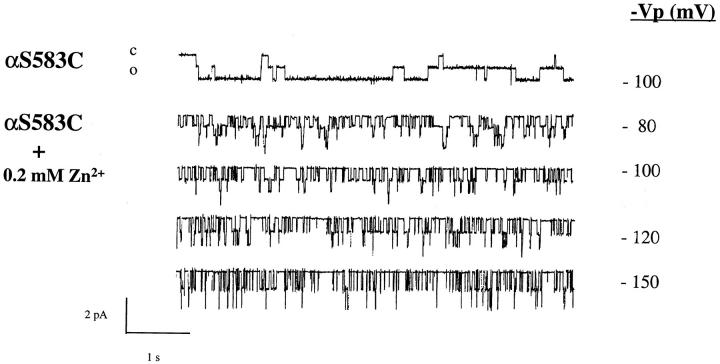

Introduction of Cys residues within the primary sequence of different channel types has been useful to confer sensitivity to channel block by divalent cations such as Cd2+ or Zn2+and to identify residues directly involved in the ionic permeation pathway (Favre et al., 1995; Chiamvimonvat et al., 1996). We tested the possibility that the Cys mutation makes ENaC channel sensitive to external block by Zn2+. Fig. 6 compares the ability of external Zn2+ to block the Li+current expressed by wt ENaC or Cys mutants. The wt ENaC is completely insensitive to external Zn2+ at concentrations up to the millimole (K ifor Zn2+ > 10 mM) whereas the αS583C mutants is blocked by μM concentrations of Zn2+ with a K i of 29 μM. The βG525C and γG537C displayed a significant block by Zn2+ compared to the wt, but with a 40- to 70-fold lower affinity for Zn2+ (K i = 1.1 and 1.9 mM, respectively) than the αS583C mutant. The Zn2+ block characteristics of S583C mutant at the single channel level is illustrated in Fig. 7. In the absence of external Zn2+, αS583C mutant shows long openings and closures; after addition of 0.2 mM Zn2+ the channel exhibit a flickery block characterized by short opening and closing events lasting <100 ms. Hyperpolarization of the membrane increased channel block, indicative of a slight voltage dependence for Zn2+ block. These experiments indicate that Zn2+ has access to the Cys residues at position αS583, βG525, γG537 in the αβγ subunits in order to block the channel, implicating that these residues are located in the ion permeation pathway. The voltage dependence of Zn2+ block suggests that αS583 residue is located within the transmembrane electric field.

Figure 6.

Block of wt ENaC and mutants by external Zn2+. Concentration dependence of Zn2+ inhibition of inward Li+current. I/I0represents the current ratio measured in the presence/absence of external Zn2+. Inhibitory constants (K i) were obtained from best fit of the data to a Langmuir inhibition isotherm (dotted lines). Zn2+ K i were >10 mM for wt ENaC (n = 34), 29 μM for αS583C (n = 42), 1.1 mM for βG525C (n = 10), and 1.9 mM for γG537C (n = 14).

Figure 7.

Single channel recording of αS583C mutant in absence or with 0.2 mM Zn2+in the external solution. In the presence of Zn2+ channel activity (n · P o) was 0.64 at −80 mV, 0.46 at −100 mV, 0.44 at −120 mV, and 0.35 at −150 mV.

Assuming that the residue at position 583 in the α subunit is a subsite of an external amiloride binding site, we tested the hypothesis that Zn2+ binding at Cys583 in the α subunit competitively interacts with amiloride at a common binding site. Dose-response curves of channel block by amiloride were performed in the presence of 0.2 mM external Zn2+. As shown in Table I, the αS583C mutant shows an approximately sixfold decrease in the affinity for amiloride block (K i = 5.7 μM) compared to the K i obtained in the absence of Zn2+ (K i= 1.04 μM). This shift in amiloride K i by Zn2+is strong evidence for a competitive interaction between Zn2+ and amiloride as predicted by the following equation relating amiloride K iin the presence (K app) or in absence of Zn2+ (K iamil):

|

3 |

where K iZn represents the K i for Zn2+ block. In the presence of 0.2 mM Zn2+, the theoretical K app value for amiloride was 8.1 μM, a value close to that determined experimentally in Table I. Our result suggest that Zn2+ competitively interacts with amiloride for channel block at a common binding site located within the ion conduction pathway.

Contribution of aromatic residues in amiloride sensitivity.

Amiloride is also a potent inhibitor of the Na+/H+ exchanger in which a stretch of amino acids including Phe residues (FFLF sequence) has been implicated in a putative amiloride binding site (Counillon et al., 1993). In addition, amiloride contains a guanidinium moiety and, interestingly, guanidinium toxins such as TTX or STX which block voltage-gated Na channels with high affinity, interact with aromatic residues at the entrance of the channel pore (Favre et al., 1995). We investigated the possible contribution of the aromatic Trp and Phe residues (αW582 and βF524) in ENaC block by amiloride. As shown in Table I, the W582L mutation decreased the channel affinity for amiloride block with a K i of 1.4 μM in the same range of that obtained with the αS583 to C mutation. By contrast the βF524A or D mutations adjacent to βG525 did not change channel affinity for amiloride.

Amino Acid Substitutions at αS580, βG522, γG534 Positions

Effects on ion permeation.

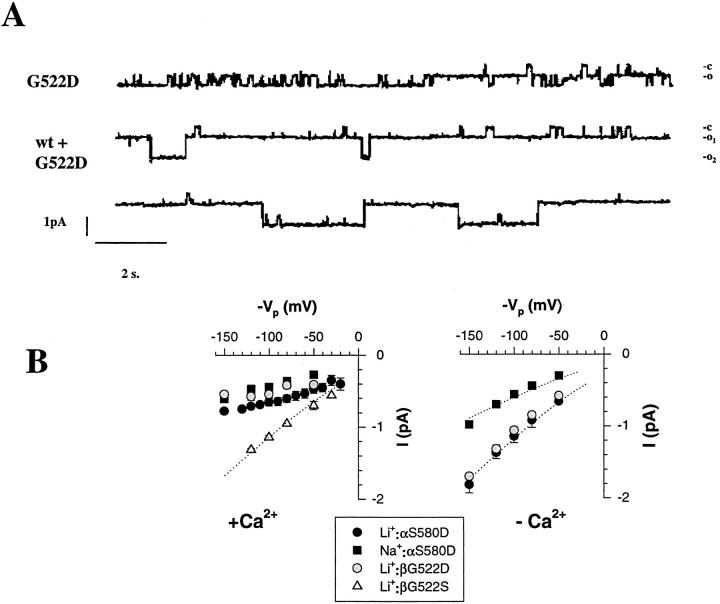

Asp or Glu substitution of the S and G residues at position αS580, βG522, γG534 did not significantly change the level of macroscopicILi(data not shown). However changes in single channel conductance were observed in single channel recordings as shown in Fig. 8 A. The βG522D mutant exhibits both long and short transitions between closed and open states with a reduced single channel conductance compared to ENaC wild type (upper tracing). This reduction in single channel conductance is particularly evident from the recording obtained in oocyte coexpressing both wt β and βG522D mutant together with α and γ subunits (lower tracings). In this tracing two channels with different conductances can be observed, the wt ENaC channel characterized by a larger conductance, and a channel of smaller conductance, the G522D mutant that spend most of the time in the open conformation. The I-V relationships in Fig. 8 B (left panel) shows a reduced single channel conductance for the αS580D and βG522D mutants in the presence of Na+or Li+ions compared to βG522S or wt ENaC (see Fig. 4 B). The I-V relationship for S580D and βG522D does not conform the predictions of the constant field equation as observed with the wt ENaC or the βG522S mutant, but rather suggests a voltage-dependent block of the channel. As shown in Fig. 8 B (right panel), removing external Ca2+from the pipette solution restored a single channel conductance of 11.5 pS with Li+and 6.7 pS with Na+for both mutant that was similar to wt ENaC or the G522S mutant. This Ca-dependent decrease in single channel conductance can be interpreted as a fast channel block which involves coordination of C a2+ ions with the negatively charged Asp− at position αS580 and βG522, whereas the βG522S mutant remains insensitive to Ca2+ block. The accessibility of the residues αS580 and βG522 by Ca2+ions and the resulting channel block further support the notion that the segment encompassing αS580 and βS583 residues are facing the pore lumen.

Figure 8.

Effects on single channel conductance of introducing negatively charged residues Asp in the pre-M2 segment of αβ subunits. (A) Upper tracing shows single channel recording in oocytes expressing α, βG522D, γ mutants. The lower tracings were recorded from an oocyte expressing both βG522D and β wild type together with α and γ subunits. Two channels with different conductances can be observed. (B) Left: I-V relationship of αS580D, βG522D, and βG522S in the presence of with 1.8 mM Ca2+ in the patch pipet. Cord Li+conductance was 9.6 pS for βG522S. Right: I-V relationship of S580D, G522D in the absence of Ca2+ in the pipet. Cord conductance were 6.7 and 11 pS for S580D in the presence of Na+and Li+respectively and 11 pS for βG522D with Li+ions. Each point represents a mean value of three to five channels.

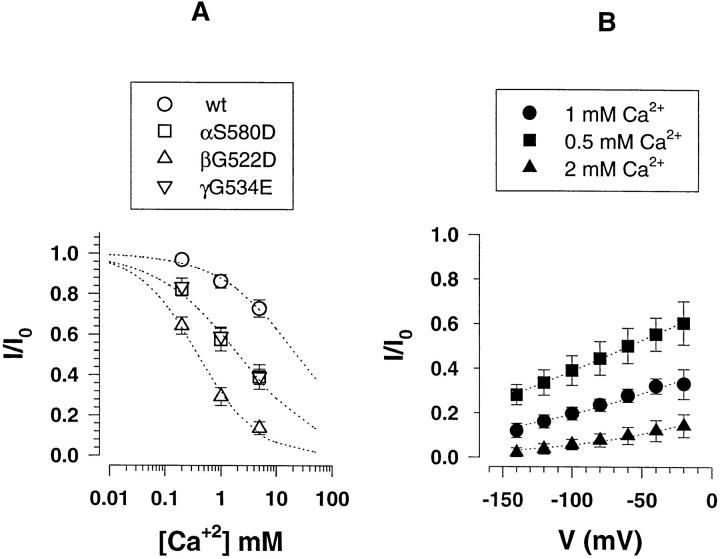

Equilibrium kinetics parameters of channel block by external Ca2+ were determined from Ca2+titration of macroscopic Li+currents shown in Fig. 9 A. The wt ENaC exhibits a low sensitivity to external Ca2+block, as it was previously shown for external Zn2+. The βG522D mutant was the most sensitive for Ca2+block among the mutants tested with a K i of 0.4 mM. The αS580D and γG534E shows similar affinities for Ca2+block with a K i around 2 mM. As suggested by the single channel I-V relation, block of βG522D mutant by external Ca2+ is voltage-dependent, and Fig. 9B shows the block of Li+current by Ca2+ as a function of the membrane potential. For different external Ca2+concentrations, hyperpolarization of membrane increased external Ca2+block as shown by a decrease in the Li+current. In order to obtain empirical parameters for the voltage dependence of Ca2+block, the data were fitted according to the Woodhull model (Woodhull, 1973). A mean slope parameter z′ for the voltage dependency of Ca2+block was 0.30 ± 0.03 for the three different experimental conditions. According to the Woodhull formalism, this slope parameter equals the valence of the blocking ion and the fraction of membrane potential acting on the ion at its blocking site. This fraction of the voltage drop sensed by Ca2+ions or the electrical distance was ∼15% of the transmembrane electric field, suggesting that Asp at position βG522 of the pre-M2 segment is located within the outer entrance of the channel pore.

Figure 9.

Block of αS580D, βG522D, γG534E mutants by external Ca2+. Mutant subunits were coexpressed with α, γ wild-type subunits. (A) Concentration dependence of inhibition of Li+current by external Ca2+. The ratio I/I0 represents the measured ILiin the presence/absence of external Ca2+ions. Ca2+ inhibitory constants (K i) obtained from fit to inhibition Langmuir isotherm (dotted lines) were 2.1 mM for the αS580D (n = 8), 0.4 mM for βG522D (n = 10), and 2.2 mM for γG534E (n = 8). (B) Voltage dependence of βG522D mutant block by external Ca2+ at concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 2 mM (n = 4). Dotted lines represent fit of the data to Eq. 2 (see materials and methods) gave K i(0) values of 0.67, 0.97, and 0.49, z′ values of 0.26, 0.28, and 0.35 for the experiments done with respectively 0.5, 1, and 2mM Ca2+.

Pharmacological properties.

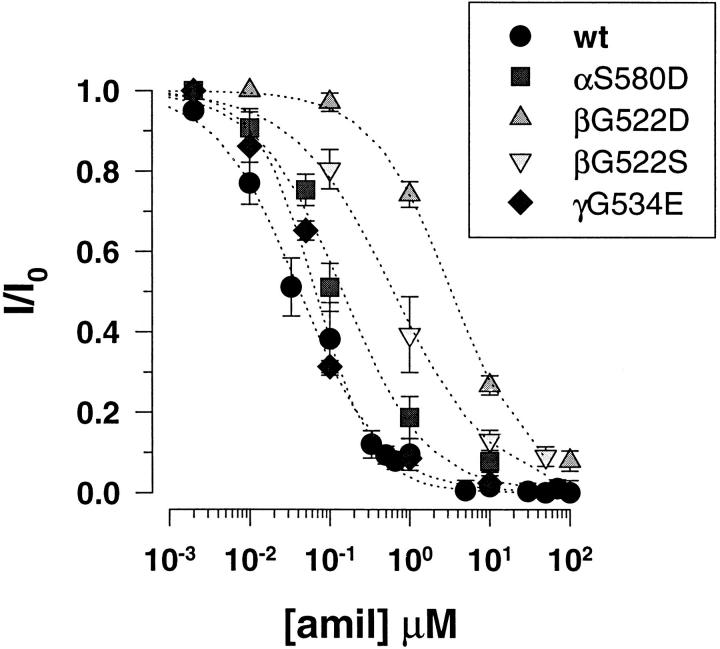

The αS580 to D and γG534 to E mutations did not significantly change the channel affinity for amiloride block as shown in Fig. 10. Mutations at the corresponding position in the β subunit resulted in decrease in amiloride sensitivity with K i for amiloride of 3.4 ± 0.4 and 0.63 ± 0.09 μM for the βG522D and βG522S mutants. Since these titration experiments were performed in the presence of external Ca2+(1.8 mM) the lower affinity of βG522D mutant for amiloride block compared to the βG522S mutant can account for a competitive interaction between Ca2+and amiloride at a common binding site. The consequences of these mutations on amiloride sensitivity were however less important than the mutations described previously and located three residues further downstream in the amino acid sequence.

Figure 10.

Decreased sensitivity of βG522D mutant to amiloride. Dose-dependent inhibition of Li+current by amiloride. Inhibitory constants (K i) obtained from fit of the data to inhibition Langmuir isotherm were 0.14 μM for αS580D (n = 12), 0.06 μM for γG534E (n = 8), 3.4 μM for βG522D (n = 16), and 0.6 μM for βG522S (n = 10).

discussion

Block by Amiloride

This study identifies residues in a short amino acid segment preceding the second transmembrane domain of αβγ subunits that when mutated decrease channel affinity for amiloride block. These amino acid residues have been identified in all three subunits at corresponding positions in a locus that comprises Ser residues in the α subunits and Gly in β and γ subunits. A more than 1,000-fold decrease in amiloride sensitivity resulted from substitutions of a Gly residue in the β and γ subunits, whereas mutation of the corresponding Ser residue in the α subunit resulted in a smaller (∼20-fold) change in the channel's affinity for amiloride block. These observations indicate that all three αβγ subunits of the heteromultimeric ENaC channel are involved in the channel block by amiloride. In addition, the three αβγ subunits likely display specific structural characteristics in their respective molecular binding interactions with amiloride and/or the modulation of this effect. The W582 mutation in the α subunit decreases K ifor amiloride but not the corresponding aromatic residue F524 in the β subunits. Conversely, mutations of the G522 in the β subunit changed amiloride K i but not the corresponding mutations in the α and γ subunits.

The observation that mutations of βG525 and γG537 in β and γ subunits have the most important effect on channel sensitivity to amiloride suggests that these residues are critical for the binding interaction between amiloride and its receptor on the channel. However expression of ENaC α subunit alone in Xenopus oocytes induces an amiloride-sensitive current of low magnitude (∼20 nA range) that exhibits a high affinity for amiloride of ∼100 nM, suggesting that this pharmacological property can be conferred to the channel by the α subunits alone (Canessa et al., 1994b ). It should be pointed out that there is presently no direct evidence that functional channels in oocytes expressing α subunits alone are exclusively made of α subunits, and therefore the contribution of other endogenous subunits in the formation of the channel cannot be ruled out. Thus the pharmacological profile of a homomultimeric channel made of α subunits still remains an open question. Among the recently cloned ENaC subunits, the δ subunit shows the highest degree of homology with the α subunits, and within the stretch of residues shown in Fig. 1, the δ subunit differs from the αENaC by a Leu at position 581 and Tyr at position 582, both subunits having a conserved Ser residue at position 583 (Waldmann et al., 1995a ). Similar to the α subunit, the δ subunit associates with β and γ subunits to form functional heteromultimeric channels at the cell surface. However, the δβγ channel differs from the αβγ channel by a 30 times higher K i for amiloride, which is in the same order of magnitude as those observed after mutations of αS583 and αW582 in the α subunit. The structural basis for this difference in amiloride sensitivity remains to be determined and could possibly involve the Trp to Tyr and Gln to Leu substitutions, although they represent rather conservative amino acid substitutions. Thus there is no doubt that the α subunit is important in determining the pharmacological properties of the channel, but the almost complete resistance to amiloride obtained with mutations in the β and γ subunits stresses the important contribution of both subunits in the binding interactions between channel and amiloride.

It may be too early to speculate on the molecular basis of the high affinity of ENaC for amiloride. Conserved Gly residues typically tend to play a structural role in folding of the peptide backbone, so the Gly mutations may change the structure in this region and consequently alter amiloride block. However the Zn2+ and Ca2+ block clearly show that these residues must be accessible to solution and the competitive interactions between amiloride and divalent cations are consistent with the notion that αS583, βG525 and γG534 form an external binding site for amiloride. These results do not exclude the possibility that other functional domains of ENaC subunits may be involved in binding interactions with amiloride. A study on structure activity relationships of amiloride and analogs has proposed that ENaC block by amiloride involves a two-step process with distinct binding sites on the channel molecule (Li et al., 1987). Based on sequence relationships among amiloride binding proteins, Kieber-Emmons et al. identified a EWYRFHY locus in the extracellular loop of ENaC as a candidate site for amiloride binding (Kieber-Emmons et al., 1995).

Block by Divalent Cations

Divalent cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, or Ba2+ block ENaC from the external side in a voltage dependent manner and with very low affinity (Palmer, 1985). In the toad urinary bladder the estimated K i for these divalent cations exceeds 200 mM. Introduction of negatively charged residues at position αS580, βG522, or γG534 increased the channel's affinity for external Ca2+block. This block is characterized by a reduction in unitary current often described as a “very fast” block in which the flickering between open and blocked state is so fast that the channel conductance appears lowered (Hille, 1992). In the βG522D mutant, the voltage dependence of block by Ca2+predicts a Ca2+ interaction with the channel at a site located 15% within the transmembrane electric field. This voltage-dependence of Ca2+ block is similar to that reported for ENaC block by amiloride, further supporting the notion that the βG522 and likely the adjacent βG525 residues within pre-M2 segment are involved in an external amiloride binding site (Palmer, 1985).

Cys substitution at αS583 position renders the channel sensitive to block by external Zn2+ions with a K i in the μM range. The flickering channel behavior induced by Zn2+is very similar to channel block by amiloride with rapid opening and closing events lasting <100 ms and a slight voltage dependence (Palmer and Frindt, 1986). Coordination of Zn2+with the sulfhydryl group of Cys at position 583 in the α subunit further decreased channel affinity for amiloride, as shown by the competitive interaction between these two blocking molecules. Thus Zn2+ ions have similar blocking effects than amiloride when binding a common site within the transmembrane electric field.

All the divalent blocking experiments provide strong evidence that the Ser580 and Ser583 as well as the corresponding Gly residues in the β and γ subunits are accessible by external cations and are facing the ion permeation pathway. The location of these residues within the transmembrane electric field suggest that the pre-M2 segment forms the outer entrance of the channel pore.

ENaC Channel Pore

In a model proposed by Palmer and based on diverse functional experimental findings, the ENaC channel pore can be envisioned as a progressively narrowing funnel that allows only the smallest monovalent cations such as H+, Li+, or Na+ to permeate the channel (Palmer, 1990). The outer mouth of the channel accept blocking cations with a molecular diameter of <5 Å which bind with low affinity at a single site located at ∼15% of the transmembrane electric field. Several pieces of evidence support the notion that amiloride is a channel pore blocker, plugging the conducting pore and preventing ion permeation. These evidences include a voltage dependence of amiloride block very similar to that measured for monovalent and divalent cations and the interactions between amiloride and permeating or blocking cations (Palmer, 1985, 1990). According to its size, only the guanidinium moiety of amiloride would be able to reach the outer mouth of the channel.

In support of this model are the observations that residues in αβγ subunits involved in amiloride binding are facing the ion permeation pathway, and the striking similarity between amiloride and Zn2+ blocking effects when binding at a commun site. The molecular mechanism underlying channel block by amiloride is not yet understood. Evidence for competitive interactions between permeating Na+ions and amiloride has been provided in experiments where lowering external Na+increased the association rate constant for amiloride (Palmer and Andersen, 1989). In our study, βG525C and γG537C mutations decrease channel conductance and coexpression of these mutations with the corresponding mutation S583C in the α subunit resulted in a nonconducting channel expressed at the cell surface. This indicates that these residues are important for both ion permeation and amiloride binding. The lower single channel conductance observed for mutations that have the more dramatic effect on amiloride K i are consistent with a binding interaction between amiloride and Na+ ions at an external Na+binding site. Furthermore, these findings point to the role of β and γ subunits in ion permeation through the channel. The presence of amino acids in β and γ subunits that when mutated affect single channel conductance and may participate in an external Na+binding site raises questions about the ionic permeation properties of α homomeric channels, properties that have not yet been convincingly established.

A recent study has identified two Ser residues (Ser 589, Ser 593) in the M2 membrane-spanning segment of αrENaC that when mutated change unitary current and ionic selectivity of the channel (Waldmann et al., 1995b ). The Ser589 also decreased channel affinity for amiloride with a K i of ∼2 μM. According to an α helical structure of the M2 segment these Ser residues could line the conducting pore, suggesting that the M2 segment extend deeper into the channel pore where the selectivity filter could be located.

The picture of the channel pore emerging from our mutagenesis experiments is still crude but shows a pore formed by the three αβγ subunits. The question as to whether the channel pore is composed of strictly identical subunits has been debated since the identification of the heterotrimeric structure of the channel. The fact that the functional properties of heteromultimeric αβγ or δβγ channels are indistinguishable from those measured with expression of α or δ subunits alone has been interpreted as evidence that α or δ subunits are the pore-forming subunits and that the β and γ subunits represent accessory subunits modulating channel activity (Waldmann et al., 1995a ). Clearly, mutations in the β and γ subunits that change amiloride affinity, single channel conductances, and generate binding sites for channel block by divalent cations represent strong evidence that all these subunits participate in the ion permeation pathway. Thus our experiments favor a model in which the αβγ subunits are arranged pseudosymmetrically around a central conducting pore in a way similar to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. However the subunit stoichiometry of ENaC remains to be determined.

The residues identified in this study, involved in amiloride block and in ion permeation, are located in a short segment with a high degree of homology that precedes the second membrane-spanning M2 segment. Proteolytic digestion of α ENaC subunit is compatible with the presence of a short segment preceding M2 that dips into the membrane (Renard et al., 1994). This observation is consistent with the localization of βG522 within the transmembrane electric field, and suggests that the pre-M2 segment forms a pore loop structure similar to the H5 domain (or P region) of voltage-gated K or Na channel. These channels, as well as inward rectifier K channels and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels which contain two membrane-spanning segments, are thought to contain pore loops, short polypeptide segments extending from one side of the membrane to the aqueous pore of the channel (MacKinnon, 1995). In many channels these pore loops comprise the channel selectivity filter, binding sites for permeating ions and for channel blockers such as diverse neurotoxins. By analogy with these channels, the pre-M2 segment of ENaC may also form a loop region that extends to the outer entrance of the channel pore where amiloride binds at the same site as permeating ions, blocking their way into the channel pore.

Acknowledgments

We thank to B.C. Rossier, and J.-D. Horisberger for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research to L. Schild (No. 31-39435.93) and by the E. Muchamp Foundation.

Abbreviation used in this paper

- wt

wild-type

references

- Canessa CM, Merillat A-M, Rossier BC. Membrane topology of the epithelial sodium channel in intact cells. Am J Physiol. 1994a;267:C1682–C1690. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger J-D, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature (Lond) 1994b;367:463–467. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamvimonvat N, Pérez-García MT, Ranjan R, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Depth asymmetries of the pore-lining segments of the Na+channel revealed by cysteine mutagenesis. Neuron. 1996;16:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DP, García-Añoveros J. Mechanosensation and the DEG/ENaC ion channels. Science (Wash DC) 1996;273:323–324. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counillon L, Franchi A, Pouysségur J. A point mutation of the Na+/H+ exchanger gene (NHE1)and amplification of the mutated allele confer amiloride resistance upon chronic acidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4508–4512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favre I, Moczydlowski E, Schild L. Specificity for block by saxitoxin and divalent cations at a residue which determines sensitivity of sodium channel subtypes to guanidinium toxins. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:203–229. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsov, D., L. Schild, I. Gautschi, A.-M. Merillat, E. Schneeberger, and B.C. Rossier. 1996. Cell surface expression of the epithelial Na channel and a mutant causing Liddle's syndrome: a quantitative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guy HR, Durell SR. Structural model of ion selective regions of epithelial sodium channels. Biophys J. 1995;68:A243. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. 1992. Ionic Channel of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Kieber-Emmons T, Lin CM, Prammer KV, Villalobos A, Kosari F, Kleyman TR. Defining topological similarities among ion transport proteins with anti-amiloride antibodies. Kidney Int. 1995;48:956–964. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH-Y, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Lindemann B. Structure-activity relationship of amiloride analogs as blockers of epithelial Na channels: II. Side-chain modifications. J Membr Biol. 1987;95:171–185. doi: 10.1007/BF01869162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R. Pore loops: an emerging theme in ion channel structure. Neuron. 1995;14:889–892. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Families of ion channels with two hydrophobic segments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:474–483. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG. Interactions of amiloride and other blocking cations with the apical Na channel in the toad urinary bladder. J Membr Biol. 1985;87:191–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01871218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG. Epithelial Na channels: the nature of the conducting pore. Renal Physiol Biochem. 1990;13:51–58. doi: 10.1159/000173347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG, Andersen OS. Interactions of amiloride and small monovalent cations with the epithelial sodium channel. Inferences about the nature of the channel pore. Biophys J. 1989;55:779–787. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82876-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG, Frindt G. Amiloride-sensitive Na channels from the apical membrane of the rat cortical collecting tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2727–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LG, Frindt G. Gating of Na channels in the rat cortical collecting tubule: effects of voltage and membrane stretch. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:35–45. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard S, Lingueglia E, Voilley N, Lazdunski M, Barbry P. Biochemical analysis of the membrane topology of the amiloride-sensitive Na+channel. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12981–12986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier BC, Canessa CM, Schild L, Horisberger J-D. Epithelial sodium channels. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1994;3:487–496. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Canessa CM, Shimkets RA, Gautschi I, Lifton RP, Rossier BC. A mutation in the epithelial sodium channel causing Liddle disease increases channel activity in the Xenopus laevisoocyte expression system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5699–5703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild L, Lu Y, Gautschi I, Schneeberger E, Lifton RP, Rossier BC. Identification of a PY motif in the epithelial Na channel subunits as a target sequence for mutations causing channel activation found in Liddle syndrome. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:2381–2387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM, McDonald FJ, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ. Membrane topology of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24379–24383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Voilley N, Lazdunski M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a novel amiloride-sensitive Na+channel. J Biol Chem. 1995a;270:27411–27414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Lazdunski M. Functional degenerin-containing chimeras identify residues essential for amiloride-sensitive Na+channel function. J Biol Chem. 1995b;270:11735–11737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhull A. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. J Gen Physiol. 1973;61:687–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]