Abstract

Genomic imprinting has dramatic effects on placental development, as has been clearly observed in interspecific hybrid, somatic cell nuclear transfer, and uniparental embryos. In fact, the earliest defects in uniparental embryos are evident first in the extraembryonic trophoblast. We performed a microarray comparison of gynogenetic and androgenetic mouse blastocysts, which are predisposed to placental pathologies, to identify imprinted genes. In addition to identifying a large number of known imprinted genes, we discovered that the Polycomb group (PcG) gene Sfmbt2 is imprinted. Sfmbt2 is expressed preferentially from the paternal allele in early embryos, and in later stage extraembryonic tissues. A CpG island spanning the transcriptional start site is differentially methylated on the maternal allele in e14.5 placenta. Sfmbt2 is located on proximal chromosome 2, in a region known to be imprinted, but for which no genes had been identified until now. This possibly identifies a new imprinted domain within the murine genome. We further demonstrate that murine SFMBT2 protein interacts with the transcription factor YY1, similar to the Drosophila PHO-RC.

Keywords: Genomic Imprinting, Sfmbt2, PcG gene, Extraembryonic tissues, placenta, MMU2, YY1, microarrays, uniparental embryos

1. Results and Discusssion

The role played by imprinted genes in placental development is gaining wider attention as the impact of imprinting disruptions on placental pathology is explored. Both hyper- and hypoplastic placentation are linked to imprinted gene function (Kanayama et al., 2002; Murdoch et al., 2006; reviewed in Kaneko-Ishino et al., 2003). The most dramatic example of this is diploid, uniparental embryos. Gynogenetic embryos (two maternal/no paternal genomes) and androgenetic embryos (two paternal/no maternal genomes) both exhibit defects in the earliest differentiated tissue in mammals, the extraembryonic trophoblast (Barton et al., 1984; McGrath and Solter, 1984; Mann, 2005). At mid-gestation, gynogenetic embryos possess only a few residual trophoblast giant cells while androgenetic embryos are characterized by a mass of hypertrophic trophoblast. These observations indicate that a suite of genes required for correct placental development is silenced on maternally inherited chromosomes, and must be expressed from the paternally derived chromosomes.

Following the discovery of mammalian genomic imprinting in the mid 1980's, cytogenetic experiments were used to identify imprinted regions of the mouse genome. Balanced Robertsonian translocations are normally viable, except where an imprinted region is involved. Uniparental disomy for specific domains of the mouse genome that resulted in developmental defects or inviability revealed the presence of imprinted genes involved in embryogenesis (Beechey et al., 2005). One region of interest is proximal Chromosome 2, where an imprinted gene(s) was inferred to reside but for which no gene has yet been identified.

The search for imprinted genes has been aided in recent years by the use of differential screens involving either uniparental embryos (Miyoshi et al., 1998; Mizuno et al., 2002; Nikaido et al., 2003; Ruf et al., 2006), uniparental cell lines (Piras et al., 2000), or Robertsonian translocations (Schultz et al., 2006). All of these approaches are dependent on the use of quantitative amounts of starting material for the generation of probes. Of necessity, therefore, the focus was either on mid-gestation uniparental embryos, which display significant pathology, or on only mildly affected balanced translocation embryos, which are able to survive to birth. Extraembryonic tissues from parthenogenetic embryos are non-existent at mid-gestation, and in one study comparing androgenetic and fertilized embryos, extraembryonic tissues were discarded (Miyoshi et al., 1998). In the case of uniparental cell lines, only those genes expressed in tissue culture cells and retaining their imprints were open to query. All approaches were unable to address the very early effects of parental-origin on trophoblast development.

Phenotypic differences between uniparental mouse embryos commence shortly after implantation, and affect the trophoblast most profoundly at these early stages (Surani et al., 1986; Varmuza et al., 1993). In order to identify imprinted genes contributing to trophoblast development before the onset of severe placental pathology, we performed microarray analysis on androgenetic, gynogenetic and biparental blastocyst cDNA. From this screen we were able to identify the PcG gene Sfmbt2 (Sex combs on the midleg with four MBT domains), which maps to the proximal region of Chromosome 2, as a putative imprinted gene. Our experiments demonstrate that Sfmbt2 is paternally expressed in early embryos and later stage extraembryonic tissues, confirming its imprinted status. The recent identification of a third PcG silencing complex in Drosophila (Klymenko et al., 2006) composed minimally of dSfmbt and Pleiohomeotic (Pho) or Pho-like (Phol), Drosophila ortholgues of the mammalian YY1 transcription factor, prompted us to investigate the possibility that murine SFMBT2 and YY1 may form a similar silencing complex. We found that Yy1 is expressed in quantitatively similar amounts as Sfmbt2 in extraembryonic tissues, and moreover that SFMBT2 and YY1 proteins interact in mammalian tissue culture cells following transfection of expression contructs.

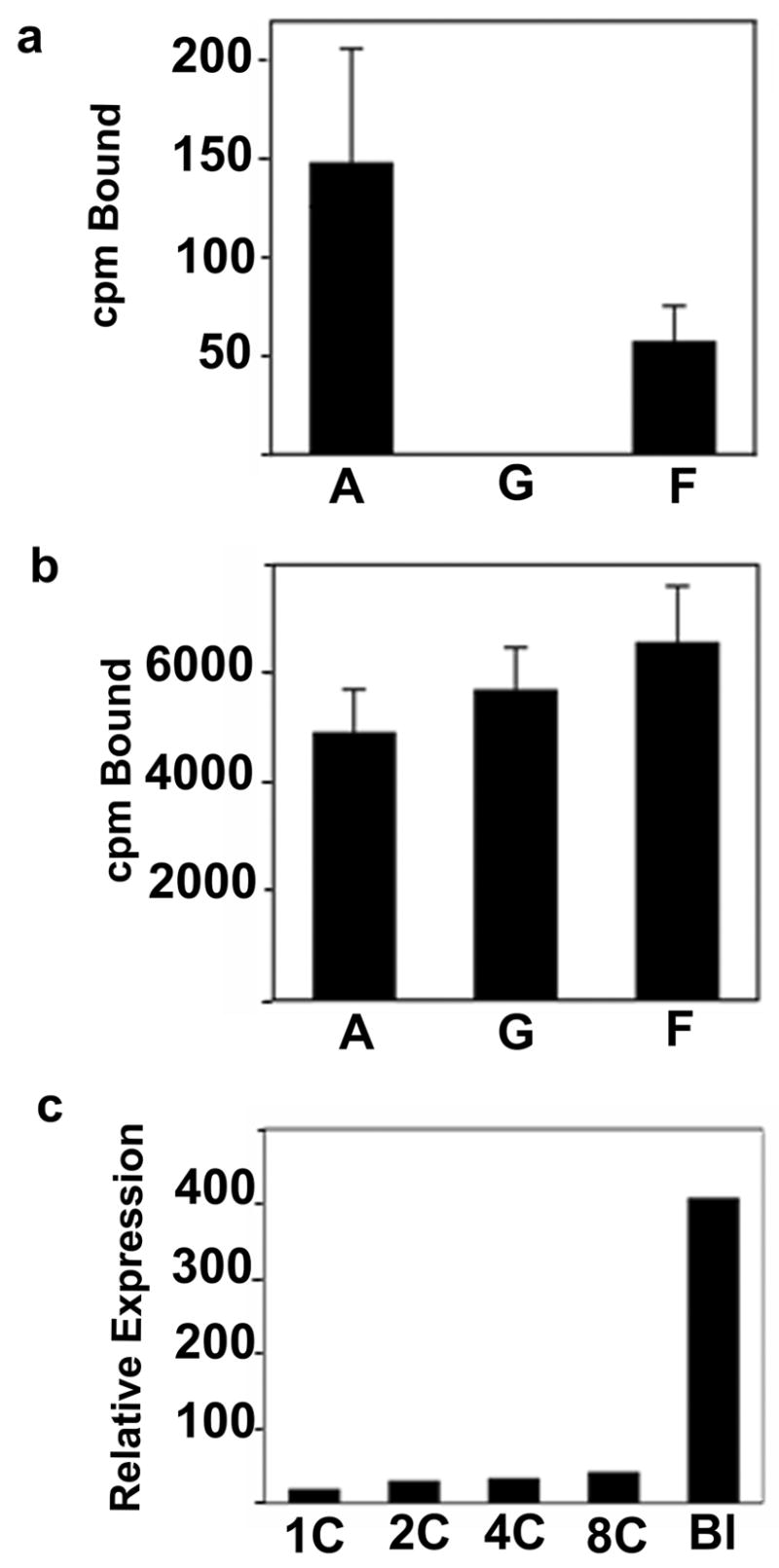

1.1 Microarray Screen

Early defects in uniparental embryos are difficult to study because of the limiting amounts of biological material available for analysis. We relied on a PCR based technology for generating quantitative pools of cDNA from very small samples (Iscove et al., 2002). Three different pools of cDNA derived from androgenetic, gynogenetic or biparental blastocysts were labeled and applied to Affymetrix MOE430 A and B expression arrays. The data were analyzed with ArrayAssist 2.0 software, using a p<0.01 statistical limit on variation, and selecting genes displaying a minimum 4 fold (ln=2) difference between experimental and baseline (biparental) samples. The statistical parameters allowed the capture of several known imprinted genes. Data were exported to Excel, and sorted according to average absolute difference between androgenetic and gynogenetic samples (Table 1). An arbitrary difference of 3.0 (8 fold) was chosen as the threshold. One hundred and twenty seven (127) genes reached or surpassed the threshold difference in expression levels in uniparental embryos. While 41.7% of these genes map to regions of the mouse genome known to contain imprinted genes from the translocation studies (Beechey et al., 2005), it should be pointed out that there may be imprinted genes that do not affect either viability or morphology because of functional redundancy with non-imprinted genes, and that the imprint map is therefore an under-representation of imprinted regions. In a similar vein, significant numbers of non-imprinted genes are expected to be identified in this kind of screen because of pathological differences between uniparental embryos, although we tried to minimize this effect by using blastocysts. The small number of genes displaying differential expression in our screen likely reflects both the reduced size of the transcriptome at the blastocyst stage, and the relatively similar phenotype of uniparental and biparental blastocysts. The two genes with the greatest difference, Slc38a4, and Mcts2, are both imprinted, paternally expressed genes (Beechey et al., 2005). The next gene with the third largest expression difference is Sfmbt2, a PcG gene mapping to MMU2A1. For comparison, the expression differential for four other known imprinted genes is shown in Table 1. Quantitative expression analysis of Sfmbt2 confirmed that Sfmbt2 mRNA is essentially absent in gynogenotes (Fig. 1A), while displaying slightly elevated expression in androgenotes. The control Eef1a1 gene was expressed at levels very similar among the three embryo types, as expected for a non-imprinted gene, confirming successful cDNA amplification (Fig. 1B).

Table 1. Differential Expression of Imprinted Genes in Androgenetic and Gynogenetic Blastocysts.

| Gene | Expressed allele | Differential (fold) | Up in Andros Down in Gynos | Up in Gynos Down in Andros |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slc38a4 | Paternal | 10.6 (1552) | yes | |

| Mcts2 | Paternal | 9.2 (588) | yes | |

| Sfmbt2 | Paternal (this study) | 8.6 (388) | yes | |

| Plagl1 | Paternal | 6.3 (78) | yes | |

| Osbpl5 | Maternal | 4.0 (16) | yes | |

| H19 | Maternal | 3.4 (10.6) | yes | |

| Gtl2 | Maternal | 3.0 (8.0) | yes |

Microarray data were analysed with ArrayAssist 2.0, and those genes with a minimum 4-fold (ln 2) difference between either androgenetic and biparental or gynogenetic and biparental probes were ranked according to the absolute difference between androgenetic and gynogenetic probes. Selected imprinted genes (Beechey at al., 2005) are included to illustrate the range of expression differences.

Figure 1.

Sfmbt2 expression in biparental and uniparental embryos during preimplantation development. (a) Confirmation of differential expression of Sfmbt2 in androgenetic (A), gynogenetic (G), and biparental reconstituted (F) blastocysts. Data were obtained by the QABD method (see Experimental procedures), and are expressed in units of counts per minute (cpm) of probe bound on dot blots. (b) Expression of control Eef1a1 in the three types of embryos, also produced using the QABD method. (c) DNA array-based expression data for Sfmbt2 during mouse preimplantation development. Data were compiled from Zeng et al., 2004 and depict the average fluorescence intensities from four hybridized arrays per stage. Stages shown correspond to one cell (1C), 2 cell (2C), 4 cell (4C), 8 cell (8C), blastocyst (Bl). Expression from 1C to 8C likely represents basal level of transcription.

1.2 Sfmbt2 Displays Monoallelic Expression

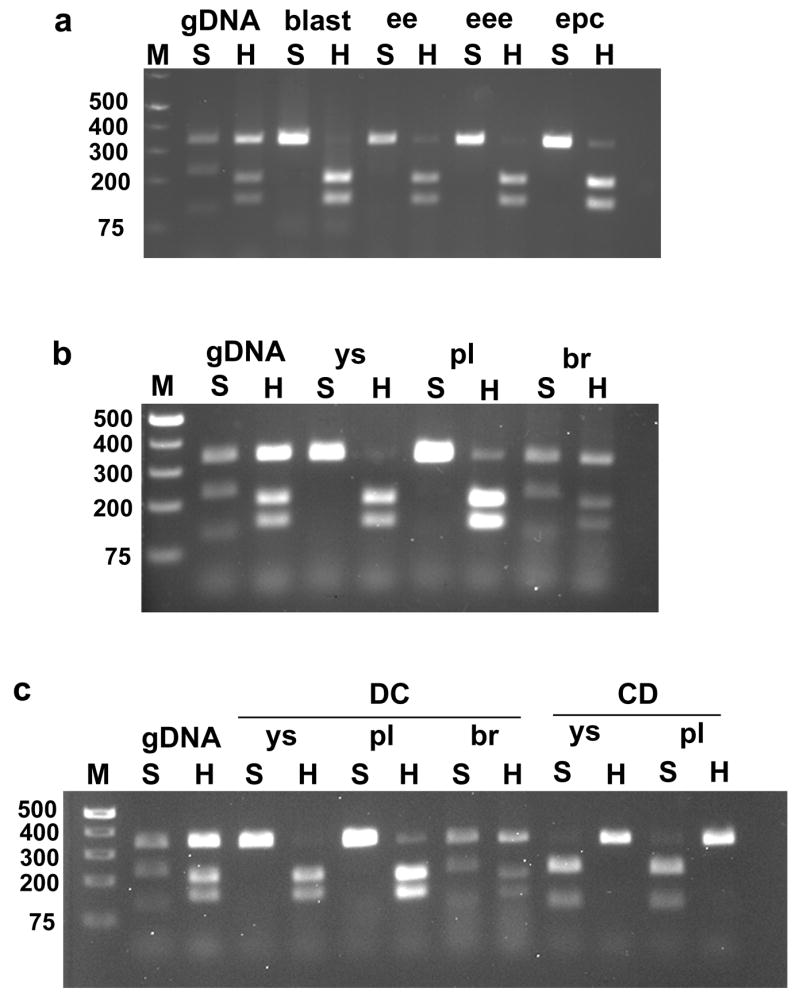

Imprinted genes are expressed from only one parental allele in at least one tissue or at one stage of development. To determine the imprint status of Sfmbt2, allelic expression was assessed in M. mus. domesticus X M. mus. castaneus F1 embryos. Two SNPs mapping within a 340 bp segment of the 3′ UTR generate strain-specific restriction polymorphisms; SnaBI cleaves the M. mus. domesticus allele into 226 and 114 bp fragments, while HinfI digests the M. mus. castaneus allele into 199 and 141 bp fragments. cDNA derived from embryo or extraembryonic tissues from M. mus. domesticus X M. mus. castaneus, or the reciprocal M. mus castaneus X M. mus. domesticus F1 progeny was assessed for allelic expression. Sfmbt2 is expressed preferentially from the paternal allele in blastocysts, embryonic day (e) 7.5 tissues, e11.5 and e14.5 yolk sac and placenta, but is biallelically expressed in e11.5 and e14.5 brain (Fig. 2), and other somatic tissues (not shown). Thus, Sfmbt2 is imprinted in early embryos and extraembryonic tissues, but loses its imprint in somatic tissues after e7.5.

Figure 2.

Sfmbt2 is expressed from the paternal allele in early embryos and extraembryonic tissues. (a) Genomic DNA (gDNA), or cDNA derived from Domesticus X Castaneus (DC) F1 e3.5 blastocysys (blast), e7.5 embryonic ectoderm (ee), e7.5 extraembryonic ectoderm (eee) or e7.5 ectoplacental cone (epc) was amplified with Sfmbt2SNP4103 forward and reverse primers (Table 2). This generates a 340 bp fragment from the 3′ UTR. Digestion of this PCR product with SnaBI (S) generates 226 and 114 bp fragments from the Domesticus allele, but does not digest the Castaneus allele. Digestion of the fragment with HinfI (H) generates 199 and 141 bp fragments from the Castaneus allele, but does not digest the Domesticus allele. b) Genomic DNA (gDNA) or cDNA from DC F1 e11.5 yolk sac (ys), placenta (pl) or brain (br) was amplified and disgested as described in a). c) cDNA from DC F1 e14.5 ys, pl, and br, and from e14.5 CD ys and pl was amplified and digested as described in a).

1.3 Sfmbt2 Promoter Region Displays Maternal Methylation in Placenta

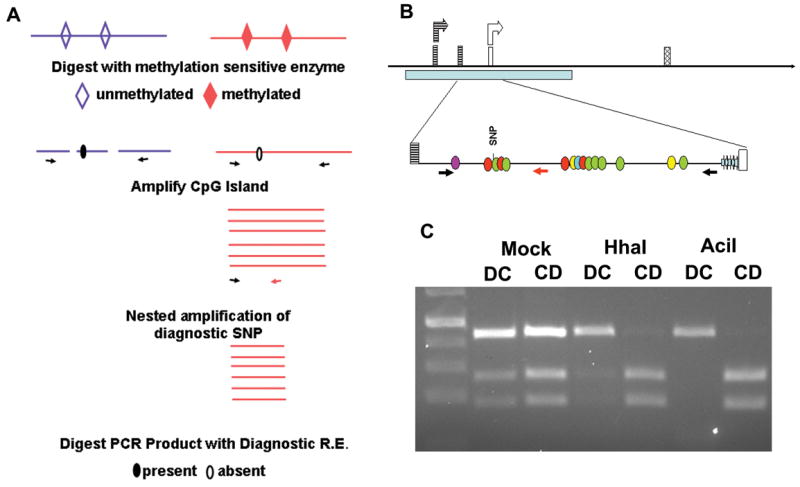

Imprinted genes are regulated by imprinting control regions (ICRs) which are associated with blocks of tandem repeats and differential methylation (Hutter et al., 2006; Verona et al., 2003). We examined the published sequence for Sfmbt2 and found a CpG cluster near the transcriptional start site. Two starts are annotated for Sfmbt2, suggesting the presence of two promoters. For one of these, the most 5′, and herein referred to as Promoter 1, there are three leader exons that are differentially spliced onto the first common exon (published EST database, and not shown). The second start site (Promoter 2) splices a different leader exon onto the first common exon. The CpG island, which is approximately 6500 bp in length, spans both starts, including all of the leader exons and part of the first major intron. Across the CpG island there was only one SNP differentiating Mus castaneus and Mus domesticus, an MseI site upstream of the Promoter2 start. This necessitated a strategy involving nested PCR of surviving allelic sequences following digestion of F1 genomic DNA with methylation sensitive enzymes (Fig 3A). Adjacent to the start site for Promoter 2 lies a block of imperfect repeats that are highly GC-rich (83%), and that inhibited PCR (Fig 3B); we therefore queried the segment of the CpG island upstream of Promoter 2 that contained the single diagnostic SNP. Analysis of the 1340 bp region 5′ of the repeats revealed that the inactive maternal allele is hypermethylated while the active paternal allele in hypomethylated in e14.5 placentas (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

The promoter region of Sfmbt2 displays maternal methylation.

(a) Methylation sensitive PCR strategy. Illustrated is the outcome in a DC cross, where the maternal Domesticus allele, which lacks the MseI site, survives digestion with a variety of methylation sensitive enzymes. MseI is a frequent cutter (TTAA), thus necessitating nested PCR following digestion of genomic DNA and amplification of the CpG island.

(b) Schematic diagram of Sfmbt2 promoter region. Two start sites corresponding to Promoter 1 (striped boxes) and Promoter 2 (open boxes) generate two different leader 5′ UTRs that are spliced onto the first common exon (hatched). A CpG cluster spans both start sites (pale blue bar), including a 57 bp block of imperfect GC-rich repeats (thick, pale blue arrows, not to scale, bottom line) immediately 5′ of Promoter 2. Methylation-sensitive CpGs are indicated by coloured circles (BsmBI, purple; HhaI, red; AciI, green; HpaII, yellow; SmaI, turquoise). (c) Genomic DNA from e14.5 DC or CD F1 placentas was digested overnight with methylation sensitive restriction enzymes, or with buffer alone (mock). Digested DNA was amplified with PrDMRCastF1 and PrDMRR11 primers (Table 2). The resulting PCR product was subjected to 10 cycles of nested PCR with PrDMRCastF1 and PrDMRCastR1. This generates a 447 bp fragment that contains a polymorphic SNP. Digestion of the Castaneus allele with MseI generates 265 bp and 182 bp fragments, while the Domesticus allele remains undigested. Illustrated here are the results for genomic DNA digested with HhaI or AciI. Similar results were obtained following digestion with SmaI, BsmBI, HpaII, and various combinations.

1.4 Sfmbt2 is Expressed Robustly in Extraembryonic Tissues

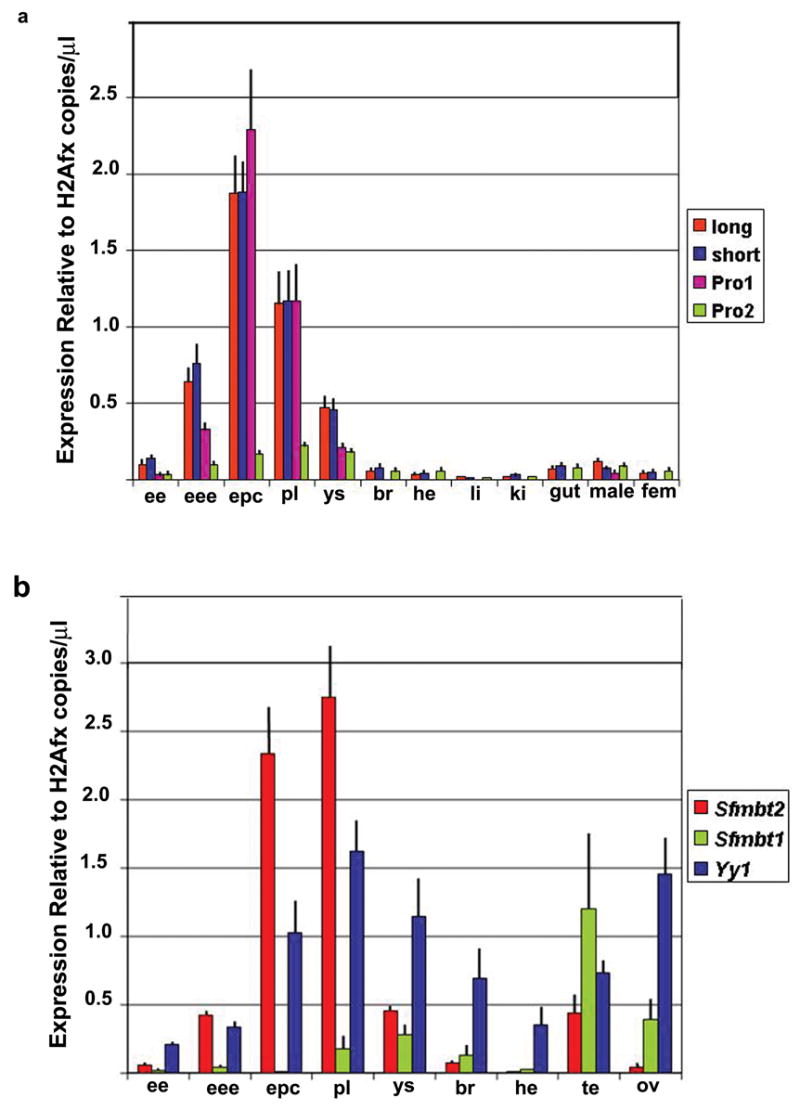

Two start and two stop sites are annotated for Sfmbt2. RT-PCR confirmed that all combinations of starts and stops are used (not shown). The shorter isoform, which is predicted to encode a truncated protein containing only one MBT domain, results from the use of a polyA site within exon 6. Expression of Sfmbt2 in preimplantation embryos is characteristic of a group of genes with a mid-preimplantation gene activation pattern, when major embryonic expression commences between the 8-cell and blastocyst stage (Fig1C), as assessed from published microarray data (Zeng et al, 2004; Hamatani et al., Dev Cell, 2004). Genes with this expression pattern have been purported to have roles in blastocyst formation and the emergence of distinct cell types in the preimplantaion embryo. We examined expression of Sfmbt2 by quantitative (q) RT-PCR in e7.5 and e14.5 tissues. Using primers that distinguish the two alternative starts and stops, we established that Promoter 1 is the predominant transcription start site, and that both termination sites are used equivalently (Fig. 4A). Overall, expression of Sfmbt2 is high in extraembryonic tissues, and low in somatic tissues. Sfmbt2 is paralogous with the closely related Sfmbt1. For tissues examined, expression of the two genes is roughly reciprocal (Fig 4B). In early embryos, Sfmbt2 is the only paralogue detected.

Figure 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis of Sfmbt1, Sfmbt2 and Yy1 Transcripts at embryonic day 7.5 and 14.5. (a) Expression profiles of long and short Sfmbt2 isoforms and of transcripts originating from promoter 1 and 2 in various tissues. (b) Expression profiles of Sfmbt1, Sfmbt2 (long) and Yy1 in various tissues. Expression was normalized to that of the histone variant H2afx, which is expressed at roughly comparable levels to Sfmbt2 in extraembryonic tissues, and within a narrow range across all tissues sampled. e7.5 embryonic ectoderm (ee), extraembryonic ectoderm (eee) and ectoplacental cone (epc); e14.5 placenta (pl), yolk sac (ys), brain (br), heart (he), liver (li), kidney (ki), gut, male genital ridge (male) and female genital ridge (fem); adult testis (te) and ovary (ov). Each experiment was performed three times in duplicate. Bars represent standard deviation.

Gene silencing during development is mediated by the PcG complexes PRC1 and PRC2, which together promote histone modifications (Sparmann and van Lohuizen, 2006). Recent evidence in Drosophila revealed the existence of a third silencing complex called Pleiohomeotic-repressive complex (PHO-RC) (Klymenko et al., 2006), that is similar to but functionally distinct from PRC1 and PRC2. PHO-RC is composed minimally of dSfmbt and either Pho or Phol, orthologues of the mammalian YingYang1 (YY1) transcription factor. We examined expression of Yy1 in e7.5 and e14.5 tissues and found that it is coincident with Sfmbt2 in early embryos and extraembryonic tissues (Fig. 4B), lending support to the idea that mammalian SFMBT2 and YY1 proteins may act in concert, similar to their fly counterparts.

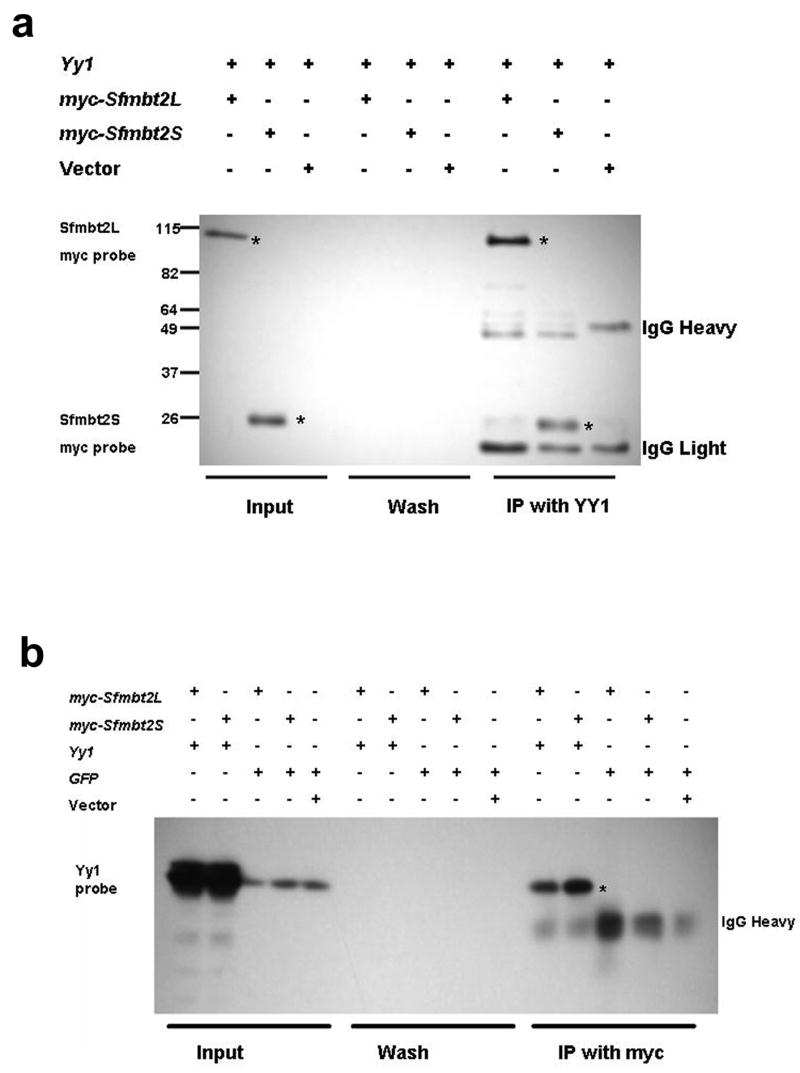

1.5 SFMBT2 and YY1 Interact in Mammalian Cells

To assess the potential for formation of a PHO-RC in mammals, we expressed myc-tagged SFMBT2 long or short isoforms, with a murine YY1 expression vector in HEK293 cells. Co-immunoprecipitation with either anti-myc or anti-YY1 antibodies revealed that both long and short SFMBT2 isoforms interact strongly with YY1 (Fig. 5) whereas extracts precipitated using a control GFP antibody failed to show any interaction (data not shown). These experiments indicate that both isoforms of SFMBT2 and YY1 are components of a stable protein complex, possibly PHO-RC. As the shorter isoform is predicted to encode a protein possessing no sterile alpha motif domain, the YY1 interacting domain likely resides in the SFMBT2 NH3 terminus, which harbours one MBT domain. Whether this lone MBT domain is sufficient for SFMBT2-YY1 interaction remains to be tested.

Figure 5.

Mouse SFMBT2 interacts with YY1 to form a mammalian PHO-like complex. (a) Western blot analysis of Myc-tagged SFMBT2 isoforms. HEK 293 cells were transfected with the indicated combinations of expression vectors. Immunoprecipitations were performed using a YY1 antibody, and blots were probed with an anti-myc antibody. The long isoform produced a 110 kDa protein whereas the shorter isoform produced a 25 kDa protein (asterisks in lanes 7 and 8, respectively indicate the SFMBT2 isoforms that co-immunoprecipitated with YY1). (b) HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with the indicated expression constructs, and protein extracts were immunoprecipitated using an anti-myc antibody. Blots were probed with anti-YY1. Both isoforms of SFMBT2 interacted with YY1 (lanes 11 and 12, asterisk).

We have discovered a new imprinted gene, Sfmbt2, which is preferentially expressed from the paternal allele in the developing placenta. As a likely member of a recently identified chromatin regulatory complex, PHO-RC, Sfmbt2 is distinguished from other known murine imprinted genes as the first imprinted Polycomb group gene. Only one other imprinted gene is known to encode a chromatin regulatory protein. Human L3MBTL is expressed from the paternal allele in human blood cells (Li et al., 2004); however, the murine orthologue of L3mbtl is not imprinted (Li et al., 2005).

Sfmbt2 maps to proximal mouse chromosome 2, a known imprinted region (Beechey et al., 2005) for which no imprinted genes have been identified until now. Sfmbt2 is the first imprinted gene within this region to be identified. Previous studies had indicated that six different translocations involving proximal chromosome 2 resulted in lethality when present as a maternal uniparental duplication (Cattanach et al., 2004). In this same paper, the authors also reported that three more distal duplications of proximal chromosome 2 were not lethal when maternally duplicated, paternally deleted. Instead, maternal disomy resulted in fetal and placental growth reduction while paternal disomy produced placental growth enhancement, pointing to at least one imprinted gene involved in placental development. While the authors interpret their results as evidence that proximal chromosome 2 does not contain any genes required for viability, we offer an alternative interpretation of the presented data, and suggest that the three distal translocation chromosomes may be providing evidence of an epistatic interaction, likely with a the central region of chromosome 2. Our explanation would explain the viability of the three distal translocation chromosomes and the lethality of the other six translocation chromosomes when maternally duplicated, paternally deleted. The most proximal of the lethal translocation chromosomes, T68H, has a breakpoint mapping to 2A3; Sfmbt2 maps to the middle of 2A1, well within the presumed lethal region. Thus, Sfmbt2 is a candidate for the placental growth effect in this epistatic interaction, as well as lethality in the absence of this interaction.

Extraembryonic trophoblast is particularly sensitive to perturbations in genomic imprinting. It is the first differentiated tissue to arise in mammalian embryos, and has been demonstrated to be adversely affected in various pathological states arising from dysregulation of imprinting. Mutations in several imprinted genes affect the trophoblast exclusivley (Coan et al., 2005; Kaneko-Ishino et al., 2003). Defects in the trans-acting machinery that regulates imprinting, such as DNA methyltransferase deficiency (Lei et al., 1996; Bourc'his et al., 2001; Hata et al., 2002; Kaneda et al., 2004; Arima et al., 2006) or mutations causing familial hydatidiform moles (Judson et al., 2002; Murdoch et al., 2006) result in abnormal placentation. Finally, interspecific hybrids (Vrana et al., 1998; Vrana et al., 2000), somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos (Dindot et al., 2004; Inoue et al., 2002) and uniparental embryos (Surani et al., 1986; Varmuza et al., 1993; Mann 2005) all suffer from dysmorphic trophoblast, in part or in whole because of abnormal expression of imprinted genes.

Of the approximately 55 protein-encoding imprinted genes that have been identified, roughly 20% can be classified as having a “placental only” imprinting (Ferguson-Smith, et al., 2006; Wagshcal and Feil, 2006), that is while expressed in tissues of both embryonal and placental origin, expression is monoallelic in placenta but biallelic in embryonic cell lineages. Our analysis of Sfmbt2 imprinted expression has revealed that this gene fits the classification of a placental only imprinted gene. Interestingly, all of the genes exhibit paternal allele-specific expression, including Sfmbt2 (Wagschal and Feil, 2006; herein). Functions prescribed to placental only imprinted genes are placental development, growth and function (Wagschal and Feil, 2006; Reik and Lewis, 2005). It is postulated that the imprinted expression patterns of this class of genes is mechanistically similar to imprinted X inactivation, and that imprinting of these genes may have arisen in ancestral placental mammals (Wagschal and Feil, 2006; Reik and Lewis, 2005).

The PcG silencing complexes PRC1 and PRC2 have been implicated in mammals with the maintenance of stem cell populations and the development of cancer (Sparmann and van Lohuizen, 2006). Recently, a new repressive complex called PHO-RC was identified in Drosophila that is composed minimally of dSfmbt and PHO or PHOL, the fly orthologues of the transcription factor YY1 (Klymenko et al., 2006). The role played by PHO-RC in development is a new avenue of research. It will be particularly interesting to determine whether Sfmbt2 regulates TS cell maintenance.

We observed that SFMBT2 and YY1 interact strongly in tissue culture cells transfected with expression constructs, suggesting that they do so in vivo. Support for this finding comes from expression studies indicating that the Sfmbt2 and Yy1 genes are co-expressed in early embryos and extraembryonic tissues (Donohoe et al., 1999; Frankenberg et al., 2007; this study). Furthermore, the phenotype of Yy1 null embryos is very similar to that of gynogenetic embryos, with lethality occurring just after implantation (Donohoe et al., 1999). Yy1 null blastocysts form outgrowths bearing a striking resemblance to gynogenetic blastocyst outgrowths, with reduced proliferation of both inner cell mass and trophoblast cells (Donohoe et al., 2007). A coherent working hypothesis posits that SFMBT2 and YY1 form the core of a mammalian PHO-RC silencing complex that is required in early mouse embryos to maintain the TS cell population. This hypothesis is currently under investigation.

The discovery that the PcG gene Sfmbt2 is paternally, and robustly, expressed in early embryos opens up an exciting new avenue of research in trophoblast biology and placentation. Investigation of the downstream targets of SFMBT2 regulation across a range of mammalian species will provide insight into trophoblast, a specialized cell type that is characterized in mice and humans by its ability to invade other tissues. In addition, the study of a new gene silencing complex in mammals will add to our growing understanding of epigenetic regulation of both normal and pathological processes.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1 Production and Culture of Embryos

Adult C57BL/6 (Harlan Sprague Dawley) female mice were superovulated and mated to AKR/J, DBA/2 or (DBA/2XC57BL/6)F1 males. Androgenetic (two paternal pronuclei) and gynogenetic (two maternal pronuclei) were prepared by pronuclear transfer as described (Latham et al., 2000). Embryos were cultured in CZB medium until the 8-cell stage and then in Whitten's medium, and processed for RNA extraction at 118 hours post hCG injection of females (preparation of microarray cDNA), or 121 hours post hCG (Quantitative Amplification and Dot Blotting, QADB analysis; Latham et al, 2000). All experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care, or the United States National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2 Preparation of cDNA from Uniparental Blastocysts

RNA was extracted from three separate pools of 10 blastocysts and used for synthesis of cDNA using as described (Latham et al., 2000). With this method, the entire population of reverse transcribed cDNAs is transcribed under conditions that quantitatively maintain individual sequence representation. cDNA was submitted to the Microarray Facility of the Ontario Genomics Innovation Centre, Ontario Health Research Institute for labeling and hybridization to Affymetrix MOE 430 A and B chips, using a protocol described in Iscove et al., 2002. Microarray data have been deposited with NCBI GEO, accession number GSE8163. The experiment (Stembase experiment 235) is part of a large collection of microarray experiments aimed at analyzing stem cell function (Perez-Iratxeta, et al., 2005). Microarray data were analysed with ArrayAssist 2.0 (Stratagene). QADB analysis of Sfmbt2 expression in uniparental embryos was performed as described in Latham et al, 2000 using a probe generated by RT-PCR amplification with Sfmbt2 3′end forward and reverse primers (Table 2). Expression data are expressed in units of bound cpm of probe hybridized to each sample on the filters. Bars indicate the average (± s.e.m.) of expression for single androgenetic (n=34), gynogenetic (n=7), and biparental (n=24) blastocysts. Expression data of Sfmbt2 through preimplantation development were compiled from Zeng et al., 2004.

Table 2. Primer Sequences.

| SNP analysis | Sfmbt2SNP4103F | CACATGGAAAGCAAGCACAA |

| Sfmbt2SNP4103R | CTGATTAGTCTACAAATGACTTAGC | |

| QABD probe | Sfmbt2 3′endF | TCGGGATCTTTGTTGGTTTG |

| Sfmbt2 3′endR | AAGGGCTCCCACCTTTAGTG | |

| Long transcript template | Sfmbt2F | TCTGGGGACATCTACTGCTTG |

| Sfmbt2R | TGTGACATGGCCTACAGCTC | |

| Long transcript qRT-PCR | Sfmbt2Fi | TAACTGCTGTCCTGCCTGCT |

| Sfmbt2R | TGTGACATGGCCTACAGCTC | |

| Short transcript template | Sfmbt2short3′endF | TTCCTGTTTATTAACTGAATTCCATA |

| Sfmbt2short3′endR | TGCTGCTTAACTTGGGCATT | |

| Short transcript qRT-PCR | Sfmbt2shortnestedF | TGGTGTTGTTGCGGATAAGA |

| Sfmbt2shortnestedR | TCTTGGCATGTGAAGAGTGC | |

| Promoter 1 template | Sfmbt2pr1oF | TGGGTCTTGTGGGTCTAAGC |

| Sfmbt2pr1oR | TCATTTTCCTCCAGGTTGGT | |

| Promoter 1 qRT-PCR | Sfmbt2pr1iF | GAGCCTCTTTCCCACCTCTT |

| Sfmbt2pr1iR | TGCTGAGCCGGTTATCTTTT | |

| Promoter 2 template | SfPro2F2 | GTAGAGAGCGAGCGAGCAAG |

| Sfmbt2pr2oR | CACCGCTCTGGTACCTGTCT | |

| Promoter 2 qRT-PCR | Sfmbt2pr2iF | TGTAGTGGGAGCTGGAGGAC |

| Sfmbt2pr2iR | GAGTTGCGCTTCTTCGAAAC | |

| Sfmbt1 template | Sfmbt1F | TGCAGATGATGGAGACGAAG |

| Sfmbt1R | GTGCTTCAAAGACCCAGCTC | |

| Sfmbt1 qRT-PCR | Sfmbt1innerF | CACGCAGACCAACAAGAGAG |

| Sfmbt1innerR | GGGCCCAACTTTAAGTCCAT | |

| YY1 template and qRT-PCR | YY1innerF2 | CGCTAAAGCCAAAAACAACC |

| YY1innerR2 | TGAAACGAGATTACAGAGCAAGA | |

| H2Afx template | H2AfxFo | CGTCTTTGCTTCAGCTTGGT |

| H2AfxRo | TCCAGTTCAGAAGCCAGAGG | |

| H2Afx qRT-PCR | H2AfxFi | CATTGTTTCCTTCGGTGTCA |

| H2AfxRi | AAGCGTCTCGACCCTTG | |

| DMR long | PrDMRCastF1 | CGGCGGGTGATAAAAGTGT |

| PrDMRR11 | CCTTCAACTCCCTCCACAAG | |

| DMR nested | PrDMRCastF1 | CGGCGGGTGATAAAAGTGT |

| PrDMRCastR1 | CACCCTCCCTGATCCTAACA |

2.3 cDNA Synthesis and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from indicated tissues using Trizol reagent, and following manufacturer's instructions. For blastocysts, a PicoPure kit (Arcturus) was used to extract RNA prior to cDNA synthesis. Each reverse transcriptase reaction was preceded by treatment of RNA with DNAse I for 30 minutes, followed by heat inactivation. Reverse transcription was performed with SuperScriptIII (Invitrogen) and random hexamers (Fermentas). cDNA was then used for PCR amplification using indicated primers. Optimal conditions for each primer pair were individually assessed. All zero RT controls were negative, indicating the samples were not contaminated with genomic DNA. PCR product was digested with diagnostic restriction enzymes as indicated.

2.4 Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a RotorGene 6000 Light Cycler (Corbett Life Science). Template DNA was prepared by RT-PCR from cDNA (either placenta or testis), column purified with an IsoPure DNA purification kit (Denville Scientific), and the DNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Template DNA was used to generate standard curves for comparison with cDNA following PCR amplification in the presence of SybrGreen with nested primers. Each experiment was performed in duplicate three times on cDNA that had been aliquoted to prevent freeze-thaw degradation. Data were normalized to the average value for H2Afx, and then expressed as an average ratio ± standard deviation. H2afx, a minor histone variant, was chosen because the expression levels are similar to Sfmbt2 in extraembryonic tissues. Expression of H2afx in various tissues is comparable.

2.5 Genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was extracted with an UltraClean Tissue DNA kit (MoBio). In some cases, DNA was obtained following overnight digestion with Proteinase K and phenol extraction. For analysis of the differentially methylated promoter region, placental DNA from Mus musculus domesticus X Mus musculus Castaneus F1 e11.5 or e14.5 embryos was digested with methylation sensitive enzymes (AciI, BsmBI, New England Biolabs; HhaI, HpaII, SmaI, Fermentas), or with restriction enzyme buffer alone (mock) overnight prior to PCR amplification with the DMR long primers. PCR product from the first amplification was subjected to ten cycles of PCR with DMR nested primers prior to digestion with the diagnostic restriction enzyme (MseI, Fermentas). DC F1 embryos were obtained by mating either C57BL6 females or CD-1 females bred in-house with Mus musculus Castaneus (JAX) males. CD F1 embryos were obtained by crossing F1 females with CD-1 males. Tissues from each embryo were dissected separately. The embryonic tail from each embryo was used to prepare DNA for genotyping, using the Sfmbt2SNP4103 forward and reverse primers, followed by digestion with SnaBI and HinfI. Those embryos which were heterozygous for the M.m. domesticus and M.m. castaneus alleles of Sfmbt2 were processed further.

2.6 Co-Immunoprecipitation

All methods employed are based on protocols described by Donohoe et al., 2007. HEK 293 cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-mYy1 as well as either a pcDNA3 vector expressing an amino-terminally Myc-tagged Sfmbt2 short or long isoform, using calcium phosphate-mediated co-precipitation. As a control, cells were transfected with an empty pcDNA3 Myc vector or a pcDNA3 GFP expression construct. Cells were cultured for 72 hours, transferred onto ice, washed twice with ice cold PBS and cell lysates harvested with 350mM NaCl, 50mM HEPES (pH7), 0.1% NP40, 1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT and 2 × complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). Immunoprecipitation were carried out using either the YY1 (1.5ug, Santa Cruz Biotechnology H10), Myc (1μg, Upstate 4A6) or GFP (1.5μg, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Precipitations were carried out using Protein-G Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) and washed five times using 350mM NaCl, 50mM HEPES (pH7), 0.1% NP40, 1mM EDTA, and 2 × complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). IPs were carried out using a 12 hour incubation period and eluted fractions separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membrane (BioRad) for western blot analysis. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in PBS - 0.1% Tween-20 overnight at 4°C and blotted with either α-Yy1, α-Myc or α-GFP antibodies for one hour. Following incubation with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, (co-)immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Western Lightning Perkin Elmer).

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Marnie Halpern for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada to S.V., from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to M.M., and from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (HD41440) and the National Center for Research Resources (RR15253) to K.L. M.C.G is a CIHR Postdoctoral Fellow.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arima T, Hata K, Tanaka S, Kusumi M, Li E, Kato K, Shiota K, Sasaki H, Norio W. Loss of the maternal imprint in Dnmt3Lmat-/- mice leads to a differentiation defect in the extraembryonic tissue. Dev Biol. 2006;297:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton S, Surani MA, Norris M. Role of paternal and maternal genomes in mouse development. Nature. 1984;311:374–376. doi: 10.1038/311374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beechey CV, Cattanach BM, Blake A, Peters J. MRC Mammalian Genetics Unit; Harwell, Oxfordshire: 2005. World Wide Web Site - Genetic and Physical Imprinting Map of the Mouse ( http://www.mgu.har.mrc.ac.uk.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca:2048/research/imprinting/) [Google Scholar]

- Bourc'his D, Xu GL, Lin CS, Bollman B, Bestor TH. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science. 2001;294:2536–2539. doi: 10.1126/science.1065848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattanach BM, Beechey CV, Peters J. Interactions Between Imprinting Effects in the Mouse. Genetics. 2004;168:397–413. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coan P, Burton G, Ferguson-Smith A. Imprinted Genes in the Placenta – A Review. Placenta. 2005;26 A:S10–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindot SV, Farin PW, Farin CE, Romano J, Walker S, Long C, Piedrahita JA. Epigenetic and genomic imprinting analysis in nuclear transfer derived Bos gaurus/Bos taurus hybrid fetuses. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:470–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe M, Zhang X, McGinnis L, Biggers J, Li E, Shi Y. Targeted Disruption of Mouse Yin Yang 1 Transcription Factor Results in Peri-Implantation Lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7237–7244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe M, Zhang LF, Xu N, Shi Y, Lee JT. Identification of a Ctcf Cofactor, Yy1, for the X Chromosome Binary Switch. Molecular Cell. 2007;25:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson-Smith A, Moore T, Detmarc J, Lewis A, Hemberger M, Jammes H, Kelsey G, Roberts C, Jones H, Constancia M. Epigenetics and Imprinting of the Trophoblast – A Workshop Report. Placenta. 2006;27 A:S122–S126. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg S, Smith L, Greenfield A, Zernicka-Goetz M. Novel gene expression patterns along the proximo-distal axis of the mouse embryo before gastrulation. BMC Developmental Biology. 2007 doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-8. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-213X/7/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamatani T, Carter M, Sharov A, Ko M. Dynamics of Global Gene Expression Changes during Mouse Preimplantation Development. Developmental Cell. 2004;6:117–131. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata K, Okano M, Lei H, Li E. Dnmt3L cooperates with the Dnmt3 family of de novo DNA methyltransferases to establish maternal imprints in mice. Development. 2002;129:1983–1993. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter B, Helms V, Paulsen M. Tandem repeats in the CpG islands of imprinted genes. Genomics. 2006;88:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Kohda T, Lee J, Ogonuki N, Mochida K, Noguchi Y, Tanemura K, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F, Ogura A. Faithful expression of imprinted genes in cloned mice. Science. 2002;295:297. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5553.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscove N, Barbara M, Gibson M, Modi C, Winegarden N. Representation is faithfully preserved in global cDNA amplified exponentially from sub-picogram quantities of mRNA. Nature Biotechnology. 2002;20:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nbt729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson H, Hayward B, Sheridan E, Bonthron D. A global disorder of imprinting in the human female germ line. Nature. 2002;416:539–542. doi: 10.1038/416539a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama N, Takahashi K, Matsuura T, Sugimura M, Kobayashi T, Moniwa N, Tomita M, Nakayama K. Deficiency in p57Kip2 expression induces preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Okano M, Hata K, Sado T, Tsujimoto N, Li E, Sasaki H. Essential role for de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in paternal and maternal imprinting. Nature. 2004;429:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature02633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko-Ishino T, Kohda T, Ishino F. The Regulation and Biological Significance of Genomic Imprinting in Mammals. J Biochem. 2003;133:699–711. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymenko T, Papp B, Fischle W, Köcher T, Schelder M, Fritsch C, Wild B, Wilm M, Müller J. A Polycomb group protein complex with sequence-specific DNA binding and selective methyl-lysine-binding activities. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:1110–1122. doi: 10.1101/gad.377406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham KE, De la Casa E, Schultz RM. Analysis of mRNA expression during preimplantation development. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;136:315–31. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-065-9:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Oh SP, Okano M, Juttermann R, Goss KA, Jaenisch R, Li E. De novo DNA cytosine methyltransferase activities in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development. 1996;122:3195–3205. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Bench AJ, Vassiliou GS, Fourouclas N, Ferguson-Smith A, Green AR. Imprinting of the human L3MBTL gene, a polycomb family member located in a region of chromosome 20 deleted in human myeloid malignancies. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2004;101:7341–7346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308195101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Bench AJ, Piltz S, Vassiliou G, Baxter EJ, Ferguson-Smith A, Green AR. L3mbtl, the mouse orthologue of the imprinted L3MBTL, displays a complex pattern of alternative splicing and escapes genomic imprinting. Genomics. 2005;86:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann MRW. Imprinting and epigenetics in mouse models and embryogenesis: understanding the requirement for both parental genomes. In: Jorde LB, Little PFR, Dunn MJ, Subramaniam S, editors. Encyclopedia of Genetics, Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons; United Kingdom: 2005. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Solter D. Completion of mouse embryogenesis requires both the maternal and paternal genomes. Cell. 1984;37:179–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi N, Kuroiwa Y, Kohda T, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Kawabe T, Hasegawa H, Barton S, Surani MA, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino S. Identification of the Meg1/Grb10 imprinted gene on mouse proximal chromosome 11, a candidate for the Silver-Russell syndrome gene. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1998;95:1102–1107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Sotomaru Y, Katsuzawa Y, Kono T, Meguro M, Oshimura M, Kawai J, Yomaru Y, Kiyosawa H, Nikaido I, Amanuma H, Hayashizaki Y, Okazaki Y. Asb4, Ata3 and Dcn are novel imprinted genes identified by high throughput screening using RIKEN cDNA microarray. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2002;290:1499–1505. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch S, Djuric U, Mazhar B, Seoud M, Khan R, Kuick R, Bagga R, Kirchesen R, Ao A, Ratti B, Hanash S, Rouleau G, Slim R. Mutations in NALP7 cause recurrent hydatidiform moles and reproductive wastage in humans. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:300–302. doi: 10.1038/ng1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido I, Saito C, Mizuno Y, Meguro M, Bono H, Kadomura M, Kono T, Morris G, Lyons P, Oshimura M, Hayashizaki Y, Okazaki Y. Discovery of Imprinted Transcripts in the Mouse Transcriptome Using Large-Scale Expression Profiling. Genome Res. 2003;13:1402–1409. doi: 10.1101/gr.1055303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Iratxeta C, Palidwor G, Porter CJ, Sanche NA, Huska MR, Suomela BP, Muro EM, Krzyzanowski P, Hughes E, Campbell PA, Rudnicki MA, Andrade MA. Study of stem cell function using microarray experiments. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:1795–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras G, el Kharroubi A, Kozlov S, Escalante-Alcalde A, Hernandez L, Copeland N, Gilbert D, Jenkins N, Stewart C. Zac1 (Lot1), a Potential Tumor Suppressor Gene, and the Gene for ε-Sarcoglycan Are Maternally Imprinted Genes: Identification by a Subtractive Screen of Novel Uniparental Fibroblast Lines. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3308–3315. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3308-3315.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W, Lewis A. Co-evolution of X-chromosome inactivation and imprinting in mammals. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2005;6:403–410. doi: 10.1038/nrg1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf N, Dünzinger U, Brinckmann A, Haaf T, Nürnberg P, Zechner U. Expression profiling of uniparental mouse embryos is inefficient in identifying novel imprinted genes. Genomics. 2006;87:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz R, Menheniott T, Woodfine K, Wood A, Choi J, Oakey R. Chromosome-wide identification of novel imprinted genes using microarrays and uniparental disomies. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:e88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparmann A, van Lohuizen M. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6:846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani MA, Barton S, Norris ML. Nuclear transplantation in the mouse: heritable differences between parental genomes after activation of the embryonic genome. Cell. 1986;45:127–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varmuza S, Mann M, Rogers I. Site of Action of Imprinted Genes Revealed by Phenotypic Analysis of Parthenogenetic Embryos. Dev Genet. 1993;14:239–248. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona R, Mann M, Bartolomei M. Genomic imprinting: intricacies of epigenetic regulation in clusters. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:237–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.092717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana PB, Fossella JA, Matteson P, del Rio T, O'Neill MJ, Tilghman SM. Genetic and epigenetic incompatibilities underlie hybrid dysgenesis in Peromyscus. Nat Genet. 2000;25:120–124. doi: 10.1038/75518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana PB, Guan XJ, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. Genomic imprinting is disrupted in interspecific Peromyscus hybrids. Nat Genet. 1998;20:362–365. doi: 10.1038/3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagschal A, Feil R. Genomic imprinting in the placenta. Cytogenetics and Genome Research. 2006;113:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000090819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F, Baldwin DA, Schultz RM. Transcript profiling during preimplantation mouse development. Dev Biol. 2004;272:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]